Sandy Posey

Under his thumb and lovin’ it

By Steve Klinge

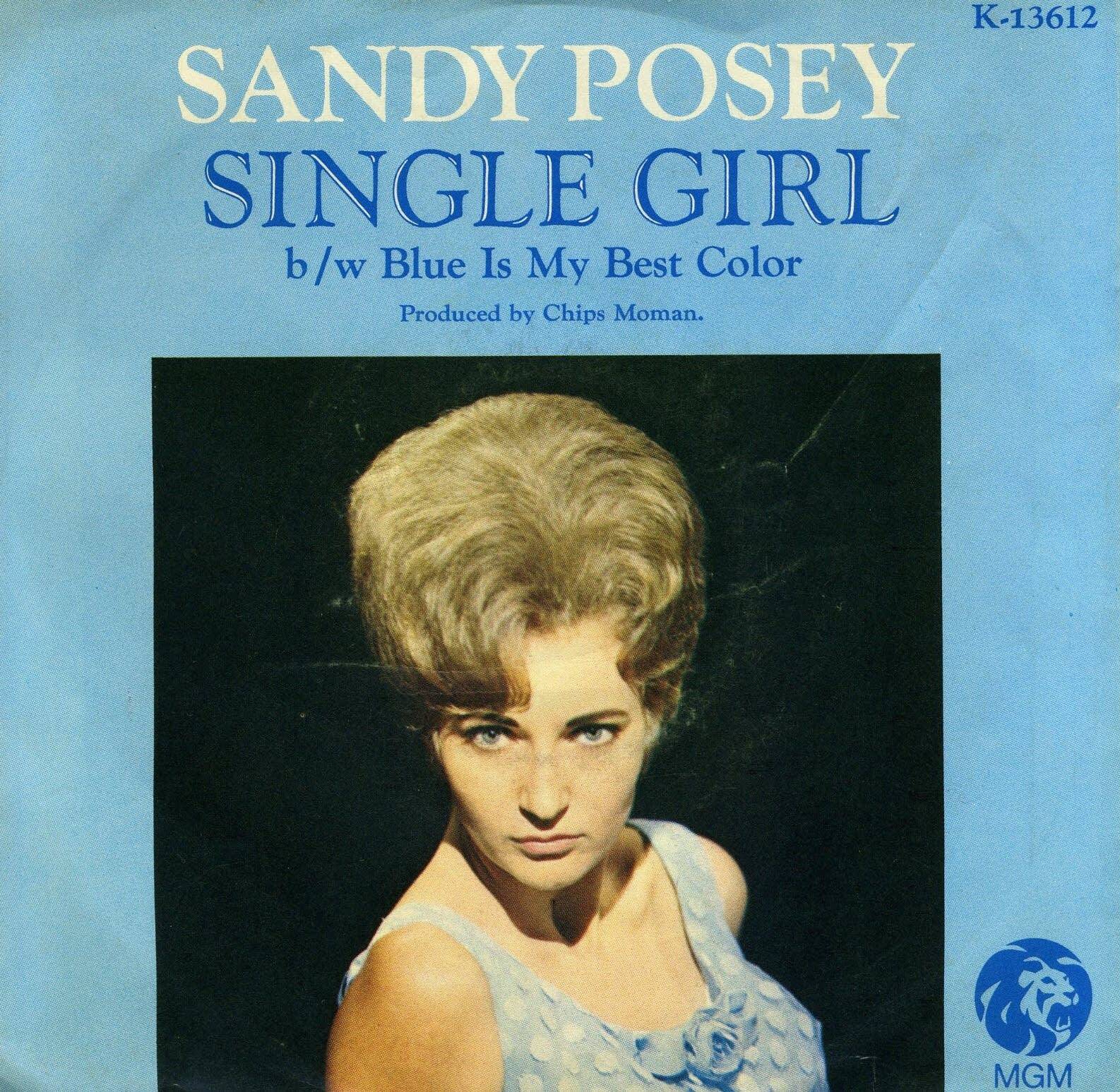

Single art for Single Girl by Sandy Posey, YearTK. © MGM Records

Makes no difference if you’re rich or poor

Or if you’re smart or dumb,

A woman’s place, in this old world,

Is under some man’s thumb.

And if you’re born a woman,

You’re born to be hurt

You’re born to be stepped on,

Lied to, cheated on and treated like dirt.

That’s the first part of “Born a Woman,” Sandy Posey’s hit single from 1966.

Posey sings it in a melancholy, sweetly drawling voice, bolstered with reverb and occasional double-tracking, atop a few soulful guitar chords and a pleasant trebly piano figure. She comes down harder on the phrase “a woman’s place,” adding a desperate edge, but then quickly eases back, resigned. The pace accelerates, gradually, and when she arrives at the list of male transgressions, she delivers them in sharp iambics with the piano and drums thumping out each stressed syllable. Then strings come in, softening the final lines. The style is on the cusp between girl-group pop and countrypolitan polish, with undercurrents of Memphis soul.

It’s a thrilling little drama that quickly hooks the listener. You can hear bitterness and frustrated anger and sage precautionary advice in Posey’s youthful yet not girlish voice. A woman’s place may be under some man’s thumb (you can’t help but think of the Stones’ “Under My Thumb,” which came out the same year), but she doesn’t have to be happy about it.

Unfortunately, she is.

Well, I was born a woman,

I didn’t have no say,

And when my man finally comes home

He makes me glad it happened that way,

Because to be his woman

No price is too great to pay,

Yes, I was born a woman

I’m glad it happened that way.

Huh? The strings that buoy the final verse add grandeur, a seemingly triumphant resolution that emphasizes the phrase “comes home he makes me glad.” At the final lines, they become soft and amorous. The song lasts only 1:45, and a quick fade-out begins in the middle of the last line; maybe there’s more to the story, but we’re not hearing it.

Posey was twenty-one when “Born a Woman” reached No. 12 on Billboard, launching her solo career. It also provided the blueprint for Posey’s persona, and therein lies the problem. Based on her brief flirtation with the pop charts, Sandy Posey is one of the least-emancipated female voices of the mid-’60s.

Posey’s early recordings are full of niggling paradoxes. They can sound like songs of innocence, but they present a voice of experience whose advice is, today, troublesome and weirdly unsettling. The Posey canon catalogs women who need men even though the men invariably mistreat them. Listening with post-feminist ears four decades later to these aggressively pre-feminist (anti-feminist? non-feminist?) vignettes, this male listener, at least, faces plenty of cognitive dissonance.

Songs such as “Born a Woman,” “What a Woman in Love Won’t Do,” and “One Man Woman” go beyond pledges of stand-by-your-man fidelity to become affirmations of acquiescence. She didn’t write those songs, but she is totally persuasive singing them. She is also one of the most criminally undervalued singers of the era, someone who, when at her best, was on a par with Dusty Springfield or Skeeter Davis or Mary Weiss of the Shangri-Las. Yet the music histories of the decade barely mention her, even though she sang on Elvis Presley records and was produced by the legendary Chips Moman at his American Studios in Memphis, with many of the same players and songwriters that Bobby Womack, The Box Tops, and Dusty Springfield (for Dusty in Memphis) used for some of their best records.

Somehow, it’s easier to process an irresponsible cheatin’ and drinkin’ song or a misogynist murder ballad or gangsta rap track than it is Sandy Posey’s anti-feminist pledges of fidelity. Her songs are not naive and sugary teenage pledges of love; instead, they make it clear that the woman, who is not a “girl,” knows she is sacrificing herself to a man who does not deserve it. They are songs of disempowerment, of masochism, of love gone bad voiced by a woman who will stick with it, not with steely resolve but with happiness because the love of her man solves all ills, even though she knows she is his victim. You want to yell at her, Wake up! Get the hell out of there!

I can hear Posey’s songs as a window into another time, or into a culture that’s still present (the feminists, after all, were the radical minority in the ’60s, and today “feminism” can be a dirty word, prone to backlash), or into a David Lynch–like world whose quotidian surface masks weird and disturbing psychologies. In any case, something about the women in these songs demands attention.

Or maybe the songs are just products of commerce in action, formulaic hits ready to be decoded, good bubblegum, silly commercial songs for silly boys and silly girls. Posey wouldn’t deny that now. The bouncy “Sunglasses,” for instance, is classic teenybopper candy; it’s a hoot.

Melodrama is very much a part of their charm, too. Posey excelled at spoken-word recitations, and ”I Take It Back” begins with one that could be a conscious “Leader of the Pack”/”My Boyfriend’s Back” allusion: “Here he comes now, I’ve got to tell him somehow,” she says, as a guitar twangs in the background. She wants to break off the relationship, but when she finally tells him “my love for you is dying,” everything—singer and music—balks. “Oh no, please don’t start crying,” she says, and the tempo shifts abruptly, mirroring the narrator’s dialectical dilemma. The song becomes a slow, string-kissed countrypolitan ballad à la Patsy Cline, and she retracts her statement. And then the bassline picks up, and the song begins again with another recitation.

He’s such a man,

It must have hurt him a lot if

he let me see him cry.

But I must try again.

This time, I’ll say goodbye.

Of course, he cries, again. And she takes him back, again. And the song concludes with a provocative aphorism: “Sometimes it’s better to be loved than it is to love.”

Absolute melodrama, but I love it. Posey sings with an ache in her voice; she is totally convincing on both sides—the leave-him and the love-him sides—and the clincher, that aphorism, is a fitting payoff.

Born in Jasper, Alabama, in 1944, Sandy Posey spent her teenage years living just outside of Memphis, across the Mississippi in Arkansas. With little formal experience but a lifetime of singing along to the radio to what she calls “all that doo-wop-shoo-bop stuff,” Posey started working as a background singer when she was only a few months out of high school. She quickly ended up on Percy Sledge’s “When a Man Loves a Woman” (which came out within months of ”Born a Woman”) and on songs by Bobby Goldsboro, Tommy Roe, and others. When she wasn’t doing session work, she worked as a receptionist—first at Sonic, then at American Studios.

Martha Sharp, a Nashville songwriter, wrote “Born a Woman.” Gary Walker, the song’s publisher, brought it to Chips Moman, who had had a recent hit with The Gentrys’ ”Keep on Dancing,” and Moman suggested Posey cut the demo. Walker, who would later become Posey’s manager, took her to Rick Hall’s studio in Muscle Shoals, the Alabama studio known for its soul and r&b hits.

“I went down there and I demoed ‘Born a Woman,’ ” says Posey, “and it turned out kind of country-like, that session did, believe it or not, even though we did it in Muscle Shoals. So then I brought it back for Chips and played it for him, and he went crazy over the song.”

The original intent was to take the demo back to Nashville and pitch it to someone else as a country record, but Moman had other ideas.

“Chips said, ‘I’m going to cut this song with somebody, and you know it’s going to be a hit when I produce it,’” says Posey with a laugh. “So I knew instinctively, if I’m going to hit on this song I better let him record it.” They re-recorded the song in Memphis, with Moman producing, and it became a pop, not a country, hit.

As for the image of women in that song and others she cut at the time, Posey does not have a simple explanation.

First of all, she was focused on what might sell records: “I was so involved in music and what would be commercial and what wouldn’t be, I have no clue what the public was saying about women in general back then. When you’re in the music business, you’re in your own little world, you know. It was that way back then. Probably not so much today.”

But, she insists, those self-sacrificing women did exist: “I don’t think I believed it, but I lived it,” she says, referring to the portrayal of women in ”Born a Woman.” “I lived it through my mother. I had all the emotions down there already to sing the song and understand kind of instinctively what it was trying to say.”

It doesn’t help me, today, that Posey sees the song’s final pledge of fidelity as positive: “I think the women kind of liked that, too, because they end up winning.” Winning a man, I guess.

Perhaps Sandy Posey is a true voice of the ’60s. Today, we are conditioned to expect female singers to be independent, empowered voices, like Gretchen Wilson, Beyoncé, and Björk. Instead of rock & roll rebellion, Posey is the mouthpiece of the conservative majority, feminist awakening be damned.

“Born a Woman” garnered two Grammy nominations in 1966, competing against its opposite in Nancy Sinatra’s rebellious “These Boots Are Made for Walkin’ ” for Vocal Performance (Female)—which Eydie Gorme won for “If He Walked into My Life”—and for Contemporary (R&R) Solo Vocal, which Paul McCartney won for ”Eleanor Rigby.” She released four albums for MGM in the space of seventeen months.

You could easily create narratives, Broadway revue-style, of Posey’s mini-dramas from those albums: The stories would all start with the “Single Girl” (Posey’s second No. 12 hit, also written by Martha Sharp) alone in the big world who believes she needs a “sweet lovin’ man to lean on” even though she knows “all about men and their lies.” One plotline would lead her to finding a guy but being helplessly vulnerable and pleading, “Don’t Touch Me” unless you love me because I might not have self-restraint. The result: She’s on the street, asking “Hey Mister,” can you help me find the welfare line because this guy “took my love and then he walked on”? Or the even more troubling marriage story: I’m born a woman, born to be hurt, but I love my man and that makes it all okay because I’m a “One Man Woman” who will run to his side when he snaps his fingers, and even when our love is “Shattered” and I tell him I want to leave him, the minute he cries those unmanly tears, “I Take It Back” because “sometimes it’s better to be loved than it is to love.” “What a Woman in Love Won’t Do,” indeed.

There would be rare glimmers of freedom from the women who escaped, as in the sassy “See Ya Round on the Rebound.” But not many.

Of course, it’s not hard to create plotlines from any girl-group love songs of the era. The excellent four-CD, hatbox-shaped collection One Kiss Can Lead to Another: Girl Group Sounds, Lost and Found, which does not include any Posey songs but should, could provide fodder for a Faulknerian set of interweaving plots. What distinguishes Posey’s songs, however, is their self-awareness of the woman’s disempowerment. Unlike the archetypal girl-group song as defined in Jacqueline Warwick’s new study Girl Groups, Girl Culture, hers do not address “themes of special importance to teenage girls.” The point of view is not that of an innocent young girl naive in the ways of men, although Posey herself may have been that girl at the time. Instead, it’s an experienced woman who willingly and knowingly allows her man to walk all over her. And she likes it.

Since the songs Posey recorded are so aggressive in their submissive perspective—it is the overt subject matter, not a subtext that needs any deconstructing—the lyrics can overwhelm everything else. But these are, first and foremost, pop tunes, and they’re often simply great songs, if you define a song by its melody, vocal performance, instrumentation, and arrangement, those things that hit the ear before the lyrics hit the brain. It is easy to revel in a good song well-sung and well-played and not care, at least initially, about unpacking the content. Posey’s pure voice possesses a bit of twang, a lot of hurt, and a taste of easy joy, and she shifts easily among styles: girl-group insouciance juxtaposed with countrypolitan poise, Memphis r&b grit (although at the finest sandpaper grade) rubbing against classic pop buoyancy.

And the music! Chips Moman and his synergistic house band were riding a string of hits at American Studios, and Posey benefited from great songwriters—P.F. Sloan, Joe South, Doc Pomus, and John D. Loudermilk—as well as Dan Penn and Spooner Oldham (their “Hey Mister,” in particular, is a lost classic, a spare song that Posey sings in full vibrato).

No. 12 was the glass ceiling for Posey’s chart success: “I Take It Back” got there, too, but Posey never found that definitive tune to carry her to the top. Her songs often blended genres so that they did not fit comfortably into either the country- or the pop-radio format. She also did not tour much. Although the album covers sell her as confident and in command—dig that killer beehive on Single Girl!—Posey says she was anything but. She performed live on some package tours and made the circuit of television shows—with Sonny and Cher, with Neil Diamond, with Sammy Davis, Jr.—but she was more comfortable in the studio than on the stage.

“You know, I was so scared. I was so shy. I went right out of high school into the studio,” she says. “After I had my hits, I wasn’t prepared to be the professional that I saw everyone else being because they had worked [onstage]. I didn’t have anyone to tell me that as you work, you become better. I worked some, yes, but not enough to get established as an entertainer where I felt really comfortable on stage. I was more interested in recording; I loved working in the studio.”

Once her contract with MGM ended in 1968, Posey went back to session work, most notably for Elvis Presley on his 1969 Memphis recordings (she’s featured on “Mama Liked the Roses”) and on some of his early 1970 Las Vegas sessions, although she recorded her parts in Nashville (“That’s what we did in the South,” she says. “We went from Memphis to Muscle Shoals to Nashville and back”). She saw him perform at the Memphis fairgrounds when she was young, but she met Elvis only once, at RCA’s Nashville studios: “He was a perfect gentleman. Very nice. Very, very, very good-looking,” she laughs.

Posey found some success on the country charts in the ’70s with such songs as the maudlin “Bring Him Safely Home to Me” and slightly risqué ”Why Don’t We Go Somewhere and Love?,” both recorded with the noted Nashville producer Billy Sherrill. In 1974, she became a born-again Christian and turned to religious material. She recorded little in the ’80s and ’90s; her most recent release is 2002’s American Country Bluegrass. Living outside of Nashville, she is now married to Wade Cummins, a.k.a. “Elvis Wade,” the only Presley-approved Elvis impersonator, and she performs with him occasionally. She still sings her old hits.

“Oh yeah, I have to,” she sighs. “Everybody always asks for either ‘Born a Woman’ or ‘Single Girl.’ ” Now, she prefers the Penn-Oldham songs such as “Hey Mister” and “Are You Never Coming Home?” “I wasn’t crazy about any of my hits at all,” she says, calling them “bubblegum.”

There’s nothing wrong with bubblegum—some would argue that all pop music is bubblegum—but Posey’s songs can’t be dismissed as typical bubblegummy superficial pleasure. They depict a real world that’s full of compromise and pain, a world that exists in the past and the present, where women compromise themselves for men. That’s Posey’s argument:

“There’s a lot of women that will do that. They live that way. And more so back then than today. Women are more knowledgeable and getting more help than they did back then. But you know, even today, it’s a man’s world, and, you know, God created man to be the leader of the home. We have a tendency to swing too far to the left or the right, and we’re still looking for a balance. The Bible says that God hates a false balance, and where men and women are concerned and even black and white, we’re still looking for that balance in the middle somewhere, to feel better.”

Sandy Posey’s songs depict a very imperfect world, although they don’t do much to challenge its injustices and inequities. That’s why they present a challenge themselves. Their nearly masochistic conservatism runs contrary to present-day expectations. These complexities, however, can offer their own rewards for a listener. I’m drawn to these songs for their strangeness, for their alien qualities, but ultimately because Posey’s seductive vocal performances transcend the subject matter—she sings the hell out of these songs, which almost renders the sociological implications moot. Almost.

Sometimes it’s better to be unsettled than it is to love.