The House of Myth

By C. Morgan Babst

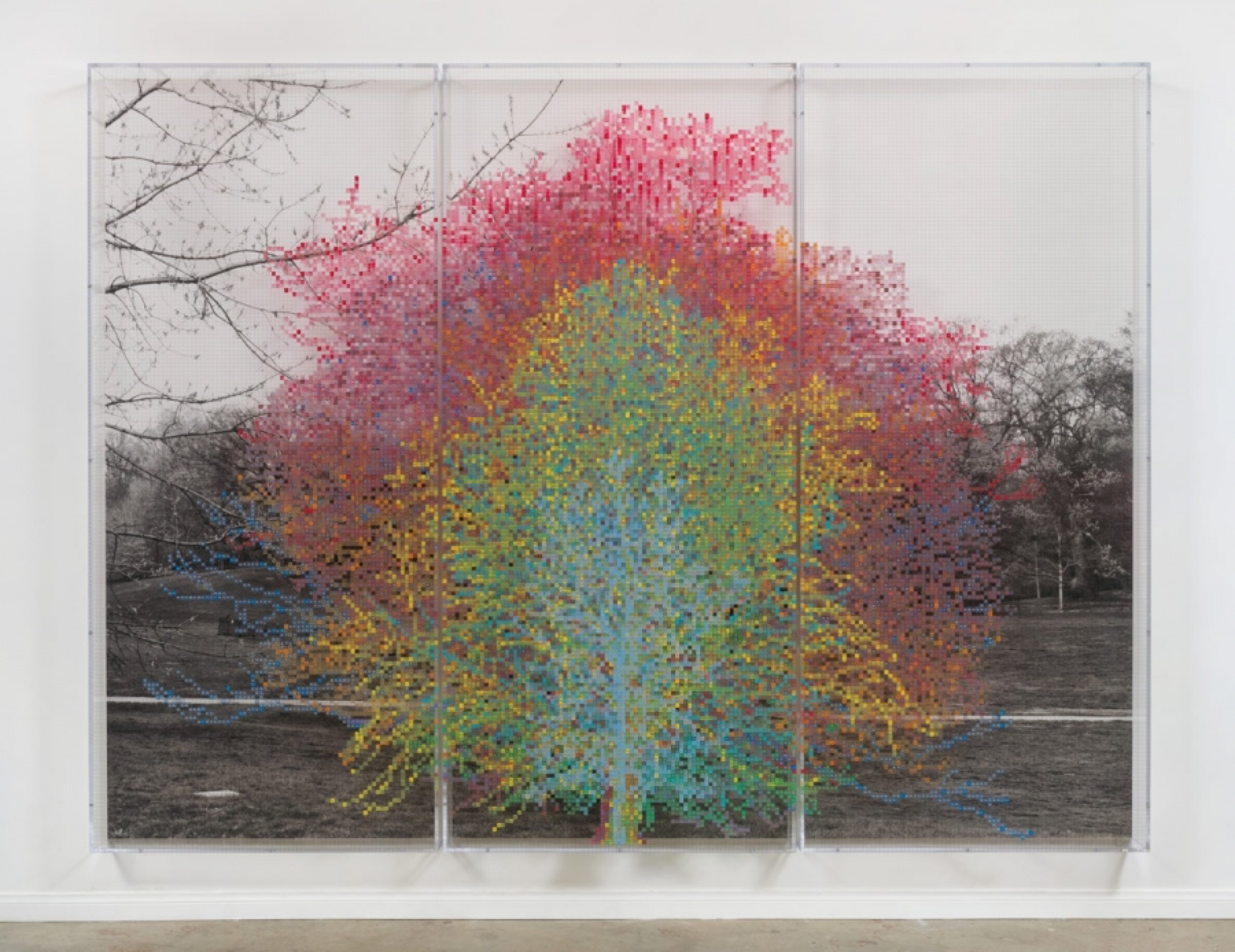

“Numbers and Trees: Central Park Series I: Tree #9, Pamela” (2016), by Charles Gaines. Photographed by Robert Wedemeyer. Courtesy of the artist and Hauser & Wirth

On the architecture of white supremacy

T

he house my grandparents built was one story, brick. It sat modestly on its suburban lot, a stone’s throw from New Orleans, its front door shaded by a small portico and hidden from the street by a young live oak. Inside, beyond the foyer, a paneled great room was lit by a wall of windows. Through them, every Sunday, we watched my grandfather circle the kidney-shaped pool in his Speedo, fishing for leaves. The house always smelled like cooking. Snapping turtle turned to sherried soup. The ducks my uncle hunted became gumbo. In the spring, there were crawfish boils under the carport’s overhang, Southern spaghetti after baptisms. Wakes were held in the formal rooms blanketed in deep white carpet, the sideboard heavy with lemon squares, rum cake, macaroons. On the parlor upright, my aunt, laughing, interminably played “The Spinning Song.”

But inside this house was another house. Hidden in the private corridor that led from master bedroom to guest, beside the powder room door, was a photograph, in black and white, of Rienzi, the Thibodaux mansion where my grandmother was born. It was a house divided into thirds: dark roof, veranda, floodable ground floor. Eight columns broke the façade into seven bays. From gallery to grass ran two sinuous stairs, one flight for ladies, I was told, one for men. It was the stairs that fascinated me—the idea of belles descending in wide crinolines. The building, otherwise, was unremarkable, flanked by oaks and painted white, as plantation houses invariably are.

I liked that house. I stared at it a lot when I was hiding from my cousins or the old ladies, with their butterscotch and damp hankies. I liked the story I was told about it: that the house was built for Empress Josephine, la reine of Rienzi, on speculation that she would come to French Louisiana upon her exile following the Napoleonic Wars. This story was less than legend, the truth of it so tenuous that my family never bothered to check our facts—we had the wrong queen, wrong etymology, wrong colonial power, wrong timeline. The story’s wrongness, though, was a powerful opiate, the fuel for further fantasies. I imagined my grandmother’s birth in the half-tester bed where a queen had once slept, imagined her brushing her long red hair—one hundred strokes a night. I imagined her walking along a long, dusty road to the schoolhouse where she taught or leaning against the railing of the veranda, looking out over vast, empty fields of cane. The fields, when I imagined them, were always empty. The people who’d worked them did not appear in the story we told, because really it was a myth, built to do what myths do: mask the truth.

If you’re an American, you know this house, too: Scarlett runs in white ruffles from the awkward bulk of Tara. Django rides postilion up the red road toward Evergreen. As a teenager, maybe you got off a bus with your gaggle of classmates, tried to keep it together as a hoop-skirted guide led you on the rounds: dovecote, widow’s walk, cone of sugar. Maybe, as a young man, you drank bourbon beneath Edison-lit oaks, cringed at the cotton in the bride’s bouquet. Maybe this house appears in the bottom drawer of your bathroom vanity, printed on the handfuls of soaps that you stuffed at some point in a suitcase. Or maybe you’ve avoided this house, country-driving, hunting boudin. Maybe, slowed behind a bridal limousine, you averted your gaze as the white pickets flashed, grumbled something about how no one would host a wedding at Auschwitz.

For a long time, a book by surrealist photographer Clarence John Laughlin lay on my mother’s coffee table. Full of images of plantation houses—Rienzi among them—this book, Ghosts Along the Mississippi, seemed seductive to me, occult. Like William Mumler, the charlatan photographer who used double exposure to produce pictures of “spirits”—ostensibly the ghosts of loved ones his clients had lost during the Civil War—Laughlin exposed house upon house, collaged colonnade within colonnade. Trying to create an “elegy” for plantation culture, Laughlin shot the houses from low, close vantage, so that their columns stand against clouds that rise “like the smoke of destruction.” Looking at these buildings through the lens of the “mythos of plantation culture,” he wrote, characteristically maudlin,

we often sense . . . the swish of a silken invisible dress on stairs once dustless, the fragrance of an unseen blossom of other years, the wraith momentarily given form in a begrimed mirror. These wordless perceptions can be due only, it seems, to something still retained in these walls; something crystallized from the energy of human emotion and the activities of human nerves. And, perhaps, it is because of this nameless life of memory and desire and, correlatively, because of a superior power of suggestion, that for those who are sensitive, the ruined houses have a fascination far exceeding that of the intact, and inhabited structures.

Indeed, looking at these pictures as a child, I thought I was looking at something ancient, something over. Gutted by fire, eroded by rain, reduced to a colonnade choked by vines (Laughlin called this one “Enigma”), these places seemed safe to romanticize, like the ruins of ancient Rome. Slavery was over, I thought—white supremacy was over—and these houses were beautiful in their destruction, emblems of decontextualized despair.

What it took me a long time to grasp is that beauty is often a con—a lure, an advertisement, and a blind. Think of Stalin’s symmetrical Seven Sisters, the Cathedral of Light shining above the Zeppelin Tribune during Nazi rallies. Think of Vivien Leigh’s face, that dress made of drapes.

In his essay “The Villa as Paradigm,” architectural historian James Ackerman explores the propagandic power of the country estate, establishing plantation houses as part of the two-thousand-year-old lineage of the villa. In its opulence, a villa is the antithesis of a utilitarian farmhouse—a sort of bourgeois folly built to cocoon its wealthy inhabitants in pastoral pleasures provided by the labor of others. As a purpose-built Arcadia, “the villa accommodates a fantasy impervious to reality,” writes Ackerman. “It is a myth . . . through which, over the course of millennia, persons whose position of privilege is rooted in urban commerce . . . have been able to expropriate rural land often requiring the care of a laboring class or of slaves for the realization of the myth.” Constructing that myth is important, as the myth itself buttresses the wealthy planter’s position, projecting an image of graciousness and beauty that partially occludes the means by which that “graciousness” was achieved.

Just as the architects of Renaissance cathedrals used perspective and volume to concretize the omniscience and sovereignty of God, so Southern planters constructed an idyll in which their supremacy and moral right to rule were as solid as wood and mortar, building physical and psychic structures that literally and figuratively obscured the theft of millions of human lives in service to their construction and maintenance. The myths embodied by these buildings were so enthralling that the Civil War diarist Mary Boykin Chesnut could complain about having to interact with the people she enslaved, so seductive that more than a century later, a black-and-white photograph of a house could cause me, as a child, to become blinded to the real lives of the people who had lived there.

In her Louisiana Project, Carrie Mae Weems photographs herself alone along the Mississippi River. In long sprigged cotton, she moves between columns, toward the levee. She dances, her brown feet bare on the blond parlor floor, her arms moving about her with sinuous freedom. She sits in a window and gazes out at the cane, sits in the grass and gazes up at the white house. It is a house divided into thirds: dark roof, veranda, floodable ground floor. Eight columns break the house into seven bays.

In these photographs, Weems is almost always gazing, her back to the viewer, her body a lens through which we re-see what she sees: The house. The river. The cane. A refinery. A graveyard. A housing project: its metal pillars and narrow porches reverberate against the verandas and columns of the plantation. These are blunt juxtapositions—the living black body in the dying white house, the myth of past grandeur against the reality of persisting poverty—but their bluntness is necessary to provide a jolt sufficient to knock the scales from eyes used to seeing “Southern charm” when they look at sites of genocide.

I was home with my two-year-old daughter when the Ferguson Uprising began in 2014, and like many Americans watching the news that summer, I experienced a shift in perspective that was almost physical, as if someone had taken me by the shoulders and turned me around: I saw, suddenly, how these myths of the South had worked upon me, trained me into mistaking who was dangerous in America. As I educated myself, I became determined not to pass along this mythology of whiteness to my daughter, but rather to tell her the truth, as far as I could grasp it. This truth includes the plantations that are part of America’s past and our own.

The first plantation she visited, at four, was Whitney, where she became enthralled by the bronze statues of enslaved boys and girls that linger in the vestibule of its chapel, and for the better part of a year she asked me repeatedly to explain slavery to her, its economics and cruelties, its baffling relationship to race. Then, last spring, we visited Madewood, a massive Greek Revival on Bayou Lafourche where my brother and I spent childhood New Year’s Eves flaring sparklers into the soup-thick outer fog. On our way, my brother and my daughter sat in the backseat, watching Beyoncé’s Lemonade. Inspired, in part, by Weems’s photographs, Beyoncé filmed much of the latter half of her visual album at Madewood: Serena Williams drifts down the curving stairs to where Beyoncé herself lounges, a bodacious queen in a baroque chair. Blue Ivy scampers down the staircase, bounces on one of the beds. The mothers of Trayvon Martin, a seventeen-year-old high school student shot to death by a neighborhood watchman in Sanford, Florida; Michael Brown, an eighteen-year-old music lover shot to death by a police officer in Ferguson, Missouri; Eric Garner, a forty-three-year-old father choked to death by police officers in Staten Island, New York; and Oscar Grant, a twenty-three-year-old father shot to death by a transportation official in Oakland, California, sit along the hall, holding pictures of their sons. Around the long dining table a Mardi Gras Indian queen walks, shaking her tambourine as if to cleanse the air.

When we arrived, the house manager told us how people had been flying in from all over the country to see the Beyoncé chair, booking overnight stays to sit in the Beyoncé chair, then leaving before dinner. My daughter stood in front of it, but her back was turned, her body tense, as she looked down the high hall. “I don’t understand,” she said, wrinkling her nose. “The bad white people lived in this beautiful house?”

Let us look again, now, at this beautiful house, read it this time as a series of universally legible signs for white supremacy. You arrive on horseback and wait outside a gate—the first of several barriers, both physical and human, that must be passed through to reach the master—and enter onto a private road that takes you through a cathedral-like apse of oaks, arranged to express the planter’s dominion over the natural world. From this road, you do not see the functional buildings—kitchen, smithy, stables—nor the quarters for the people the planter enslaves; those are small, unpainted, off to the side. The planter’s house stands alone at the end of this archway of boughs, a telos and a temple. Great white columns rise two stories from their plinths, supporting a pediment that drags its tip against the sky. It looks for all the world like a Roman temple. And who lives in temples but the gods?

“The villa inevitably expresses the mythology that causes it to be built,” Ackerman writes,

the attraction to nature . . . ; the prerogatives of privilege and power; and national, regional or class pride. The signifiers range from the siting and form of the building(s) as a whole to individual details and characteristics. Since signs and symbols convey meaning only to those who know what they signify, they are usually chosen from past architectural usage.

The builders of plantation houses drew deeply from the Roman architectural tradition, especially in the later phases, as fears of abolition made them insecure in their positions. As architectural historian Catherine W. Bishir writes, “Classicism universally reiterated the ideal of a venerable and stable hierarchy,” and so the classical ideals of rationality, order, symmetry were expressed in the architecture of the planters’ houses.

While the idea that the United States was created in the image of ancient Rome had been popular across America since its founding, the craze for all things classical grew even stronger in the South as its racist power structure came under threat after the war of 1812. “Graeco-Roman precedent, once deployed to visualize a utopian future,” writes art historian Christopher Johns, “was reconceptualized as a justification for the status quo.” That the inventors of democracy had enslaved people to till their soil provided the planters with moral solace. “Julius Caesar sold at one time fifty thousand slaves,” remarked South Carolina senator William Smith to Congress, “yet Caesar was never held to be a cruel or barbarous man.”

This defense in many ways was tautological. Caesar could not be a metonym for both Rome and the barbarians at its gate, and the Southern planters took great pains to style themselves as Caesar—or, more often, Cincinnatus, the legendary Roman ruler who twice retired to his farm. (In 1815, North Carolina, the poorest state in the Union, spent nearly ten percent of its public revenues to commission the Italian sculptor Antonio Canova to carve a George Washington in toga and curls.)

Aspiring to the Romans’ imperial legitimacy, Southern landowners arranged their plantations along the lines of Roman latifundia, their layout carefully reproducing, as Foucault would write, “a pyramid of power,” with the planter at its top. In building their houses, they hewed closely to classical forms, adding dentil molding and those massive, fluted columns that became almost synonymous with the late plantation form.

Somewhere in my parents’ attic is the poster I markered in sixth grade of the Classical Orders—Doric, Ionic, Corinthian—and the high school paper I wrote on the Greek Revival. The columns were made of brick, I wrote, made of clay, made in kilns on the land. Laid and mortared, they were covered in plaster made of lime, made of river sand.

The passive voice was always used—read any historical marker—unless we were talking about the cotton merchant who paid for the structure, the architect who designed it. Among the preservationists I knew, old houses were loved, cared for, celebrated, even mourned. I love them too and live in one now, built in 1876—I’ve hired electricians to rewire it and expert masons to custom mix the mortar needed to repoint its old-brick piers. On the pane of one of its front windows, made of pre-industrial rumpled glass, someone at some point scratched the name Lusk in shaky cursive. I stand up from my writing sometimes to touch the letters and wonder who Lusk was: a glazer or a servant or an owner of the house, an adult or a child, the writer of the name or someone she lost or loved.

At some point I realized that the intense focus I’d learned to train on houses often served to hide the humans who made them: the men who built the kilns, made the bricks, mixed the mortar, laid the bricks. The men who made the men make, mix, lay; the whip in that man’s hand. Even the word plantation, from plantare, to plant, is a deactivation: a verb made subjectless, amoral and sedate.

I was an adult before I read the short story “Po’ Sandy” by Charles Chesnutt, the first black writer to be published in the Atlantic Monthly, in which an enslaved man is transformed into a tree, then felled, sawn into boards, and used to build the master a new kitchen. It was only in reading an essay on Chesnutt by literary scholar William Gleason that I learned that such new kitchens were built external to the houses not just for fear of fire, as I’d been told, but as part of a general push to separate the master’s domain from the labor of the enslaved. As architectural historian John Michael Vlach writes, a previous routine of “day-to-day intimacy was progressively replaced by a stricter regimen of racial segregation that was expressed by greater physical separation. The detached kitchen was an important emblem of hardening social boundaries and the evolving society created by slaveholders that increasingly demanded clearer definitions of status, position, and authority.” I began to notice how plantation houses swallowed the doorways to sculleries, how the service wings were rendered nearly invisible by the white bulk of the big house. How, at the plantations I’d visited, the slaves’ quarters were almost always gone. Standing at the base of the Erechtheion in Athens and staring at the porch of the Caryatids, I made a further connection: columns are people, too.

In the first century, Vitruvius explained the origins of caryatids, “those draped matronal figures” that stand in the place of columns at the treasuries of Delphi and at the Acropolis: women turned to stone, bodies used for buildings. In De Architectura, he writes:

Carya, a city of Peloponnesus, joined the Persians in their war against the Greeks. . . . Carya was, in consequence, taken and destroyed, its male population extinguished, and its matrons carried into slavery. That these circumstances might be better remembered, and the nature of the triumph perpetuated, the victors represented them draped, and apparently suffering under the burthen with which they were loaded, to expiate the crime of their native city. Thus, in their edifices, did the ancient architects, by the use of these statues, hand down to posterity a memorial.

Of course, not every column is a caryatid; yet, some dimensional correspondence always carries between pillar and person. Certainly, columns are always a symbol of power. Columns flanked the auction block at the old St. Louis Hotel, where the largest slave auctions in New Orleans were held. Columns make a cordon in front of the courts. Guarding the planter’s door, columns the girth of four men stand, wearing dresses of fluted plaster.

In their use on plantations’ verandas, columns serve an additional purpose: one of occlusion and erasure. For a long time, the veranda baffled architectural scholars searching for its origins. How, they wondered, had this structure appeared with such ubiquity and synchronicity across a region so diversely peopled with Europeans? It wasn’t until 1980 that historian Jay Edwards traced its origins to Africa. When this paper was ignored, he had to publish on the subject for a second time.

It comes as little surprise that Edwards had a hard time making himself heard. Denying the African influence on the American landscape is standard practice. “The impact of African architectural concepts has ironically been disguised because their influence has been so widespread,” writes Vlach. “They have been invisible because they are so obvious.” Just as the physical presence of black citizens in America was shunted to back doors and servants’ entrances, the back of the bus and the colored beach, so were the architectural contributions of Africans effaced from the history of American architecture. Blackness was rendered invisible in the American landscape to enforce the dominance of whites. This whitewashing was, as architect Mario Gooden writes, “a historical and social exorcism” that white Americans effected in an attempt to purge our demons while removing from history the real black men and women who built much of our landscape—from plantation houses to shotgun shacks to the U.S. Capitol and the White House. “Because of this joint history,” Gooden writes, “white stereotypes of [blacks’ contributions] have been constructed to deny to themselves their own blurred blackness.”

By appending classical columns—a highly legible symbol of Western civilization and power—to the veranda, Southern planters effectively obscured the blackness of the plantation house’s most distinctly African structure, a structure so well suited to the climate and inhabitants of the region that it has become almost a metonym for Southern life. In so doing, the white planters portrayed themselves as the sole architects of “civilization”—while their dark-skinned chattel were barbarians whose freedom might well bring about that civilization’s end.

For a time, of course, it did: war came, Sherman’s troops burned Atlanta, and countless plantation houses were pillaged or destroyed—“ravaged” to use Laughlin’s word. But, after a brief period during which, to judge by the political cartoons of the time, bearded Reconstruction went about sacrificing toga-clad youths on the “Altar of Radicalism” while the Southern states as Vestal Virgins watched, all those little wounded Caesars went about trying to get Rome back. Some are still trying.

Since I was a child, I’ve learned that the house my grandmother grew up in was not named for la reine Josephine, nor for the Spanish queen Maria Luisa, actual subject of the legend. “Rienzi” has nothing to do with queens at all, in fact, but was the nickname of Cola di Rienzo, a sort of trecento Italian Trump. Picture a Giotto youth in a red brimless cap embroidered RENDI ROMA GRANDE ANCORA. That was our guy.

Captivated as a boy by the imperial history of his native Rome, Rienzi grew into a man with the ambition to try to return the city to its former glory. On Whit-Sunday, 1347, he dressed in full armor and led a procession to the Capitoline Hill, where he gave a rousing speech on “the servitude and redemption of Rome” and his plan, personally, to redeem it. For less than a year, Rienzi ruled. He cleared the streets of barbarians—not humanely—and brought about a symbolic unification of Italy, but eventually he was forced to flee. When, after a period of exile, Rienzi tried to regain power, he was murdered by a mob. The Romans dragged his body through the streets of the Eternal City, then hung it, upside down, so that it could be stoned by passersby. Two days later, they cut down what remained of his corpse and burned it on the tomb of Augustus.

My great-great-grandfather, Emile Morvant, bought the house named after Rienzi together with his business partner, J. B. Levert, in 1896. By 1922, the Morvant family was deeply in debt, and the house passed into the Leverts’ exclusive control. Until just recently, those few details were all I knew about Emile Morvant or the plantation, besides that legend about the queen. I have never been inside. I remember seeing the house only once, when my father and I took a detour off the I-10 on some day trip to Baton Rouge and slipped over the Sunshine Bridge toward Thibodaux. He parked the car on the shoulder of the road, and we stepped out and stood for a while at the white, swaybacked gate. At the end of a short drive, the house stood, its double stairs sweeping down toward the grass, just like in the picture. Beyond it, bulldozers moved across the cane fields, clearing the land for subdivision.

I didn’t realize then that what I was seeing was the end of the plantation economy; despite the war and Reconstruction and repeated efforts by labor organizers, conditions for those who worked the cane fields remained almost unaltered until the 1980s. In those years, all across the South, bulldozers like the ones moving earth beyond Rienzi were plowing over the gravesites of the men and women who had worked those fields, enslaved or underpaid, for centuries. I didn’t see this, though. I was a teenager, and my grandmother had just died, and what I saw was her house snipped out of context, her past closed off to me and bulldozed over.

The last thing my grandmother had told me before she died, struggling to speak through her Parkinson’s tremors, was about a storm that had moved across the parish when she was a child: how the wind howled, the walls of Rienzi shook. She told me—urgently—that she’d left a clothesbrush on a table outside. The wind had picked it up, she said, and then laid it right back down.

On the afternoon of November 23, 1887, the bodies of three black men were found in a thicket at Rienzi. By all indications, they had sought refuge there, shot and bleeding, during the massacre that morning that had claimed at least fifty-one black lives. Afraid, cold, and alone, the men had huddled together in the shelter of a bush and died.

By then a strike had been going on for nearly a month in Lafourche Parish, since the sugar planters had jointly refused to respond to workers’ demands. The workers, many of whom still lived in the slave cabins where they had been born, went on strike in the hopes of seeing an increased wage and the elimination of payment in scrip, which had kept them in conditions hardly distinguishable from those they’d experienced before emancipation. Aided by the state militia, the planters had charged all strikers remaining on the plantations with trespassing and forced them from their homes. Soon, evicted workers had filled every empty room in the city of Thibodaux and set up camp with their children and dogs along the roads leading into town, a recapitulation of the scene that had followed the enslaved workers’ liberation by Union soldiers just over two decades before.

Traveling into the city by train with the state militia, General William Pierce—who shot himself at his officers’ club a year after the massacre—described the sight of so many idle black people as if it were an emergency weather event: “I saw the fields in all directions full of cane, the mills idle, the stock and carts and wagons laid by and no work being done except on a few places, where planters had acceded to the demands of the strikers. . . . I was informed that had been the state of affairs for three or four days.”

Nearly two thousand strikers watched as the militia disembarked from the train. Horses, hitched to a Gatling gun, pulled it up the steps of the columned courthouse, and remained there in harness, ready to move in case of need. For almost three weeks, an uneasy peace prevailed in Thibodaux, and the militiamen grew antsy at their posts. Among the white inhabitants, rumors swirled that the strikers were planning to burn the town, and there were reports of nighttime shootings; two brothers went around firing into the sugar houses where work continued despite the strike leaders’ demands that all work cease.

Judge Taylor Beattie, a Republican and member of the Knights of the White Camelia (a more secretive version of the KKK), chaired a meeting at which it was resolved that the “state of disorder shall and must cease.” The assembled men made a pledge “to use every means in our power to bring the guilty parties . . . to a speedy detection and punishment.” A Peace and Order Committee formed—among them, Judge Beattie and my great-great-grandfather, Emile Morvant.

The town was cordoned as white “regulators” on horseback from Thibodaux and the surrounding parishes took to the streets. Mary Pugh, Beattie’s sister-in-law, wrote in a letter to her son that “everyone was on the watch least [sic] they would attempt some violence. White men were armed & guarded day & night.” When she found her son Peter molding bullets, he told her, simply, “We might need them.”

The shooting began in the cold predawn of November 23. Two sentries controlling the road leading to the back of town, where the black residents of Thibodaux lived, were warming themselves by a bonfire when shots were fired from out of a cornfield. One of the sentries fell into a ditch, wounded in the leg, and was escorted home. When his partner walked out to check on him, a bullet entered his left cheek and rolled out of his mouth. As Pugh wrote, “This opened the ball.”

White vigilantes on horseback poured through the back of town searching for the shooter, and soon gunshots accompanied the sound of hooves. Clarisse Conrad told of the shooting of all of the men in her family:

[My father] and my brother Grant and my Uncle Marcelin Welden and my mother and myself were all at home. The white men came to our house and they saw my mother in the back yard emptying a tub, and they told her if they had any men in the house to tell them to come out damned quick. Before mother could tell them to come out my father and brother and my uncle, being attracted by the noise, stepped out. . . . I heard my uncle tell them he wasn’t in it, and they said “get back you son-of-a-bitch” and shot him down and killed him. My brother was back of the house and got behind a barrel and the white men got behind the house and shot him dead. My father crawled under the house and they shot him under the house. He fell on his face when they shot him. After he fell on his face I heard them say “he is dead now” and “let us go.” My father was shot in both arms and was also shot in the breast. His collar bone was badly broken and some of the little bones came out. I know that my father was unarmed when the white men came and called him out.

Conrad’s father, who had not even been on strike, would later testify that he had been shot by his own employer, who feigned not to recognize him, and three other men.

I read an account of these events for the first time two years ago, when my father gave me a copy ofThe Thibodaux Massacre by John DeSantis. Since then, I have searched old newspapers—the Thibodaux Sentinel, the Iberville South, the Opelousas Courier, the Times-Democrat—for my great-great-grandfather’s name, to find out what specific role he’d had in the massacre that day. I found wedding announcements for his children and a story about a fourteen-year-old boy who, sleeping outside at one of Morvant’s plantations, had been awakened by the midnight whistle and fallen headfirst into a kettle of boiling sugar. I found the announcement of Emile’s and his business partner’s purchase of Rienzi nine years after the massacre, found a photograph of him standing beside a steam engine in the cane. Finally, there’s a notice of his partner’s purchase of the Morvant shares. In articles relating to the massacre, his name is listed only once, as a member of the Peace and Order Committee. But that’s no surprise; no other white men, with the exception of the two sentries, are mentioned anywhere else either. A statement made by Judge Beattie, the sheriff, the lieutenant governor, and the mayor controlled many of the reports. According to their account, after “two of the most respectable and esteemed young men of our town” were wounded, other sentries rushed to them and were shot in turn. When “armed guards of the town rushed to the scene of action, they were again fired upon from ambush, and then returned the fire by a general fusillade, which was kept up until the rioters were dispersed.”

According to statements by the victims, however, shooting continued for six hours, during which time many of the striking workers who had filled Thibodaux fled into the woods and cane thickets that surrounded the town. At least fifty-one black men, women, and children were killed, though other estimates range as high as three hundred. An inquest on the day of the massacre only investigated the deaths of eight people who lived in Thibodaux and whose deaths could not, therefore, be ignored. Adjudged by men from the Peace and Order Committee, it was determined that the dead were killed by “persons unknown.”

“We’ll bet five cents that our people never before saw so large a black-burying,” reported the Lafourche Star, but where that burial took place is lost to history. DeSantis suspects that there is a mass grave beneath what is now an American Legion Hall in Lafourche Parish. This parcel of land, known as the “graveyard” to locals, is likely where the murdered strikers who’d sought refuge in town after having been evicted from nearby plantations were buried.

I have seen, however, the grave of Mary Pugh. She was buried behind Madewood plantation during a period of vacancy. Arriving there, her son Allen wrote in a letter, “It seemed for a moment as if the house, so deserted looking with its huge Corinthian columns, were some mausoleum, and that we should lift her up tenderly, carry her inside and leave her within its protecting walls.” The graveyard is small, only half-filled with people who’d meant to rule there longer. Nevertheless, Katherine Beattie, the daughter of Fannie Pugh Beattie and Taylor Beattie, is also there, her headstone marked with a long span, 1872–1968, and the epitaph: INVICTUS.

From a distance, the National Memorial for Peace and Justice in Montgomery, Alabama, looks like a vast colonnade. A thin roof is supported by an uncountable number of abstract caryatids—corten steel columns, the color of dark skin, the color of dried blood. As my family enters, the columns, each the height of a grown man, confront us bodily—rusted ghosts—but as we walk among them, they become, for a moment, the grave markers that they are. As we circle an inner courtyard, the ground begins to fall away. Slowly, the columns rise. Soon, we are at eye level with their feet, and then they dangle high above us, heavy with the memory of the hanged.

As I look up at the columns, I feel in my neck the crane of the white women who watched, holding on to the shoulders of their children, as their neighbors lynched their neighbors—hanged them, burned them, stoned them, drove corkscrews into their flesh—for offenses against the racial power structure:

Warren Powell, 14, was lynched in East Point, Georgia, in 1889 for “frightening” a white girl.

David Hunter was lynched in Laurens County, South Carolina, in 1898 for leaving the farm where he worked without permission.

Anthony Crawford was lynched in Abbeville, South Carolina, in 1916 for rejecting a white merchant’s bid for cottonseed.

Grant Cole was lynched in Montgomery, Alabama, in 1925, after he refused to run an errand for a white woman.

Elbert Williams was lynched in Brownsville, Tennessee, in 1940 for working to register black voters as part of the local NAACP.

The names of these men, women, and children are engraved on the columns hanging above us. All around, visitors search for ancestors or for the names of neighbors, long unspoken. Each time my husband and I find a place we claim—Harris County, Jefferson County, Orleans Parish, Jefferson Parish, Lafourche—I read out the names of those whose deaths our ancestors had in some way caused, whose deaths we in some way benefitted from, names whose familiarity, in some cases, reflected other, older thefts of life, liberty, labor, body, justice, self.

The column holding the dead of Lafourche—massacred for refusing to bring in the cane—uses the smallest font, because it bears the longest list of names:

03.06.1877

WILLIAM WATSON

11.21.1887

ARCHIE JONES

11.23.1887

FELIX PIERRE

11.23.1887

FRANK PATTERSON

11.23.1887

GRANT CONRAD

11.23.1887

MAHALA WASHINGTON

11.23.1887

MARCELIN WELDEN

11.23.1887

RILEY ANDERSON

11.23.1887

WILLIS WILSON

11.23.1887

UNKNOWN

11.23.1887

UNKNOWN

11.23.1887

UNKNOWN

11.23.1887

UNKNOWN

11.23.1887

UNKNOWN

11.23.1887

UNKNOWN

11.23.1887

UNKNOWN

11.23.1887

UNKNOWN

11.23.1887

UNKNOWN

11.23.1887

UNKNOWN

11.23.1887

UNKNOWN

11.23.1887

UNKNOWN

11.23.1887

UNKNOWN

11.23.1887

UNKNOWN

11.23.1887

UNKNOWN

11.23.1887

UNKNOWN

11.23.1887

11.23.1887

UNKNOWN

11.23.1887

UNKNOWN

11.23.1887

UNKNOWN

11.23.1887

UNKNOWN

11.23.1887

UNKNOWN

11.23.1887

UNKNOWN

11.23.1887

UNKNOWN

11.23.1887

UNKNOWN

11.23.1887

UNKNOWN

11.23.1887

UNKNOWN

11.23.1887

UNKNOWN

11.23.1887

UNKNOWN

11.23.1887

UNKNOWN

11.23.1887

UNKNOWN

11.23.1887

UNKNOWN

11.23.1887

UNKNOWN

11.23.1887

UNKNOWN

11.23.1887

UNKNOWN

11.23.1887

UNKNOWN

11.23.1887

UNKNOWN

11.23.1887

UNKNOWN

11.23.1887

UNKNOWN

11.23.1887

UNKNOWN

11.23.1887

UNKNOWN

11.23.1887

UNKNOWN

11.23.1887

I read it aloud to my daughter, those unknowns like a heartbeat. Tired and sweaty, she leans against my legs.

“Why did we have to go here?” she asks me as she slumps in my lap under the hanging columns.

“Because we have to understand the truth about our past and about America,” I say, “so we can tell people who still don’t know.”

A woman walking near us nods. It feels like a sign of peace.

“Truth telling,” writes Sherrilyn Ifill, is “a critical form of reparation.” In her book On the Courthouse Lawn: Confronting the Legacy of Lynching in the Twenty-first Century, she examines the silences that surround racial terrorism: the violently enforced silence of black communities and the self-acquitting mythologies of white ones. Because white supremacy is a story we tell—one that erases the stories of those it oppresses, one that relies on the silence of both its victims and its beneficiaries to be heard—retelling the story of America is essential in any movement toward justice. Such a retelling, however, requires from most white Americans that we learn to re-see and, in some cases, reconstruct our world.

“Architecture spatializes political, social, and historical relationships,” writes architect Mario Gooden. In his book Dark Space, he makes the argument for a new architecture that breaks down hegemonic structures by refusing the exclusionary symbolism of conventional Western architecture. Resistance in architecture requires making spaces that encourage action rather than stasis. Foucault wrote in an interview with anthropologist Paul Rabinow:

Men have dreamed of liberating machines. But there are no machines of freedom, by definition. . . . It can never be inherent in the structure of things to guarantee the exercise of freedom. . . . If one were to find a place, and perhaps there are some, where liberty is effectively exercised, one would find that this is not owing to the order of objects, but, once again, owing to the practice of liberty. . . . [Architecture] can and does produce positive effects when the liberating intentions of the architect coincide with the real practice of people in the exercise of their freedom.

In order to create landscape that encourages liberation, we need to understand, as Foucault did, that space itself cannot free us—it is only our action in space that can bring us closer to justice. As America’s racial hierarchy was not, of course, simply upheld by architectural symbolism but enforced by centuries of constant violence, any renewed landscape must encourage an opposite action toward peace. The Memorial for Peace and Justice, designed by a multiracial team at MASS Design Group, does this better than any other space I have yet encountered.

While columned plantation houses, like Renaissance cathedrals, used symbolism to create stasis, the Memorial for Peace and Justice demands movement. The pillars shift in meaning from columns to spirits to grave markers to men, challenging us not to accept our first way of seeing but to allow our perception to change as we move through space. The names of the murdered men, women, and children are high and difficult to see: we squint. We seek out the names of our home counties and parishes, also the homes of the people who murdered them.

The memorial’s sister museum by the river—a former warehouse where enslaved people were kept before their sale—explains that white supremacy did not end with slavery but persists, flowing, through Reconstruction, Redemption, Jim Crow, and Mass Incarceration, in one unbroken line. The place is dense with stories, the exhibits ordered but nonlinear, so that visitors must choose where to listen, what to learn: whether to read flyers listing the names of children up for auction or to examine the earth collected from lynching sites, whether to uncover the image of a lynching or to sit in a visitation booth across from a man, jailed at thirteen, still serving life without parole.

Its primary subjects, however, are us, the visitors. The museum and memorial act as dredges to unearth the buried—the hushed histories, the lies and mythologies that we carry. As we move through the exhibits, docents wait, receiving with preternatural calm our stupid questions:

“Excuse me? Excuse me, I’m confused. I saw some women’s names up there. But it was only men who were lynched, right?”

“Can you explain to me: What is redlining?”

“So, this is saying the War on Drugs was racially motivated, that Nixon did it on purpose? On purpose.”

“The idea is white people are supposed to take these plaques home, right. You want us to admit that this is true?”

This last question a white woman asks under a tent at the memorial as she presses a bottle of cold water to her face. The docent looks out over the grounds, where replicas of the memorial columns lie like coffins in the sun. The idea, he explains, is to bring them home—for visitors to arrange with their city governments or county seats to have the memorials placed in the town square, where most lynchings were committed in the light of day, by groups of men, in the midst of crowds. Through this action, the complicity of regular citizens in racial terror might be counteracted by acknowledgment, the first step toward reconciliation. Every time a county claims its monument, the docent told me, the memorial will replace it with a bed of flowers.

“You see, it looks like a graveyard now, doesn’t it?” he says. “Soon it’s going to be a garden.”

“A Distant View” (2003) © Carrie Mae Weems. Courtesy of the artist and Jack Shainman Gallery, New York

“A Distant View” (2003) © Carrie Mae Weems. Courtesy of the artist and Jack Shainman Gallery, New York

The Southern landscape is not fixed, some archeological site full of ghostly buildings locked in time. In fact, white supremacy is enforced by this idea of stasis—by the assumption that the places where we live are neutral and natural rather than constructed by human actions. No, the way we act in space creates its meaning; by bulldozing slaves’ quarters or carrying bloodied earth, we change the geography of where we live.

In a vitrine filled with earth collected from the sites where people were murdered, one small green shoot sprouts. My husband lifts my daughter onto his shoulders, and we carry her back across Montgomery. The sun is high and hot as we walk down the empty Sunday sidewalks, reading signs: past the church where Dr. King was pastor, past the demolished department store that fired Rosa Parks. This city remembers itself, its crimes and its triumphs, better than most, and yet, on this day, it seems hardly to be there—half its people flown to the suburbs, the other half sitting inside in air-conditioned cool. As we watch a group of people unloading produce from the trunk of a Cadillac Seville, an antique bus rumbles past. Empty, it rattles over the intersection, carrying the battered ghosts of the Freedom Riders.

I think, as we walk past all of these relics of protest, about the march I’d joined a few months before, organized by Take ’Em Down NOLA, the citizens’ group behind the movement to remove Confederate monuments and other symbols of white supremacy from New Orleans. That Saturday, we walked from Congo Square—a site where enslaved Africans gathered to sing, dance, and sell goods often in the hopes of earning enough to buy their freedom—to the statue of Andrew Jackson in the heart of the French Quarter. A band led us, brass and drums, and as we shuffled and danced along the route, some of us holding drinks, men and women in kitchen whites came out of the service entrances of the restaurants where they worked. Wrapping her hands around the bars of an alley’s gate, an older black woman yelled out to ask what we were up to. When someone told her, she nodded her head and smiled, and then went back in to her work.

I wondered that day, and wonder again now, walking through Montgomery, what this nation will look like if one day its black and white citizens acknowledge the same past, share the same geography. What would it be like, to live in a nation built on truth? In the last weeks, we’ve learned of the actions of ICE officers at our border, heard of babies ripped from mothers’ breasts, children taken from their fathers’ arms. My daughter is shocked. We are all shocked. It feels new, though it is not. At a fountain in the center of town that drenches the spot where men sold men and women and children away from their families, a small group is gathered in the shade of the trees to protest. We join them for a while, with a sign made in the hotel the night before. No one walks past, but we keep yelling.

Enjoy this story? Subscribe to the Oxford American.