Slow Train

How “The Letter” put Al Green and Alex Chilton on track to fame

By Elle Perry

Al Green, ca.1973 © United Archives GmbH/Alamy

In Take Me to the River, his 2000 autobiography, Al Green wrote about his God-given gift of singing. Green remembered a teacher in his eastern Arkansas elementary school asking each child in the class what they wanted to be when they grew up. His answer was “singer,” causing the other children to erupt in laughter and the teacher to admonish him for being unrealistic.

Green, then Albert Leornes Greene, joined his family’s gospel group, the Greene Brothers, when he was around ten. The group continued performances after the family fled the Mid-South’s poverty for the promise of Grand Rapids, Michigan, where they found similarly hard circumstances, just in a colder climate. When he was sixteen, Al Greene started a high school band named Al Greene and the Creations. In the late 1960s, they became Al Greene and the Soul Mates. Dissatisfied with their original record label, the group self-released a single called “Back Up Train.”

In the song, Green asks the conductor to turn the train around so that he can retrieve his lover and cure his loneliness. The bass feels like a train slowly chugging along the tracks, even halting at times. The Al Green here is restrained, but glimpses of the future sex symbol are evident—it’s very clear how, with stripping away the Motown-esque background singers and adding brassier production, Green’s career could take off to soaring heights.

The song became a hit, leading to a tour and an invitation to New York’s famed Apollo Theater, where Al Greene and the Soul Mates performed nine encores of “Back Up Train.” The group’s next two singles made little noise, however. Same went for the Back Up Train album. “With the failure of [singles] ‘Don’t Hurt Me No More’ and ‘Lover’s Hideaway,’ along with the instant oblivion of our album,” Green wrote, “it was all too clear that we’d have to come up with a new set of dreams to keep us going.”

The group disbanded, and in the summer of 1968 Al Greene became Al Green. He then embarked on a solo tour, never escaping the demands for “Back Up Train”—a song that he more than once said that he wasn’t particularly fond of. He groused that the “dumb song” seemed to be turning into a curse. Not only would he have to perform it at every show, but often multiple times per show. Looking back, Green described those months of Midwestern and Southern chitlin circuit gigs as some of the lowest moments in both his career and his life. “Back Up Train” was the key to the success that he’d had up to that point, and he found himself unable to escape it, even as he yearned for a new, solo identity and career.

That tour, though, would lead to a divine intervention. It would bring him into the direct path of Memphis musician and producer Willie Mitchell, of Hi Records and Royal Studios fame. In 1969, under Mitchell’s tutelage, Green would record his debut solo album, his first release under his new stage name. The album was considered a breakthrough, and it began a fruitful musical partnership. Two years later, 1971 would bring “I Can’t Get Next to You” and “Tired of Being Alone.” A year after that—“Let’s Stay Together.”

But before those hits would cement his status as a soul legend and Memphis icon came that first solo album, Green Is Blues. Green wrote that Mitchell’s technique of introducing a new player to the scene was to have them cover well-known songs and add their own twists. Track four of Green Is Blues is a cover of a hit record by another Memphis outfit, released two years prior: the Box Tops’ “The Letter,” which features a then-sixteen-year-old Alex Chilton singing lead.

On Green’s version, horns are added, as well as soulful backing vocals. Chilton’s gruff yearning for his baby is replaced by Green’s plaintive pleading for his own. Like in “Back Up Train,” the protagonist is dying to see his lover and mass transit is involved. Only in “The Letter,” a train, even a fast one, won’t reunite him with his beloved soon enough. Although in both instances percussion brings the listener into the song, in Green’s version, the song is slowed down considerably. The lamentation is a groove. Over the course of nearly two minutes and thirty seconds, Green’s lonely agony increases rapidly. By the end, he’s doubled the “listen mister” of the original into “listen to me mister, listen to me mister.” Instead of singing the word “yeah,” Green instead treats listeners to his signature, toe-curling screams. Although not a song devised by his record label, this tune is emblematic of the Green tracks that throngs of fans would come to love.

Green described Green Is Blues as a “warm-up” album, disappointed that it lacked a hit single and unenthusiastic about its covers of popular songs. In the case of “The Letter,” however, the cover made sense to Green because it started off as a soul song—rather than being converted to one. The selection also reflected Mitchell’s premonition that white and Black and pop and soul music would co-mingle, according to Green. This cover was a natural fit, Green believed, in contrast to the attempt to recreate and reskin the Beatles elsewhere on the album.

Green Is Blues and “The Letter” would push Green toward his chart-toppers and greater artistic autonomy. Two years earlier, the song had a similarly transformative effect on its original singer, Alex Chilton. “The Letter” achieved several things for him: It pushed the Box Tops and Chilton into the stratosphere of teenage-pop stardom; it would also alienate Chilton from the mechanisms of that scene.

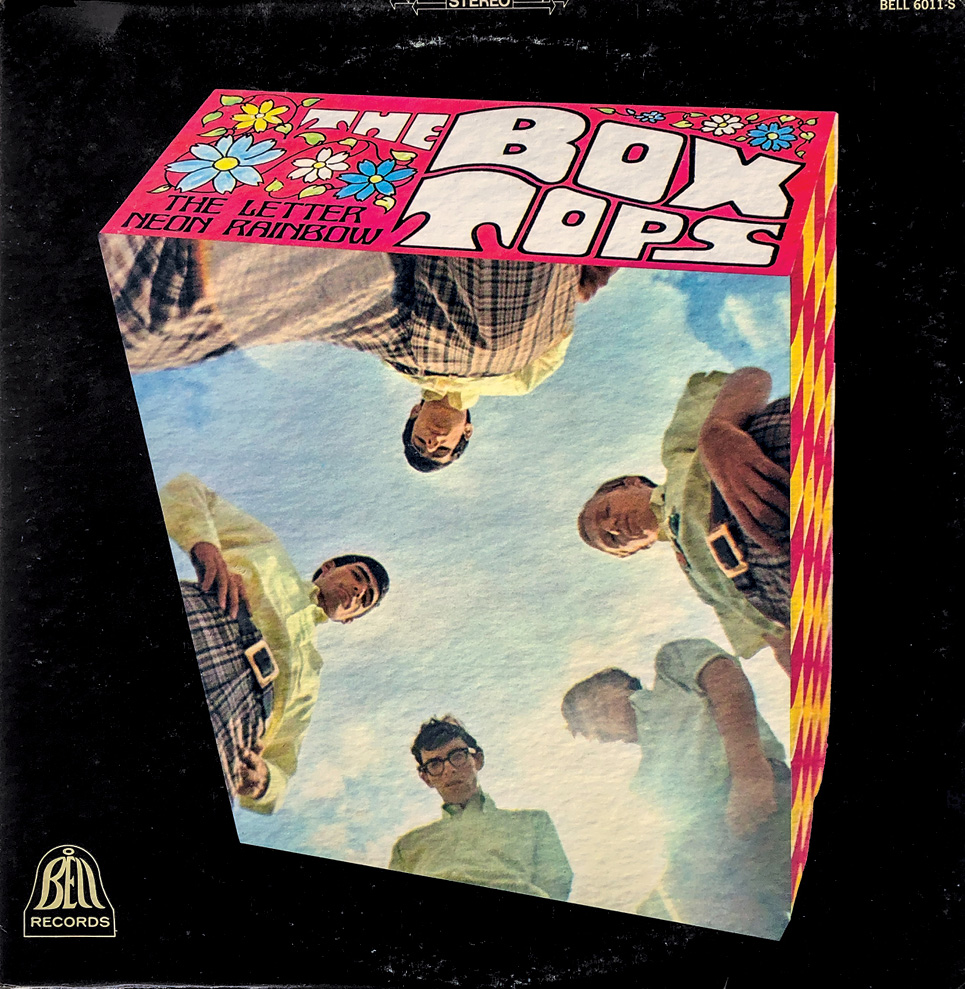

“The Letter/Neon Rainbow” by the Box Tops. Photograph by Carter/Reddy

Chilton had joined the Devilles, a Memphis garage band, after he performed at a Central High School talent show. “The Letter,” written by Wayne Carson based on lyrics sent by his father, was one of three songs American Studios operator Chips Moman asked the band to choose from for their first recording session. Dan Penn was the session producer and the one responsible for requesting Chilton to sing ae-ro-plane, three syllables, instead of air-plane, two syllables. (That memorable pronunciation is carried into Al Green’s rendition.) Chilton later described his voice at the time of recording as being hoarse, blaming a hangover and sleep deprivation, as well as a common cold. His raspy tone suited the song perfectly.

When the song was released, the Devilles—as the name was already taken—were renamed the Box Tops. “The Letter” reached No. 1 on the Billboard Hot 100. In less than a year’s time, Chilton had gone from talent show participant to a bona fide pop star. “The Letter” would be followed by more hit songs, a hit sophomore record, and a slew of concert performances and TV appearances. Privately, Chilton chafed at the bland musicality of the songs he performed. A friend recounted Chilton being bored and hating going through the band’s hits at concerts. Perhaps unsurprisingly, the band’s life was short. For Chilton and the band, performing became a chore—just a paycheck—and their disinterest was apparent to audiences. Discontent grew within the band, with some members unsatisfied by pay disparities between Chilton and themselves. At the same time, the band’s songs made less and less noise on the charts. By spring 1969, Chilton was secretly planning his solo album; a year later the band dissolved.

While Green expressed displeasure with covering other people’s songs, Chilton expressed similar disdain about singing other people’s lyrics. In Robert Gordon’s It Came From Memphis, Chilton said the Box Tops’ songs were only “marginally” his, going on to say that while listening, he heard Penn rather than himself. A girlfriend of Chilton’s, Vera Ellis, said that the commercialism of the group had embarrassed him and made him feel like other musicians looked down on him. In 1971, Chilton would start the band Big Star, with Chris Bell, Jody Stephens, and Andy Hummel. The band’s debut album came out in 1972.

Big Star’s lauded (but commercially unimpressive) follow-up album, Radio City, was released fifty years ago, in 1974, when Alex Chilton was twenty-three. Green Is Blues was released in 1969, two days after Al Green turned twenty-three. Both entered the music industry as teens. Both started in doomed groups and went on to have solo careers. Both responded to their industry experiences by changing genres: Chilton from blue-eyed soul to power pop, and Green from sultry soul to gospel. Both became synonymous with a regional recording power—Chilton’s in Midtown Memphis and Green’s in South Memphis. And each man himself became a symbol of a genre, of a generation, of a city. Of that city’s talent. Although each man recorded “The Letter” at a different point in his life, for each it represented a turning point, both in music and their successes and challenges to come.