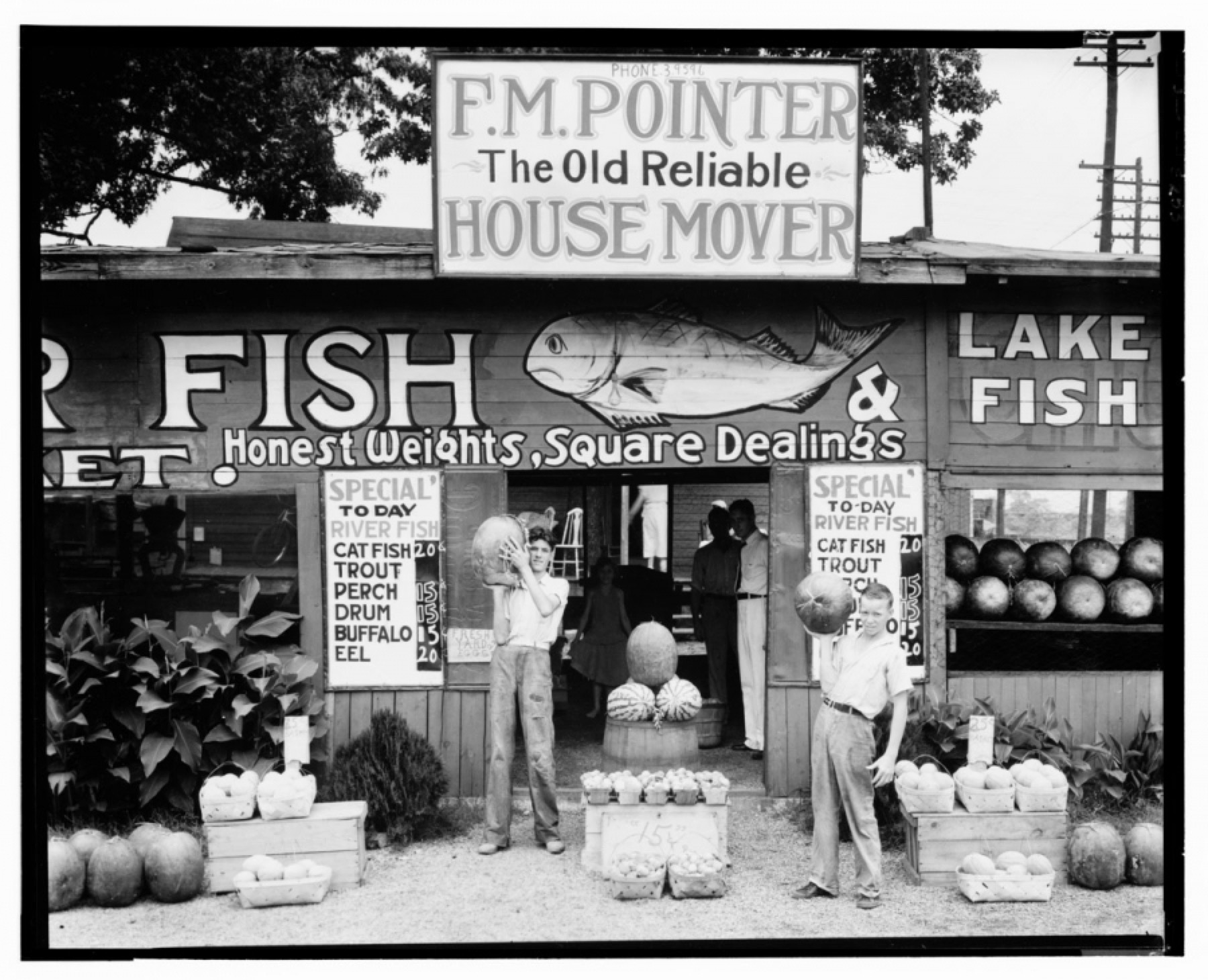

“Fish Market Near Birmingham, Alabama” (1936), by Walker Evans. Courtesy Library of Congress Prints and Photographs Division Washington, D.C. [LC-DIG-fsa-8c52874]

Getting the Look

By John T. Edge

L

ate this past summer, my friend Wright Thompson texted me a picture of a Birmingham fish market. On the way back to Oxford, Mississippi, where we both live, Wright had somehow ended up on Vanderbilt Road, west of a massive railroad switchyard in Collegeville. Interstate construction had recently changed how cars move through the city, forcing traffic onto a post-industrial streetscape of abandoned gas stations and empty parking lots. Once dominated by coke furnaces, steel mills, and chemical plants, the area is now thick with scrap dealers and junkyards.

Just short of the tracks, he had snapped a cell phone picture of a concrete block building, painted teal and white. Wright thought I might find a story there. A quick web search confirmed his good instincts. River Fish Market, the name by which it operates today, is probably the business that Walker Evans shot in 1936 while working for the Farm Security Administration to document American life during the Great Depression.

Captured head-on in the style of the penny postcards that Evans admired and collected, that market photo might be the most beloved of his images. John T. Hill, his friend and frequent collaborator, recently told me that Evans’s various obsessions are all there in one black-and-white frame: an appreciation for vernacular architecture and media, a want to render three-dimensional subjects as one-dimensional, a preference for making images without artifice.

Smart people read that photo in different ways. Some see a sentimental take on a changing America. Others read it as naive capitalism, documented in a moment when folk culture gave way to mass culture. Hill connects Evans to Giotto, the Italian painter who manipulated perspective to flatten depth of field and create abstractions. What I see at first is a simple document of a simpler past. Months passed before I began to recognize what Hill’s observations implied or what Roland Barthes meant when he wrote that cameras could be “clocks for seeing.”

Two Christmases ago, my wife, Blair, gave me a couple of prints by Jerry Siegel, a photographer with deep roots in Alabama, where she grew up. One shows a statue of Venus, mounted between two pumps at a Black Belt filling station. The second portrays a young black girl at a county fair in Selma, aiming a toy rifle at a stack of red, blue, yellow, and white cans. Think like a photographer and you see the shapes that may have caught Siegel’s eye. Stacked together, viewed down the barrel of the girl’s gun, those cans recall a color-field painting.

I had fallen in love with the photograph a year before that, when I met Siegel after he gave a lecture in Oxford. At first, he hadn’t seen the image that looms in front of the girl and behind those cans, Siegel had told me. Only when he developed the print did Siegel notice the Confederate battle flag in the background. Only with distance from the moment did he see the moment. As he talked, I learned to think about his photograph in a new way.

Now when I look, I see more than a black girl with a gun who has trained her sight on a prize. I see a metaphor for Confederate retentions. Whenever we regard the South, Siegel’s photo suggested, those symbols remain forever in the frame. Even the keenest eyes sometimes miss them. But they’re always there. In the year since Blair gave me that photograph and we hung it on our living room wall, I have looked more closely at many different photographs that offer many different ways to see the South, often wondering what they have to tell me that I can’t quite see.

Walker Evans began traveling for the FSA in the summer of 1935. Until he took a leave of absence in 1936 to live in Hale County and work on the project that would become the book Let Us Now Praise Famous Men, he shot seashell-spackled tabby houses in coastal Georgia; a wood-framed storefront barbershop in Vicksburg, Mississippi; and martin houses made of hollowed gourds in the Alabama Black Belt. The last one of those would appear in the front of the book. The other two, along with his photograph of the fish market and a few hundred others, would become a memory bank for the nation, tapped by generations to come.

Often working a tripod-mounted 8x10 camera, which he focused beneath a drape, Evans catalogued the America of his era and shaped the identity that Americans would carry forward. Time passed through his camera, pausing long enough for Evans to frame moments that changed our collective mind about what images should be captured and what narratives should be preserved. To paraphrase his FSA peer Dorothea Lange, Evans taught America how to see once we put down our cameras.

Much of Evans’s photography is now in the public domain. That means bad prints of his sharp and insightful work are everywhere. In bad prints, like the one used on the cover of a travel journal I once carried on a bike ride through France, these figures are spectral. Or they are lost to the shadows, like the ideas that animate Evans’s work and the lessons that his documentary-style photographs yield.

But stare at a really good print of an Evans picture, like the archival pigment prints Hill produced a few years back, and there is much to learn. Turns out, the fish and produce market Evans shot was a façade of plank boards and chicken wire, built directly in front of what appears to be a home. Look close: In addition to the two boys who stand before the market, hefting black-green watermelons that trail vines, one dog, three men, one woman, and one girl come into focus.

If you gain access to the three alternate negatives that Evans exposed that day, more details emerge. Chairs, stacked on the porch of the house behind the market, make clear that a moving company, advertised on the sign above the door, did business in the same space. A bicycle, propped on a kickstand, visible beneath the T in the word MARKET, suggests that the Frank M. Pointer family, owners of the moving company and the market, may have also lived here.

Questions arise, too. Is one of the figures at the center of the porch repairing a chair? Down on the end of the porch, what is that angular, akimbo shape? A sausage grinder? A pea sheller? When you see these images clearly and account for historical context, you want to know what truths a façade like this can hide or present.

For the past year I’ve been trying to figure out how to write a book about why I became unsettled in my boyhood home, how I searched for other homes while in my twenties and thirties, how I found ways to belong in bars and restaurants in my forties, why I have now happily settled in Oxford in my fifties, and what those observations have to do with one another. It will not surprise you to learn that I spend much of my time in a fitful search for unifying metaphors.

Late in October, Wright and I saw Aaron Sorkin’s retelling of To Kill a Mockingbird in a packed New York City theater. Designer Miriam Buether, it seems, marked transitions with the rise and fall of what looked like a red brick wall. As soon as we settled into our seats, I thought of William Christenberry, who had taken inspiration from Evans and who had retraced Evans’s travels in the Black Belt of Alabama, documenting the corrosions and embellishments of time, famously returning each year to a minor building in the woods, wrapped in tarpaper made to look like red brick.

Buether’s set does comparable work to the photographs of Evans and Christenberry, I reckoned, walking out of the Shubert. All allow us to inhabit spaces we don’t know. Drawing on these images, we project ourselves into ready-made scenes. And we imagine alternate pasts and futures. Like a good bar or a good restaurant, that play and those photographs enable us to be someone else for a moment or a night, to step through a façade and walk around in someone else’s shoes, as Atticus Finch put it in the book Sorkin adapted.

Four months after Wright texted me that image, I planned an Atlanta trip that allowed Birmingham stops both going and coming. On the first cold day in December, I drove through Collegeville and the knot of communities known collectively as North Birmingham. If the place now known as the River Fish Market had survived since 1936, I wondered, what else from that era would I see if I moved slowly and looked closely?

Early that morning I pulled to a curb on 29th Street, a mile and a half southwest of the market, and got out of the car with my camera. A block of seemingly deserted businesses stretched before me. I shot a garage, painted a dull green and framed by the white, stencil-painted legends TRUST, IN GOD, and FAITH. I captured a brick building, once white, fronted by rusted metal doors and flanked by pairs of rusted metal shutters. I photographed a mustard yellow building, tattooed maroon by a cascade of runoff. I saw the empty street through Evans’s eyes, looking for shapes and patterns and symmetry, thinking about that New York City stage, imagining the characters that might animate this place.

As I drove closer to the market, people came into view. At the scrapyard across the street, men in yellow slickers sorted junked metal, unloading pickups stacked with busted hot water heaters, twisted bed frames, and rusted scaffolding. I swerved to avoid two men in orange vests, pushing shopping carts loaded with aluminum cans down the center of the street. After a crossing signal clanged, just before a train double-stacked with orange shipping containers swooshed by, I watched one man in a sideswiped Datsun gun it to beat the train while another waited patiently at the tracks, straddling a ten-speed bike with a two-bowl cast iron sink strapped to the rear. The stage was set, the play was in motion.

The next day, on the way back through town, I met Wilson John Crasta, who had recently bought the River Fish Market from a guy whose Arabic name translates as Promise, who bought it from someone whose name I never learned, who likely bought it from Kent Scott, whose father probably bought it from Pointer, the man who made a market in watermelons, fish, and moving services.

Crasta wasn’t there when I arrived. Arthur Moore, who serves as a sort of informal security guard, put away his breakfast of corn puff cereal and let me in. Since he began having seizures in 2006, Moore told me, he has hung out here while his wife works. Those seizures, he said, rubbing the back of his head, “That’s not something to want.” As we talked, he looked over my shoulder, tracking developments in a Lifetime movie. “Somebody killed his father-in-law,” he said.

I had arrived with expectations. When I was a boy, my father and I shopped at a fish market somewhat like this one, where the owner displayed whole fish on a bed of crushed ice in a tin trough. Most Fridays we returned home with catfish steaks, wrapped in sodden newspaper. Blair plays similar childhood memories in her head, of a market in Opelika, set alongside a welding shop, where she and her mother skirted a shower of sparks to buy Gulf shrimp on Friday afternoons. I came looking for some version of those places, overlaid with the image Evans captured.

Much has changed here since Evans shot his famous photograph, I learned from Crasta, a native of Mumbai, India, who moved here in 1998, and who, back home, ate mackerel and pomfret and a boney fish he called korly. Now, none of the fish he sells come from local waters, he told me, saying Alabama laws make it tough for him to sell river fish. A small man with eager eyes who makes his real money buying and selling used cars at auction, Crasta no longer sells eel like Pointer did. But he still stocks buffalo fish, which he buys from a Korean market in Atlanta. And he still fries bream hard to order.

Eating fried snapper filets and white bread, arrayed with stylish precision on tissue paper–lined red cafeteria trays, I watched Crasta reduce two fried bream to four glistening bones in less than ten minutes. And I learned that he plans to remodel the market, using the Evans photograph as a prompt. “Do you think it was like this?” he asked, holding out his cell phone to display a picture of a craftsman house, painted a color on the blue side of teal. “I want to get the look right.”

Like many who stand before an Evans photograph, I had come looking for a past to inhabit, a cast of characters to join. And so, in a way, had Crasta, who knows some of the history of the building and the photograph, and who told me that he plans to leverage interest like mine to build his market business. When I asked him to show me where he believed the precise building Evans photographed had once stood, Crasta showed me outside the door, along the side of the building, to the rear of the market, where what looked like a wooden lean-to was in shambles.

This current version of the market, he believes, was built in front of the ruins of the old. “It’s still here,” Crasta said, speaking of the façade that Evans captured eighty-plus years before, and of civilizations more generally. “It’s all here—you just have to look.”

Enjoy this story? Subscribe to the Oxford American.