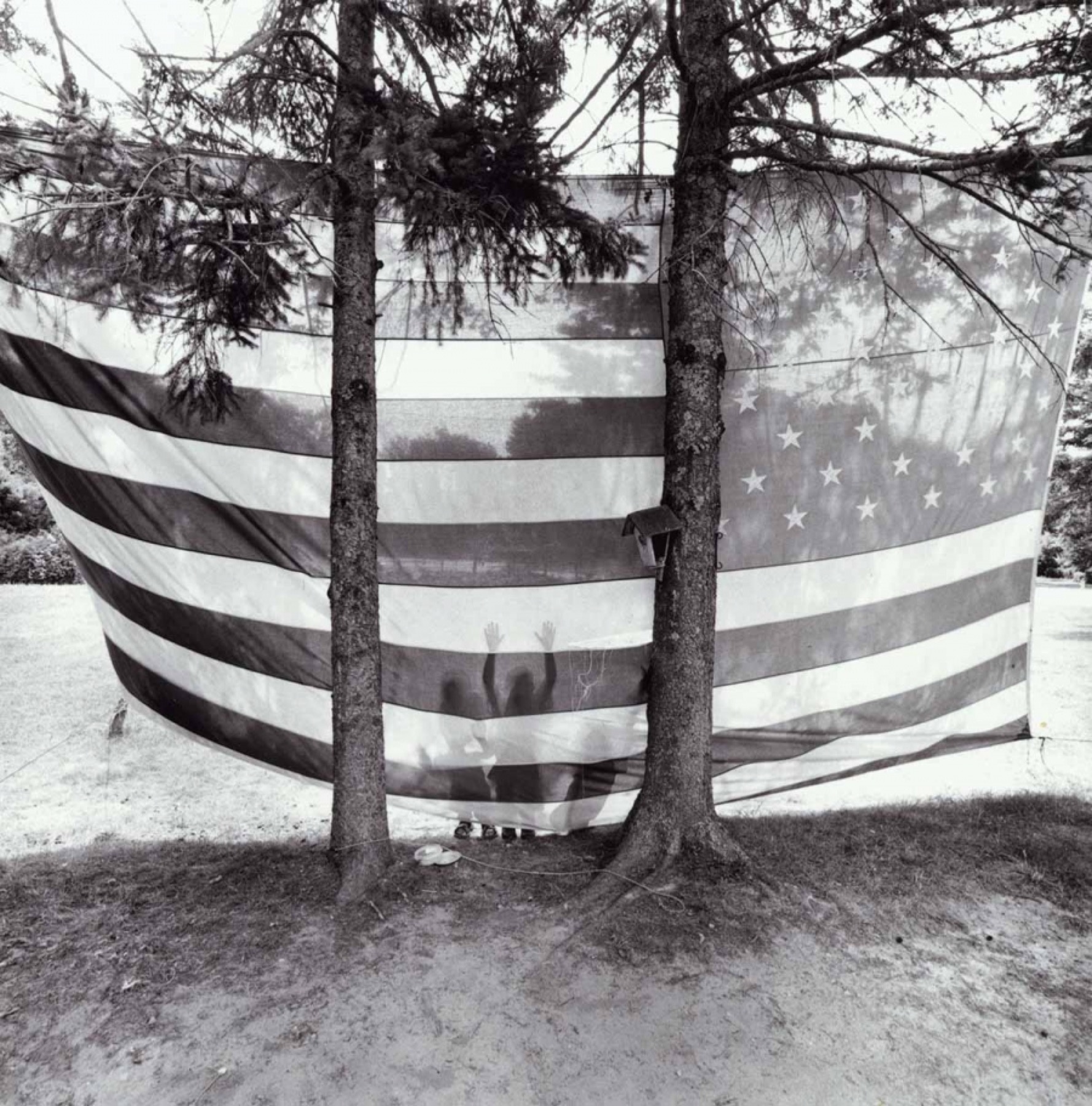

“Cape Cod Flag” © Burk Uzzle

Eff Scott

What makes for a good name?

By Harrison Scott Key

What makes for a good name?

Recently, while visiting a playground, I heard a woman screaming at her daughters. “Peaches!” she said. “Peaches! Where’s Trinity at? Go get your sister!”

Those were pretty good names, I thought. Peaches are a delicious fruit and the Trinity is an impregnable theological notion and both are nouns. There was a little boy in the woman’s lap. Perhaps his name was Danger or Cranberry or Flatbread, which are also nouns. Some people make fun of strange names like these, but I don’t, because this is America, and every name tells a story, and sometimes the story is, “My parents are idiots.”

When I was five, I wanted to change my name, because I was an idiot.

“To what?” Mom said.

“Luke Duke,” I said.

“From TV?”

It was 1981, and the TV show was The Dukes of Hazzard, in which two cousins fight corruption by driving a racist car really fast and shooting flaming arrows at exploding outhouses. Its two protagonists, Bo and Luke, were my heroes.

“You already got a name,” Pop said.

“Harrison Scott Key is very distinguished,” Mom said.

I explained how silly it was that they called me Scott. I didn’t even like writing it, especially in cursive, which was basically like drawing a small duck with brain edema. Nobody else went by a middle name, I explained. Middles were stupid. That’s why you put them in the middle, to hide them, to kill them, to shoot them with a flaming arrow and watch them explode.

I ran out of the room, crying, wondering who I was.

“Why don’t you at least call me by my first name?” I asked Mom, when I was a little older.

“Your father just liked Scott better,” she said.

She wouldn’t say why, but I knew: Harrison was a little too fancy, the lecherous H like the heavy breathing of a sexual predator. It was a good name to have, but you weren’t going to go calling your son that. It was like naming him John Rutherford Smith and calling him Rutherford. Did I want my ass kicked?

Yes, I did—if it meant I could have the same name as the guy who flew the Millennium Falcon. But no. That name would remain frozen in the carbonite of my Social Security card for many years.

S

oon, The Dukes of Hazzard was canceled, and Han Solo got married and settled down, and I turned my attention to more earthly wars, such as the one in 1812, which we studied in U.S. history. “Are you related to him?” my classmates asked, when we saw the name in a textbook.

There it was. Francis Scott Key, so much like the name on my Social Security card.

I could not stop staring at the words on the page, putting my thumb over Francis. I was in a book. My name was in a book.

“Am I related to him?” I asked Mom.

“No,” my mother said. “You were named for other men.”

When you love reading like I loved reading, words didn’t just point to real things in the world. Without words, a table wasn’t anything, a man wasn’t anything, love was nothing. The name didn’t just describe you—it was you.

“Are you related?” people kept asking, in high school.

“It is an odd coincidence,” I said. “But no.”

They’d walk away a little disappointed, having believed they were in the presence of American history, like they’d approached a historic marker only to see, when they got very close, that it was actually a lewd message about oral intercourse.

“That’s a shame,” they’d say.

Yes, it was a shame not to be descended from the great American who’d written a poem about a flag during an unnecessary war that was later set to music and was now used primarily as a metric to assess the quality of our nation’s best pop singers.

And yet, there were coincidences.

I was born on July 5, 1975, exactly 199 years and one day after the signing of the Declaration that led to the war that led to the other war that led to the siege that led to the poem. Every July 4th, I’d hear those stirring notes across a baseball field, through the television, the little bombs bursting in air, and feel a stirring in my bosom. And the next day, I’d have a birthday party, and we’d launch the leftover bottle rockets, and I’d feel proof through the night that perhaps this nation and its song and its author and I had some deeper union.

I wanted to investigate, but how? This was the early Nineties, when computers were primarily used for math and robots. If you’d have told somebody you were “Googling things on the Internet,” they would’ve had you arrested for sexual misconduct. I scanned a few encyclopedias for some evidence of a connection to Francis Scott Key, perhaps a revelation that he’d traveled through Mississippi and made love to many women, but from what I could gather, he seemed more of a family man.

What young artist doesn’t long for a legacy, some affiliation with greatness? I was older now, dating girls from other schools, other cities, meeting people with the annoying habit of being simultaneously attractive, intelligent, and wealthy, young women whose last names gallantly streamed above car dealerships, across billboards.

“Any relation?” somebody would ask, when they saw my name on a form.

“Nope,” I’d say. “Afraid not.”

I was in college now, trying to make a name, a play, a song, something. I’d see my name on a program, a playbill, a poster we’d made up for our band, and I’d think, man, it does sound a lot like the “Star-Spangled Banner” guy. It’d be like if your name were Tammy Zeta-Jones or Larry Ingalls Wilder.

If your name is Randy Bader Ginsburg, you have a duty.

Besides, Mom hadn’t definitively proven we weren’t related to those Keys, had she?

If you ask yourself something enough, you start to remove the question mark.

You start believing it.

The first time I admitted that yes, I was related to Francis Scott Key, it came as a shock, even to me, because, of course, I was lying. While my other college friends experimented with drugs and God, I experimented with genealogy.

Soon, I found myself trying to learn to pretend to be a writer and was surrounded by other pretend writers. “So you must be related to F. Scott Fitzgerald, too,” one of those pretend writers said. “Since his full name was Francis Scott Key Fitzgerald and all. Surely you knew that.”

“Yes, I knew that.”

Of course I did not know that.

“How great for you, to have such a literary lineage,” people said.

And it was great, and it was not great, because now these people were way more excited.

“Tell everybody who you’re related to!” friends would say, when introducing me to their other friends. I’d play it down, it was nothing, really, please, sit down, you’re drawing a crowd, which I’d always wanted, but not in this way, not like this.

And yet, it felt great.

What a tonic this was for the young artist! And it was easy to believe. Like Francis, I was a failed amateur Southern poet and had seen many interesting things while on boats. What he saw were the broad stripes and bright stars over Fort McHenry, while I’d seen hot girls in bikinis who would not speak to me. We had so much in common.

“H

arrison Scott Key,” one of my new professors said, after I ended up in graduate school. “That’s a great name for a writer. Are you a writer?”

“I’d like to be.”

“What shall I call you? Harrison or Scott?”

“Harrison,” I said.

And just like that, I was Harrison.

Sometimes, family members and friends from back home gave me a hard time about the name change, and I reminded them: I was a writer, an artist. There was a precedent for this.

I reminded them of Abram, who became Abraham.

And of Saul, who became Paul.

And of Lil Bow Wow, who became normal-size Bow Wow.

Now that I was Harrison, nobody much asked about Francis. But I still hadn’t proven it wasn’t true. It was the twenty-first century now: I had ways to find out, storehouses of dates and names, labyrinths peopled by the dead, and I knew: I must go to these electronic cemeteries, these websites, and find out.

So I did.

But it was confusing, so I went to other websites, to look at pictures of squirrels doing funny things, like opening tiny mailboxes with their tiny squirrel hands. Soon, I’d forget what I’d intended to do, which was good, because they said the truth would set you free—but would it? Seemed like it could lock you up and throw away the only Key you’d ever wanted to be.

B

y my early thirties, I was married and living in a small Mississippi town. I struck up a friendship with our pastor, a historian by education, and one of the kindest, most earnest men I’ve ever met. I’ll call him Marcus. The first time we met, his eyes lit up when he heard my name.

“Any relation to the great Francis Scott Key?” he said. I’d never seen anyone so excited.

“Yes, I think. Maybe.”

I’d forgotten that I’d decided to stop lying about this.

“How absolutely grand!” he said, regaling me with tales of history surrounding Key, and then acted ashamed, for of course I knew these tales already, our being related and all.

A few months later, Marcus baptized our first daughter.

“What is your daughter’s name?” Marcus asked, in front of the church, and I said her name aloud, and he wet the baby’s head, and the baby cried, and the people smiled, and then we celebrated God’s covenantal love by eating a suckling pig. We ate and laughed, my family and my wife’s, these two families who’d given us a name for the baby. When I said her name aloud by the old marble font and Marcus repeated it, I thought, yes, this is a good name, it tells a story to her about her people.

At dinner, Marcus presented me with a gift, a book. Francis Scott Key: Life and Times by Edward S. Delaplaine.

My heart fell.

“Since you’re a descendant of such a great man,” he said.

“What great man?” my mother said.

“It’s a biography of your son’s namesake, Francis Scott Key,” Marcus said.

“Oh, that’s silly,” Mom said. “We are not related to Francis Scott Key.”

I stood up to go get the baby, and asked Mom to join me, so I could drown her in a nearby river. Marcus looked confused, and dinner was over, and everybody left.

I’d been found out.

L

ater, I turned on the computer. Even if I wasn’t a direct descendant, surely we shared a common progenitor, a Master Key.

What I found was a Sampson Key and a Fonzie Key and a Coffee Key, tales of strawberry farmers and the Spanish-American War and boats that had launched in Liverpool and landed in Mobile, men and women who carried babies and guns and plows, from the Old World to the New, up the James River, up the Mississippi, a thousand scattered stars. I looked for a Francis Scott Key somewhere in the galaxy of men who gave me a name, and I didn’t find one, nor an F. Scott, nor even a poet or a diplomat or celebrated alcoholic.

And then, I found a picture of a headstone.

Henry Harrison Scott, born near Holly Springs, Mississippi, on July 5, 1861.

I didn’t have to call my mother to know. This was the man whose name they’d given me, my great-great-grandfather. And now I knew why. We shared a birthday.

Later, my parents confirmed it.

I was ashamed. I had found no writers, no men whose patrician faces and clean chins were in encyclopedias. All I’d found were constables, soldiers, fiddlers, masons, trappers, preachers, fathers who didn’t deserve to be forgotten because a son thought he needed to invent a lineage.

Ten years later, I wrote a book about my family, mostly so my children wouldn’t have to invent a history, when the real one was so strange, so funny. When a large box arrived filled with many copies of this book, I opened it and let my daughters see what was inside.

“That’s your name!” one of them said, holding the book. She was a reader too, a believer in words. Her eyes grew big as her finger ran across the name. “Is that really you?”

Occasionally, I still wondered about the man whose name I had, and if we shared more in common than a birthday.

“Do we know anything else about him?” I asked my mother.

“A little,” she said. “Some things your grandmother told us.”

“Like what?”

“This is interesting,” she said. “Henry Harrison Scott was not his real name.”

“What?” I said. “Why?”

“Nobody knows.”

My heart shot toward the sky. I was dizzy. I saw stars. I saw stories. Maybe he was running from the law, or a jealous husband, or maybe he’d stolen something, a horse, a heart, a baby. When had he done it? Was he eighteen years old, young, dreaming of something his name could help him do, like write songs for the fiddle, or muckrake for the early broadsheets of Memphis, or leave the war-torn lands of his natal home and become the next Gilbert or Sullivan?

“Maybe he just wanted a new one,” Mom said.

Here was the truth, finally. I was named for a man with a name I will never know. Maybe it was a bad name, like Steadfast Peaches or Perseverance Trinity or Cranberry Flatbread.

Occasionally, people still ask about my name, such as a woman on the phone recently, a representative of our local Daughters of the American Revolution, who invited me to speak at their Independence Day event. “We’d like you to talk about your famous ancestor,” she said. “You are related, aren’t you?”

How glorious, to stand on a stage on this day that has always compelled me to think about my name and pull a fast one on the old ladies who deify old names, who so badly want to celebrate their tenuous parentage that they are willing to believe a lie about who I am so that I will stand with them in one of Savannah’s old colonial cemeteries on the Fourth of July and congratulate us all on being affiliated with greatness.

They seem like nice people, and it could be a great speech, very patriotic. I could make them cry. Tears of pride. Tears of American history.

But I declined.

It would be so hot. And I come from much more interesting people.

Enjoy this story? Subscribe to the Oxford American.