Da Art of Storytellin' (A Prequel)

By Kiese Laymon

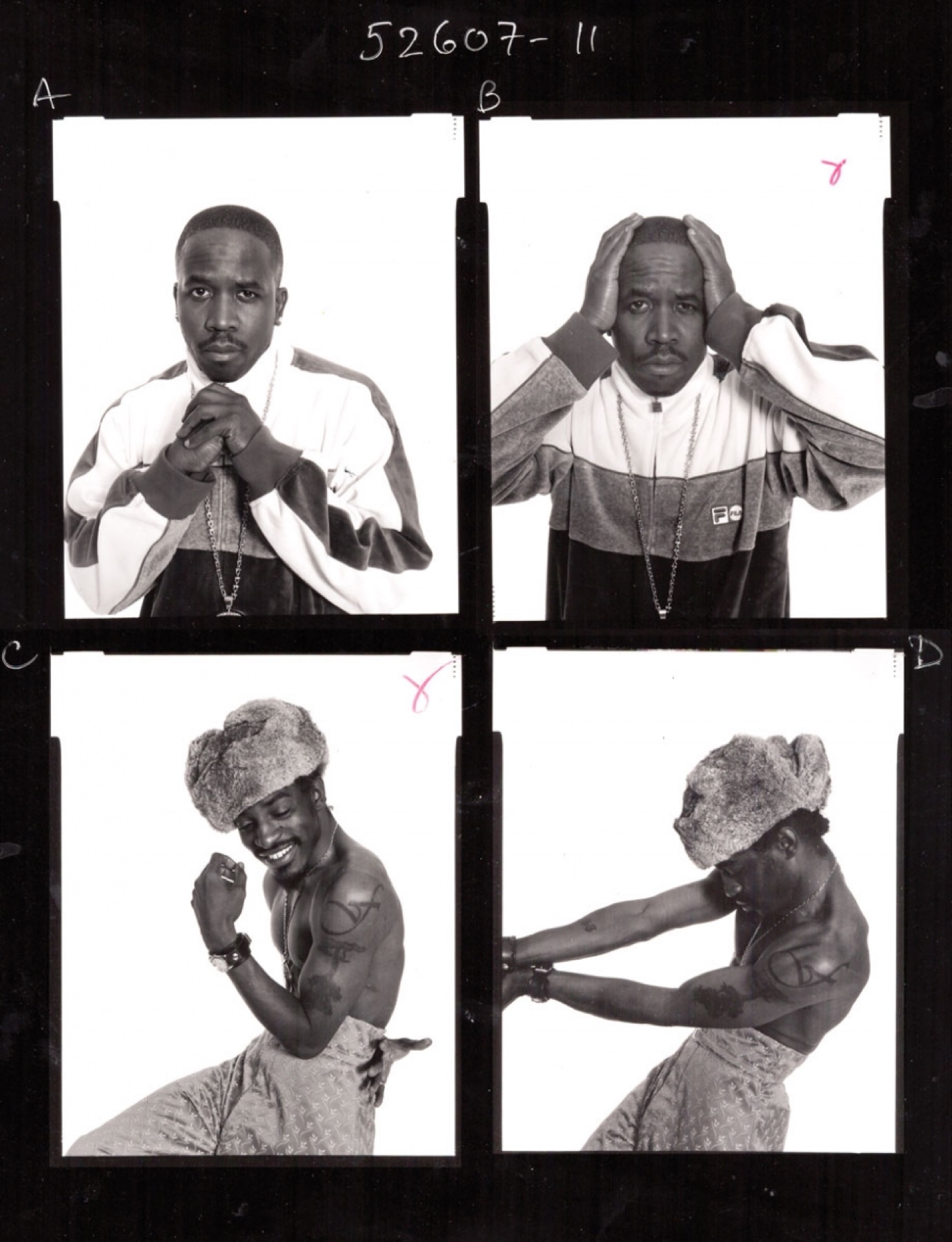

Photos of André 3000 and Big Boi by Janette Beckman

From six in the morning until five in the afternoon, five days a week, for thirty years, my Grandmama Catherine’s fingers, palms, and wrists wandered deep in the bellies of dead chickens. Grandmama was a buttonhole slicer at a chicken plant in central Mississippi—her job was to slice the belly and pull out the guts of thousands of chickens a day. Grandmama got up every morning around 4:30 A.M. She took her bath, then prepared grits, smoked sausage, and pear preserves for us. After breakfast, Grandmama made me take a teaspoon of cod liver oil “for my vitamins,” then she coated the area between her breasts in powder before putting on the clothes she had ironed the night before. I was ten, staying with Grandmama for the summer, and I remember marveling at her preparations and wondering why she got so fresh, so clean, just to leave the house and get dirty.

“There’s layers to this,” Grandmama often said, when describing her job to folks. She went into that plant every day, knowing it was a laboratory for racial and gendered terror. Still, she wanted to be the best at what she did—and not just the best buttonhole slicer in the plant, but the best, most stylized, most efficient worker in Mississippi. She understood that the audience for her work was not just her coworkers or her white male shift managers, but all the Southern black women workers who preceded her and, most importantly, all the Southern black women workers coming next.

By the end of the day, when the two-tone blue Impala crept back into the driveway on the side of our shotgun house, I’d run out to welcome Grandmama home. “Hey baby,” she’d say. “Let me wash this stank off my hands before I hug your neck.”

This stank wasn’t that stink. This stank was root and residue of black Southern poverty, and devalued black Southern labor, black Southern excellence, black Southern imagination, and black Southern woman magic. This was the stank from whence black Southern life, love, and labor came.

Even at ten years old, I understood that the presence and necessity of this stank dictated how Grandmama moved on Sundays. As the head of the usher board at Concord Baptist, she sometimes wore the all-white polyester uniform that all the other church ushers wore. On those Sundays, Grandmama was committed to out-freshing the other ushers by draping colorful pearls and fake gold around her neck, or stunting with some shiny shoes she’d gotten from my Aunt Linda in Vegas. And Grandmama’s outfits, when she wasn’t wearing the stale usher board uniform, always had to be fresher this week than the week before.

She was committed to out-freshing herself, which meant that she was up late on Saturday nights, working like a wizard, taking pieces of this blouse from 1984 and sewing them into these dresses from 1969. Grandmama’s primary audience on Sundays, her church sisters, looked with awe and envy at her outfits, inferring she had a fashion industry hook-up from Atlanta, or a few secret revenue streams. Not so. This was just how Grandmama brought the stank of her work life into her spiritual communal life, in a way that I loved and laughed at as a kid.

I didn’t fully understand or feel inspired by Grandmama’s stank or freshness until years later, when I heard the albums ATLiens and Aquemini from those Georgia-based artists called OutKast.

One day near the beginning of my junior year in college, 1996, I walked out of my dorm room in Oberlin, Ohio, heading to the gym, when I heard a new sound and a familiar voice blasting from the room of my friend John Norris, a Southern black boy from Clarksville, Tennessee.

We don’t contribute to your clandestine activity.I went into John’s room, wondering who was rapping about cod liver oil over reverbed bass, and asked him, “What the fuck is that?” It was “Wheelz of Steel,” from ATLiens. Norris handed me the CD. The illustrated cover looked like a comic book, its heroes standing back-to-back in front of a mysterious four-armed force: Big Boi in a letterman’s jacket with a Braves hat cocked to the right, and André in a green turban like something I’d only seen my Grandmama and Mama Lara rock. Big Boi’s fingers were clenched, ready to fight. André’s were spread, ready to conjure.

My soliloquy may be hard for some to swallow

But so is cod liver oil.

You went behind my back like Bluto when he cut up Olive Oyl.

Two things I hate: liars and thieves, they make my blood boil.

Boa constricted, on my soul that they coil.

John and I listened to the record twice before I borrowed my friend’s green Geo, drove to Elyria, and bought ATLiens for myself. Like Soul Food by Atlanta’s Goodie Mob, another album I was wearing out at the time—their song “Thought Process,” which featured André, had nudged me through the sadness of missing Mississippi a year earlier—ATLiens was unafraid of the revelatory dimensions of black Southern life. Like Soul Food, ATLiens explored the inevitability of death and the possibility of new life, new movement, and new mojo.

But something was different.

I already knew OutKast; I loved their first album, Southernplayalisticadillacmuzik, in part because of the clever way they interpolated funk and soul into rap. ATLiens, however, sounded unlike anything I’d ever heard or imagined. The vocal tones were familiar, but the rhyme patterns, the composition, the production were equal parts red clay, thick buttery grits, and Mars. Nothing sounded like ATLiens. The album instantly changed not just my expectations of music, but my expectations of myself as a young black Southern artist.

By then, I already knew I was going to be a writer. I had no idea if I would eat off of what I wrote, but I knew I had to write to be a decent human being. I used ink and the page to probe and to remember through essays and sometimes through satire. I was imitating, and maybe interrogating, but I’m not sure that I had any idea of how to use words to imagine and really innovate. All my English teachers talked about the importance of finding “your voice.” It always confused me because I knew we all had so many voices, so many audiences, and my teachers seemed only to really want the kind of voice that sat with its legs crossed, reading the New York Times. I didn’t have to work to find that cross-legged voice—it was the one education necessitated I lead with.

What my English teachers didn’t say was that literary voices aren’t discovered fully formed. They aren’t natural or organic. Literary voices are built and shaped—and not just by words, punctuation, and sentences, but by the author’s intended audience and a composition’s form. It was only after listening to ATLiens, discovering Toni Cade Bambara’s Southern Collective of African-American Writers, and reading the work of my Mama’s former student, the hip-hop journalist Charlie Braxton, that I realized in order to get where I needed to go as a human being and an artist, in order to release my own spacey stank blues, I had to write fiction. Toni Cade, Charlie, Dre, and Big showed me it was possible to create and hear imaginary worlds wholly fertilized with “maybe,” “if,” and “probably.”

I remember sitting in my dorm room under my huge Black Lightning poster, next to my tiny picture of Grandmama. I was supposed to be doing a paper on “The Cask of Amontillado,” but I was thinking about OutKast’s “Wailin’.” The song made me know that there was something to be gained, felt, and used in imitating sounds from whence we came, particularly in the minimal hook: the repeated moan of one about to wail. I’d heard that moan in the presence of older Southern black folk my entire life, but I’d never heard it connecting two rhymed verses. Art couldn’t get any fresher than that.

By the mid-nineties, hip-hop was an established art form, foregrounding a wide, historically neglected audience in completely new ways. Never had songs had so many words. Never had songs lacked melodies. Never had songs pushed against the notion of a hook repeated every forty-five seconds. Like a lot of Southern black boys, I loved New York hip-hop, although I didn’t feel loved or imagined by most of it.

When André said, “The South got something to say and that’s all I got to say,” at the Source Awards in 1995, I heard him saying that we were no longer going to artistically follow New York. Not because the artists of New York were wack, but because disregarding our particular stank in favor of a stink that didn’t love or respect us was like taking a broken elevator down into artistic and spiritual death.

With OutKast, Dre and Big each carved out their own individual space, and along with sonic contrast—Big lyrically fought and André lyrically conjured—they gave us philosophical contrast. When Dre raps, “No drugs or alcohol so I can get the signal clear as day,” I remember folks suggesting there was a smidgen of shade being thrown on Big Boi, who on the same album rhymed, “I got an ounce of dank and a couple of dranks, so let’s crank up this session.” If there was ever shade between them back then, I got the sense, they’d handle it like we Southern black boys did: they’d wrassle it out, talk more shit, hug, and come back ready to out-fresh each other, along with every artist who’d come before them in the making of lyrical art.

OutKast created a different kind of stank, too: an urban Southern stank so familiar with and indebted to the gospel, blues, jazz, rock, and funk born in the rural black South. And while they were lyrically competing against each other on track after track, together Big and Dre were united, railing and wailing against New York and standing up to a post–civil rights South chiding young Southern black boys to pull up our pants and fight white supremacy with swords of respectability and narrow conceptions of excellence. ATLiens made me love being black, Southern, celibate, sexy, awkward, free of drugs and alcohol, Grandmama’s grandbaby, and cooler than a polar bear’s toenails.

Right out of Oberlin, I earned a fellowship in the MFA program at Indiana University, to study fiction. For the first time in my life, I was thinking critically about narrative construction in everything from malt liquor commercials to the Bible. It was around that time that Lauryn Hill gave my generation an elixir to calm, compete with, and call out a culture insistent on coming up with new ways to devalue black women. In The Miseducation of Lauryn Hill, I saw myself as the intimate partner doing wrong by Lauryn, and she made me consider how for all the differences between André and Big Boi, they shared in the same kind of misogynoir on their first two albums. (Particularly on the song “Jazzy Belle”: “Even Bo knew, that you got poked / like acupuncture patients while our nation is a boat / Straight sinkin’, I hate thinkin’ that these the future mommas of our children.”) Miseducation had me expecting a lot more from my male heroes. A month later, OutKast dropped Aquemini.

Deep into the album, the song “West Savannah” ends with a skit. We hear a young black boy trying to impress his friend by calling a young black girl on the phone, three-way. When the girl answers, we hear a mama, an auntie, or a grandmama tell her to “get your ass in here.” The girl tells the boy she has to go—and then the boy tells her that his friend wants some sex. The girl emphatically lets the boy know there is no way she’s having sex with him, before hanging up in his face. This is where the next song, “Da Art of Storytellin’ (Pt. 1),” begins.

In the first verse, Big rhymes about a sexual experience with a girl named Suzy Screw, during which he exchanges a CD and a poster for oral sex. In the second, André raps about Suzy’s friend Sasha Thumper. As André’s verse proceeds, he and Sasha are lying on their backs “staring at stars above, talking about what we gone be when we grow up.” When Dre asks Sasha what she wants to be, Sasha Thumper responds, “Alive.” The song ends with the news that Sasha Thumper has overdosed after partnering with a man who treats her wrong. Here was “another black experience,” as Dre would say to end another verse on the album.

Hip-hop has always embraced metafiction. In the next track—“Da Art of Storytellin’ (Pt. 2)”—Big and Dre deliver a pair of verses about the last recording they’ll ever create due to an environmental apocalypse. We’ve long had emcees rhyming about the potency of their own rhymes. But I have never heard a song attribute the end of the world to a rhyme. In the middle of Dre’s verse, he nudges us to understand that there’s something more happening in this song: “Hope I’m not over your head but if so you will catch on later.”

Big Boi alludes to the Book of Revelation, mentions some ballers trying to unsuccessfully repent and make it to heaven, and then rhymes about getting his family and heading to the Dungeon, their basement studio in Atlanta—the listener can easily imagine it as a bunker—where he’ll record one last song. The world is ending. He grabs the mic: “I got in the booth to run the final portion / The beat was very dirty and the vocals had distor-tion!” Of course, this ending describes the very track we’re hearing, thus bringing the fictional apocalypse of the song into our real world.

I was reading Octavia Butler’s Kindred at the time Aquemini came out. Steeped in all that stank, I conceived of a book within a book within a book, written by a young Southern black girl whose parents disappear. “I’m a round runaway character,” was the first sentence my narrator wrote. I decided that she would be an emcee, but I didn’t know her name. I knew that she would tell the world that she was an ellipsis, a runaway ellipsis willing to do any and all things to stop her black Southern community from being written off the face of the earth. I scribbled these notes on the blank pages of Kindred while Aquemini kept playing in the background. By the time the song “Liberation” was done, Long Division, my first novel, was born.

I thought about interviewing André and Big Boi for this piece. I was going to get them to spend the night at this huge house I’m staying in this year as the Writer in Residence at the University of Mississippi. I planned on inviting Grandmama, too. Between the four of us, I thought we could get to the bottom of some necessary stank, and maybe play a game of “Who’s Fresher: Georgia vs. Mississippi.” But the interviews fell through, and Grandmama refused to come up to Oxford because I’m the only black person she knows here, and she tends to avoid places where she doesn’t know many black folks.

I kept imagining the meeting, though, and I thought a lot about what in the world I would say to Big Boi and André. As dope as they are, there’s nothing I want to ask them about their art. I experienced it, and I’m thankful they extended the traditions and frequencies from whence we came. Honestly, the only thing I’d want to ask them would be about their Grandmamas. I’d want to know if their Grandmamas thought they were beautiful. I’d want to know how their Grandmamas wanted to be loved. I’d want to know how good they were at loving their Grandmamas on days when the world wasn’t so kind.

The day that my Grandmama came home after work without the stank of chicken guts, powder, perfume, sweat, and Coke-Cola, I knew that her time at the plant was done. On that day—when her body wouldn’t let her work anymore—I knew I’d spend the rest of my life trying to honor her and make a way for her to be as fresh and remembered as she wants to be.

Due to diabetes, Grandmama moves mostly in a wheelchair these days, but she’s still the freshest person in my world. Visually, I’m not so fresh. I wear the same thing every day. But I am a Southern black worker, committed to building stank-ass art rooted in honesty, will, and imagination.

This weekend, I’m going to drive down to Grandmama’s house in central Mississippi. I’m going to bring my computer. I’m going to ask her to sit next to me while I finish this essay about her artistic rituals of labor vis-à-vis OutKast. I’m going to play ATLiens and Aquemini on her couch while finishing the piece, and think of every conceivable way to thank her for her stank, and for her freshness. I’m going to tell Grandmama that because of her, I know what it’s like to be loved responsibly. I’m going to tell her that her love helped me listen, remember, and imagine when I never wanted to listen, remember, or imagine again. I’m going to read the last paragraph of this piece to her, and when Grandmama hugs my neck, I’m going to tell her that when no one in the world believed I was a beautiful Southern black boy, she believed. I’m going to tell Grandmama that her belief is the only reason I’m still alive, that belief in black Southern love is why we work.

Enjoy this story? Subscribe to the Oxford American.