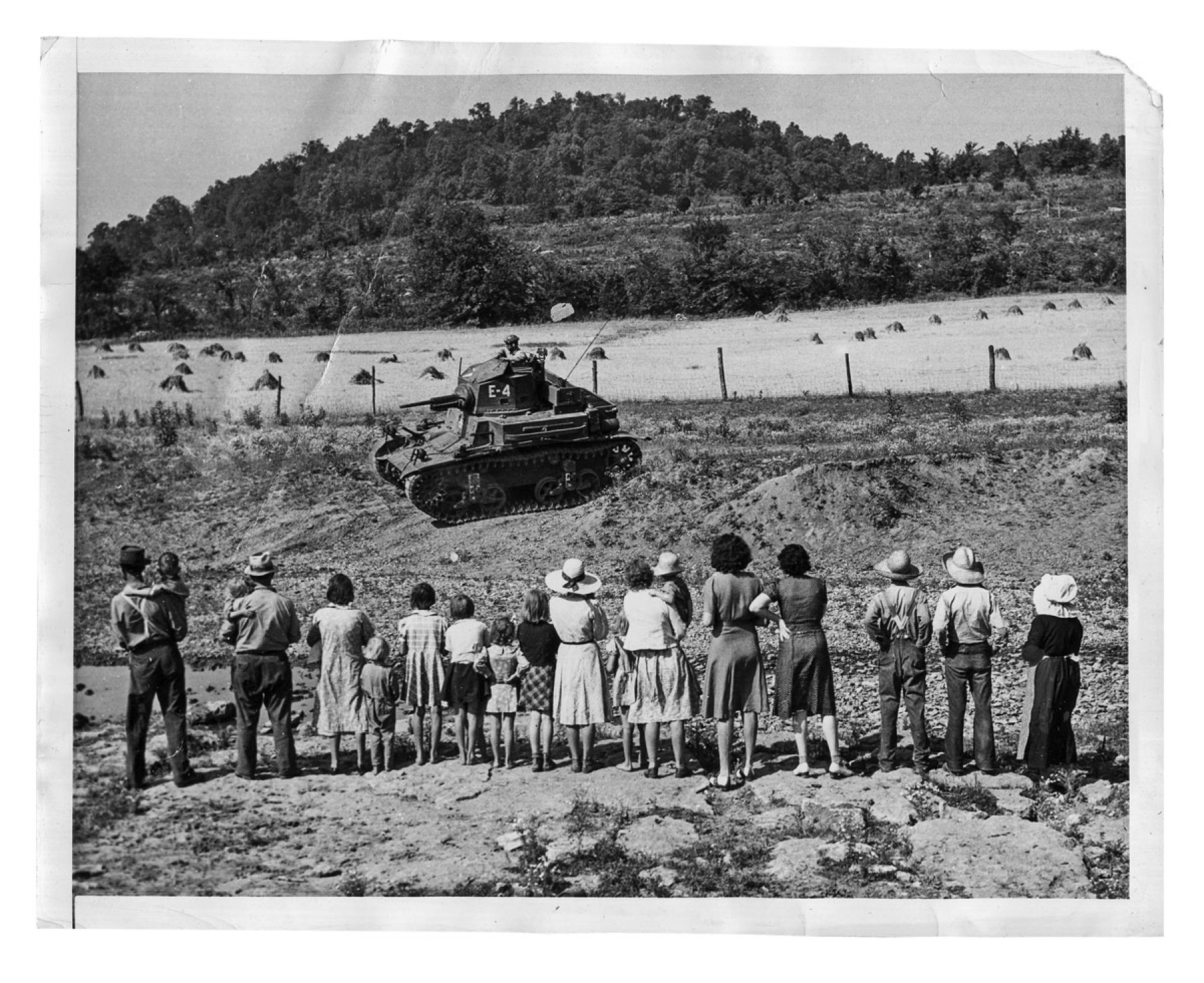

“Tennessee hillfolk are getting quite a ‘bang’ out of the strange doings of those soldiers from the flatlands of Fort Benning, Ga. . . . watching a tank of the Second Armored division do its stuff in a field.” Photo created by ACME, June 17, 1941. Courtesy the Tennessee Maneuvers Collection at the Albert Gore Research Center, Middle Tennessee State University, Murfreesboro

A Pleasant Catastrophe

By Rachael Maddux

All so-called grownups carry around with them worn remnants of their most beloved childhood delusions. So all the times my grandmother claimed to remember standing on her family’s front porch and watching General George S. Patton’s tanks roll by, I assumed she was mistaken.

She lived near Chestnut Mound, Tennessee, during World War II—a farming community 60 miles east of Nashville, and quite a few miles west of anywhere Old Blood and Guts’ troops saw action. She was ten years old when the U.S. entered the war, so I figured she was jumbling together an assortment of early memories—newsreels from the front lines, a funeral procession, a strange old dream—into something more fantastical than the sum of its parts.

I was in my thirties and she was in her eighties before the story hit me at such an angle that I considered she might not be wrong. We were on the phone one afternoon and she was telling me about her old house, how the bungalow sat right on the main road through town so you could stand on that porch and see everyone coming and going, by foot or tractor or truck. Or by tank.

The troops were there for training, she said, and they marched all around and sometimes slept in the fields and they weren’t supposed to but sometimes they came over for Sunday dinner, and they were in Tennessee because there was lots of wide-open country and Patton knew the land looked like where they’d be fighting in Germany and Belgium and France.

I heard that about the land and snapped back to a memory of my own: spring break, junior year of college, pressing my face to the window of a bus heading from Lyon to Nîmes, wondering if it was homesickness or actual geography that made the passing landscape remind me of my family’s many drives between our house in Chattanooga and my father’s hometown on the Cumberland Plateau.

I remembered that patchwork of fields and fencerows giving way to rocky riverbeds and rumpling up into old green mountains, and I realized what my grandmother said had to be true. I’d accumulated just enough of my own details of the world to match this handful she’d always been offering me.

But I didn’t know any more than that, and neither did she, just her slivers of it, by then seven decades past.

I asked my father, who was born in the 1950s, but he didn’t remember anything other than his mother’s offhand mentions over the years. A casual poll of fellow Tennesseans returned mostly shrugs, too.

Everyone knew about Oak Ridge, of course, the secretive home of the Manhattan Project, and some knew there’d been troops stationed out in Tullahoma and up at Fort Campbell. But Patton? Tanks? Farmyard bivouacs?

I didn’t even know what to call it, not until I dumped my accumulated handful of keywords into the maw of Google. Then there it was, sounding for all the world like a long-forgotten dance craze: the Tennessee Maneuvers.

The short version of the story is this: In the first half of the 1940s, Tennessee hosted more than one million members of the U.S. military as they readied themselves for war. Between summer of 1941 and spring of 1944, in particular, upwards of 850,000 soldiers of the Second Army of the United States of America funneled into the state’s hilly midsection to learn how to fight. This wasn’t basic training—this was the real thing. Or as real as it could get until the real real thing.

For a while, the short version is all I had. Though the existence of the Tennessee Maneuvers had stumped me, my family, and everyone I ever asked about them, I was still surprised to learn that not much has been written on the subject.

There are plenty of contemporaneous accounts, published everywhere from the tiny Putnam County Herald to the New York Times. But it seems to have been lost in the wider swirl of all the war’s griefs and triumphs. In 1956, Eugene Sloan, who covered the maneuvers for the Nashville Banner with the tenacity of a frontline correspondent, called them “another of the ‘dropped stitches’ of Tennessee history.”

Since then, what’s been written about the maneuvers would fill a milk crate with room to spare (perhaps for a few of the dozen books exploring the intrigues of Atomic City, or one of a hundred thick tomes about Patton’s battlefield exploits). I’ve found a smattering of academic journal articles, most from the 1990s; one 2007 report from the Tennessee Department of Environment and Conservation’s Division of Archaeology; a single book, In the Presence of Soldiers, self-published in 2010 by a military history enthusiast named Woody McMillin; one 2014 master’s thesis by a graduate student at East Tennessee State University; and not much more.

Most writers have treated the maneuvers as primarily a military phenomenon—but even within the vast world of World War II scholarship (according to that ETSU master’s thesis) they haven’t received their due. But my interest—in the beginning, at least—was entirely personal. I wanted to understand something about the world my grandmother grew up in. And I wanted to understand how the residents of Middle Tennessee—who I’ve long thought of, for better or worse, as “my people”—handled what seemed to me like an utterly bizarre and destabilizing event: a real war raging abroad, and a fake war raging in their backyards.

But the more I read and the closer I got to the bottom of that crate, the more I was distracted by the story of the story itself.

Soldiers in downtown Shelbyville during World War II maneuvers. Courtesy the National Archives

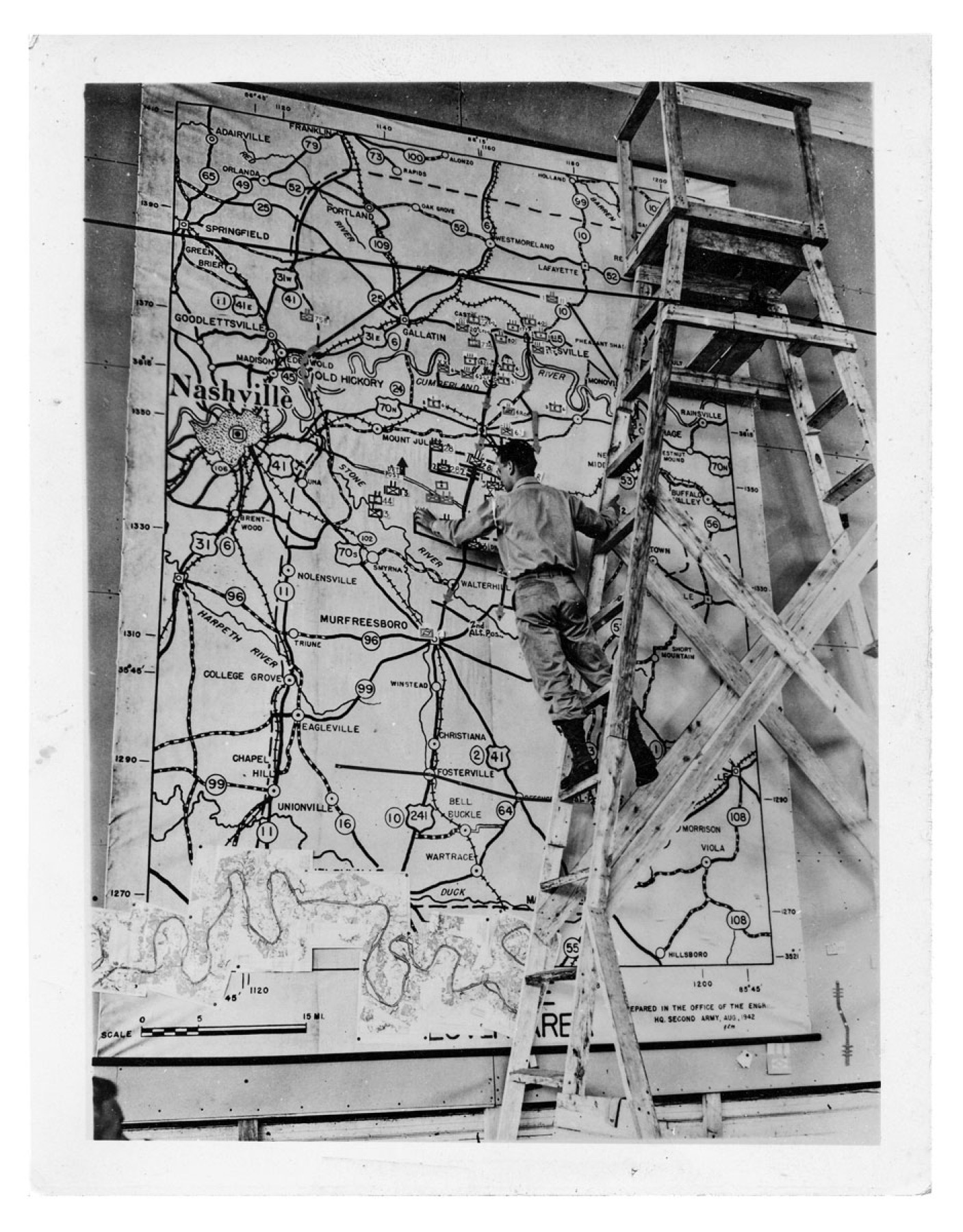

Soldier with large map of Tennessee maneuver area, 1941; Courtesy the Albert Gore Research Center, Middle Tennessee State University, Murfreesboro

Despite my own inclinations, this is a war story—so let’s start there.

After the end of the First World War, the United States military fell into a slump. In particular, the Second Army—a major fighting force during the war—became “largely a paper army,” existing only in theory outside occasional training exercises, according to an Army Ground Forces Study published in 1946. But once the Selective Service Act of 1940 opened up the country’s first peacetime draft, those paper ranks began to grow by the ream. Meanwhile, other folks (namely, Adolf Hitler) had figured out some new ways of killing people (namely, using machine guns and tanks) not in theory, but quite literally and brutally all across Europe. So the U.S. had a bunch of soldiers who needed to learn how to be soldiers, good ones, and fast.

There were other maneuvers throughout the war: earlier in Louisiana, and later throughout the Carolinas, along the California-Arizona border, and in West Virginia. But Tennessee’s were the longest running, nine phases over three years.

The Army staged the first round in June 1941—six months before Pearl Harbor, when the United States was technically still neutral but preparing in earnest to be otherwise—with action mostly confined to Rutherford, Bedford, and Coffee counties. By the final round, in early 1944, the maneuvers had sprawled across 21 of the state’s 95 counties, more than 600 square miles, from the southern border with Alabama up the Cumberland Plateau to Kentucky.

“These maneuvers are a dress rehearsal for a grim and dirty business,” Lieutenant General Lesley J. McNair, commander of the Army Ground Forces, said at a 1943 press conference. “When the chips are down, the lessons learned in Middle Tennessee will make the going easier from the beaches to Berlin.”

The Second Army prepared for the figurative theatre of war with literal theatre. The troops marched through dust and rain and mud, navigated unfamiliar terrain, set up and struck camp, dug latrines, ran communications lines, managed supply lines. They learned how to give and follow orders. They battled through “problems” set by Army officers: Red army versus Blue, with real weapons and fake ammunition—guns loaded with blanks, grenades and bombs packed with flour. They captured and released prisoners of war. They tested new military strategies and technologies, like the use of paratroopers and gliders and Patton’s armored divisions, even a new type of all-terrain vehicle, the jauntily named Blitz Buggy, later known as just a Jeep. Umpires watched from the sidelines, taking notes and declaiming victors.

The point was to mitigate the actual war’s body count, but the war games had deaths of their own. Of the 850,000 troops on maneuvers, two hundred and sixty-eight died, including 62 in vehicle accidents and 21 men who drowned when their assault boat capsized during a training run across the Cumberland River, a stand-in for the Rhine.

In June 1942, Governor Prentice Cooper granted the U.S. Army rights to train in the area for five more years. But it all began to wind down in early 1944, as most of the Second Army troops in Tennessee were moved out to the European front for D-Day and the war’s final push into Germany. There they made good on McNair’s press conference promise—mere weeks before the general himself was killed by friendly fire in France.

“It was the Fourth armored, that even in Middle Tennessee were named the ‘break through boys,’ that . . . spearheaded the Third Army’s drive to within 140 miles of Berlin,” wrote the Nashville Banner’s Gene H. Sloan. “The true worth of maneuver training will never be evaluated in the number of lives saved, the months the war was shortened, or the money and materials conserved.”

And all of this—the marching, the battles, the bivouacs, the deaths—happened in, on, and around the highways, bridges, rivers, farmyards, backyards, college campuses, and public squares of cities, towns, and hamlets occupied by roughly 404,000 Tennesseans, outnumbered by soldiers two to one, who had little choice but to stand and watch the fledgling war machine roll by.

Over the last eight decades, the prevailing narrative of the maneuvers—scant as it is—has held that the people of Middle Tennessee embraced the chaos with uncommon grace and aplomb.

“Everyone, no matter how humble, did their part in doing what was right for our soldiers,” June Oakley Gonzalez—12 years old and living in Lebanon, Tennessee, when the war began—told the Tennessee Historical Quarterly in 1992. “We would be walking to school and bullets, blanks of course, would be flying everywhere. So many empty shells we would gather.”

By all accounts, the maneuvers’ disruptions to daily life were significant. Residents were startled by battles crossing their backyards at midnight (featuring increasingly realistic sound effects) and by stealthier troops shimmying through their shrubbery in broad daylight. Some mornings, they found men stretched out asleep on sidewalks, park benches, cemetery lawns, and inside unlocked cars. Traffic jams—nearly unheard of before—became commonplace. And ten civilians died from injuries sustained in accidents involving military equipment in the maneuvers area, many of them wrecks caused by night-driving in blackout conditions.

The material damage was significant, too, especially in farming communities. Livestock escaped through busted gates and fences. Precious topsoil was decimated, orchards wounded. One man reported that soldiers stole 275 watermelons from his garden patch. During the first round of maneuvers, while cruising through downtown Bell Buckle, one of Patton’s tanks crashed into city hall. In Wilson County, Woody McMillin writes in In the Presence of Soldiers, “schools had to be closed, and mail routes and milk runs stopped because of heavy damage caused by tanks and military vehicles.” All of this was compounded by baseline wartime privations like rationing, depleted education funding, and increasingly inaccessible healthcare, especially in rural areas, as more doctors were called into service.

In the months after the maneuvers ended, the federal government paid $2,600,000 in private property damage claims and $2 million more to local governments for municipal repairs—though one estimate by Governor Cooper put the total at $4 million for ruined roads alone. (Adjusted for inflation, that’s over $75 million in 2021 dollars.)

Before the maneuvers began, Army officials did ask for landowners’ permission to access their private property, and most acquiesced. “This permission was a mere formality though, as one Wilson County farmer would find out,” Benjamin Nance wrote in the TDEC’s Division of Archaeology’s 2007 report. “He did not want troops on his farm [so] he put up signs that said ARMY KEEP OUT. According to a current resident of the area, that farmer suffered the worst fence damage of anyone in the vicinity.” McMillin’s book notes a few similar examples. But no names are mentioned, no specifics, no more space made for the story than necessary.

The narrative of the maneuvers favors a different sort of resistance. “They tore up our woods really bad by digging foxholes and carving on the trees. They even had tanks in the woods,” Lucille Hager Hall, a wartime resident of Davidson County, told McMillin. “When the government came to settle for the damages, Papa wouldn’t take a penny. We sure could have used the money.”

Many locals seem to have been generous to a fault—to their own detriment, and that of the troops. Army officials were constantly reminding civilians that the men were supposed to be learning how to be self-sufficient in a war zone. That meant no giving directions, and no feeding the soldiers. “Still, many were unable to watch men go hours without eating, and some trekked into combat zones with ham and biscuits, iced tea, and other staples,” McMillin writes. “Others invited men into their homes or onto their porches for a surreptitious supply of fried chicken.”

Ernest Weatherly, quoted in McMillin’s book, recalled his mother feeding soldiers on the regular at their home in Lebanon. They always wanted to pay, and she always refused—rationing be damned. When they started leaving dollar bills under their plates, she started checking under their plates before they left and returning the money. Finally, the men started paying her son directly with cans of gasoline for the family car.

“The people of Tennessee seemed to be thrilled, cooperative, and proud of our army,” Major Norris H. Perkins wrote in his 1988 memoir, Roll Again Second Armored. “Motorists threw candy and food to the men. Many of the women were quite emotional and exchanged notes and addresses with us.”

In 2003, my grandmother’s cousin, Nancy Jarrell, a teenager during the war, recalled the final days of the maneuvers in a newsletter published by Cookeville’s Friends of the Depot organization. “Thousands of little connections had been made: a button sewn on, a letter written, a phone call made, a ping-pong match won, a birthday cake baked, a few hundred miles stomped at the Savoy, a hand held, a kiss given and received,” she wrote. “These were not just troops—they were young men in our lives who were about to become memories.”

Memories are subject to all sorts of distortion, of course, especially after more than a few decades. But the locals’ expansive unflappability was reflected in contemporaneous press coverage too.

“I can imagine what some city dweller would say if you so much as drove a Jeep on his lawn. And if you were to step on his flower bed!” Major General W. A. Burress remarked to the Nashville Banner’s Sloan in 1944. “Here these folks are as courteous and friendly as if you were doing them a favor instead of them catching hell.” At the time of his interview, Burress and another general were helping the son of a local farmer hang a 500-pound sow to be butchered, so apparently the fond feelings went both ways.

“To their everlasting credit, [the locals] have neither complained nor profiteered,” New York Times correspondent Hilton H. Railey wrote from Manchester during the maneuvers. “Taken by and large, it has been a pleasant catastrophe.”

Residents were startled by battles crossing their backyards at midnight (featuring increasingly realistic sound effects) and by stealthier troops shimmying through their shrubbery in broad daylight.

I found these accounts charming, at first, and then entirely alienating.

I began researching the maneuvers in earnest in the spring of 2020, as the coronavirus pandemic was first ripping across the planet. I often found myself toggling between these accounts of homey bonhomie and breaking news stories about innovations in wanton cruelty, like the stranger who walked up to a family, coughed on them, and ran away laughing. People I knew were doing whatever they considered “their part”—canceling travel, wearing masks, expunging their guilt over the exploitative gig economy by over-tipping delivery drivers—but they weren’t throwing themselves into the endeavor with anything resembling good cheer. Everyone was just doing what they needed to get by, and feeling all sorts of ways about it—angry and tired and confused and tired and abandoned and ambivalent and tired.

Over the summer, I watched through my screens as the streets of America filled with protestors. Most of them were demanding that Black people be treated—by police, by the government, by anyone—like actual human beings. Others, with their naked white faces, were appalled that they were being asked to consider the humanity of anyone other than themselves.

Meanwhile, Middle Tennessee in the 1940s—despite the immediate and existential demands of war—seemed to have been an orgy of goodwill and home cookin’. I began to suspect that the civilians who endured the maneuvers, as many have suggested of that generation of Americans overall, were somehow a superior varietal of human being.

Then one day a friend half joked, about her toddler, “I’m glad she won’t remember much of 2020, but I’m already dreading what she’ll be taught about this in school.”

And I remembered that history always begins as a collection of individual realities. And no moment is ever just one moment. And what comes next, all the storytelling, all the meaning-making, is a power struggle, and it never truly ends.

The more I read about the maneuvers, the more I suspected that there was a more complex story struggling to breathe somewhere under the smothering blankets of patriotic romanticism and wartime nostalgia.

I kept thinking of one passage from In the Presence of Soldiers: “Across much of middle Tennessee for most of the war, soldiers wearing the distinctive 2nd Army shoulder patch, the numeral 2 in red and white, would become familiar symbols of military authority. Men wearing the embroidered emblem were recognized, by soldiers and civilians alike, as all-powerful leaders whose orders were to be followed without question.”

I took that and added it to what I know about the historic, systemic power imbalances between men and women, and between white people and Black people. I thought about rape and harassment. I thought about lynchings. I thought about all the nasty little feelings that can crowd the mind when somebody’s in charge and it’s not you.

But I’m not a historian, just a nosy writer with internet-searching skills honed in the days of Ask Jeeves.

For a professional opinion, I called Sarah Calise, an archivist at Middle Tennessee State University’s Albert Gore Research Center, which is home to a huge collection of documents, oral histories, and ephemera from the World War II years in Middle Tennessee, including the maneuvers.

“My frustrations are yours, too,” she told me more than once.

The Gore Center’s archives house a number of oral history interviews with people who lived through the maneuvers, she said, but it’s mostly white men and women talking to and about white men and women. Their recollections, like the ones I came across in my reading, seem to be largely fond ones. Most interviewees were children or teenagers during the war, giving their memories a softer focus—blurred by time and other forces.

“I wonder, honestly, how much of the romanticism that we have around World War II has shaped their own memory of how they’re supposed to even speak about this time,” Calise said. “It’s almost sacrilegious to say otherwise, to say that there were bad things that were happening. . . . But for a select group of people, it wasn’t the best time.”

She pointed me towards the work of historic preservationist Kelsey Lamkin, whose graduate work at MTSU focused on the sexualization of Nashville’s public sphere during World War II.

In particular, Lamkin studied the response to the city’s wartime venereal disease epidemic, which was widespread enough that Tennessee became one of two states to invoke the May Act—a 1941 piece of federal legislation that gave the U.S. government power to enforce local anti-prostitution laws in the interest of protecting its military “within such reasonable distance of any military or naval camp, station, fort, post, yard, base, cantonment, training or mobilization place.”

In Tennessee, that included the entire maneuvers area, which in effect meant every business, school, and home within those 600 square miles—even vehicles just passing through—could be considered a potentially nefarious locale. A woman walking down the street near a known brothel, or simply hailing a taxi for herself, was enough to arouse authorities’ suspicion of prostitution—either “commercial” (sex for pay) or “clandestine” (sex with anyone other than your husband). Authorities subjected many of the women they arrested to additional indignities in the name of public health, including forced examination for venereal disease (and, if any was detected, compulsory treatment and quarantine). Meanwhile, the Army provided enlisted men a ration of six condoms per month.

I wasn’t able to find any first-hand accounts from women who were caught up in the May Act’s preposterous dragnet. In fact, I didn’t encounter any first-hand accounts from women who had anything less than delightful interactions with the 850,000 men who came through on maneuvers. But I wonder about those “all-powerful leaders whose orders were to be followed without question” and how they might have used—misused—their power. What did those women write in their diaries? What did they tell their mothers and their friends? What did they never, ever tell a soul?

“I need to know, but it’s just gone,” I lamented to Calise. “It’s this black box of history, and it’s killing me.”

“Yeah, it sucks,” she laughed. “Every day I’m annoyed by people in the past who didn’t do good historical recordings. If I had a time machine I’d go back and do so much archival work.”

As a historian, Calise’s main areas of focus are the Civil Rights and Black Power movements, in which Black veterans were major players. So she’s especially attuned to the presence—or absence—of Black soldiers’ stories in World War II narratives.

“It’s so weird what gets omitted,” she said. “McMillin does a whole page and a half on the barrage balloon battalion and never mentions that the 320th was an all African-American unit, and they were the only African-American unit to participate in the Normandy invasion. Direct connections from Normandy to Tennessee, and no one brings it up.”

Even in the Gore Center’s archives, she’s found very few accounts of Black soldiers during the maneuvers. I struck out at the Tennessee State Museum and the Tennessee State Archives, too.

I don’t know how many of the 850,000 soldiers that trained during the maneuvers were Black—but Black soldiers made up about six percent of the armed forces overall. I don’t know how many Black soldiers came to the maneuvers area from outside the South—but I do know many Black families had taken or would take great pains to extract themselves from the region and its absurdly oppressive Jim Crow regime during the ongoing Great Migration.

In Tennessee, Black soldiers were members of a segregated Army training in a segregated state, a confluence of inequalities. But in everything I’ve read about the maneuvers, the element of race has been minimized, elided, or disregarded entirely. Whenever the authors of these accounts mention race, it’s usually in the context of social events—dances and holiday parties, always segregated—but with little mention of the oppressive laws and social mentality that necessitated such accommodations.

A few pieces do note that the maneuvers trained the 758th tank battalion (later the 761st tank battalion) which, in France in November 1944, became the first Black armored unit to see combat in World War II. Nicknamed the Black Panthers, they later fought in the Battle of the Bulge with General Patton, who told them, “I don’t care what color you are as long as you go up there and kill those Kraut sons-of-bitches.” Patton may not have cared, but their skin color mattered before the battle and it mattered after, too.

According to the 1940 U.S. Census, of the roughly 404,000 residents of the 21 counties, about 45,000 of them were Black. But in everything I’ve read about the maneuvers, I can’t recall a single Black civilian—or soldier, for that matter—being mentioned by their name.

And I found nothing about how they might’ve responded to the maneuvers and its mass influx of white soldiers. They may have been firing blanks, but their uniforms marked them as agents of the state that had been dehumanizing and disenfranchising Black people since before its inception.

All-powerful leaders whose orders were to be followed without question.

There’s very little about race in the stories of the Tennessee Maneuvers, but there are plenty of jokes about the “second Yankee invasion.” The year 1861 was as far from 1941 as 1941 is from 2021, and a few Confederates still clung to life in Middle Tennessee. Frank Ross, aged 99, got to ride in a Jeep. A man apparently known to everyone as “Uncle” Polk Sagely, 95, was allowed to admire some of the newfangled weaponry. Of one anti-tank gun, he said, “That little cannon wouldn’t hurt a flea.” Shown a 600-shot Browning automatic rifle, he said, “It’s too bad we didn’t have them in ’63.”

Soon after, in nearby Tullahoma, the U.S. Army would imprison several hundred Japanese, Italian, and German American civilians—so called “alien enemies”—in barracks at what had once been called Camp Peay, after the first Tennessee governor to die in office, but which had recently been renamed Camp Forrest, as in Nathan Bedford, Confederate general and first Grand Wizard of the KKK.

There are so many stories of the Tennessee Maneuvers that no one will ever know. There are so many stories that were never told in the first place. But the stories we do know tell a story of their own.

All so-called grownups carry around remnants of their most beloved childhood delusions, and we hold on to them so tightly—maybe because we know they’re only stories. Hold them tight enough for long enough and all the rough edges wear away. They go smooth, they go flat. We forget whatever they started as—all the many facets, the true texture—and impose upon them instead a mis-remembered ideal of what we wish they used to be.

I keep thinking about what started all of this, my grandmother’s memory of standing on her porch watching Patton’s troops roll by. I was mistaken in thinking she was mistaken—at least about where she stood and what she saw. The matter of why she saw it, though, still isn’t clear.

My grandmother told me, without a note of skepticism, that Patton picked Middle Tennessee for training because he knew the land looked like the terrain in Europe where the men would be sent to fight. Reading about the maneuvers, I encountered that same explanation over and over again.

At first, I didn’t quite buy it—like, how would he know? Then I read that he’d grown up visiting his own grandmother in Watertown, halfway between Nashville and Cookeville. This seemed right to me. I liked the idea that the landscape might have pressed itself into this famously hard man the same way it did to me. I liked the idea that, when he stood and surveyed the battlefields of France and Belgium and Germany—where, even amid so much death and destruction, the patchwork of fields still went down to rocky riverbeds and up to old green mountains—maybe for a moment he felt homesick too.

The useful similarity of the Middle Tennessee terrain was noted, at the time, by everyone from the op-ed writers of the Cookeville Herald to Lieutenant General Lloyd Fredendall, commander of the Second Army. Other maneuvers locations were chosen for their resemblance to eventual battlefields too, with the California desert standing in for North Africa and the mountains of West Virginia for the mountains of Central Europe. But I haven’t been able to find a single quote or source attributing the choice of Tennessee to Patton himself. It seems more likely that it was determined by a confluence of factors, political and bureaucratic, and by nobody in particular. A less exciting explanation, for sure. Barely an explanation at all.

My grandmother died in 2016. But when I think about trying to correct her on this point—well, I doubt she would’ve believed me. I think it was important to her to believe that Patton hand-picked Tennessee.

Just like it’s important to eighty years of historians to believe that the people of Middle Tennessee responded to the maneuvers with nothing but open fields and open hearts. Just like it’s important to white America to believe that we’re always the good guys—good to the world and good to ourselves.

We carry these remnants with us—and we have for so long, and so closely, we’ve forgotten to feel the weight. But they’re still there, always there, just waiting for the moment when the pressure changes, the grip shifts, and they can finally start to work free.