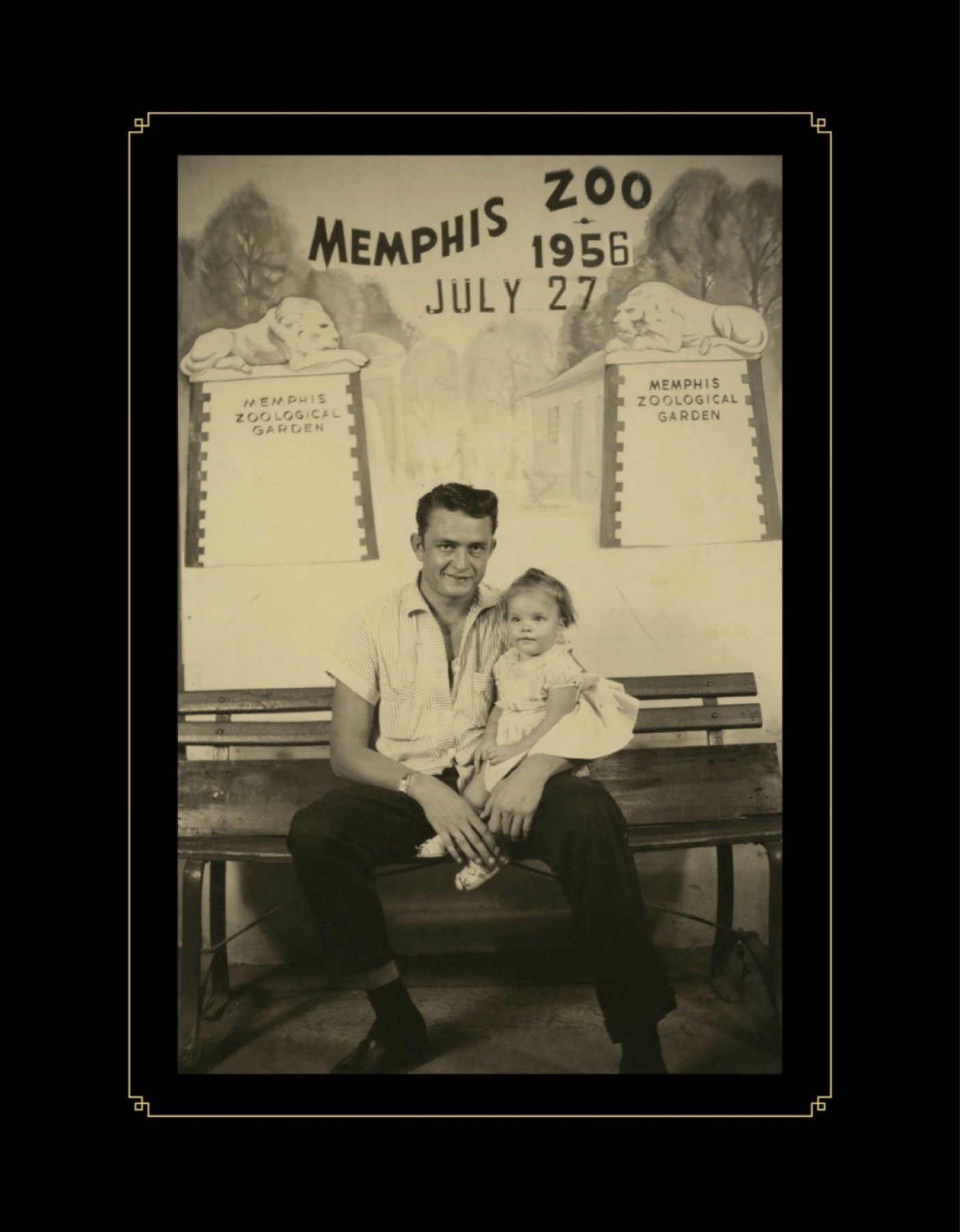

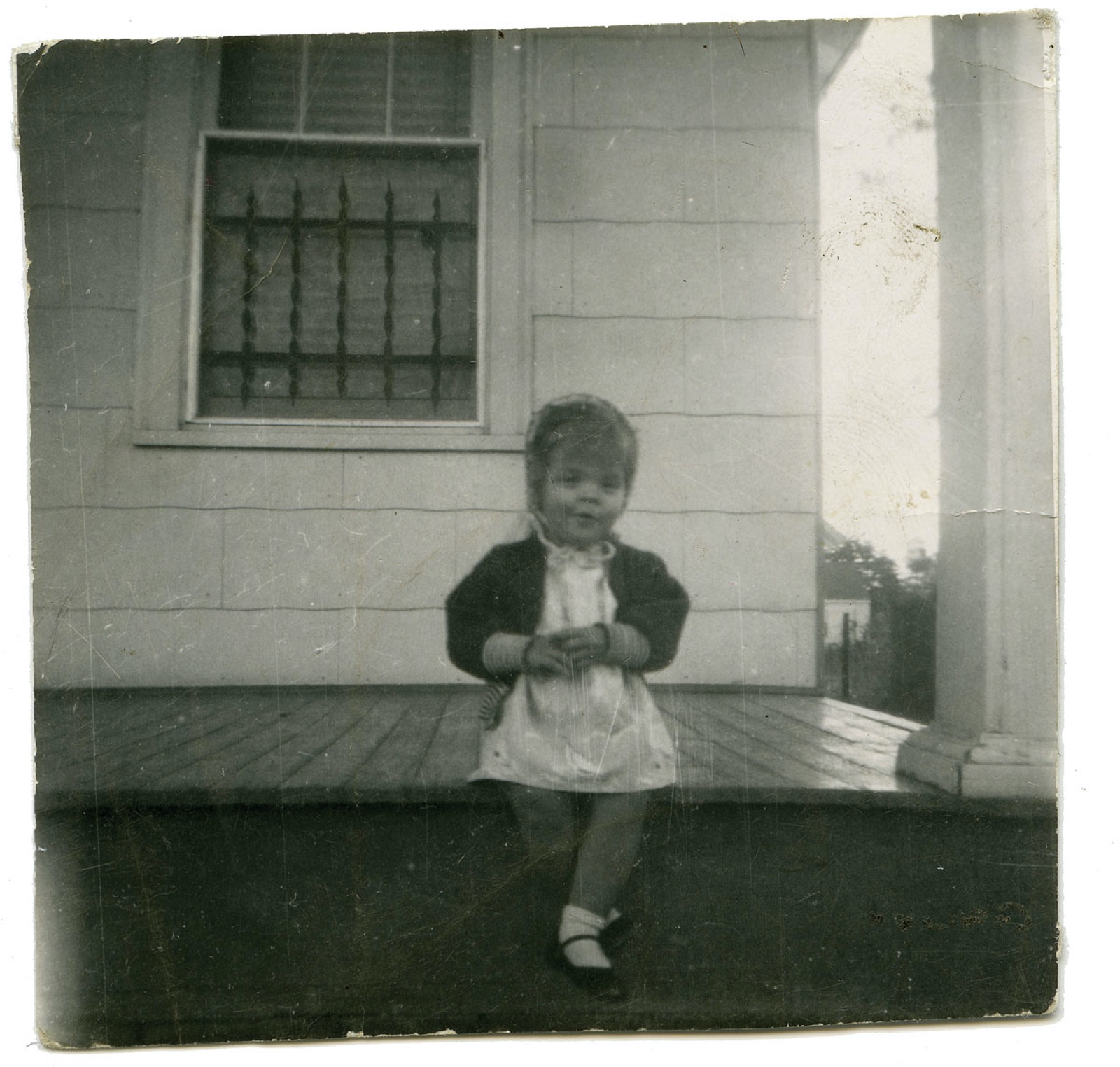

Photographs courtesy of Rosanne Cash

Long Way Home

By Rosanne Cash

I was born at St. Joseph’s Hospital in Memphis on a muggy evening just before eight p.m. in late May 1955. Two months later, my father’s very first single, “Hey Porter,” backed with “Cry, Cry, Cry,” was released on Sun Records, a small record label and recording studio at 706 Union Avenue in downtown Memphis. Sun was owned by Sam Phillips, a young music entrepreneur, recording engineer, and record producer. The building still stands, essentially as it was in the early 1950s when my dad, Elvis Presley, Jerry Lee Lewis, and Carl Perkins created their first recordings. Now it is a thriving tourist destination but still a fully functioning recording studio. Musicians come from all over the world to genuflect at the altar of the birthplace of rock & roll.

During my mother’s pregnancy, my dad made half-hearted attempts to work as a salesman for the Home Equipment Company on Summer Avenue in Memphis. He was also studying to be a disc jockey. My parents lived in a tiny, bare apartment within walking distance of Dad’s workplace. His lackluster performance as a salesman may have had something to do with his reluctance to cajole or manipulate a sale. He once even talked a potential customer named Pat Isom out of buying a refrigerator in the store because it was “too expensive” and didn’t carry a good warranty. Pat was so impressed with Dad’s honesty that she engaged him in conversation and found out that he and his pregnant wife, Vivian, needed a new apartment that didn’t have stairs. Dad was afraid my mom might fall in her delicate condition, so Pat offered my parents half of her duplex at 2553 Tutwiler Street in mid-Memphis. It was also a short walk from the Home Equipment Company and about five miles from Sun Records, though at that time Dad didn’t know how large Sun would figure into the next few years of his life.

In the warm spring before I was born, my mother told me that she would sit on the porch with a washbasin of cherry tomatoes in her lap and eat the entire bowl, staring out onto bleak Tutwiler Street, missing her parents, trying to fit into her new life. Pat and her husband, whom everyone referred to as Charlie B, lived in the other half of the duplex. After I was born, Pat and Charlie B were so taken with me that they cut open a little doorway between the two apartments so I could crawl back and forth. My mother always said that my birth “awakened the instinct” in Charlie B, who had no interest in becoming a father until Pat pulled me onto her ample lap and rocked me to sleep every day to give my mother a little break. Apparently, it was my presence that inspired Charlie B to fatherhood.

My parents were poor, and during her pregnancy my mother had only two dresses that fit. When I was born, my mom’s younger sister, my Aunt Sylvia, came straight from her high school graduation in San Antonio to help out. She said that there was so little money that she had to use her graduation money to pay for groceries.

Everything changed so drastically in the next three years that my parents, only twenty-one and twenty-three years old, must have been dizzy from trying to understand their own lives. Our little family grew quickly. When my mother went to the doctor for her six-week checkup after giving birth to me, she was already pregnant with Kathy, who came along ten months and twenty-three days after me. Cindy was born two years later. Meanwhile, my father had a hit record on his very first release and was suddenly a sensation, performing around the South, gathering fans, including, to my mother’s great alarm, hordes of young women who fawned and swooned from his very first performance at the Overton Park Shell in Memphis. By 1958, my dad, with his sultry good looks, had offers to appear in movies, so we left Memphis for Southern California. Three years later, Tara was born.

I have only one memory of living on Tutwiler Street. There was a candy store at the end of our block, and I remember walking hand-in-hand with my dad to the little shop on the corner and being allowed to choose any candy I wanted. My cousin Jackie Cash, daughter of my Uncle Roy, has a more potent memory. She was eight years old, visiting us in the duplex when I was a baby, and sitting next to my dad on the sofa while he played guitar and fooled around with lyrics. She recalls him yelling to my mother in the kitchen, “Honey, listen to this,” and he sang,“But that train keeps a’rollin’/ on down to San Antone.” Alas, I don’t remember that at all.

Memphis was bursting with music. It was a hot stew of musical urgency: blues and Southern gospel, rock & roll, the “hillbilly” music that came to be called “country,” and the new strains of rockabilly. At the same time, at the other end of the spectrum, Tommy Dorsey was performing at the old Claridge Hotel the year I was born.

Radio station WMPS played the Louvin Brothers, and WHBQ had DJ Dewey Phillips, whose show “Red Hot & Blue” was enormously popular with young people. After my dad’s first single was a hit, he did an interview with Dewey from the Chisca Hotel, a popular gathering spot. After listening so faithfully to Dewey, this must have been a huge moment for Dad. WDIA employed the first black disc jockeys, including Rufus Thomas and a guitarist named Riley B. King, who played live on the air and soon came to be known as B.B. My parents listened to all three of these stations, and absorbed equal parts of the blues, Appalachian harmony, Southern gospel, and rock & roll. All those strains imprinted themselves in the most profound way, and my dad became who he was out of that brilliant amalgamation.

My parents’ best friends were Marshall and Etta Grant and Luther and Birdie Perkins. Marshall and Luther had been mechanics who worked at the same car dealership as my Uncle Roy, who was also a mechanic. Automobile Sales, a large DeSoto and Plymouth dealership, was at 309 Union Avenue, just down the street from Sun Records at 706 Union. When my father was discharged from the Air Force and returned to Memphis, my uncle Roy picked him up at the bus station and then took him over to Automobile Sales to introduce him. Marshall told me that when my dad walked into the mechanic’s bay he looked up, saw a lanky, dark-haired young man standing in the doorway, and that the hair on the back of his head stood up and chills went down his back. He knew.

“Roy says you boys pick a little music,” Dad said to Marshall and Luther. “Very little,” Marshall answered. “Maybe I can pick with you sometime,” Dad responded. And that was the beginning.

Marshall and Luther and Dad gathered at Marshall and Etta’s home at 4199 Nakomis Ave. to play primitive rhythms on three guitars and sing old country and gospel songs, and a little band was formed. It was decided that Marshall should play bass, so he taught himself how to pick out a boom-chicka-boom rhythm on a stand-up bass. Etta, Birdie, and my mom played cards in the kitchen while the men practiced and began to forge a style out of their limitations.

My mom and Etta became like the closest of sisters. They were always together, and then when Dad, Luther, and Marshall went on the road, Mom and Etta were close companions and a two-woman support group. When Dad and the Tennessee Two started performing in the area around Memphis, Dad would leave my mom and me and later Kathy at the Nakomis house with Etta. We’d go to bed, and Dad would come to get us after the show, late at night or in the early morning hours, to take us home to Tutwiler, then to a new house on Sandy Cove, and then eventually to an even nicer house on Walnut Grove. Marshall said he always thought I was asleep when Dad lifted me onto his shoulder, but then he’d see my little hand pat Daddy’s back as we walked to the car. I suppose I already knew that a touring musician had a hard life.

Marshall and Etta moved to Hernando, Mississippi, in the 1970s, but they never gave up the house on Nakomis. It became a place of memories for them, filled with souvenirs from the decades Marshall and Dad were on the road together, closer than brothers, from the first rudimentary attempts at music, through the Sun Records years, through staggering success and inconceivable fame, my dad’s drug addiction, my parents’ divorce, Dad’s recovery from addiction and chronic relapses, a devastating lawsuit between them, and eventually, sweet reconciliation in their later years. One of the few times my dad got really angry with me was when I came to Marshall’s defense during that lawsuit. Dad forgave me quickly, however, in a letter he wrote me saying that he knew my instincts were those of compassion.

The drama, love, schisms, and reconciliations of Dad and Marshall’s relationship were played out for the most part in public, but no one saw the heartbreak of Mom and Etta’s inevitable separation after my parents’ divorce. Etta still talks to me about Mom, how they loved each other; how, when we moved to California, Etta put a stool in the hall outside her kitchen next to the wall phone so that she could sit and have long conversations with my mother every day. In one conversation Etta recalled my mother saying, in reference to the Carter Family traveling with my dad’s show, “Etta, I’m a little concerned about Anita.” Etta said, “Vivian, you ought to be a little more concerned about June.” Prescient, to say the least.

Vivian Cash with Rosanne, 1956

Vivian Cash with Rosanne, 1956

Marshall and Etta were married sixty-five years. Etta told me that every morning of their lives, when they woke, they asked each other, “What’s the temperature, darlin’?” It was a solid, practical way to start the day. They saved everything. Everything. Ticket stubs, concert programs, early reel-to-reel tapes, instruments and amplifiers, kitschy gifts from the road, letters, itineraries, set lists, receipts, photographs, and more. In their old age, they would drive from Hernando to Memphis just to sit in the living room and reminisce—and Etta, in her late 80s, still talks about moving back to Nakomis permanently. They weren’t necessarily happy memories, in their old age, in the Nakomis living room. Marshall called me every couple of months in the last few years of his life to tell me the old stories, over and over again, and he invariably began to cry before we got to the end of the conversation. He tortured himself over his inability to keep my dad off drugs. He agonized over the lawsuit. He couldn’t bear to live with his memories of the best years of his life, those years of playing music with the man he loved more than a brother, in some ways more than himself, and know the good times were gone forever. He told me secrets, gave me an objective view of my parents I never could have had otherwise, and loved me like a daughter. He never got over my dad’s death, not for a second.

In August 2011, he came to Jonesboro, Arkansas, to play the upright bass in a concert to raise funds to restore my dad’s boyhood home, an hour from Memphis, in Dyess, Arkansas. I saw him in rehearsal that day, holding that bass guitar, an image as familiar as my own reflection in the mirror. I sat arm-in-arm with him that night in the hotel lounge and reveled in the love of a man who was the third person to hold me when I was born. He had a brain aneurysm that night, and died three days later.

Etta’s Tune

(Rosanne Cash/John Leventhal)

What’s the temperature, darlin’?

A hundred or more

Horses pawing at the dust

Violets wilting by the door

But you pour the strongest coffee

And I’ll take the battered wheel

We’ll drive straight down the river road

Spread a blanket on the hill

What’s the temperature, darlin’?

Now don’t stare into the past

There was nothing we could change or fix,

It was never gonna last

Now don’t stare into those photos

Don’t analyze my eyes

We’re just a mile or two from Memphis

And the rhythm of our lives

A mile or two from Memphis

And I must go away

I tore up all the highways

Now there’s nothing left to say

A mile or two from Memphis

And I finally made it home

There were days you paced the kitchen

There were nights that felt like jail

When the phone rang in the dead of night

You would always throw my bail

No you never touched the whiskey

And you never took the pills

I traveled for a million miles

While you were standing still

What’s the temperature, darlin’?

As the daylight fades away

I’ll make one last rehearsal

With one foot in the grave

We kept the house on old Nakomis

We kept the polished bass guitar

We kept the tickets and the reels of tape

To remember who we are

A mile or two from Memphis

And I must go away

I tore up all the highways

Now there’s nothing left to say

A mile or two from Memphis

And I finally made it home

What’s the temperature, darlin’?

In 2012, my husband, John Leventhal, our teenage son, Jake, and I went to Memphis to show Jake the city of my birth and the studio where his grandfather began his career. We went to Sun Records and there was a long line of tourists waiting to get in and another large group already inside. Jake and I waited around the side of the building at the empty picnic tables and John slipped in and asked the manager if we might go in the back way for a private visit. She let us in through the control room and we waited until everyone had cleared out. I have a picture of my son, lost in thought while strumming a guitar, standing in the empty studio in front of a larger-than-life-size photo of my dad, Elvis, Jerry Lee, and Carl. Jake was four years old when his grandpa died, and he has only a few blurry memories of him. If my dad, the twenty-three-year-old new father, nervous as a cat at his first recording session in that very room, could have imagined his thirteen-year-old grandson standing there next to him, gazing around with the confidence of a child who doesn’t yet feel the weight of his own family history, would the world have stopped spinning for a moment to let him take it in? It did for me.

After leaving Sun, we walked to the nearest trolley stop, past a poster advertising radio station WDIA: 50,000 WATTS OF GOOD WILL. The Memphis trolley service was discontinued in 1947, and was replaced by trolley buses, which ran along the same tracks and used the electrical wires of the old trolleys. In my fifty-eight years, I never once thought about my mother taking the trolley bus, or thought to ask my parents if they did. My parents had a car but gas was expensive and my mother was left at home while Dad worked, so she must have occasionally taken the trolley bus downtown to do her errands or to meet Etta for an ice cream at the Woolworth’s counter, and buy a lipstick or window shop, or go to the giant Sears Crosstown building on North Watkins Street to pick up her catalog orders, or maybe just to take me for a ride.

We waited on the old platform. When we got on the trolley bus, I was surprised to see original oak seats, burnished a deep gold. The riders got up to ring an old-fashioned bell in the center of the car when they wanted the driver to stop. Someone stood to ring the bell and that’s when I got an image of my mom. I looked at Jake, who was dreamily staring out the window, and I saw my mom, pregnant with me, a twenty-one-year-old devout Catholic, staring out into a more contained, predictable downtown Memphis, going to meet her friend, wondering if she was carrying a boy or a girl, if they would have money, if life would be easy or hard, if there would be more children, if a man could make a living making music—what the future would hold.

50,000 Watts of Common Prayer

(Rosanne Cash/John Leventhal)

It’s a hard road, but it fits your shoes

Son of rhythm, brother of the blues

The sound of darkness, the pull of the yoke

Everything is broken and painted in smoke

But there’s a light on Sunday

A new old desire

The sound of the whistle ’cross radio wires

Love in your future

I’ll wait for you there

With 50,000 watts of common prayer

We’ll be who we are, and not who we were

A sister to him, a brother to her

We’ll live like kings without any sin

Redemption will come

Just tune it on in.

There’s a light on Sunday

A new old desire

The sound of the whistle ’cross radio wires

Love in your future

I’ll wait for you there

With 50,000 watts of common prayer.

That was my first Tennessee: Memphis, 1955 to 1958, the Tennessee that got imprinted on my soul, and that made me feel that a part of me was Southern, even though I spent the next fifteen years in California.

My second Tennessee began in 1967, when I was twelve years old. My parents had just separated the previous winter, and that first summer my mom let my sisters and me go to Tennessee to spend several weeks with my dad. He had just bought the big house on Old Hickory Lake in Hendersonville, about twenty miles from Nashville.

Dad was just emerging from the depths of his drug addiction, but he was clean and sober, if gaunt and a little shaky. He and June were not married yet, but she and her daughters, Rosie and Carlene, were around a lot and we befriended our soon-to-be stepsisters. The next several summers were glorious, each better than the one before. Dad had a little speedboat, and he taught all of us to water ski. He was the most patient teacher in the world. We jumped in the water, hooked our feet into the skis, and he gunned the engine. We fell and fell and fell. And then, eventually, we got up and he whooped and waved his arm at us as he pulled us around the lake. We did this every day for hours. Once I was sitting in the boat with him while he pulled one of my sisters up on the skis when the glove box popped open and money—bills of all denominations—flew out and away. My dad glanced at the currency as the wind carried it out of the boat, but never looked back, never said a word. That gave me an insight into my dad’s relationship with money: He let it fly and never looked back.

Every summer, he made peach ice cream on the lawn, with peaches from his own orchard. He hand-cranked the old-fashioned ice cream maker until his arm was surely aching and stiff. He never complained. He set firecrackers off in the yard while we ate huge bowls of his homemade ice cream. He took us riding in his jeep on the back roads, picking up his sister Reba’s kids and June’s sister Helen’s kids on the way, until there were six, seven, or eight kids recklessly piled in the back. He rented the skating rink so we could skate in private, because he was so recognizable at this point that he had not a single moment’s peace when he was out in public.

I had my first boyfriend the summer I was fourteen, and I stayed up all night talking to him on the telephone. My dad, incredulous at breakfast, said, “What could you possibly talk about for eight hours straight?” I couldn’t recall.

Johnny and Roy Cash with their wives Vivian and Wandene, 1956

Johnny and Roy Cash with their wives Vivian and Wandene, 1956

Dad had a farm in Bon Aqua, Tennessee, about sixty-five miles from Nashville, which my brother owns now, and we spent part of the summers there, picking wild blackberries and playing music on the porch. My sisters and I, once we learned to drive, would sneak off to the country psychic, an ancient woman way out in the sticks who had a card table set up inside her rustic cabin, just off an empty highway. Cars were lined up on the shoulder of the road, and you were expected to wait in your car. As soon as one middle-aged housewife came out of the cabin, the one in the next car went inside. Carlene, Kathy, Rosie, and I were by far her youngest clients. She read regular playing cards. When I was seventeen, she told me I was going to win something that fall, and that my grandfather would die. Sure enough, I was elected homecoming princess that November at school and my mom’s dad died very unexpectedly. I didn’t go back to her the following summer.

The meals were epic. Cornbread and biscuits, chicken and dumplings, fried tomatoes and okra and chicken, greens with hamhock, coconut pie, chocolate pie—these were the staples. Dad had the best Southern cooks in the world, none better than my grandmother Carrie Cash, who lived just up the road with my Grandpa Ray, and whom we visited daily.

The summers were hot and lush and my memories are not tinged with a single regret, which is more than I can say for almost all my other memories. Those summers were pure, and they healed broken family connections and forged new bonds, opening the channels of love again, all through the pleasure of the senses and the joy of happy unorganized recreation.

When I was twenty years old I had been living in the house on Old Hickory Lake for two and a half years. I squeezed in a year at Volunteer State Community College while still traveling on the road with Dad and June, studying music theory and English. That year I moved away to London to grow up and find out who I was apart from the expansiveness of a life I was borrowing, not one I owned, and when I came back to the lake house at twenty-one, I was moody and restless. I put in a year at Vanderbilt University and then went back to California. The intensity and beauty of those years, basking in my dad’s love and rambling around the edges of the huge life he lived, from 1967 to 1978, is my golden Tennessee, the Tennessee of childhood dreams, when my own life seemed so big I could not fill it and love grew of its own accord.

Rosanne and Kathy Cash, 1959

Rosanne and Kathy Cash, 1959

In 1981, after making a record in Germany, and making another record in California with Rodney Crowell, I married Rodney and we started a family. We bought a house in Malibu Canyon. One morning our friend Hank DeVito, who lived near us in Los Angeles, got up and on a whim flew to Nashville. He looked at an expansive and beautiful log house in Franklin, twenty miles from Nashville and the site of one of the bloodiest battles of the Civil War, and impulsively bought it. When he came home to gather his belongings, he walked into our kitchen and tossed a real estate guide on the counter. I opened it up to a picture of another beautiful log house, a few miles from Hank’s, in a suburb of Nashville called Brentwood, and I said, “If I were going to move to Nashville, that’s the house I’d want.”

We did virtually the same thing as Hank. I flew to Nashville without Rodney, saw the house, described it in detail over the phone, and he said yes. We bought it.

I didn’t think it through.

I arrived in a nice, upper-middle-class suburb to find a lot of ladies who lunched at the country club and went to fancy churches; they wore carefully attended hairdos and big jewelry. My hair was a bright eggplant color, I had a big city edge, and I eschewed both religion and the country club. I did not fit in, to say the very least. I obsessed about what I couldn’t do or get in Tennessee. I asked the gardener if he could plant some bougainvillea around my house. He looked at me with bemusement and said, “You’re not from around here, are you?” I stiffened my spine in line at the movies, when I could hear whispers behind me about my hair color and my “army boots.” I was shocked at the magnitude of the loss I felt for the ocean. I began to feel acute self-consciousness and unrest. I dreaded going out of my house.

I was also sort of famous, particularly in Nashville, where I had three number-one country records in a row in 1981 and 1982. There was a lot of curiosity—and some resentment—directed toward me during this period. I didn’t know how to fit in, and many people in the industry took that to mean that I didn’t like or respect them. I had become interested in cutting-edge Japanese clothing designers, and at one multi-artist benefit show at the new Grand Ole Opry I wore a hot pink Comme des Garçons jacket made of parachute material with hugely exaggerated shoulder pads. I was introduced, walked out on stage, and the audience tittered. I was confused. The host of the show said, “What football team do you play for, Rosanne?” I was speechless with embarrassment. My confidence began to erode.

I eventually settled in, somewhat. My kids went to school and I met other parents, and I went to parties and industry functions, and became involved in a tight community of other musicians and songwriters. What I wanted, most of all, was to be a great songwriter, and there were many to admire and learn from in Nashville. I made friends. The tension eased, but never entirely.

By 1989, I was about to crack from pressures I couldn’t even fully acknowledge. Rodney and I didn’t seem to share a vision for our future. We began to want very different things, and I felt I couldn’t live in Nashville anymore. My record label made it clear that they weren’t interested in the work I eventually wanted to do. I felt suffocated. We left the log house in Brentwood and moved to a big house on Franklin Road in Nashville. Tour buses went by and the operators told the tourists that the big dark-green fence around our house was black, and that my dad, the Man in Black, had bought it for us to thank me for recording one of his songs. It seemed to be a story that had a lot of appeal, so the operators and tourists alike willfully ignored the fact that the fence was not actually black. I had an assistant, a housekeeper, a five-carat diamond ring, a 6,000-square-foot house, a lucrative recording contract, and a pile of number-one records, and yet I was deeply unhappy. My marriage was clearly not working. Nothing was working.

I met John Leventhal. I loved him the instant I saw him. Rodney and I both knew that our time was up, and we went hand in hand to the divorce lawyer. I had enough success that it gave me leverage to move on to the work I really wanted to do. I had made friends in Nashville, some of whom are still very dear to me. I developed specific disciplines in songwriting and recording that have proven critical to the work I do now, and the work I want to do in the future. Oddly, my separation from the ocean, my spiritual touchstone, caused me to seek spiritual sustenance in other areas, and though most of those pursuits proved to be shallow and short-lived, the seeking itself had a great effect on me. I learned to take pleasure in nature and normality. I moved to New York. I married John Leventhal.

That was my hardest Tennessee.

World of Strange Design

(Rosanne Cash/John Leventhal)

Well, you’re not from around here

You’re probably not our kind

It’s hot from March to Christmas

And other things you’ll find

Won’t fit your old ideas

They’re a line in shifting sands

You’ll walk across a ghostly bridge to a

crumbling promised land

If Jesus came from Mississippi

And tears began to rhyme

I’ll have to start at the beginning

This is a world of strange design

Well, I’d like to have the ocean

But I settled for the rain

I humbly asked for true love

There was such a price to pay

’Cause this room was filled with trouble

And sacraments deceived

Now I’m a jewel in the shade

Of his weeping willow tree

If Jesus came from Mississippi

And tears began to rhyme

I’ll have to go back to the beginning

This is a world of strange design

We talk about your drinking

But not about your thirst

You set off through the minefield

Like you were rounding first

So open up a window

And hand the baby through

Point her toward the ghostly bridge

And she’ll know what to do

If Jesus came from Mississippi

And tears began to rhyme

We’ll have to start at the beginning

This is a world of strange design

I’ve been a New Yorker for more than twenty years, but my memories of the South are potent. Some are truly mine, and some I have borrowed. Tutwiler Street and Nakomis Avenue, the corner candy store and the tired shoulder of a big man. The shining dark-blond wood of the trolley buses, the big silver ribbon microphones in Sun Studios, the marquee of radio station WDIA. The dollar bills that floated over Old Hickory Lake, the old country psychic who scared me because she saw my real life, the whispered voices in the movie line, and the dark green fence on Franklin Road. These are what I have, along with the unchanging verdant landscape, sprinkled with lightning bugs. These memories form a backdrop to a stand-up bass and an acoustic guitar, an image that evokes both the past and the future.

I was in East Tennessee last summer, sitting in a rocking chair, watching the mist drift so gently over the rounded hilltops of the Smoky Mountains. As I gazed at the soft blue-white smoke floating across the deepest, darkest green, which settled into the meandering contours of the hills and creeks and fields, I felt my heart crack a little with love for Tennessee. It was like discovering some new piece of information about your parents that you can only understand as an adult, after they are gone, something beautiful that you suddenly realize they have passed on to you without your knowledge. That gift, in this decade of my life, feels so far from Tutwiler Street, but I see that the love has always been there. This is my real Tennessee, my bowl of cherry tomatoes, my playing cards laid on the table, my son and father in the same room, where money doesn’t matter. My Tennessee that lasts forever.

The Long Way Home

(Rosanne Cash/John Leventhal)

Dark highways and the country roads

Don’t scare you like they did

The woods and winds now welcome you

To the places you once hid

You grew up and you moved away

Across a foreign sea

And what was left was what was kept

Was what you gave to me

You thought you’d left it all behind

You thought you’d up and gone

But all you did was figure out

How to take the long way home

The Southern rain was heavy

Almost heavy as your heart

A cavalcade of strangers came

To tear your world apart

The bells of old St. Mary’s

Are now the clang of Charcoal Hill

And you took the old religion from

The woman on the hill

You thought you’d left it all behind

You thought you’d up and gone

But all you did was figure out

How to take the long way home.

Rosanne Cash, Tutwiler Street, 1957

Rosanne Cash, Tutwiler Street, 1957

Enjoy this story? Subscribe to the Oxford American.