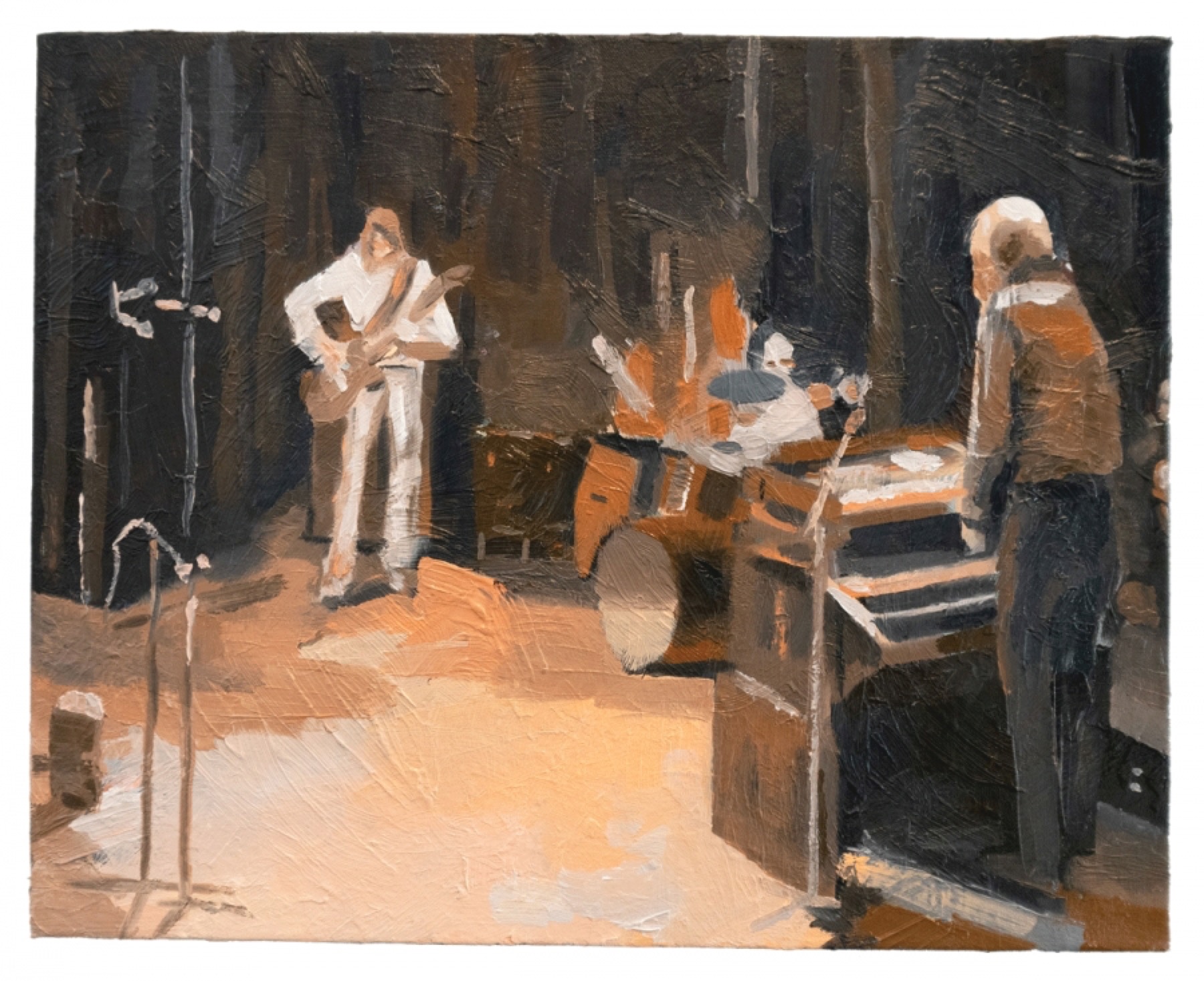

"On Ajoute Des Choses (no.8)" (2020), by Jason Jägel. Courtesy Gallery 16, San Francisco

I Know a Place

By Patterson Hood

Growing up Muscle Shoals

Iwas riding in the backseat of my godmother’s giant Oldsmobile Delta 88 with Sissy, my beloved maternal grandmother, at the wheel and my godmother, Ann Coldiron, in the passenger seat. The radio was on Q107, the 100,000 watt Top 40 station owned by Sam Phillips that blasted my hometown of Florence, Alabama, with all the hits during my childhood (it’s still there, blasting away). The song was “I’ll Take You There,” the No. 1 song in the nation at the time. The song is rightfully adored. Prince covered it many times during his performances. He was not alone. Rolling Stone magazine ranked the song at 281 in their list of the 500 Greatest Songs of all time. It was the nineteenth-biggest-selling song of 1972. That year, I was in second grade.

“I’ll Take You There” sings of a heavenly place where the troubles of its day are swept aside. It’s a simple song structurally. A vamp with the title repeated numerous times over an irresistible groove. A reggae-like bass line (influenced heavily from a song called “Liquidator” by the Harry J Allstars) and a very funky beat. The Staple Singers, a longtime family gospel group who had provided music for rallies and marches for Dr. Martin Luther King, were the vocalists. The song provided them with their first crossover secular No. 1 single. The backing group of musicians consisted of a bunch of Alabama white boys who called themselves the Muscle Shoals Sound Rhythm Section. They later came to be known as the Swampers.

I guess it was Sissy who told me that it was my dad playing bass on that song on the radio. In the car that day, I asked her to turn it up and she did. One minute, fourteen seconds into the song, lead singer Mavis Staples introduces the band during a musical breakdown. Barry Beckett plays a brief but enchanting piano solo as Mavis says, “Barry, Barry, Barry, play your piano now,” followed by a short and tasty guitar solo where she calls out her father, Pops Staples, on lead guitar, even though on that particular recording, the lead guitar was actually played by session guitarist Eddie Hinton (her father would be playing it when they performed live). Then the song seems to transform as the bass player goes up an octave and Mavis calls out, “David. Little David. Easy here, help me now. C’mon Little David. Alright.”

I was eight years old when I realized that Little David was my dad.

In the northwest corner of Alabama, there are four towns, three of which, Sheffield, Tuscumbia, and Muscle Shoals, sit nearly connected on the south side of the Tennessee River with only a sign to tell you when you have left one and entered the other. The fourth one, Florence, sits on the north side of the river. It is the biggest of the four towns, although the combined population of the entire metropolitan area is barely 200,000. That is probably close to twice what the population was back in the ’70s and ’80s when I was growing up there.

Locals can tell you in depth the differences between the four towns (and why they can never unify into one sizable population center that would carry far more political weight in state affairs). But to most outsiders, the entire region is better known as the Muscle Shoals area (or the Quad Cities).

Although it has come a long way, inching toward some sort of progress, the Shoals area that I grew up in consisted of two “dry” counties (Lauderdale and Colbert), meaning that to buy a beer you either went to a bootlegger or drove fifteen miles to the Tennessee state line, where you could find a few package stores and honky-tonks. To buy liquor you had to drive a good bit farther, an hour, to the closest towns that sold such things. Or, go to the bootlegger, of which there were many.

The Shoals area was as Bible Belt as it got, essentially controlled by one or two churches that worked hard to keep progressive ideas (on race, or gender, or sexuality), liquor, and any semblance of fun at bay. It was also the home of a musical miracle.

Between 1965 and 1982, hundreds of records were cut in Muscle Shoals at one or more of the several studios scattered around. Many of those records became hits, which led to an amazing array of major artists coming to my sleepy hometown to record at one of the humble little recording studios that had popped up there in the wake of a couple of regional soul hits that had come from FAME Studio. In 1966, Percy Sledge recorded “When a Man Loves a Woman” and sold millions of records. Shortly afterward, famed producer and Atlantic Records executive Jerry Wexler brought Wilson Pickett and then Aretha Franklin to town, where they recorded classic hits like “Mustang Sally” and “I Never Loved a Man (the Way I Love You).”

The Rolling Stones, Bob Dylan, Bobby Womack, Etta James, Paul Simon, Simon and Garfunkel, Rod Stewart, Willie Nelson, and Traffic all recorded hits there, as did a slew of soul acts and later country stars. In the late ’70s a sign went up declaring Muscle Shoals the HIT RECORDING CAPITAL OF THE WORLD, as more hits were cut there per capita than anywhere else. A record that probably still stands today.

The backing musicians on many of these hits were a bunch of country boys (mostly white) who had learned their instruments in one of the cover bands that played the SEC college circuit in the early ’60s. Over time the better players gravitated from frat parties to one of several groups of session players with names like the FAME Gang and the Muscle Shoals Sound Rhythm Section. My father was the bass player in the latter.

He began playing bass guitar professionally in 1966, just a couple of years after I was born. He wasn’t quite twenty-three when he played on Percy Sledge’s top-five hit “Warm and Tender Love.” Soon he was playing sessions, backing up the likes of Aretha Franklin, Wilson Pickett, Etta James, and Clarence Carter. If my dad’s career trajectory seemed unlikely, that paled in comparison to the odds of such a thing occurring at all in a small dry county in the Bible Belt. That so many of the most beloved soul hits of the civil rights era came from an integrated group of players just two hours north of Birmingham, where firehoses and police dogs were used against King’s marchers, is the kind of plot that’s too far-fetched for fiction and too unbelievable to be told without corresponding proof.

I guess I had been told from time to time that my dad was some kind of musician, but I’m sure that it had never quite registered until that fateful ride in the Oldsmobile, even though I had always loved music, especially the Beatles, whose song “She Loves You” was the No. 1 song the day I was born and whose breakup I heard about on the radio around the time I turned six.

I remember my dad’s stereo in the den of our house and a record collection that seemed to be at least a thousand strong. Our house had a piano and a Wurlitzer electric piano, a bass guitar and an acoustic guitar, but I never saw my dad playing anything at home besides his records. Men of his time didn’t tend to take work home with them. In that way, he was definitely old school.

Even though, on paper, it might seem that I have followed in my father’s footsteps, my place in the music business is almost on an opposite end of the spectrum. I play in a touring band that performs our own songs, many of which I write. I play one hundred or so shows a year in multiple continents and have done so for a couple of decades now.

My dad, on the other hand, went to work every day at the same studio, sat in the same chair, and played bass on other people’s songs for whatever artist came to town to hire him to do so. He got paid by the hour, usually something on the union scale. He played on many songs that sold in the millions of copies, but he almost never got “points” or a profit share of those hits. “I’ll Take You There” was a massive hit record and has since been used in movies and television commercials, but Dad once figured out that he’d been paid less than $2,000 total for his part—the most recognizable instrumental part of the song and one of the most beloved bass parts in modern music. Such is the life of a session player.

In the second grade, I was classmates with the son of one of my dad’s partners. Dale and I were best friends that year. I can remember him standing up before the class in show-and-tell and telling everyone that his father was the greatest drummer in the world. His father, Roger Hawkins, is indeed widely considered one of the finest drummers of all time. In addition to the hits he played on with my father, he also played on “When a Man Loves a Woman” recorded by Percy Sledge and “Respect” recorded by Aretha Franklin. Jerry Wexler, who discovered Ray Charles and was responsible for naming the “Rhythm and Blues” chart, shared Dale’s assessment of Roger’s drumming.

Unfortunately, Dale’s proclamation led to a good pummeling on the playground, and I made a note to myself that I wouldn’t talk about my dad’s occupation at Harlan Elementary School.

Photo courtesy Patterson Hood

Photo courtesy Patterson Hood

My hometown was the kind of deeply conservative place where, upon meeting someone new, often the first question asked was, “What church do you go to?” Most of my classmates had parents significantly older than mine who were culturally of a very different time and place. To all but my very best friends, what my dad did was a secret, best left unsaid.

Not that I knew much about it. I’d occasionally get little hints of who was in town, usually from my mom, but my dad shared few details about his work and the things that were going on at the studio. I can count on my hands the number of days I spent over there during my childhood. There were memorable exceptions. Linda Ronstadt recorded part of her self-titled solo album in Muscle Shoals and ended up coming over to the house one evening. She and my mom hit it off and stayed in touch for many years, including when she was one of the biggest stars in the world. (I came home from sixth grade one afternoon to find Linda sitting in our den, drinking beer with my mom.) When Bob Dylan came to town (the first time) I had a playdate with his son Jesse, who was probably about seven. Another time, my family had dinner with Bob Seger, who recorded many of his biggest hits with my dad and my dad’s partners. Cat Stevens once came by the house to pick up something from my dad.

As I got older, I became obsessed with music, rock & roll in particular, and I wanted to find out as much as I possibly could about this secret world that was happening right under my town’s nose. I began hanging out at the two local record stores all I could, endearing myself to the clerks there with my precocious thirst for musical knowledge. I would pocket my lunch money every week and do odd jobs around my uncle’s farm to get the latest releases from Elton John, Pink Floyd, Led Zeppelin, and Todd Rundgren. I had well over a hundred albums before sixth grade and more than two hundred and fifty by the time I entered junior high.

The record store clerks were my true lifeline to all of what was happening. Two in particular became sort of professors in my own personal school of rock. Jay Leavitt ran the cool little record store in Muscle Shoals about a block from the original FAME Studios that saw the recording of the classic Aretha and Wilson Pickett sessions. Jay was the one who turned me on to the Rolling Stones and explained what a special occurrence it was having the biggest rock & roll band in the world record three songs—“Brown Sugar,” “Wild Horses,” and “You Gotta Move”—at my dad’s studio. Jay also introduced me to Bruce Springsteen and took me to my first R.E.M. concert. Now, he owns Deep Groove Records in Richmond, Virginia.

The other record store guy was Terrell Benton, who was an assistant manager at the Record Bar in the mall on the Florence side of the Tennessee River. Terrell hired me to work at the store for my first job, and he exposed me to more musicians than I can count. He currently works as a tour guide at the old Muscle Shoals Sound Studio that has recently been renovated and reopened. All these years later, I still count Jay and Terrell among my closest friends.

My dad was never rich from his work as a session player, but we were comfortably upper-middle-class in a blue-collar town with a struggling economy. We lived in a neighborhood of older families, so I didn’t have many kids my age to play with on my street. At school, I was far more interested in writing my songs than participating in sports, so I was frequently bullied by the other kids. By high school I had found close friends and I also grew six inches in one summer, so the bullying stopped. We built a house out on Shoals Creek (also known as Shoal Creek), and my high school years were generally fun.

As tensions from the civil rights era calmed down, my dad’s work became less secretive, although I think most of the townsfolk were still somewhat oblivious to it all. Q107 might mention that a song they played was recorded there, but I’m not sure that actually registered with most of the people listening in their cars on their way to work, going about their lives. This probably explains how people as world famous as Mick Jagger, Bob Dylan, or Rod Stewart could stay at our local Holiday Inn and slip in and out basically undetected.

In 1982, the same month that I graduated from Coffee High School, the Ford plant announced that it would be closing. This began a domino effect that wrecked our hometown economy so bad that it has taken decades for it to rebuild. At about the same time, trends in music changed enough to essentially shut down the majority of our local recording scene. Many of the top session players moved north to Nashville or west to L.A. seeking greener pastures and better gigs. My dad was one of the holdouts who stayed behind to try to keep it going in Muscle Shoals.

By the time I dropped out of college and began playing full time in my own band, the recording scene at home was dying off. As a dry county, we never had a live music scene other than a few cover bands playing Top 40 or country hits at one of the rough-and-tumble bars up at the Tennessee state line. When voters finally approved legal liquor sales, I had visions of a live music scene starting up like the celebrated one in Athens, Georgia, that was spawning bands like R.E.M. and the B-52’s. Instead, we basically just got the same bars from the state line opening up in town. It was a dismal place to try to operate a punk band that only played the songs I was writing.

I moved away in the early ’90s, eventually settling in Athens, where I was able to form the band that I still play in today. More and more young people left for better opportunities elsewhere. My dad and the other holdouts who refused to move away stayed on, doing the best they could amongst fewer and fewer bookings.

A few years ago, a couple of filmmakers, Greg Camalier and Stephen Badger, made Muscle Shoals, a documentary about the musical miracles that occurred there. It was a critical and commercial success and helped spark a renaissance of interest in this unique music scene. The film release coincided with a loosening up of restrictions from the local governments that enabled more new local music venues to exist.

Downtown Florence, which had been fast becoming a ghost town in my youth, is beautiful and revitalized. More and more young people are forming bands and have a sense of pride in my hometown—one I never could have imagined growing up. In 2015, Lincoln Center hosted a Muscle Shoals tribute show that drew thousands of fans.

My dad turned 77 this September. He is thankfully in great health and still plays at a level comparable to his prime. He was never a fancy type of player, he didn’t “solo” or “thump” like some of his more flashy peers from the funk era. His signature is far more subtle, a matter of tone, of which he is considered a master, a melodicism in his playing that combines with a sort of minimalism to give him his unique and special sound. His Muscle Shoals sound.

I never played music with my father growing up. Whether it was a form of rebellion or just the times I came of age in, I gravitated toward a more unhinged and less disciplined sound in my own music. My early years as a player were spent trying to replicate a sound I heard in my head and to play the songs I was writing, and my dad often thought I was misguided in my early attempts at being a professional musician. Even though we both have the same basic occupation, we’ve always been on very different sides of it, and it wasn’t until much later that we began to bridge that gap musically.

In more recent years, my dad has played on two of my solo albums and has sat in with my band on stage in some wonderful venues, including the legendary Fox Theatre in Atlanta. I played with my dad at premieres of the Muscle Shoals documentary in New York City and Seattle as well as the Muscle Shoals tribute at Lincoln Center in 2015. We also formed a band called Dickinsons + Hoods with legendary producer/keyboardist Jim Dickinson and his sons Luther and Cody (of the acclaimed and wonderful band North Mississippi Allstars) back in 2007. Jim passed away before we could complete the album we started, but last year we finally completed tracking it and hope to put it out in the next year.

Both FAME and the original Muscle Shoals Sound Studio are open for recording and as tourist destinations, complete with guides. The past few years have seen thousands of visitors from nearly every continent touring those tiny studios. With their mid-century furnishings and accompanying color schemes, they still look exactly as they did in the late ’60s. And a new generation of musicians from the surrounding area is coming up—artists like Jason Isbell, Alabama Shakes, Dylan Leblanc, and the Secret Sisters, as well as my own band Drive-By Truckers. I suspect there will be more to come, all of us staking our own claims to musical immortality.

Stream Patterson Hood’s playlist for the Oxford American:

Enjoy this story? Subscribe to the Oxford American.