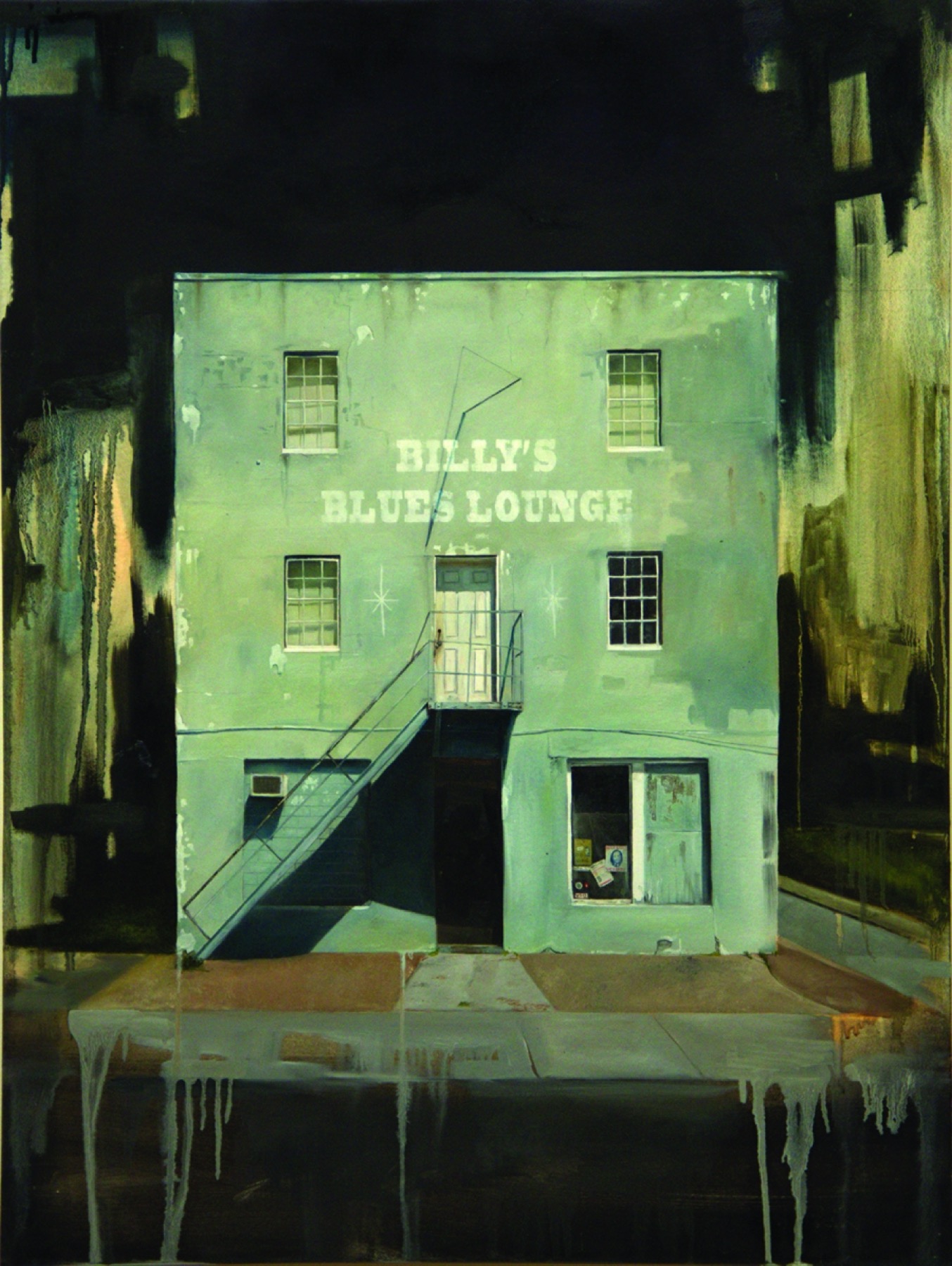

“Billy’s” (2013) by Jared Small. Oil on panel. Courtesy of David Lusk Gallery

Sing Like a Mountain

By Bill Bentley

Grown from the bounce and bustle of rhythm & blues, peppered with a sanctified high calling from the church, rubbed up against on jukeboxes, and piping from radio stations stretching across the country, soul music became a lifeline for listeners in the 1960s. These songs not only saved lives, they inspired the faithful to search for love against all odds. That’s where Ray Charles, Bobby “Blue” Bland, James Carr, Otis Redding, Percy Sledge, Wilson Pickett, and so many others excelled. Their music was a sacred trust in African-American communities, and once it started seeping into the everyday life of white America, the roots of integration were planted. Because soul music brought the two races together, breaking down long-constructed barriers in a way that has still not been equaled. In those rushing sounds of wide-open emotion and gravity-defying rhythms, listeners found a peaceful ground, a place where the harsh reality of the outside world did not intrude—if even just for the three minutes of a 45 record. Whether broadcast over the airwaves or heard inside nightclubs and concert halls, soul songs created a soundtrack of harmony.

There is a name buried deep inside the treasure troves of long-dormant record labels, a name that is whispered among soul music’s true believers: O. V. Wright. He sang like God was sitting on his shoulder, urging him to bear witness to the pain that comes with hardship. In doing so, Wright created a path to another world by giving hope to listeners struggling with day-to-day life. Wright was born in 1939 in Leno, Tennessee, not far from Memphis. On Sundays he would make his way to a small church, the most public place that an African American could truthfully call home. He traveled throughout the South as a gospel singer, working a well-worn circuit. But though Wright’s heart was filled with peace when he sang spirituals, he was also aware that the world outside the church would someday come calling, enticing him to turn his back on the Lord and venture into the wilderness.

That world beckoned so loudly that Wright left acclaimed gospel groups such as the Five Harmonaires, the Spirit of Memphis Quartet, the Highway QCs, and finally the Sunset Travelers to pursue a career in soul. When he decided to record secular music, Wright exited the church for good. And in that realm, those who left turned their backs on God—a trespass God would not forget. The two sides of music would not be merged, and those on the side of the church cast the wanderers as traitors. No doubt this caused O. V. Wright a lifelong despair. Some might say he never really got over it. The scars of being an outcast lasted a lifetime.

I first listened to O. V. Wright in 1964, when his song “That’s How Strong My Love Is” brought the singer into my heart forever. It was the B side of a Goldwax Records single, but to me it was a calling card to eternal warmth, a map to a life of enchantment. Wright’s voice captured the eternity of all great gospel music, but he applied it to the wonder of romantic love. But just as Wright’s success with Goldwax seemed imminent, his old label boss, Don Robey, put a claim on his talent; Duke-Peacock Records still had the singer under contract with the Sunset Travelers, so Goldwax withdrew “That’s How Strong My Love Is” from distribution. In 1965, both Otis Redding and the Rolling Stones recorded the song, and Wright must have felt as though he’d been stabbed in the stomach. As for me, a Houston teenager who spent nights sitting in a car outside Duke-Peacock’s office at 2809 Erastus Street in hopes of seeing O. V. Wright leave the building, I thought of him as a singing angel visiting our city.

It wasn’t long before a devastating string of recordings for Duke-Peacock’s subsidiary Back Beat Records began to make their way onto the rhythm & blues charts. Songs like “You’re Gonna Make Me Cry,” “When You Took Your Love from Me,” “Born All Over,” and “Ace of Spades” established O. V. Wright as the next in line to the soul throne, someone who could do what Ray Charles had done but with the stamp of Southern grit. Wright’s voice carried the weight of a troubled traveler: there was a dark desperation underneath the beauty of his singing style, like he was alone at the edge of the world with no way back. No one else then could so affectingly combine a fear of emptiness with the promise of salvation, or inhabit the despair of living without hope. On “A Nickel and a Nail,” Wright expresses the apex of that hurt: “I once had love and plenty of money / someway somehow Lord knows I failed / now all I have in my pocket / all I can give account of is a nickel and a nail.”

While Wright’s songs became hits on black radio stations and Duke-Peacock proved their marketing clout, the man himself remained an enigma. He was the Lonesome End of soul music, left out of the huddle while Bland, Redding, Pickett, Sledge, and other chart toppers attained national stature. Rumor had it Don Robey told Wright that “he was too ugly to tour,” an entirely unfair cut considering the singer had the look of a high school science teacher with large black-framed glasses and a serious face. He might not have been Otis Redding or Wilson Pickett, but Wright carried himself with the dignity of someone who knew his place in the world.

In 1966 I discovered Wright would be appearing at Houston’s Cinder Club, a B-list spot that featured mainly local artists. To me, this was better than if Santa Claus and the Pope had been coming to town at the same time. The Cinder Club was a small room, and on the first night of a three-day run, O. V. Wright walked onstage like he’d been born there. He assumed command of a seven-piece band that had the kind of road-worn mustiness that comes from traveling in old Cadillacs and living on cold plates of day-old fried chicken; as I watched them, I felt like I was peeking behind a show business curtain and discovering the endless ache of working the chitlin circuit on nickels and dimes. Yet every single song was an epic display of Wright’s power and virtue. His soul hits, “I’d Rather Be Blind, Crippled & Crazy,” “Eight Men, Four Women,” “I’ve Been Searching,” and the especially stunning “A Nickel and a Nail,” followed one after the other, an unfaltering series of Muhammad Ali knockout punches. Wright drove the fifty people in the audience to delirium; he was pouring water on weary travelers who had walked out of a yearlong trek across the desert. Quite simply, he set the faithful on fire.

Wright made Houston his home away from Memphis, and there would be many such nights as this. He never moved up to the Pladium Ballroom or multi-artist extravaganzas at the Coliseum, but I didn’t care. O. V. Wright was mine, and in his performances I found a life-changing strength. Two years later, when Dr. Martin Luther King Jr. was assassinated, it was clear that whites and blacks would not be going to the Promised Land together anytime soon, that the soul music brotherhood was not enough to make it happen. Looking back now, all these songs and nightclub shows shimmer with the glorious glow of fleeting love, and I hold on to my memories of those events like a life preserver. It was a musical dream that painted visions of a different world, one where all people could live together in peace. O. V. Wright cast a blanket of inclusion over his audience and made us feel that our differences were much smaller than the binds of togetherness. At the time, it seemed that we could walk hand in hand on the road ahead.

On a trip to Memphis twenty years ago, inspired by so many of O. V. Wright’s songs flooding my memory, I went to Royal Studios on South Lauderdale Street, where the artist cut those inspired Back Beat recordings. A sonic glow hovered around the studio, but I was looking specifically for the singer’s spirit. I knocked on the door and waited, and there was silence for a few minutes before the door slowly opened and a small man with mesmerizing eyes inquired after what I wanted. I asked if I could look at the studio, and he somewhat suspiciously invited me into the front room. There was only a desk and a couple of chairs, with a light bulb hanging down on a wire from the ceiling. I soon realized this was Willie Mitchell, the record producer behind Al Green, Ann Peebles, Otis Clay, and Syl Johnson. He answered my first questions with short, rather indirect responses—until I asked about Wright, whom he also produced. A huge smile spread across Mitchell’s face, and his eyes began to glisten. Without missing a beat, he said, “That’s the greatest singer I ever worked with.” For the next hour, he discussed his passion for the music the two men had made together. Mitchell unlocked a secret door—how do such life-affirming moments find us? He described the way Wright would stand dead still, waiting for an otherworldly presence to take over his being. When he was filled up, the words would come out, lifting Wright’s core into a higher place.

When I returned to my home in Los Angeles, where I had moved in 1980 in part to meet and interview Big Joe Turner, Ruth Brown, Pee Wee Crayton, Charles Brown, Roy Milton, Lowell Fulson, Roy Brown, and other r&b luminaries, I told Ry Cooder about my search for O. V. Wright. He lit up right away, speaking in hushed tones of his own love for those chilling records. Cooder described how he had called Wright’s house in Memphis in 1980 in hopes of working with the singer. But he was a day too late. Wright’s wife gave him the news that “O. V. done passed.” We both shuddered when Cooder told the story, and I remembered the hard-hitting lines of a classic Wright song: “I am so miserable I am so tired / oh I just sit on the Mississippi River and watch the fish swim by / my life is so confused but I don’t want to die / I want to go to heaven but I’m scared to fly.” Have mercy.

Sometimes music that heals all wounds demands a high price from its practitioners. In order to testify so strongly, they may have to take the most destructive arrows in reaching a mountaintop of feeling. In O. V. Wright’s case, he found comfort in drugs to ease the pain, and he paid the cost by serving time in prison and later with his deteriorating health. In continuing to sing and take his music wherever he could, though, Wright never stopped seeking a way past the turmoil. But it was a two-edged sword that would not go away. Guitarist Johnny Rawls, who spent years leading Wright’s band and released the album Remembering O. V. in October, tried to explain the singer’s plight this way: “O. V. had a huge heart and sang like he was a mountain, but he had demons that would not leave him be.” Those demons might have ended O. V. Wright’s time here when he was only forty-one years old, but his music never ends. Just like life and love, his songs are always beginning, promising to take us to a place well past our earthly reality—promising to take us directly into the spirit world. There they will live forever.

Like this story? Subscribe to the Oxford American.