That Don’t Get Him Back Again

The legacy of Big Star’s “other genius”

By John Jeremiah Sullivan

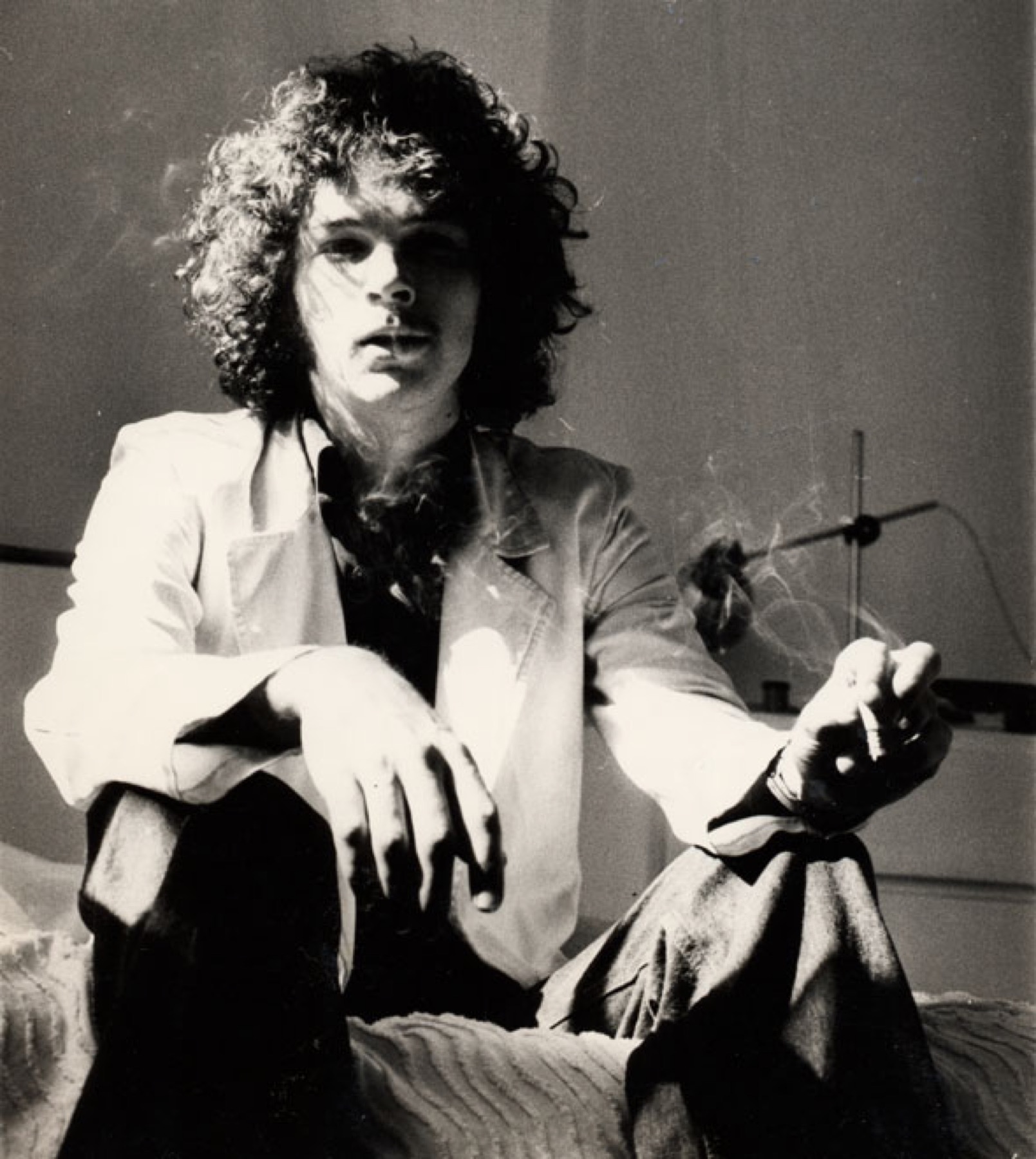

Photo by David Bell.

About the only thing you do not find much of in It Came from Memphis, Robert Gordon’s history of the profoundly twisted cultural scene that obtained in that city from roughly 1950-1975, is tragedy. (I mean within the scene itself, of course; outside of it, the entire period was pretty tragic.) There is plenty of awfulness: people rushing headlong into bad ends, talent going unrecognized, that sort of thing. But overall, the sense you get from Gordon of the time and the place is one of antic, if at times frustrated, exuberance. The freaks were out, day and night, and they found one another. It was "gross weird," as Terry Southern would have said.

The story of Christopher Bell, which Gordon includes, is tragic. It is also, in other ways, quintessential: He was a white boy, a "rich kid" from an affluent Memphis neighborhood, whose well-greased path through conventional society was ambushed by rock & roll. In high school, he formed the requisite cover bands (the atrociously named Christmas Future was one), playing not roots music per se, but the "new" stuff: Hendrix, the Yardbirds, British Invasion. Eventually he angled his way into Ardent Studios, where he became an apprentice engineer, taking actual morning lessons (8:00 a.m. sharp, drunk or sober) from the studio's founder, John Fry. At Ardent he met, or was reintroduced to, Alex Chilton. They had known each other in high school, but in the interim Chilton had become marginally famous as the lead singer of the Box Tops ("Give me a ticket for an aer-o-plane...."), gotten fed up with fame, knocked around as a desultory folkie in Greenwich Village, and finally come back home for a while, not really knowing what to do with himself. He and Bell tried out their tunes on each other, and Chilton was impressed enough that he tried to drag Bell back to Manhattan with him. The idea was to play as a duo, but Bell didn't want to leave Memphis. So Chilton stayed.

The result, with Andy Hummel on bass and Jody Stephens on drums, was Big Star. And the less said about Big Star here the better, since Chris Bell's near-anonymity has much to do with his status as the "other genius" in that much written about, much emulated band. Suffice it to say that Big Star invented power pop, loosely defined as unapologetically pretty and sophisticated melodies, with prominent harmony, played loudly and at times with an edge that approaches punk. (Didn't the Beatles do this? you ask. Yes. But pop fans live by razor-thin and barely defensible categories, and this is one.) Big Star made three records, each of which has multiple all-but-perfect pop songs on it. The third album, which is most often called simply Third, is a masterpiece. It's a huge dark haunted house of a record, every song a room, and stylistically no one song seems to have anything to do with any other. But Chris Bell had nothing to do with Third. It is an Alex Chilton project in all but name.

Bell’s presence fades from Big Star neatly, album by album. On the first, #1 Record, he was the dominant songwriter, sang half the lead vocals, and co-engineered. On the second, Radio City, he contributed only to the songwriting. That's saying quite a lot, in this case, since we have it on Andy Hummel's authority that he was the principal writer on "Back of a Car," a song that Rob Gieringer, in Judith Beeman's excellent, short-lived Big Star fanzine (also named Back of a Car), calls without exaggeration "one of the best pop songs ever written." By the time the final album came to be recorded, he was no longer a member of the band, and seems even to have become estranged from the band’s circle.

What happened was, in its particulars, a rock & roll cliché. Bell simply couldn’t understand why Big Star wasn’t famous. They had made a first-rate record, he believed (correctly, as the last thirty years have shown). What could possibly be the problem? The critics liked it, sure, but Bell wanted the girls and the jet. Chilton had seen all that already and knew what it was worth—or knew, at least, that it shouldn't be counted on. But the disappointment and audience indifference were more than Bell's fragile psyche could bear. Making things worse was the tendency of the media to focus on Chilton when they chose to pay attention to Big Star at all. This was natural, even good for the band, given that people knew who Chilton was. But mercenary logic like that tends not to work on tormented artists.

It’s possible that Bell was headed for a breakdown regardless. He was certainly prone to mental illness. Robert Gordon reports that even before Radio Citycame out, Bell "was actually seeing things." And heroin found him, as it routinely finds those who have least business messing with it. Something else that is rarely mentioned in writing about Bell but appears to have been widely recognized by those who knew him is his homosexuality. In Memphis, five years ago, there was even a rumor moving through the record stores that Bell was in love with Chilton, and that Chilton’s lack of reciprocation may have hastened the breakup of Big Star. It’s probably borderline libel even to mention this stuff, and for all I know Gordon may have purposefully left it out of It Came from Memphis because he doubted its veracity. Most of the published interviews with the other people involved in Big Star sooner or later come to a statement along the lines of, "Chris was having personal problems, and I won’t say any more about that." If he was gay, well, Memphis in the ’70s may have been full of freaks, but it was still in Tennessee. Randall Lyon, a highly influential Memphis scenester and open homosexual who also knew Bell, remarked to Gordon, "I was always out front about my shit, and their problem was they didn’t know what to do with a hip queer. It says a lot about the whole period."

Whatever the specifics of Bell’s sexuality, it was tortured; everything about him was tortured. His voice, on the recordings, is too sensitive. That’s meant not as an aesthetic judgment. It wasn’t too sensitive for the material, in other words. It was too sensitive for life. You listen to him sing, closely, and if you don’t know another thing about what happened to him, you know that the guy with that voice is not going to last.

This is true not so much of Bell’s work with Big Star but of his later solo material, collected long after the fact on a Rykodisc release titled I Am the Cosmos. It’s not really an album, just a bunch of tracks recorded from 1974–78 in Memphis and a boutique studio in provincial France. Bell’s brother, David, took him to Europe to help him quit smack and generally get himself together, and David Bell's liner notes to I Am the Cosmos are a loving, wrenching tribute to a brother whose demons his family could neither fathom nor help fight.

We can’t know how much of I Am the Cosmos Bell wanted released, and the quality of the fifteen tracks is wildly inconsistent. (For that matter, the first two Big Star albums are less consistent than most of their evangelists are willing to confess—rescuers from obscurity understandably feel that their job demands extreme enthusiasm.) Certain of Bell’s songs feel generic, others are knock-offs of songs that Big Star did better, one attempt at barrelhouse—"Fight at the Table"—is sort of embarrassing. But the four (by my count) stand-out songs are so ridiculously good that you just shake your head: at the idea that, with the exception of a rare and now quite valuable 45, these songs went unheard for fourteen years; and at the idea that the person who made this music never got to create a bona fide album of his own, never got to make his own Third.

I Am the Cosmos begins breezily, with one of the greatest, saddest goodbyes to the dreams of the late-’60s, early-’70s counter-culture ever put onto tape. Joni Mitchell had already sung that we had to get ourselves back to the garden. But Chris Bell knew that the garden had been mowed. If it was still there, it was no use: He had the spider inside of him.

Every night I tell myself

I am the cosmos, I am the wind

But that don’t get you back again

It would be funny, that verse, if it weren’t so freaking sad. It’s still a bit funny, which is just another sign of the maturity he was growing into, taking himself less seriously. The contemporary power-pop band the Posies, two of whose members round out the current Big Star reunion line-up, do a superb cover of "I Am the Cosmos," their note-for-note fidelity a tribute to how well constructed a pop song it is. In the middle is one of the coolest yeah, yeah, yeahs in pop, a descending, ethereal three-note thing that waterfalls down while the guitar rips back and forth between an A and an Em7.

The second track, "Better Save Yourself," opens jarringly with organ and a huge, minor-key guitar-god riff.

I know you’re right

He treats you nice

It’s suicide

I know, I tried it twice

We have it from David Bell that his brother had, in fact, tried suicide. In the throes of whatever drove him to it, he found Jesus and became a devout Christian, further complicating the psychological picture of his post-Big Star years. In "Better Save Yourself," he goes on to sing "You shoulda gave your love to Jesus/Couldn’t do you no harm." The past tense there is creepy. The righteous blues were about exhorting the listener (maybe the singer too) to get right with God, but it's too late for whomever Bell's talking to. "Shoulda Saved Yourself" would have been a more accurate title.

"You and Your Sister" is maybe the sweetest of Chris Bell's songs, three minutes and eleven seconds of flawless pop craftsmanship, the goofy cleverness of the verses ("Your sister says that I’m no good/I’d reassure her if I could") expertly balanced with the real beauty of Bell’s falsetto on the chorus:

All I want to do

Is to spend some time with you

So I can hold you, hold you

Chilton said to Robert Gordon, "Most of the Big Star stuff was searching for how to get through two verses without saying anything really stupid...." Add "playing" to "saying," and you have as apt a description of the task involved in writing good pop songs as has ever been articulated. Great songwriters learn as much from listening to bad music as they do from listening to what they love. They memorize pitfalls, dead-ends; the how, as opposed to the what, of poor taste and cliché. It's a strange, hair-splitting science, since, let’s face it, when you’re thinking in Shostakovich terms, the distance between a Brian Wilson objet d’art and a breakfast-cereal jingle is about three atoms wide. For a pop songwriter, each new composition presents countless temptations and traps, moments when the song wants to become "stupid," wants to go to the obvious chord or rhyme, wants to sound too close, as opposed to just close enough, to what we've heard before. The game is to thread your way through these traps without sounding as if you're trying to be unpredictable—melodically, lyrically, in whatever way. And success comes when you've taken all the crap the genre gives you to work with—limited instrumentation, limited melodic possibilities, limited time—and made beauty of it, then disguised the beauty as more of the good ol’ crap we like to hear when we turn on the radio. Isn't that precisely what makes those classics, like "Baby, It's You," so moving, so overwhelming, what makes you have to pull your car to the side of the road when they come on? The beauty in them is subversive. It doesn’t belong. It's been smuggled in under the radar of suburban teenage taste and purchasing power. That’s why pop music is the art for our time: It’s an art of crap. And not in a self-conscious sense, not like a sculpture made of garbage and shown at the Whitney, which is only a way of saying that "low" materials can be made to serve the demands of "high" art. No, pop music really is crap. It’s about transcending through crap. It’s about standing there with your stupid guitar, and your stupid words, and your stupid band, and not being stupid.

An example of what this sounds like, when pulled off, is Bell’s "Though I Know She Lies." It's primarily an acoustic song, not quite like anything else he did during or after Big Star. There's nothing revolutionary about it, except that it's gorgeous, and full of space, and that it's the hardest kind of song to write, insofar as in the wrong hands it would be treacle. The guitars on "Though I Know She Lies" are badly recorded—the electric cracks up at the high end—which has probably kept it off a lot of compilations. But the vocal performance is chilling as chilling can be while remaining tender.

When I look through your eyes

I tend to get bitter

Maybe I'm best advised

To look to myself

It doesn’t really even sound like Chris Bell; he’d never sung that well before, which makes it even harder to take, since it was the last, or one of the last things he did. So confident, and at the same time, somehow, so vulnerable. The song needs to be heard on headphones, because it's clear that he means to be singing straight into your head. Most striking of all is that at the end of the song, he doesn't sound like the same person. The song itself, the experience of singing it, seems to have done something to him, worn him out. Three and a half minutes have gone by, but he sounds ten years older. The chorus is simple:

I fall every time

though I know she lies

I can't stay away

But it's how he holds the words in his mouth, sings "staaay aaawaaay" from the back of his throat, like he’s physically trying to hold himself down in the bed, knowing he shouldn't go over there, shouldn’t call. There is only one line of harmony in the song. It comes out of nowhere, on the bridge, a quiet falsetto, maybe Bell's own. You can miss it so easily—you have to squeeze the headphones to the sides of your head. The line is "Keeping me in the dark."

That’s all I know about Christopher Bell. The Chairs, a power-pop band from Sweden, wrote a song about him in the mid-Nineties. It’s pretty bad. I have to lean again on Robert Gordon for the end of the story, which is that a couple of days after Christmas, in 1978, Bell crashed his car into a telephone pole on Poplar Avenue in Memphis, and was killed. As with most fatal single-car accidents involving chronically depressed people, suicide has always been suspected.

He was coming home from rehearsal, so music was still a part of his life. And thanks to the people at Rykodisc, who heard what dozens of A&R men had failed to hear, his music is still a part of ours.