Photos by Brian Chilson | Collage illustration by Carter/Reddy

A Hometown Kind of Thing

By Oxford American

Creating the No Tears Suite

I

n September 2017, the Oxford American premiered the No Tears Suite, a large-ensemble jazz composition in honor of the sixtieth anniversary of the Little Rock Central High School desegregation crisis. Written by Little Rock jazz pianist Chris Parker and vocalist Kelley Hurt, the piece was inspired by Melba Pattillo Beals’s memoir Warriors Don’t Cry, and the performance took place at the historic Magnolia Mobil service station, on the campus of Little Rock Central High School National Historic Site. Musicians included Grammy-winning drummer Brian Blade, bassist Bill Huntington, and several woodwind and brass players from the region.

Moved by the suite’s first iteration and eager to share it on a larger stage, the OA presented a reprise of the original performance in March 2019, this time incorporating fifteen musicians from the Arkansas Symphony Orchestra, conducted by Geoffrey Robson. Arranger/composer/bassist Rufus Reid was commissioned to write the new symphonic arrangements, and the seven-piece jazz ensemble included Parker (piano), Hurt (vocals), Blade (drums), Reid (bass), Bobby LaVell (tenor saxophone), Marc Franklin (trumpet), and Chad Fowler (alto and baritone saxophone). The new composition premiered at the Mosaic Templars Cultural Center, with a second, free-of-charge performance in the auditorium of Central High School.

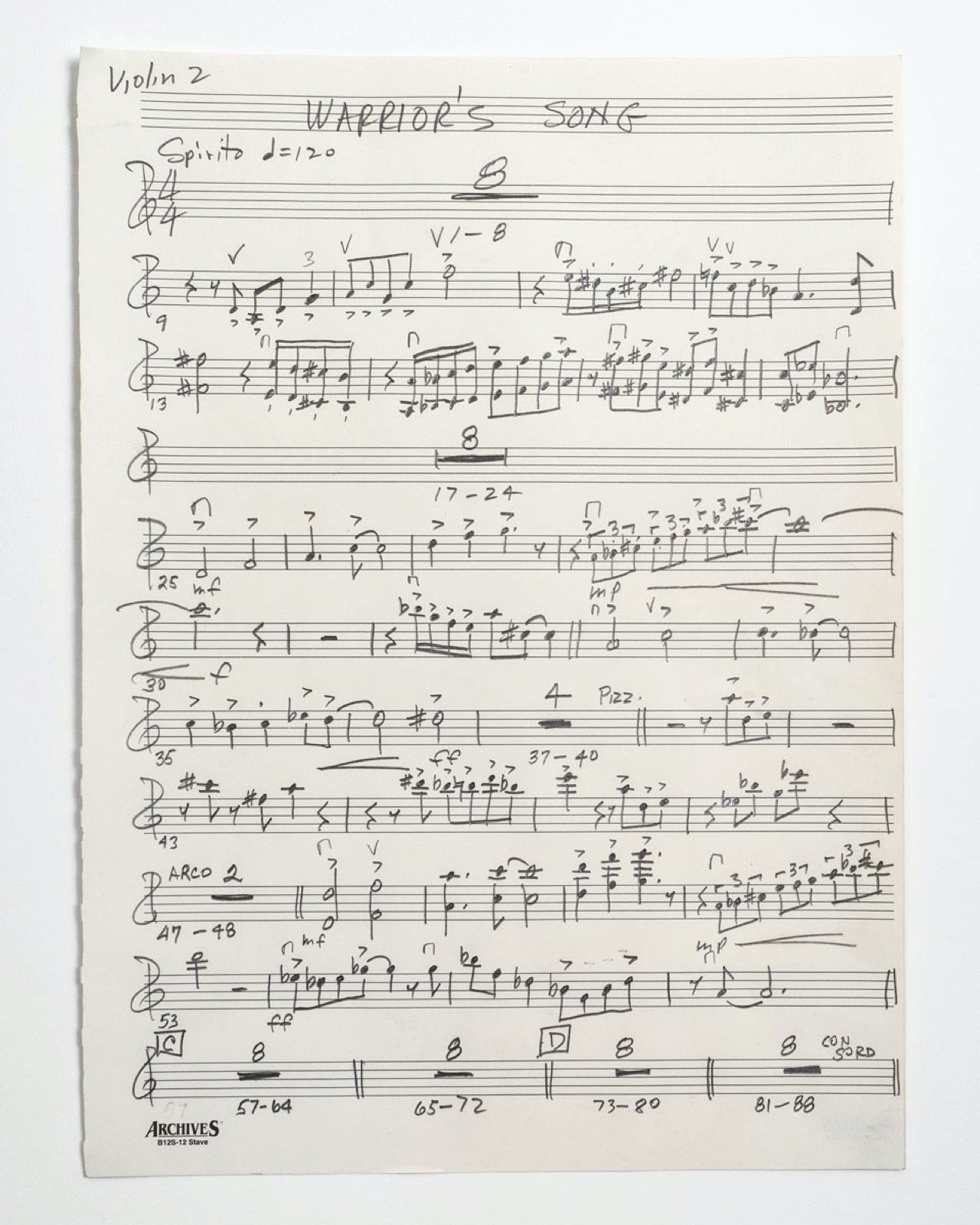

This iteration was not without complication. During their dress rehearsal, the musicians made a troubling discovery. Due to a technical error, Katherine Williamson—sitting principal second violin for the suite—had received sheet music containing many incorrect notes. No accessible digital files of the music existed, and Reid was left with no option but to rewrite the notes in their entirety by hand. With less than three hours until the suite’s world premiere, he returned to his hotel room and transcribed the correct music just in time for the show. The first sheet of that movement, titled “Warrior’s Song,” is pictured below, on loan from Williamson, written in Reid’s own precise and elegant style.

A month after the event, we sat down with Reid, Parker, and Hurt, and they reflected on the experience of performing the No Tears Suite. They spoke about the process of creative collaboration, Arkansas’s lasting legacy of the Little Rock Nine, and the unique pressures and inspirations of art-making in the South.

—The Editors

Rufus Reid: When Chris asked me to collaborate, I really didn’t know what exactly he wanted me to do. I’m not sure he knew exactly what he wanted me to do, but he had faith in me to augment what he had written . . . to enhance it in some way. It took me a little longer to just ponder and think about that. After a while, though, the melodies that Chris made became quite infectious. You wake up and you start singing some of those songs, and that means they’re really starting to get under your skin. That’s when I began to hear other things on top of that.

Chris Parker: One day in December, before the performance, I called Rufus and he said, “Man, I’m just sittin’ up here listening to your tunes,” and I’m goin’, What? I looked at Kelley and said, “Rufus Reid is humming my music.” That messed me up! He was immersing himself to the point that he became so familiar with the music that he could add his own thing. So some of the stuff you hear in there is my music, some of it was stuff he created, and no one will ever know but us. To me, that’s a hell of a compliment, to have someone like Rufus Reid say, “I’m gonna take you seriously enough to actually listen to something of yours and put my stamp on it.”

RR: The most difficult moment for me was when I encountered Kelley’s vocals, in the “Roll Call” movement, where she recites the names and backgrounds of each member of the Little Rock Nine. I thought, What am I going to do here? The harmony was pretty static, spoken-word. I started to improvise. I said, “Well, we’ve got these nine names; maybe we can give them each a different sound. Nine different instruments to portray each one.”

Kelley Hurt: I edit and take things out, put stuff in and remove it. We altered things up until the very moment that we played. In that way, the performance is fluid, evolving as we learn more. It’s a living art piece.

RR: I hadn’t been to Little Rock until the performance, and to be able to go to the museum across the street, to be reminded with videos how horrific that moment was, to actually play in that school, that was deep. To know that this is something that’s so heavy, something we’re still going through, even. To be there in the same town, on the same block, in the exact same building and onstage, in that beautiful auditorium. It was an emotional time.

CP: It was a hometown kind of thing. I grew up here, and all my life, whenever you bring up Central High and 1957, either the conversation is going to be negative or people don’t want to have that conversation. And yet we were one of the first states to force integration. Many other states dragged their feet much worse than us. We should be celebrating what happened then, but that also means you have to acknowledge that huge parts of our community were racists who wanted to tear nine kids limb from limb. They were prepared to do it. A lot of white people have a lot of guilt and shame about that, and a lot of black people are quite pissed off about that. But if you look at the fact that we’re the community that produced these people—the ones that finally said we’re gonna do it, we’re gonna put this on the calendar—then we actually have something to celebrate. That flipped the narrative for me. Even my father will say, “Man, that was just all so ugly,” and yes, in truth, it was ugly. But we came out of that year with nine heroes.

KH: We treat it more as a celebration than as something terrible that happened. It’s a celebration of those young people that had the courage to bring attention to themselves. That’s a hard decision to make when you’re a kid. It affects your parents, your family, your friends, your neighbors, people you interact with every day.

I grew up in Memphis, and that city holds a lot of weight. The assassination of Dr. King is something that changed the city forever, the way people interacted with each other, and especially the music. Coming from there to Little Rock, you start to wonder, Do all cities have this kind of weight? When I first moved here with Chris, we met historians that talked about the Little Rock Nine, and after living here for a while, I saw the statues on the north side of the Capitol and was like, “Who is that?” Chris said, “That’s them.” I couldn’t believe I’d been here all this time and never noticed it.

CP: In a way, we’ve disconnected ourselves from this event because there’s so much shame around it, but there was some kind of silver lining. They brought an issue to a head. It was the [Daisy and L. C.] Bates family that did that. They said, “You know what, we’re gonna do this. We’re gonna recruit and train these kids.”

Courtesy of Katherine Williamson

Courtesy of Katherine Williamson

Enjoy this story? Subscribe to the Oxford American.