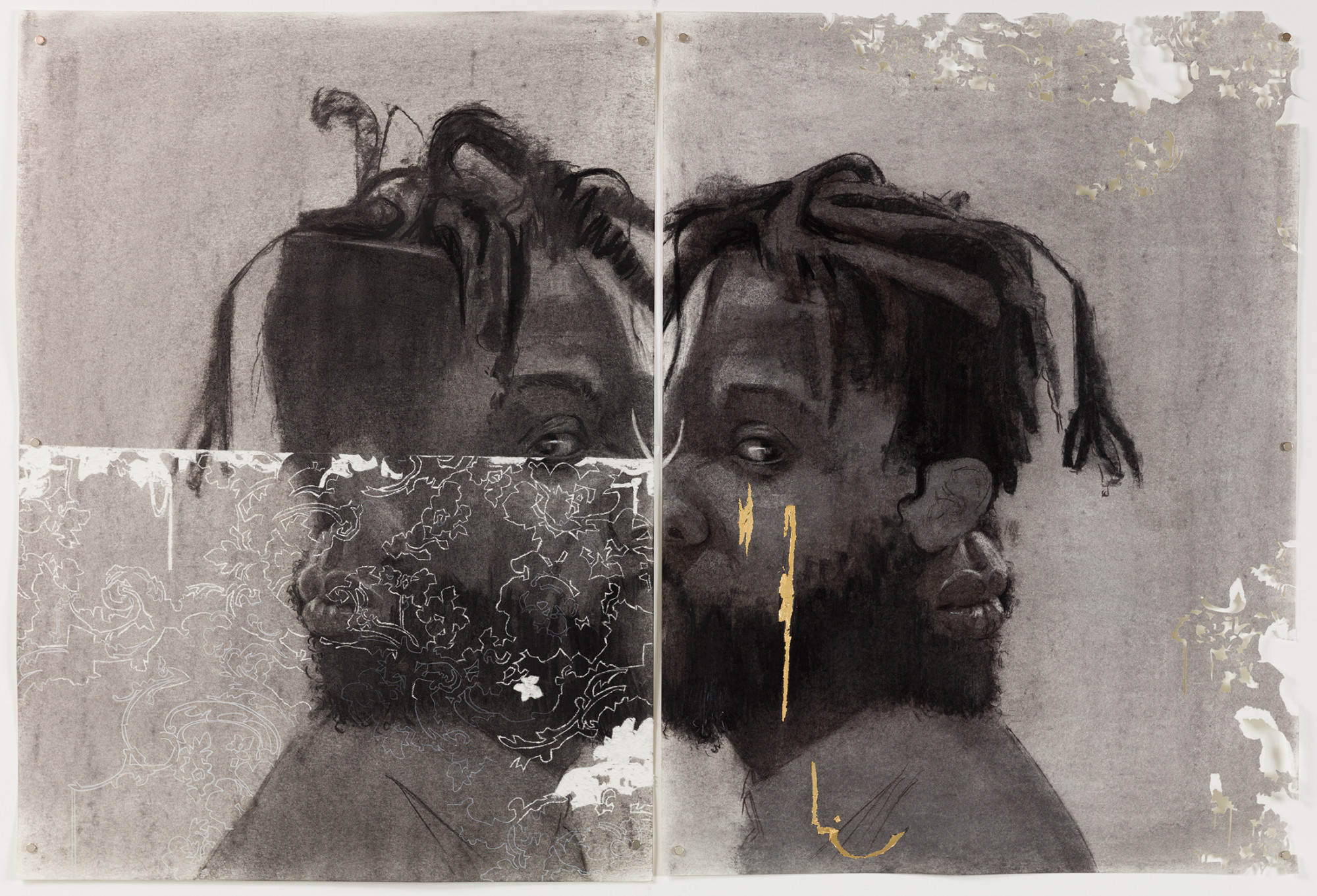

Du Boys (1), 2020, charcoal and gold leaf on paper by Cosmo Whyte. Courtesy the artist and Anat Ebgi, Los Angeles

Madness in the Cupboards

billy woods’s gripping rhymes elevate the ordinary

By Marcus J. Moore

When billy woods was nine years old, he wrote a short story for a class project that he was really proud of. Sure it was “a Stephen King rip-off,” the rapper admits, but the teacher loved it. She gave it a gold star and everything. He showed the story to his mother, an English literature professor, and learned a quick lesson in humility.

“She read it and was like, ‘I think it’s cliché,’” woods deadpanned during lunch this past September in Williamsburg, Brooklyn. “And I remember being really like, ‘Oh wow,’ like a little hurt at the time.”

The short story featured a divorced detective, because, as woods put it, “I watched a million movies in the ’80s about cops whose marriages fell apart because they were so into their job.” Then, for whatever reason, there was a child who got lost in a haunted house. It was all over the place conceptually, foreshadowing the broad lyrical approach that would make woods one of hip-hop’s most innovative narrators thirty years later. His mother’s lukewarm reception taught him to avoid tropes and platitudes.

“At an early age, I learned to think critically about the way I was writing,” said woods, now in his mid-forties. “I’m always thinking about how to dig towards some sort of real truth in life, to convey something that I feel or see. I’ve always wanted to find ways to say something that is true, meaningful, or funny—or all three.”

Listening to woods talk about his life and music, I can see why he’s adored by hordes of fans throughout the world. Sporting long dreadlocks and dressed casually in a t-shirt and shorts, he’s laid-back and unassuming, and unpacks his personal life and career with remarkable ease and affability. My questions were sometimes interrupted by his own inquiries, about my or my wife’s upbringing and the time we spent living in Nairobi, Kenya: woods spent his formative years in Zimbabwe, so this section of my biography seemed to be of particular interest.

Across more than a dozen critically acclaimed projects—including some as a solo artist, some alongside producers Kenny Segal and Messiah Musik and poet Moor Mother, and some as one half of Armand Hammer with the Brooklyn rapper Elucid—woods has garnered a cult-like following in so-called underground hip-hop, a steady force gathering steam with each release, guest verse, and live performance. woods is a throwback, conjuring the 1990s and baggy jeans and oversized designer hoodies, when New York groups like Wu-Tang Clan and Mobb Deep released music with decidedly dark concepts and lyrical complexity that took precedence over club-ready beats. There’s a pronounced grit to woods’s music: The instrumentals are often sullen and down-tempo, and woods—through a mix of regular, conversational tones and declarative yelling—spits tightly coiled lattices made for deep listening. woods isn’t the rapper you let simmer in the background; you have to lean into his vivid prose. Though it’s become easy for critics to call his music dystopian, there’s plenty of joy and candor between the notes. When, on the song “spider hole,” he declares, “I don’t wanna go see Nas with an orchestra at Carnegie Hall,” he’s speaking to a segment of New York City that doesn’t feel comfortable in the swanky Midtown Manhattan venue, to fans who’d rather celebrate the noted Queens rapper in a place more welcoming of hip-hop culture.

As for why woods has stylized his name in lowercase letters, a technique he started at the age of twenty-two, the motivation is still unclear. Over email, he said it’s “one of many noms de guerre that I had adopted for practical reasons,” then he decided to stick with it for the music. But that’s just woods being woods: As open as he can be about personal topics, he’d rather leave other details to mystery.

“woods is brilliant,” Elucid said in a telephone interview. “He can talk to you about such a wide range of things, and he has such knowledge and genuine interest in many different areas of life—from politics to barbecuing. He’s just a very interesting dude, and as a writer, he strives for a sense of honesty in his music. When you do that, you come out, the inside comes out, all those little things that make him cool come out in the lyrics.”

Church, the second of two albums that woods released in 2022, is a swift, thirty-seven-minute trek through his bicontinental upbringing and the beliefs shaping his perspective, all fueled by a hard-to-find strain of marijuana called “Church” that he smoked while writing the songs. Complex topics like religion, spirituality, and faith are examined in quick-witted barbs that land comically, like on the opening track, “Paraquat,” where woods calls out the hypocrisy of New York Black Muslims who preach the word of Allah while living immorally: “Brothers started on that Malachi Z., I said I eat pork / And besides, I don’t respect it / You out here smokin’ Newports, please man lemme eat my breakfast.” Then there’s a song like “Fever Grass,” a striking depiction of his childhood:

House of Hunger, cold stove, it’s madness in the cupboards

It’s no table manners at ya cousin’s, it’s humming microwave ovens

It’s auntie, bent back from the juggling

Moms would send me over there with somethin,’ mumblin’ about that deadbeat husband.

To me, it sounds like woods is talking about his aunt’s home. But truth and fiction are commingling, and there’s no telling if he’s discussing his own family unit or someone else’s. In the broader context, though, you find he’s echoing common family dynamics. Many of us have relatives with unruly houses and parents who beef with each other.

woods was born in Washington, D.C., and raised between Hyattsville, Maryland, and Zimbabwe in southern Africa, after it was separated from the white supremacist state of Rhodesia. His father worked as a professor at the University of Maryland, College Park and his mother at Howard University in Northwest D.C. The two met in New York City. In 1979, when the Lancaster House Agreement freed Zimbabwe from Rhodesia, his father—a Zimbabwe native who wrote, published, and fundraised in the country’s war for liberation—went back to southern Africa and worked in local government. But his mother, who is Jamaican, didn’t move there right away; she waited until the dust settled and decamped for Zimbabwe in 1981, when woods was five.

woods spent eight years in Zimbabwe, going to elementary school there. As an American with privilege, he said he felt like an outsider. A simple bicycle ride with friends became a lesson in race relations. “We go to this one [white] kid’s house to get some sodas or whatever,” he recalled. “When we’re at the gate, one of the little boys turns and says, ‘My father doesn’t let kaffirs in the house,’” referring to the ethnic slur derived from South Africa. “I don’t know if I even knew what that word meant yet.” The racist incident didn’t affect woods like it would have in the States. “It didn’t matter if this guy didn’t want me to come into his house,” he declared. “Their house wasn’t nicer than my house. The president is a Black person. The thought that a white Rhodesian thought he was better than me seemed comical.”

woods’s family moved back to Maryland in 1989, as Black communities were being ravaged by the ongoing proliferation of crack cocaine. Here, the racism was subtle, something woods wasn’t used to. “Things would happen and I’d think, ‘Did this happen because I’m Black? Did this person just not like me? Did I imagine the whole thing?’” woods said. “It was that constant having to guess, understand, and then also—for your own safety—moderate your response or what you’re going to do. It was a different world.”

woods references these cross-continental differences in his music, sometimes shouting out Zimbabwe in his lyrics. In turn, his rhymes have a global, educational perspective. While rappers like Tyler, the Creator and J. Cole reference foreign landscapes as a way to stunt on their peers, woods takes a scholarly approach, name-dropping the obscure landmarks and public figures that map his existence. It gives the music incredible texture; his writing captures the beauty, fortitude, and absurdity of the places he’s lived and things he’s seen. For a person who’s been here and there, his rhymes remain grounded in the constant ebb and flow of existence. Albums like Church, Aethiopes, and 2012’s History Will Absolve Me synthesize American pop culture, Black revolution, and heartfelt memoir all at the same time.

woods started rapping in 1998 when, upon moving to Harlem, he linked with a hip-hop collective called the Atoms Family that was co-founded by future indie rap stalwarts Vast Aire and Vordul Mega. He started hanging out with Mega, who encouraged woods to spit rhymes during freestyle cyphers. “This was the first time I’m seeing people do this and not just people on TV doing it,” he remembered. “And I’m like, ‘Oh, people just rap for real?’” He lived in Harlem for two years, then went back to D.C. and attended Howard University, where he started writing rhymes in earnest. By 2001, Aire and Mega started rapping as the duo Cannibal Ox, and released their debut album, The Cold Vein, to massive acclaim. That, coupled with the rise of New York underground rap, enticed woods to get serious about his craft. He moved back to New York thinking he’d have a chance to rap on one of Mega’s songs. Once that fell through, thanks to a shoddy studio session caused by Mega’s handlers, woods launched his own label—Backwoodz Studioz—which he still operates today.

“I walked out into pouring rain and caught the train home like, ‘I can’t ever be in that position again,’” woods said. “Because part of me was like, ‘Man, maybe I suck.’ Then I was like, ‘Nah, I’m not going for that. I just can’t be in that position again. I can’t.’”

His solo career began in 2002 when he met a producer with a studio in Westchester County. He’d go there for overnight stays and weekends, completing songs that would become Camouflage, his debut album, released a year later. Releasing the LP independently was done out of necessity. “It was just more of a lesson to me like, ‘Am I going to quit because these other people kind of flaked out or things fell apart?’” woods said. “And I was like, ‘Nah, I got to do it.’ I put it out myself, made the album artwork at Kinko’s.” He hit a stride in the early 2010s when critics took notice of the albums History Will Absolve Me and 2013’s Dour Candy, the latter praised by Pitchfork for its narrative arc and woods’s multi-layered lyrical technique. Also that year, he and Elucid released Race Music, their first album as Armand Hammer.

Elucid remembered being put off by woods’s flow initially. “I remember thinking, ‘This guy raps really offbeat,’” he said with a laugh. “His sense of rhythm was and is his own. I’m thinking he’s not doing it right, but then I keep listening. He finds these really interesting pockets. You interpret a song as one thing, but it’s really about the other thing and it was connected to this other story about his childhood. And he’s super adept at just being a captivating motherfucker.”

When I first heard woods, I was intrigued by the sense of wonder his music promotes. I found it accessible and challenging, serious yet whimsical. Surely it was riveting, but it was also confounding—tough to dissect, full of powerful one-liners that cut through the backing track. On Church’s “Pollo Rico,” he doesn’t just mention the hospital vending machine, he breaks down the snacks behind the glass. “D2 is the Cheetos,” he raps. Then on “Tabula Rasa,” from rapper Earl Sweatshirt’s 2022 album Sick!, he goes from sneaking liquor into the nightclub to cooking chicken and watching reruns in a dark room. His rhymes can seem over the top, yet they’re so vivid and confident that I can’t turn away. He makes the mundane sound fascinating.

The rapper/producer Quelle Chris, a frequent woods collaborator, likened woods to Gil Scott-Heron and the Last Poets, lyricists from the ’70s whose candid rhymes took white America to task. “They spoke of the trials and triumph in a town-hall, spoken-word kind of way,” Chris said. To his point, woods undoubtedly cuts this type of poet, as a lyricist who figuratively grabs your shoulders and shouts in your face. When I hear woods, I hear Killah Priest, the Wu-Tang-affiliated rapper whose elaborate rhythmic pattern and plainspoken cadence—through various guest verses and on his 1998 album, Heavy Mental—touched on everything from the tenets of the Five-Percent Nation to the shooting death of his cousin in an elevator.

This tenacity has served woods well to this point. An indie rapper before indie was popular, he’s taken a more traditional path to acclaim, releasing projects at a slow and steady clip, earning fans little by little with each drop. Now, vinyl runs of 2,500 nearly sell out on the first day, and it isn’t surprising to see him share space with noted rap acts like Sweatshirt and the Alchemist, who produced Armand Hammer’s 2021 album, Haram. In a world driven by celebrity worship on social media, woods keeps a low profile, never showing his face in pictures, not unlike the late rapper MF DOOM, who always performed in a big metal mask. “In the beginning, it was for a more practical reason; later on, it was an aesthetic choice,” woods said. “Then time passed, I’d been doing it, then I thought, ‘I like it this way.’” Though as he becomes more popular and does more shows, he runs the risk of being recognized, upending his plan.

At the end of lunch, woods mentions a few shows he’s got coming up, and the music he’s working on for this year. He’s not worried about momentum; he’s just trying to get better, still searching for the truth. That’s not to say he wouldn’t mind a bigger audience. “I’ve already mastered the art of laboring in obscurity,” woods told the Washington Post in 2021. “I did that for a good long time. Don’t need to do it more.” Based on his current trajectory, it seems he won’t have to toil much longer. He might be the most popular underground rapper in the world right now. His stature is a testament to staying the course, to keeping true to creative vision no matter what.

“Eventually the magic will fade or I’ll fall off,” woods said. “But until then, I fully intend to keep trying to push to the next level until I can’t.”

His is a global vision that centers the everyday aspects of Blackness, not the superhero narrative that sells television shows and books. In woods’s world, Black people can be regular folks with anxieties, delights, and disappointments. Maybe we drink chilled champagne from the bottle and watch a basketball game after work. Perhaps we appreciate visual art and obscure indie films. To woods, these things aren’t astronomical; they just are. He’s carved a formidable career through this perspective and doesn’t plan to slow down. “I recognize that sometimes the last person to know that you’re not that good anymore is you,” woods continued. “So I try to be cognizant of that and not stand still. Hopefully, I’m still at the point of doing things with some sense of vision and purpose.”