Jim Jackson’s Pork Chop (With Recipe!)

By LD Beghtol

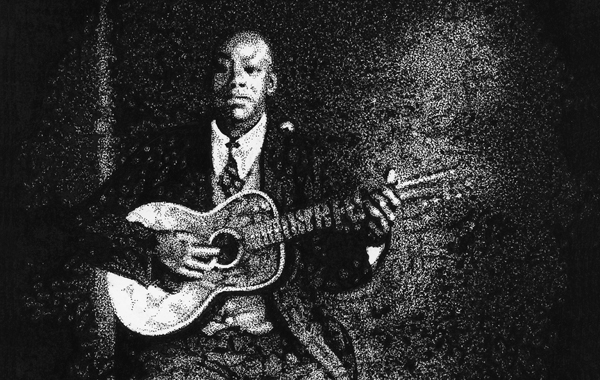

Art by Jim Blanchard.

Food and family, it is said, were the only sanctioned topics of conversation in the Polite South of myth and memory; anything else—politics, race, religion, most aspects of sex—was a sure cure for sanity, if not a shortcut to utter social ruin. Privately, Southerners have always reveled in the antics of their beloved eccentrics, basking in the admixture of mortification and pride that was (and is still) as peculiar a regional institution as the ongoing debate about whether white or yellow cornmeal is tastier or more correct.1 But by tacit consent, the delicious details of who's doing what with/to whom—and why!—were left to be savored discreetly so as not to shock the dear old things at table or incite the young ones to commit more than their share of outrages.

And besides, it was tacky.

But nowadays, the bland homogeneity of media culture has largely cured the South of its public reticence. As contemporary social mores admit a much broader plain for social discourse, we may all indulge our promiscuous curiosity without stooping to “trash TV” or appearing to luxuriate too lustily in the schadenfreude of it all. Everyone has a story, it seems, and is only too happy to overshare in that performative, conspiratorial Southern voice Jessica Mitford once dubbed the “soft scream.” 2

Now I shouldn’t care to be accused of the heedless casting of stones, so I hereby confess that I am not free of the sin of public testifying. Since moving to New York fifteen years ago, I've literally dined out on all the lurid family stories of misdeed and misfortune I can recall. And along the way I've discovered this: The more candid the delivery and truthful the detail, the more likely the listener will think it's all a big con. I tell the one about my sister's shoulder being dislocated by a confused deer, or the dim family friend who hanged himself in the barn when he received a dress in the mail from the Sears catalog instead of the girl he thought he’d ordered, or—scout's honor—my mother’s bloody battle with a bunny that wouldn't stay out of her daylilies, and the inevitable response is: "You guys are such great storytellers! Of course, you’re just making it all up!"

Well, not really. Like M.F.K. Fisher—who was also wrongly accused of never letting facts get in the way of a good story—I am prepared to swear that every word is true. My operatically fucked-up childhood might have been transmuted into authorial gold had it happened a generation or so earlier than it did to me: an alcoholic father with a not-so-secret darkness at heart; a stoic mother with too many children and never enough time or money; illness, heartbreak, and betrayal; violence gleaming just below the surface...and blah blah blah. But industrious types such as Mr. Capote and Ms. Gilchrist mined that vein out long ago, and The Great Santini is a little too close to the Freudian bone for me. Happily, time and other pursuits have dulled my need for such history to be anything other than an amusing anecdote, a tale told—if not by an idiot, then by someone past thinking that suffering ennobles or even informs. One full of sound, certainly. But fury? Not so much.

Oh, and food. Those old ladies were right: What's bred in the bone comes out in the text, especially when many years and even more miles lie between early pleasures and the bleakish present. No latter-day fried chicken is ever so succulent as Grandma’s, no biscuit so cloudlike, no cobbler so ripe with the taste of summers past. Google “pimiento cheese,” and you’ll find a million hits about this gloriously evocative childhood relic. The Southern romance with food is ubiquitous; it exists both as Hee Haw low comedy and the most sacred of personal truths—see Mark Twain's longed-for breakfast in A Tramp Abroad. 3

And like other, more extravagant forms of madness, it taints many a family. My mother, Mae E. Beghtol, née Gibson, was born in 1927 in Pinola, Mississippi, into a big farm family that grew cotton as a cash crop and pretty much everything else for their own delectation: chickens, cattle, and a garden full of vegetable love. At five, my mother and her family moved west to Louisiana, eventually settling in Franklinton. They took their Mississippi—and recipes—with them. Mother speaks fondly of her early life, which, arduous as farm life is, was filled with love and laughter and good food. Her mom never owned a cookbook but daily turned out vast quantities of delicious fare for her ever-expanding brood, even during The Great Depression. They were lucky, Mother says, because they grew almost everything they needed, save for coffee and shoes. She goes into a sort of ecstatic trance describing her father's smokehouse, full of sugar-cured hams, bacon, and sausage slowly aging to perfection in the hickory-scented twilight. Oh, the cracklins! The tomatoes! The lima beans and sweet potatoes!

In due time, Mother finished school (FHS, class of ‘45), attended beauty college in New Orleans, and then worked as a ship-to-shore operator for the phone company, where her clear contralto—happily devoid of that lazy bayou drawl—was put to excellent use. Then marriage to my career-Army father and posts overseas and stateside before settling near Fort Campbell, Kentucky. My troubled dad had fled the dreary Midwest as a teenager to ride the rails. Later, below the Mason-Dixon, he went emphatically native in the studied Southern Gothic/Good Ol' Boy manner.

On to family: As the youngest of seven children, I was largely ignored. This suited, as it left me alone to write and draw, and to delve deep into my parents' collection of old 78s—folk and hillbilly music, Al Jolson, The Carter Family, Jimmie Rodgers, opera, heaps of big band and Tin Pan Alley. Occasionally, I was trotted out to entertain a visiting cousin or impress some adult, which proved useful later. But mostly I read and listened. Summers meant the lake or marathon treks north to my father's wry, alien (read: non-food obsessed) people or down the Natchez Trace to my mother's family. This was sublime: water glimpsed through endless pine trees webbed with Spanish moss, cotton fields, and sugarcane. Everyone sang, and I learned the harmonies. And then we were at Grandma's, where the prime topics of conversation were—well, you guessed it.

Later, in college in Memphis and London, and especially now in the depths of Brooklyn, I too—like the moribund, salivating narrator in Jim Jackson’s hallucinatory recording “I Heard the Voice of a Pork Chop”4—still hear the familiar siren call of long ago, and it is a heavenly thing. Often and often “I longeth; yea, even fainteth...”5 for Mother’s perfectly plain, perfectly perfect stuffed pork chops.

[1] Yellow for me, please. Field corn is for the livestock.

[2] Poison Penmanship: The Gentle Art of Muckraking by Jessica Mitford (Noonday Press, 1988).

[3] A Tramp Abroad by Mark Twain (Chatto & Windus, 1880), Chapter XLIX.

[4] Victor, 1928; recorded at the Memphis Auditorium.

[5] Psalm 84:2, The King James Bible (Cambridge Edition)

My mother’s recipe, given here in her own words:

Stuffed Pork Chops—I usually make six or eight at a time. Preheat your oven to 350 degrees. Use the best center-cut, fresh chops at least one and a half inches thick—or thicker if you can find them. You can use the boneless ones if you prefer. Have your butcher cut a pocket in each from the round side almost to the bone. Sometimes I brown them first in a little fat over high heat in a heavy skillet—cast iron, because everything tastes better cooked in a cast iron skillet. If I'm in a hurry I don't bother, though. Season each side with salt and black pepper as you sear them.

If you have a favorite white bread stuffing, use that;6 I use stale loaf bread or French bread, or both if I have them. Tear or cut it up, and mix that with some crushed crackers—just regular saltines. Soak this mixture in a little water for a minute or so, then squeeze out most of the liquid—you want it to be moist, but not soggy. Sauté some chopped green onions—both the tops and the white part, as much as you like but we always like a good bit—and some chopped white onion in a little butter, along with a stalk of celery sliced very fine (save the leaves for later). Cook just until the onions and celery are soft, but not transparent. Add the bread along with plenty of dried sage—not as much as you'd use in dressing for a turkey—but no other seasoning except the salt and pepper. You want the stuffing to dry out a little, but don't let it get too dry or it won't be worth eating. Take the skillet off the heat and add two beaten eggs and the chopped celery leaves, then mix it well and let cool for maybe five minutes.

Now stuff the chops as full as possible—I use a spoon—and either wrap each one in aluminum foil and close it tight or put in a baking pan and cover with foil. Bake for an hour. If you have extra stuffing you can put some inside each packet, or bake it—covered—in a separate dish. I usually make too much stuffing because everyone likes it.

Serve with fried apples or applesauce and collard or turnip greens. And pepper vinegar, of course.

[Author's Note: I'd add warm blackberry cobbler, which my Dad perversely always ate with lemon sherbet.]

[6] Some people use that Pepperidge Farm mix, but then some people put sugar in their cornbread, too.