Was It Cooler Back Then?

A search for the memory of R.E.M. in Athens, Georgia

By Benjamin Hedin

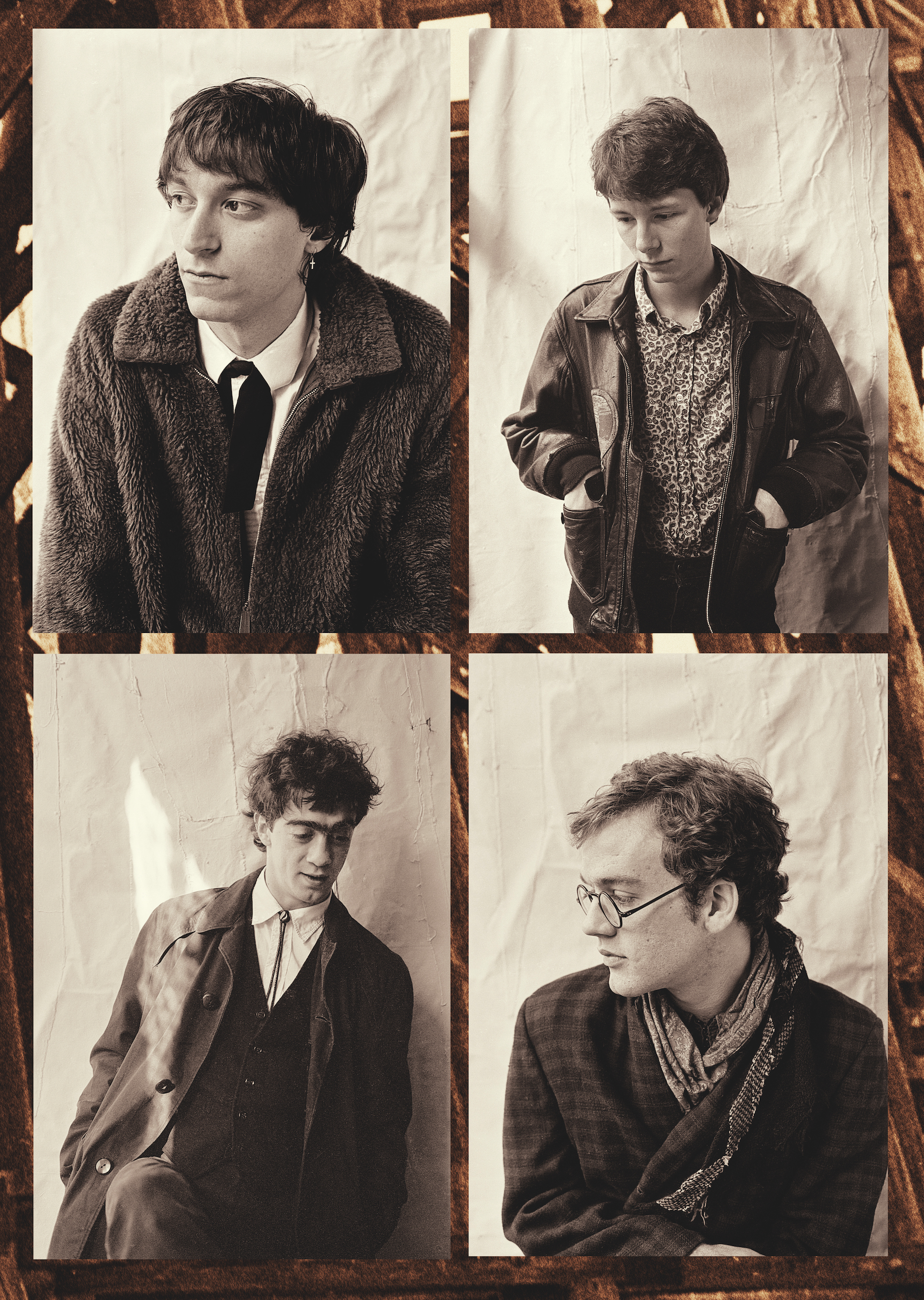

Outtakes from the cover shoot for R.E.M.’s Murmur, 1983 © Sandra-Lee Phipps

It is a truth universally acknowledged, A. E. Stallings and I agreed, that things were cooler before you got there. This seemingly incontrovertible fact came up as we were discussing her college days. Stallings, the author of four books of poetry, including the recently published selection This Afterlife, was raised in Atlanta and moved to Athens to study at the University of Georgia in the fall of 1986. Athens, back then, prided itself on its status as a bohemian outpost in the Deep South of the Reagan years, a place where indie rock, folk art, and camp fashion collided. “There wasn’t a feeling,” as Stallings put it, “that art was being made elsewhere. You didn’t feel like you had to move to New York. You were in Athens, Georgia.”

The consensus darlings of the scene—not that they would ever be labeled as such—since the hipster code of Athens demanded an aloofness from things like celebrity, were the members of R.E.M.: Bill Berry, Peter Buck, Mike Mills, and Michael Stipe. By 1986, R.E.M., who had formed in Athens and played their first gig in a church in April of 1980, had acquired a national following, and would soon leave their small independent label, I.R.S., to sign with Warner Bros. But there were several other accomplished acts in Athens at the time, like Love Tractor, Squalls, and Dreams So Real. As well as fledgling ones. Stallings can remember attending song swaps with Vic Chesnutt, and on Tuesdays she and her friends would wander over to the Uptown Lounge, one of the venues downtown, pay three quarters for a beer and listen to a group that had just been given a residency at the club: Widespread Panic.

Which sounds pretty good, only a slight exaggeration needed to call it paradise. And paradise, as we all know, is by definition lost, unrecoverable. When I asked Stallings if there was any trace left of the world she was telling me about, or whether it had totally vanished, I was surprised by her answer. She said, “I think it was already on the verge of vanishing when I was there.”

By this she meant the freewheeling ethic of creativity and play that defined Athens was starting to fade, overwhelmed by hipster self-consciousness on the one hand and mass popularity on the other. When members of sororities and fraternities started dressing up for an R.E.M. show, she said, you knew it was over. Yet we also recognized the structural or ritual quality of this lament. It doesn’t matter where or who you are, things were always cooler before. Stallings had friends who said no, you should have been here two years ago; they, in turn, had friends who said the same thing, and so on, back to some distant and prelapsarian point of origin. Whereas for me—I am about a decade younger and knew R.E.M. only when they were the lodestars of MTV and Rolling Stone—Stallings’s time in Athens sounds incomparably vivid. I chose to attend a school in Virginia in part because Athens, in 1996, didn’t resemble what I imagined it to have been in 1986, and even now I would still trade in my undergraduate experience for a seventy-five-cent Rolling Rock and an early look at Widespread Panic.

The storybook, in other words, didn’t match up, hers and mine. They had the same title—“Once Upon a Time, in Athens, Georgia”—and the same point-of-view, in that neither of us was around to witness it. Yet they differed in chronology and in tone, as mine was a largely celebratory projection and Stallings’s version contained the hint, the specter, of loss.

After our meeting, I decided to make a series of trips to Athens. I wanted to learn more about the world R.E.M. came out of, the one Stallings said had vanished, and along the way I figured I’d also see how the band is being remembered or commemorated there. I spoke with Mike Mills and Michael Stipe and told them what I was up to, even though I felt they had already given their blessing to such a project. For it’s one of the great fixations of R.E.M. and their work, the conjurings we make of the past—and the mythic value they tend inevitably to assume.

Revisiting that time, as I quickly discovered, it can be fun trying to sort out what is fact and what isn’t. Stallings told me, for example, that by 1986, R.E.M. was so popular that if they wanted to play at one of the clubs downtown they would have to do so incognito, under an assumed name. Scanning the week’s flyers, she would look for a band she hadn’t heard of. That was the tell, she said, the giveaway of which one might be R.E.M. in disguise. Often, however, “if you went out to see an unknown band called Beast Penis, it would end up being Beast Penis.”

It’s a good yarn, with lots of romance, and is neatly instructive of the town’s covenant with R.E.M., the futility of them trying to do anything in Athens without everyone immediately hearing of it. Maybe it’s too neat. As Stallings told it to me, I wondered if the story was a piece of local apocrypha, the kind that is fashioned ex post facto, and slowly, through multiple retellings, gets hardened into scripture.

But Mills told me it was true. “We didn’t do it very often,” the bassist for R.E.M. said when we spoke in August, “just a few times, if you didn’t want to play a real show, just get up there, goof off and have fun.” Once, he recalled, R.E.M. performed under a name gleaned from a newspaper headline: “Hornets Attack Victor Mature.”

I met Mills at the 40 Watt, the last of the smaller clubs from that era still in existence. It began as a rehearsal space for the band Pylon—a second-floor apartment lit by a single bulb—and though the 40 Watt has changed locations a number of times before settling into its current digs on Washington Street, it does a good job of holding on to these austere roots and remaining happily resistant to improvements or frippery. There are bars on both sides of the floor, in front of the stage, and that’s about it. The only notable piece of decoration is a sign hanging over the exit. TYRONE’S O.C., it reads, in tribute to another of Athens’s great clubs, Tyrone’s on Foundry Street, destroyed by fire in January of 1982.

R.E.M. Barber Street, Athens, GA, 1982 © Sandra-Lee Phipps

Mills, who had grown up in Macon, relocated to Athens in 1978. Rent in those days was cheap. Stallings can remember “a lot of old Victorian houses that had been chopped up into apartments, though they might be vermin-infested and the plumbing might not work very well,” and Mills, along with his friend Bill Berry, soon to become the rhythm section for R.E.M., were able to find rooms in a house for forty dollars each.

Stipe got there a year later—much to his dissatisfaction. He had been living with a punk band in St. Louis and moved to Athens, where his parents had retired, only because he ran out of money. “I always thought it was this hippie cow-town,” he said recently, “and I didn’t want to have anything to do with it.”

When talking about the person he was forty-plus years ago, Stipe can be endearingly honest, particularly when it comes to the immodesty of his teenage ambition. “My intention in 1979,” he told me matter-of-factly, “was to start a band and become world famous.” It didn’t seem like you could do that in Athens, though after entering the Arts School at the University of Georgia, Stipe was able to locate and attach himself to what was brewing in town. “The Athens scene was very small,” he said, “thirty people, maybe thirty-five people, when I arrived in ’79. It was so underground I didn’t know about it for the first six months I was here.”

There may have been no one else in that set who dared to covet world fame. As the calendar switched to a new decade and R.E.M. and other bands got together, there was a lot of punk, and post-punk, to be heard in Athens. But some of the music also demonstrated a streak of the avant-garde, a willingness to embrace the antic and outré. There were groups, like Pylon or Limbo District, that did not even consider themselves bands in the ordinary or conventional sense, but saw their music as one piece in a larger, more abstract field of expression. Michael Lachowski, the bassist for Pylon, who like Stipe was a student in the Arts School, said the group was not interested in writing songs but “assembling things with sound and instruments.” Play was the objective, in itself, not garnering mass appeal, which seemed too farfetched to consider in any case.

I asked Mills what downtown was like, circa 1980 or 1981. “Was it hopping?”

“No,” he said, “it was not hopping in any way.” Clubs like the Uptown had yet to open. There was a small array of shops, locally owned, but only a few establishments with a liquor license, and they all closed early on the weekends anyway. This meant the crucible of Athens became the house party, the Saturday night salons where bands could rehearse and artists and filmmakers could meet. In those years before social media, Mills said, there was even a number to call. A voice would answer, “Hello, you’ve reached the Athens party hotline,” and give the appropriate address for the evening.

I told Mills it was very hard to connect the place he was describing with the streets and neighborhoods I had spent the morning driving through. If you live in Georgia, you hear a lot nowadays that being in Athens can feel like being in Atlanta. And it’s true. It could be Atlanta. Or Durham or Nashville or any number of places. The downtown is constantly ringed by cranes and construction zones and road closings, a result of all the new apartment complexes going up, and the franchises, which used to prefer the mall on the Atlanta highway, have moved into the blocks surrounding campus. Most days, the busiest point of commerce is the Chick-fil-A at the corner of College and Broad, and many of the vintage clothing stores, once prized for their bargains, have shuttered, replaced by trendier shops with signs in the door that read “By Appointment Only.”

Mills, who lives up the street from the 40 Watt, said there is still a vital and close-knit music community to be found in Athens. And I know how much dwelling on the 1980s bothers longtime residents of the town, who rightly see in all the fascination or nostalgia an implicit criticism of Athens as it is now. For them, to glorify the house parties and cheap rent is to indulge in a sentimental fantasy, and some people will roll their eyes when you ask if they ever went to Tyrone’s. What is it you want to know, their glazed expression seems to ask, if things were cooler back then?

At the same time, it was becoming clear to me that things do disappear. We forget this can happen in the South, where the past tends to outstay its welcome, yet it’s a view that Mills was willing to sponsor. He told me the heyday, the most blissful part of being in Athens, was almost impossibly evanescent, lasting only about a year or two, and was effectively over by the time R.E.M.’s first record came out in 1983. What ended it? Knowledge, naturally: the forbidden fruit, the ancient enemy. People started moving there to take part in whatever it was that was happening, and the media took notice. “O Little Town of Rock ‘n’ Roll” ran a 1984 headline in the Washington Post, above an article comparing Athens to Beatles-era Liverpool and Grateful Dead–era San Francisco. There was a narrative now, a national focusing. Two years later, filming commenced on a documentary, Athens, Georgia: Inside/Out, that featured R.E.M., Pylon, Love Tractor, and others. It was as if a giant mirror had been set down in front of the town.

“They say about a certain kind of particle that the act of observing them makes them different,” Mills said. “Same thing with a scene. Once you start observing it and coming here to see it, then it’s very different. The scene’s probably over at that point.”

Here it was again, the sense of a vanishing, the same Stallings had noticed. Moreover, and somewhat uncomfortably, I was realizing how this band I have listened to and taken for granted my whole life was in fact a very delicate and contingent entity. “Back then we didn’t know what we were doing,” said Mills, who stressed how vital of an agent this lack of self-awareness was, how crucial to R.E.M.’s development. And what if it had been otherwise? A question, of course, nobody can answer, yet one that kept presenting itself to me as I drove around the streets of Athens, trying to reconstruct the town as it was. If Athens had already been “Athens” in 1980, would there still be an R.E.M.?

At one point, my conversation with Mills drifted into the subject of memory. He had been telling me about some of the clowning around that went on in the clubs, where it was common for one member of a band to join another’s set, and I brought up the last track on Green, R.E.M.’s sixth album and their debut for Warner Bros. It’s a song that was hidden from the album sleeve and so appears as “Untitled” in streaming platforms, and when it came time to record it Bill Berry and Peter Buck switched positions, with Berry playing guitar and Buck the drums.

“Swapping instruments is something we did just to change things,” Mills said. “We’re all capable of playing multiple instruments. So why not do it?”

“Untitled” is sung by Mills and Stipe together, in call-and-response, the lines about leaving home, as the song seems written to contain all those messages we can’t bring ourselves to deliver to our parents on such an occasion. “I made a list of things to say,” they confide, “When all I want to say / All I really want to say is / Hold her, and keep him strong / While I’m away from here.”

“It’s a very sweet song,” Mills said, “about family and remembrance, and I think there’s a Southern element in that song, in the sense of part of being from the South is that you remember. The history of your family is very important. I can find chunks of my relatives in five or six towns across Georgia. Way, way back. That sort of connection to the past is, for better or worse, a very important part of being from the South.

“And the fact that not only do we have that connection, but we talk about it, we have stories about it, families sit around and the grandparents tell the grandkids: This is where you come from, this is who you come from.”

People are sometimes surprised to discover R.E.M. is from Georgia. They are almost never identified as a Southern band, not in the way the Allman Brothers, for instance, are. Which is understandable. Musically, their influences point not to the South and its vernacular traditions but to New York, to the Velvet Underground, the Ramones, and Patti Smith. And then there is the range of their catalog, the power it has to exhaust all rubrics, the songs moving freely from one kind of style to the next, from more classical or anthemic forms (think “Stand” or “Shiny Happy People”) to the bizarre, ludic, and experimental (“Country Feedback,” “Oddfellows Local 151”). In the end, with R.E.M., all the descriptors fall away. Indie rock, college radio, these won’t do the job, either. Listening to them, you’re where you want to be: in a land of irreducibility.

For all that, though, as Mills indicated, their work betrays a recurrent concern with Southern places and Southern themes, especially in the attitude displayed toward the past, or memory, which is presented as the site of both catastrophe and wonder. In 1985, for their third album, R.E.M. released a song cycle of the American South, Fables of the Reconstruction. Its title sounds like some anthology of Southern fiction, a compendium of weird and tragic tales pieced together in the last century by a professor who had fallen under the spell of New Agrarianism. And the lyrics do limn a kind of Gothic dreamscape, a Southern underworld of desperation and thinly muted hysteria, peopled by eccentrics, runaways, and drifters.

“Fables was me pulling from real life,” said Stipe, “attaching these more mythic characteristics to real people.” “Life and How to Live It,” for instance, is based on Athens recluse Brivs Mekis, who built a wall in his house, dividing it into separate apartments so he could live alternately on one side, then the other. And R.E.M. took the name Wendell Gee from a car dealer outside Athens, appropriating it to write, in the album’s last song, of a man “reared to give respect” but who chooses that ultimate act of apostasy, suicide.

The songs all move swiftly toward some tragic outcome. They contain snapshots of an older, preindustrial South, a time when trains were the dominant form of travel and farms the cornerstone of the economy, though it’s no pastoral idyll that is being summoned but instead a land of attenuation, of greed and menace. In “Green Grow the Rushes” Stipe invokes the refrain of an old Scottish ballad, contrasting its promise of renewal with the South’s reliance on peonage. “Pay for your freedom,” he sings—the line is about migrant crews but could just as easily be about sharecroppers—“Or find another gate / Guilt by associate / The rushes wilted a long time ago.”

In these works, as in the later political ballads “Cuyahoga,” “Exhuming McCarthy,” and “Orange Crush,” historical memory is freighted, tinged with foreboding and premonition. “Sometimes I feel like I can’t even sing, I’m very scared for this world,” Stipe says in the first line of “You Are the Everything,” another song on Green.

Yet R.E.M.’s corpus is also full of countless scenes of the kind Mills was describing, personal, more intimate strophes that testify to the importance of kinship and the durability of remembrance. Alongside the larger, public myths of history, their work records the smaller ones, more crooked, localized, and uniquely our own, that we invent and inherit. We need to do this, their music asserts, ruffle through the back pages of our lives until we have found the centering. After that opening confession, for instance, “You Are the Everything” begins to relate ordinary scenes from youth: riding in a car with the windows down, a family reunion, the sound of “voices talking somewhere in the house,” and suddenly we’re in a clearer, changed realm. “I am in this kitchen, everything is beautiful,” Stipe sings, and the verse ends with a powerful backward genuflection: “You are here with me, you are here with me, you have been here, and you are everything.”

In writing the lyrics to Fables of the Reconstruction, Stipe said he hoped to trace an arc “from real life to fantastic,” and ultimately, I think, this could apply to many of R.E.M.’s songs, songs like “You Are the Everything” that depict so finely the way remembered incidents take on a fabulist aspect of their own. When I said this to Stipe, he didn’t disagree necessarily, but wanted to make sure I understood those lines of his were composed. As opposed to confessed. “I’m not an autobiographic writer,” he said. “I never was. I can count on one and a half hands the number of songs over thirty years that are truly autobiographic.”

It is, naturally, an unintentional byproduct of writing in the first person that people will hear it as a memoirist outpouring and assume that in “You Are the Everything” Stipe is singing about his kitchen, or his family. Recalling what Mills had said about stories that get told across the generations, I mentioned “Try Not to Breathe,” off 1992’s Automatic for the People. One of Stipe’s most affecting lyrics, it captures the moment when an ailing elder submits to death, though not before offering these closing words: “I want you to remember.” The song, Stipe told me, was inspired by his grandmother, who “was approaching the end of her life when that record was being made. But there’s nothing about it that’s directly about her. I just used the experience of being around someone at that point in their life to try to imagine what it feels like to be inside that body, while you’re trying to navigate the inevitable.”

Often, Stipe said, these second selves and invented voices emerge when he is stuck, when the draft won’t move and he is looking for a way to circumvent the stock formulas and clichés of songwriting. “I’m writing in the medium of pop lyrics,” he said. “There’s decades of love songs, let’s say—that’s the easiest one to shoot out of the sky—that follow a certain kind of imprint. Adding a personal touch to a song that feels very general, or very plain, throws it into a whole different area.”

Stipe’s process of songwriting, then and now—he is about to release his first solo album—seems to be one of slowness and deliberation, even agony. It is not uncommon for him to spend two or three years completing a lyric, and the effect I noted earlier, of how R.E.M.’s songs testify to our need to retrieve and enshrine what would otherwise be lost, was not incidental, and not easily arrived at. It was a carefully wrought construction.

Entering Athens from the southeast, as people do if they’re driving on Highway 78, a curious sight awaits: as you cross the North Oconee River and start up the hill to downtown, on your left, tucked amid a shopping plaza and grid of condos, is a steeple, taken down from its former height and set on a small pedestal of rocks. Why it’s there is not apparent, since there’s no sign, no nameplate, and to those who have just moved to Athens or come to tour one of the condos, it must appear strange, this church tower taking up a parking space, with its peeling sections of paint and door that ironically invites you to enter. It could easily be mistaken for a piece of sculpture or some urban installation. In fact, this is what remains of St. Mary’s Episcopal Church, where R.E.M. first played in front of the public on April 5, 1980.

I’ve always loved this, the way the band seems to greet you as soon as you get to town, and in the sort of offbeat or humble fashion R.E.M. would probably desire should there ever be an official monument to their work. But there’s not. In Athens you will find no Paisley Park or Graceland, no votary temple where you can fork over fifty dollars to view a sheaf of handwritten lyric drafts or one of Stipe’s cameras, then buy a plush doll of Peter Buck on your way out. Certainly, there could be—not far from downtown is a warehouse where R.E.M. stores their old tour sets and other artifacts and memorabilia—and it is easy enough to envision a museum being built in the future, though as Stallings reminded me, any sort of monolithic capitalist shrine “would not be cool” and therefore would represent a transgressing of the spirit of Athens as much as an honoring of it.

In the meantime, R.E.M. on their native ground seems poised at an odd midpoint, both omnipresent and slipping from view, glossed over the way Civil War cannons are, and eroded statues and historical markers. More than two generations have passed, after all, since they ruled the town. One afternoon I was in line at Weaver D’s, the venerable soul food eatery on Broad Street, a few blocks north of the steeple. Someone behind me, noticing the concert posters and photographs of R.E.M. that adorn the walls, asked, “Did R.E.M. eat here a lot, or what?” The other people in line shrugged. For a moment I felt the urge to interject, but what was I going to say? Things were cooler back then? Another customer mentioned that Kate Pierson of the B-52’s sang backup on “Shiny Happy People.” And there the conversation ended. The whole time, meanwhile, the answer to the question could be glimpsed through the window, on the marquee of the restaurant where, below the name Weaver D’s, reads its motto: AUTOMATIC FOR THE PEOPLE.

Certainly, R.E.M. could do more to keep their name current—or at least they could try, the way so many others do, and make a few million along the way. But they are comfortable in the past tense. More than comfortable; it’s where they want to be. “We kind of grew up in public,” Stipe said, “and I’m just as proud of the disasters and the times that we fell on our face as I am of the triumphs.” The group disbanded in 2011, after the release of their final record, Collapse Into Now, and there has not been the breath of a credible rumor since about a possible reunion. There is dignity in this, a restraint seldom offered in today’s era of the farewell tour, of ticket-and-cruise packages with prices that top four and five figures. R.E.M. wanted their career to have a formal roundedness, a logical shape, so when they stopped making music, they stopped being a band. There was no longer any reason for the story to continue. They are content, then, to retreat, to become less a living presence than “almost mythological,” in Stallings’s words, at least around Athens. Having chronicled the progression in so many of their songs, they, too, are now passing from real life to the fantastic.