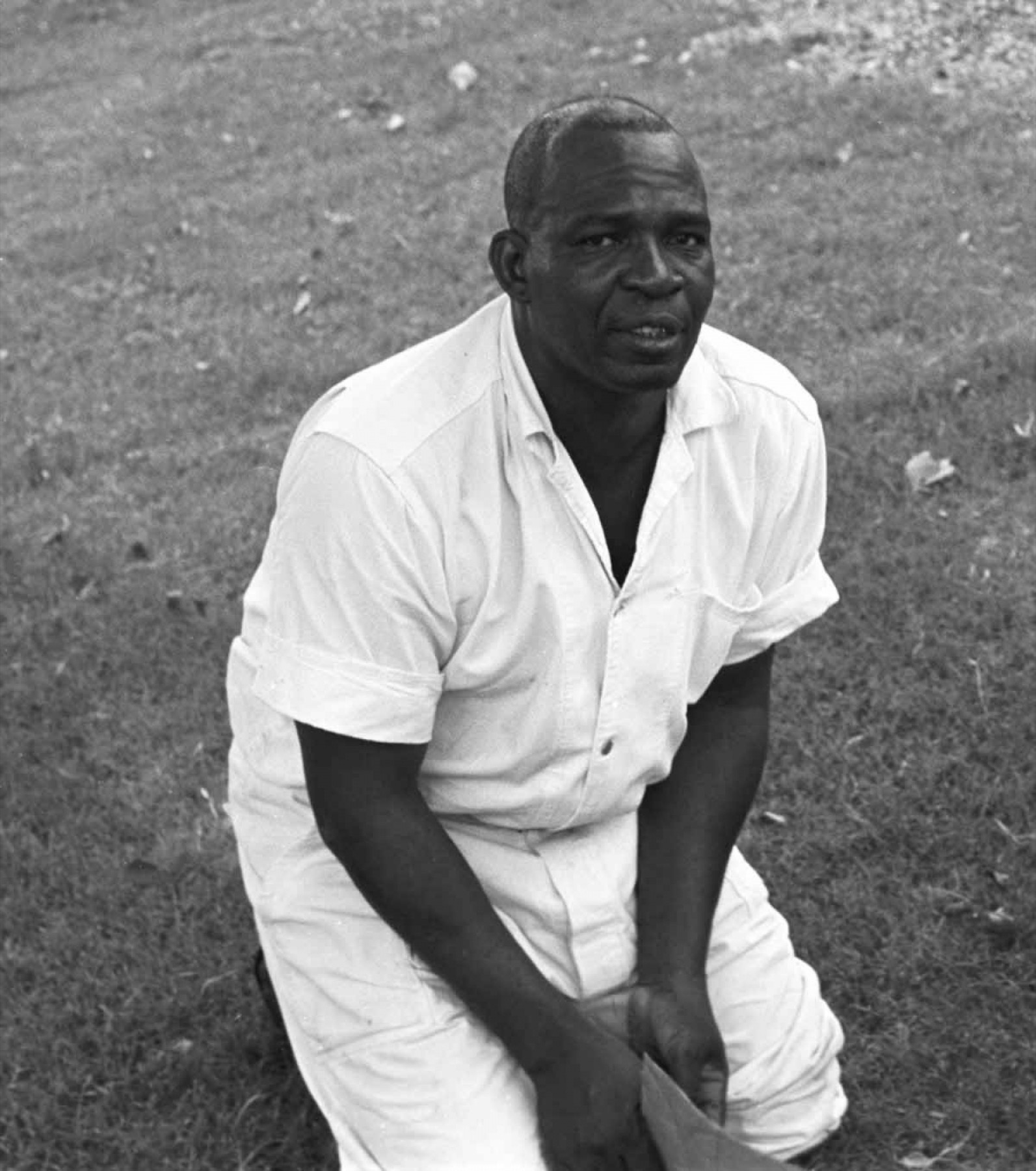

J. B. Smith at Ramsey Prison Farm, Otey, Texas, 1965. Photograph by Bruce Jackson

Sundown Man

By Nathan Salsburg

African-American work songs are long gone. No more will we hear the rowing and boat-pulling chanteys of coastal Georgia and South Carolina or the river-sounding calls aboard packet steamers and the chants of the roustabouts as they unload at Paducah, Memphis, and Greenville. The tie-tamping calls of railroad gandy-dancers, the hollers of the muleskinners behind a plow or atop a levee, have all vanished like Lost John, the hero of one strain of songs, “like a turkey through the corn.”

The songs were singularly affecting, but it’s hard to mourn their extinction. They arose from social, economic, and political arrangements that deserved to die. The iniquities of the turpentine, lumber, and levee camps; the injustices of the sharecropping system. Slavery itself.

The Southern black work songs that men sang while felling timber, chopping logs, clearing bottomland, picking cotton, and building levees thrived before the coming of machines that worked faster and cheaper. When the gangs were displaced, the songs were too. Alan Lomax, who in 1933 first recorded them with his father, John A. Lomax, saw where they went: they “followed group labor into its last retreat, the road gang and the penitentiary.” Southern prison farms recreated the brutality of slave plantations, with blacks toiling in all conditions under the supervision of armed white men on horseback, delivering cheap labor for the bosses that ran them. Work songs flourished there, Lomax continued, “because they were essential to the spiritual as well as the physical survival of the black prisoners.”

Folklorist Bruce Jackson was among the last to record work songs. In 1964 he visited Ramsey State Farm in Rosharon, Texas, where he found both a racial and a generational divide. The Texas Department of Corrections had recently begun to desegregate the work crews. Blacks said the whites didn’t have the rhythm to perform the songs; it's likely that the whites were uninterested in doing so. Older prisoners had long relied on the rhythm to safely “sing down” a tree, or to ensure that teams worked in time so that individual inmates wouldn’t fall behind, risking a beating. But “younger blacks,” Jackson wrote, “saw the songs as holdovers from slavery and Uncle Tom days.”

At Ramsey Unit 2, Jackson met Johnnie B. Smith, prisoner number 130196. A native of Hearne, Texas, Smitty was forty-six years old and on his fourth prison term. His earlier bits had been for “minor charges,” as he called them: two separate burglary convictions and a robbery by assault. This time, however, he was eleven years into a forty-five-year sentence for murdering his wife in a fight in Amarillo. “I got insane jealousy mixed up with love. So many of us do that,” he told Jackson. “Lot of fellas in here today on those same terms.”

In his younger days, Smitty toted lead hoe in a flat-weeding gang and led the work songs. It’s hard to overstate the importance of a good song leader in the penitentiary setting—one needed to be rhythmically, lyrically, and physically reliable, to maintain those songs over interminable hours of hard labor under an unforgiving Texas sun.

But J.B. also sang other songs, different songs—those he’d made up to occupy himself while chopping sugarcane or picking cotton. He referred to them as his “little ol’ songs.” The longest stretched to thirty-three verses, or more than twenty-two recorded minutes. Although Smitty knew and sang a variety of melodies, to an assortment of work songs and sacred pieces, he employed only one tune for his compositions. What changed were the tempo and the ornamentation with which he individualized them. “The Major Special,” “No More Good Time In The World For Me,” “Ever Since I Been A Man Full Grown”—each song Smith charged with its own emotional ambience, as a seasoned preacher intuits the particular colors and atmospheres that should imbue each portion of his service.

In Wake Up Dead Man, his 1972 book on the expressive culture of Ramsey State Farm, Bruce Jackson devoted a chapter to J. B. Smith. Smitty’s nine songs, he wrote, “form so coherent a document and so magnificent a piece of composition that they deserve a section by themselves,” and he presented them in numbered stanzas, like cantos. Drawn from both vernacular and personal sources, and thick with the cast and the argot of the penitentiary, Smith’s songs form an epic of the Southern prison-farm experience. He sings of long-time and lifetime skinners, the sundown man and the danger line, and a procession of riders: a red-eyed captain and squabblin’ boss, a “well-experienced” river ranger with an eagle eye, the dog sergeant and his twelve bloodhounds. He catalogs a small arsenal of Derringers, Winchesters, shotguns, and a German Luger, with concomitant bluster—“If I had my big horse pistol, I’d be dangerous too”—which will be familiar to listeners of other prison song recordings. Occasionally he invokes sites in the system—the Walls Unit at Huntsville, the Central Unit at Sugar Land—but more often he conjures places apart, places free: Oklahoma; Butte, Montana; Pocatello, Idaho; Abilene, where there’s “the cutest little woman you ever seen”; Louisiana, “down with the whippoorwill.” The resort at Hot Springs, Arkansas, appears three times. But most often Smitty is just gone. Long gone.

Smitty called the work songs “time songs,” and time, understandably, was a primary preoccupation. In his 132 published stanzas, he employs the word “never” in 21 instances, “long” in 44. These numbers would be halved if it weren’t for the most remarkable and affecting element of his composition: Smith nearly exclusively employed an ABBA rhyme scheme that turns couplets into quatrains. Narrative is stated and then restated, but often, through inversion of the first lines, from what feels like an emotional or existential remove. The experience is of a closed circle, in which an initial idea comes limping back, occasionally desperate, though most times resigned. It’s a device especially well suited to the circumstances of the prison farm, in which the inmates were worked from “can’t to can’t”—can’t see in the morning until can’t see at night—to rise before dawn the next day and do it all over again. And again.

Been a long lane, buddy, it’s a long lane, buddy, that ain’t got no end,

You may call me lucky but I’m goin’ again.

Whoa, you may call me lucky, hey man, but I’m goin’ again.

It’s a long lane, partner, that don’t have no end.

When he was at Indiana University, Jackson had studied under Robert Fitzgerald, the translator of Homer. They met again later, when they were both at Harvard. Albert Lord was on campus there, too; he had recently published The Singer of Tales, his pioneering investigation of oral tradition and composition, from Homer to the Child ballads. He and Bruce often discussed the work both were doing. It’s tempting to credit the influence of Fitzgerald and Lord, but it’s good fortune alone that led Jackson, at Ramsey State Farm, to an oral composer of a preeminent American vernacular epic: an introspective, soft-spoken habitual criminal prone to understatement, quiet irony, and self-effacing laughter. J. B. Smith’s voice was Homeric (Odysseus meets John Henry), but also Augustinian. His songs were confessions of regret, contrition, impotence, despair. They were also testaments to survival. After all, the purpose of the prison songs was, as Jackson wrote, “making it in Hell.”

Smith was paroled in 1967, a year after his final session with Jackson. A couple years later, a letter from Smitty arrived. He had returned to Amarillo, where he preached for a while, before a parole violation sent him back to prison. That was the last Bruce ever heard of him.

I want some missionary woman, please pray for me,

Don’t pray that I go to heaven, just pray that I go free.

On April 28, Dust-to-Digital will release No More Good Time In The World For Me, a two-CD set of Bruce Jackson's recordings of J.B. Smith, produced by Nathan Salsburg & Steven Lance Ledbetter.

Enjoy this story? Subscribe to the Oxford American.