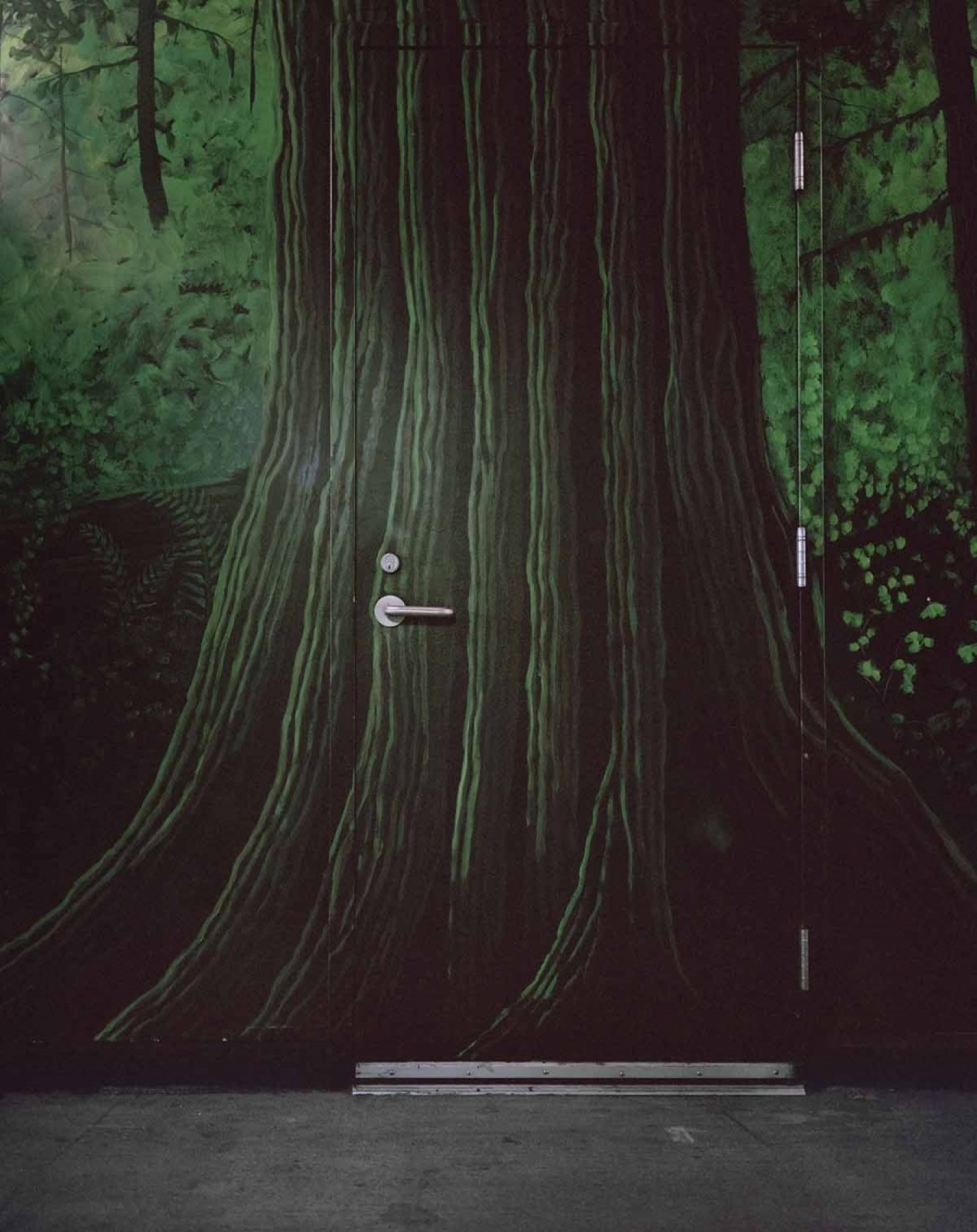

"The Threshold" (2012) by Anna Beeke

The Transom

By Anne Gisleson

Watching a movie or television show with my husband can be vexing. He’s a scenic painter, on the hard labor side of the movie-making equation in Hollywood South, as Louisiana is often called these days, now that tax credits have made our state the number-one filmmaking destination in the country. My husband often gives the industry twelve- or fourteen-hour days and is loath to give it an extra ninety minutes when he gets home. A scenic painter works the surfaces, can make a naked piece of plywood resemble rusty sheet metal, Carrara marble, or speckled linoleum, and creates the illusion of unity between real and fake. While watching a show, his eye immediately goes to the artifice of the set or the location, his brain to the guts and the systems of movie magic, to the bureaucratic insanity that often goes into these productions. Sloppy decision-making at the top means the bottom works weekends. Often it’s someone in an office in L.A. deciding whether or not my husband makes it home for dinner.

Nevertheless, for months we’d been hearing raves about the locally shot HBO series True Detective, written by native son Nic Pizzolatto. I was curious and wanted to watch it with my husband. He relented with a worn-down “sure.” Like millions, we were pretty much instantly seduced by the South Louisiana “psychosphere,” lyrically condensed in the opening credit sequence, where the Handsome Family’s darkly catchy “Far From Any Road” rises and slides along with the images of cane fields and industry, empty playgrounds and hellfire, all overtaking and dissolving into the troubled, desaturated countenances of Matthew McConaughey and Woody Harrelson. Layers and layers of sexy, toxic danger.

One Friday night, just as we were about to settle in for the season finale, I happened to get a text from Pizzolatto’s cousin, a friend of ours in the neighborhood, about the dimensions of a transom he had lying around that we could possibly use on a renovation project. This is a typical transaction in sub-tropic, entropic New Orleans: trading pieces of our old houses as we perpetually work to keep them from falling apart. We were having some French doors installed to open up the back of the house. A rectangular void above them awaited its transom.

Deep into the finale, Rust and Marty pull up to the old oak-sheltered plantation they believe is the home of the serial killer who has eluded them for seventeen years. “Yep, Nine Mile Point, there it is,” my husband says without enthusiasm or surprise. It’s a late-eighteenth-century plantation on the other side of the Mississippi near Bridge City where he’s worked on maybe a dozen sets, including the French production of Kerouac’s On the Road, putting the finishing touches on William Burroughs’s orgone accumulator and making fake pot plants look less fake.

Minutes later Rust has tracked the killer into the mythical “Carcosa,” a labyrinth of ancient tunnels filled with sculpturally lashed-together branches entangled with ragged fetishes and a few artfully mummified victims. Piles of rotting clothes, apparently of the women and children sacrificed there over the decades, are scattered on the ground.

“Huh. That’s where we’re working tomorrow. Fort Macomb.” As Rust stalks toward his cosmic destiny, my husband gives me a brief history of the fort. “It’s out by my folks’ house right before the Chef Menteur Bridge. Part of a string of about forty forts built from North Carolina to the Gulf to protect the coastline after the War of 1812. Really cool.”

“You’re working at Carcosa?”

“Yeah, you should bring the boys out tomorrow.”

The next day, before heading out to Fort Macomb with our two sons, I had some business to take care of. The Pizzolatto cousin’s transom was the wrong dimension. I called our friend Case, a writer and carpenter who was installing the French doors. Among Case’s many tattoos are a hammer drill on one forearm and “Say Yes in 2012” on the other. He writes musicals about lead paint remediation and gentrification, has a McConaughey build, and was lamenting that a back injury was keeping him out of the gym. Our house is about 150 years old, and he had to cut through layers of sheetrock, plaster, lath, and old barge board—wide planks of dismantled barges dragged from the Mississippi a block away and used as building material in the nineteenth century. He said he needed a transom today to finish up the job. I said let’s go find one.

On the ride over to an architectural salvage store in Mid-City, I mentioned we’d finally seen the True Detective finale the night before.

He shook his head in disgust. “Such a disappointment! All the things about character and plot you were willing to forgive because the writing and art directing were so good started popping out. Plus, there are no secrets in South Louisiana, nothing’s hidden. You want to know where the ritual child sacrifices are happening, you just ask someone and they say, yeah, right down the road there at that old fort.”

I agreed. The real horror in Louisiana is that its ills are right there in the open. A show about the serial victimization of women and children would’ve been perfect for this state: we have shameful infant mortality and child poverty rates and a historically damaged education system. Our gender pay gap is appalling, the number of men who kill women in Louisiana is among the highest in the country, and we have the lowest percentage of women elected to public office. This was all coded into that lyrical opening sequence every week: those images of male-dominated power structures—oil refineries, law enforcement, churches—superimposed onto the silhouettes of naked female bodies. Rust and Marty were just part of the problem, damaged by their extreme versions of masculinity.

“Yeah, missed opportunity,” Case said to the windshield. “The show’s wider conspiracy dead-ends with the crazy cracker fucking his sister in an old broke-down plantation. Typical.”

We pulled into the crushed oyster shell parking area in front of the salvage store. Inside were thousands of architectural details from dismembered houses—doors, windows, mantels, columns, cornices, hardware and, yes, transoms of all sizes. Salvage stores make me feel so ambivalent—I’m glad that things are being reused and seeing new life, but I know they’re preserved only through the destruction of what were once homes or old businesses. Was it poverty, greed, or neglect or a more dramatic disaster that would lead one of these transoms to my home? After about fifteen minutes, we found exactly the right size.

Case was sort of wrong about things not being hidden. I’d driven past the ruins of Fort Macomb plenty of times and had never known they were there. Now I know they’re about a hundred yards off Chef Menteur Highway behind a rusted cyclone fence topped with barbed wire and trumpet vine, right before the old drawbridge over Chef Menteur Pass. “Chef Menteur” is French for “Lying Chief,” as the Choctaws called this marshy isthmus of land at the far edge of Orleans Parish. There are a few stories regarding this appellation. One is that the truth-loving Choctaw Indians banished one of their chiefs there for being a big liar; another refers to an early French governor who betrayed the tribe; a third describes the tricky Mississippi River and its adjacent waters, which never follow an honest path.

“It looks like a hobbit hole,” our eight-year-old said when my husband, wilted from a hot weekend workday that had started at 5 a.m., met us at the entrance. Though aboveground, the brick ramparts are overgrown with bright grass, palmettos fanning from the arched entrance, jungly and ornamental.

With the help of a few hurricanes, nature had overtaken Fort Macomb. On the grounds, a curved bastion lined with cannon ports faces Chef Menteur Pass, once a back door entrance to the city from the Gulf through a series of waterways thought to be used by area tribes for thousands of years before they guided the French through it. That outer rampart was separated by a moat, now filled with marsh grass, from another higher one housing barracks and much smaller gun ports. A one-time Confederate outpost, it was severely fire damaged in 1867 and decommissioned by the U.S. military in 1871. You can visit its intact sibling, Fort Pike, about nine miles away, part of that same coastal defense chain of forts, a well-preserved state park with a nearly identical layout to Fort Macomb. Fort Macomb is the present ghost of Fort Pike’s inevitable future.

Unlike Fort Pike, Fort Macomb is not open to the public, but millions have seen it. Not only as Carcosa in True Detective, but in other movies like The Expendables and Devil’s Due. With its high-ceilinged chambers, smaller connecting tunnels, and subterranean feel, the ruins are versatile. They can easily pass as underground passage, fort, cavern, catacomb, dungeon.

The first thing we saw upon entering was CARCOSA carved primitively into the wall, a scarring from the True Detective shoot.

“Obviously, they were not supposed to do that,” my husband said.

“What’s Carcosa?” our teenager asked.

“Just something we saw in a show last night.”

Bringing our kids into Carcosa, the fictional temple of child sacrifice that we’d been mildly creeped out by the night before, felt like part of the casual duplicitousness of parenting—all the omissions, the private jokes, the disparity of experiences that a household accommodates. Twitchy flashbacks of what we’d seen on the screen last night—the human skull and antler altar, Woody Harrelson with an axe in his chest—superimposed themselves onto what I was looking at now.

In the low tunnels, calcium leached out of the mortar between the bricks to make frosty fringes of stalactites. My husband pointed out the difference in the color and quality of mold and mildew on the ceilings and walls in the different chambers, the mottled washes of greens, browns, and ochers. They didn’t match up. They were actually layers of scenic painting from the different movies shot there over the years. What looked to an untrained eye like the fort’s natural aging was actually artificial, manufactured aging. Some of the scenic work was pretty good, he said, some not so great, a little amateurish. The fort was acquiring its own unique type of physical memory, snatches of this process out there for the unknowing world to see on screens everywhere. Fort Macomb’s caretaker had recently shown him a patch of what the fort’s walls, untouched by scenics, would actually look like: a bright chalky white.

We stepped through a giant fissure in a wall between two chambers where the hearth had fallen in, maybe ten layers of brick thick, narrow at the bottom and top and curving out, almost vaginal. Light streamed biblically from vents in the roof into the room, near my husband’s ten-foot ladder and scenic kit: paint brushes, Coke Hudson sprayer, shellac, Chapin sprayers called “pumpies.” All in the service of making fake mildew on a plywood lighting box affixed to the ceiling. My husband explained what he was working on and the boys were quiet. They’re always a little disoriented when I take them to visit their dad at work on a set or location. Already a line of reality has been breached, the line between what Dad does all day and their own days. Once there, reality is tampered with even more—miles of cables, impossible lighting rigs, scissor lifts, ear-searing power tools, carpenters blasting classic rock, ad hoc paint shops, temporary structures within structures, and on the other side of the noise and plywood wall is a replica of the Oval Office or a warlock’s library or a perfectly outfitted morgue.

Through one of the arched entryways to the former parade ground, I saw our friend Ellen, who I’d forgotten was working with my husband that day, standing on an overturned five-gallon bucket of paint, in cut-off shorts, a black tank top, and a thin braid beneath a straw cowboy hat, painting a flat of fake brick paneling.

“Ellen!” I called across the chamber. “You look like the high priestess of a Crackist temple!”

“I am the high priestess of this Crackist temple!” She laughed. Her southern Alabama vowels sometimes stretch so wide that they seem to accommodate another meaning.

On Thursday, the night before we watched the finale, we’d held an informal sort of existential crisis reading group at our house, a monthly event the boys look forward to because they can raid the table for snacks while the adults talk about the condition. Ellen, an artist with an affectionate attachment to her “black mind,” had shared a short story, “The Collector of Cracks,” written in 1927 by the Ukrainian-born writer Sigizmund Krzhizhanovsky. Its characters are burdened by a dark, mystical sort of blurring between physics and metaphysics and the story had actually reminded me of Pizzolatto’s writing in True Detective—Rust’s monologuing about M-Theory and our lives in other dimensions. In the story, a mysterious character in a worn but tidily brushed overcoat, a self-proclaimed “Crackist” living in a “Kingdom of Cracks,” warns against the illusion of wholeness. He is preoccupied with cracks in the physical world but also cracks in the self, “between ‘I’ and ‘I’,” and cracks in time, where he posits we might just exist. He likens his experiments in the “psychophysiology of the visual process” to watching a movie:

Wedged in between instants—when the film, having withdrawn one image from the retina, is advancing so as to produce another—is a split second when everything has been taken from the eye and nothing new is given it. In that split second the eye is before emptiness, but it sees it: Something unseen seems seen.

The Crackist goes on for pages, destabilizing our ideas of perception, time, and existence. He describes an episode in which the sun seems to momentarily go out, and within that cataclysm he loses part of himself, his capacity to love. One passage in particular affected me in a very personal way:

Night, you see, never goes away, even at noon: Torn up into myriads of shadows, it hides right here, in the day; lift up a burdock leaf, and a wisp of night will dart down to the root. Everywhere—in archways, by walls, under leaves—night, torn up into black scraps… . This ontological night never forsakes souls or things. Even for an instant.

In the final scene of True Detective, Marty and Rust, recovering from being knifed and axed by Evil, smoke Camels outside of Lafayette General Hospital, contemplate the night firmament, and engage in some tender Manichean man talk. Rust says he’s come to realize that “there’s just one story, the oldest: light versus dark.” Marty, looking up, observes, “Well, it appears to me that the dark has a lot more territory.” The season’s final line, before the camera tilts up and the night sky fills the screen is Rust’s: “Once there was only dark. You ask me, light’s winning.”

For most of us, of course, light doesn’t win and darkness doesn’t lose. Movies may give us blowout confrontations, but we do the daily skirmishing. Our job seems to be finding true sources of light and acknowledging the scraps of a night that never fully goes away. While the edifying visual complications of the opening credit sequence and much of the season were flattened out for me by the genre-generic ending, I did realize how prescient “Far From Any Road” was as a title song. Like the series, it ends in the stars with selves dissolving into an eternal celestial wind.

“Watch out for snakes,” my husband told the boys as we walked the ruins’ wild overgrown perimeter under the brutal September sun, Chef Menteur Pass glinting just over the ragged rampart. Our adolescent watched the ground cautiously while our eight-year-old chased grasshoppers into the tall grass. The only snaking we saw were the familiar black cables running from generators, the ones we see with frequency around town, part of the infrastructure of fantasy, along with catering and light trucks and massive blue screens that can transform an abandoned suburban parking lot into any locale that can be conjured by the human imagination.

My husband had to get back to work and I kissed him good-bye next to the “honey wagon” parked under an oak tree, a deluxe air-conditioned porta-potty called the P-Mo Grande. “By the way,” I told him, “everything’s squared away with the transom.”

“Mom, why are you still talking about that transom?” my exasperated eight-year-old asked. I was surprised that he’d been paying any attention to me at all, let alone to my home renovation discussions with other adults. I explained to him, again, about the importance of the transom. It’s just a small window over a door, but it seems to make a difference.

Enjoy this story? Subscribe to the Oxford American.