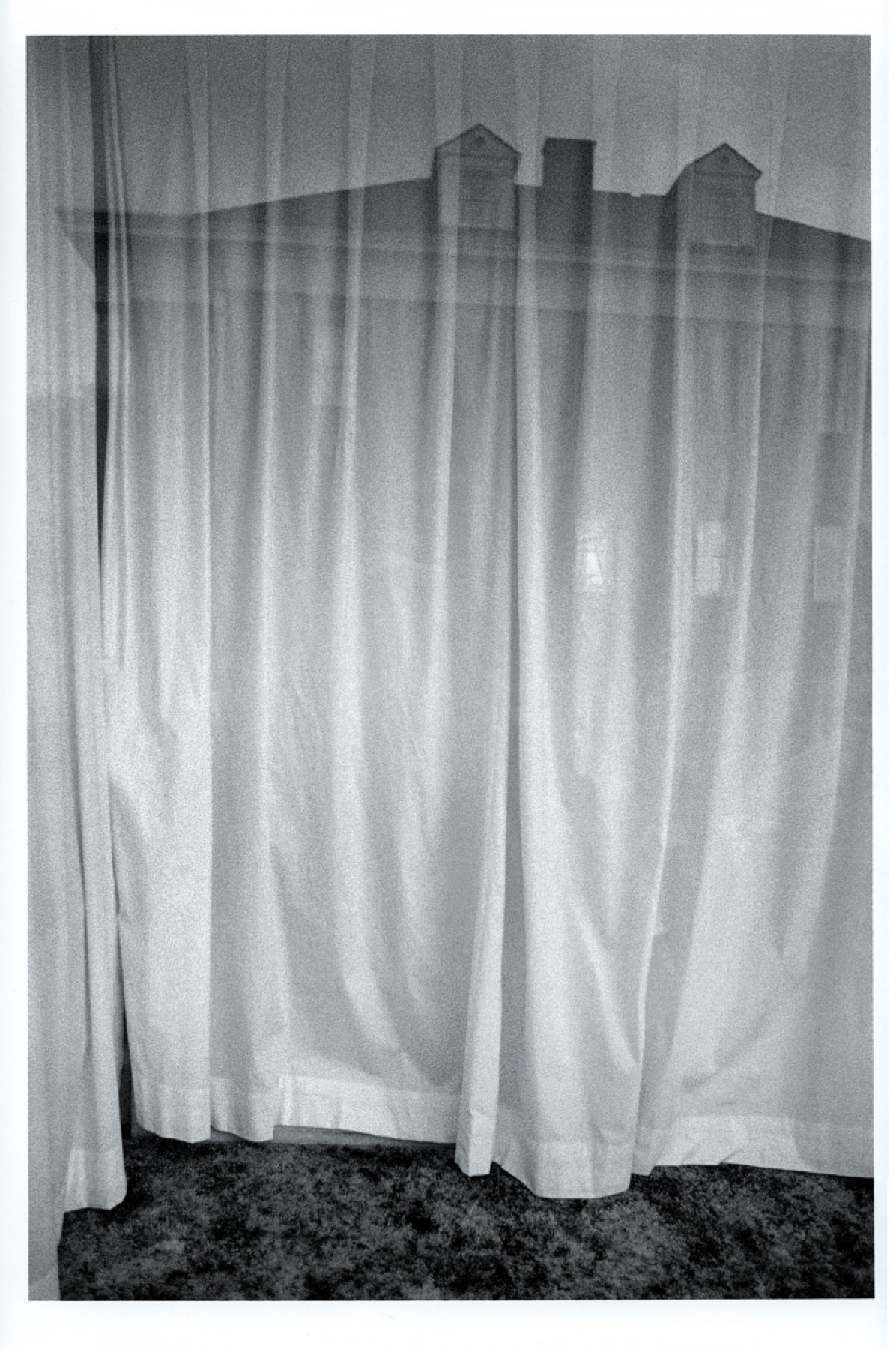

“White Curtain,” by Gary Cawood

My Civil War

By John T. Edge

My friend Dan Philips, a wine importer, likes to drag me into discussions of the Civil War. Though he lives in California, Dan has roots in the South, eats and drinks his way through the region often, and reads voraciously. Dan is smart. And he asks great questions. But I rarely take the bait. The reasons are complicated.

As a boy, the Civil War was too much with me. I grew up in the home of Alfred Iverson Jr., a Confederate brigadier general. On summer afternoons, my friends and I dug for Confederate relics in the side yard of our Federal-style farmhouse, beneath the stooped shelter of a magnolia. I shoveled into the red clay, sure that I would find a rusted saber, a disemboweled pocket watch, a pitted brass button from the great man’s butternut waistcoat. What I found mostly were marbles made of marble, left behind by some other child, from some other time.

A dull bronze historical marker, commissioned by the state of Georgia and erected alongside our gravel driveway in the mid-state hamlet of Clinton, told the story of Iverson’s Civil War exploits. According to the text I memorized when I was seven, he fought for the Union in the Mexican and Mormon campaigns, served the Confederacy with valor at Gettysburg, was wounded during the Seven Days Battles, and, in a brilliant feat of deception at the Battle of Sunshine Church, tricked Union General Stoneman into believing he was surrounded, capturing the officer and more than 500 of his men.

Only recently have I learned that the Iverson narrative was, like many of the history lessons Southern schoolkids like me learned in the 1960s and ’70s, a Redemption-era whitewash of a far uglier reality.

Iverson claimed early career victories. Another success came late. In between, it was mostly briars and bullets and ignominy. At the battle of South Mountain, Federal troops forced his brigade to retreat. At Antietam, his troops turned tail and ran. At Chancellorsville, Iverson took a spent minié ball in the groin. He hit bottom at Gettysburg in July of 1863. On the first day, Iverson sent his North Carolina brigade to battle without cover from skirmishers. Crossing a field of ripening timothy, they stumbled on opposing troops hidden behind a stone wall. The Federals rose and fired so quick and heavy that at least one of Iverson’s soldiers took five shots through the head before he hit the turf.

Rather than rally to their defense, Iverson took shelter in the rear, shouting down his men, calling them cowards for daring to surrender. Without white flags to wave, they hoisted boots and hats on their bayonets to signal defeat. Less than 400 of the approximately 1,300 men in Iverson’s brigade returned from battle. One of his officers said this was the sole battlefield moment when he saw blood run in rivulets. By some reports, Iverson performed poorly because he was too drunk to lead. Others laid comparable blame at the feet of his troops, who were said to have drunk a staggering quantity of tin-canned mint juleps before going into battle. Others still claimed that Iverson, a son of privilege and patronage, had a nervous breakdown at Gettysburg. “Unwarned, unled as a brigade, we went to our doom,” recalled a survivor. “Deep and long must the orphan children of North Carolina rue the rashness of that hour.”

In the wake of those losses, subordinate officers refused to follow his orders. A few weeks later, Robert E. Lee dismissed Iverson from his command and banished him from the Army of Northern Virginia. After the war, Iverson, a tinkerer and dreamer, invented a household ice-making machine, which he failed to bring to market. Late in life, he retired to raise oranges in Florida, where he flourished as a gentleman arborist.

Once I learned that Alfred Iverson Jr. was not an honest war hero, I went deeper. Growing up, I understood that his father, Alfred Iverson Sr., a U.S. senator from Georgia, was a noble statesman. Just last year, I read a New York Times article that told a different story. Iverson the elder was, it seems, a rabid secessionist, a fire-breather in the parlance of the day, who declared from the Senate floor in 1861 that the Union was irredeemable. Nothing could bring the South back from the brink of secession, he argued, short of a guarantee that domestic slavery would be protected. A talented and aggressive debater, Iverson Sr. said of opponents who wished to curtail the advance of slavery, “Let us feed them and fatten them and gorge them out of the public crib, until, like young vultures, they vomit in our faces; let us smother their fanaticism with masses of gold and silver and then, perhaps, they’ll let us keep our niggers.”

For those who deny that the Civil War was fought over slavery, his words serve as a powerful reminder of what was really at stake. “You may whip us, but we will not stay whipped,” Iverson the elder said, sounding a variation on that insidious cry, “The South will rise again,” still shouted today by Southerners who retain little grasp of its meaning. “We will rise again and again to vindicate our right to liberty, and throw off your oppressive and accursed yoke, and never cease the mortal strife until our whole white race is extinguished and our fair land given over to desolation.”

I don’t tell Dan any of this. Instead, I dodge his Civil War gambits and say I’m far more interested in talking about the civil rights movement. And that’s true. I’m flummoxed enough by my own peculiar history, and by lingering sectional animosities, that, in small and quiet moments, I recognize one of the reasons the civil rights movement inspires me: the South, without question, won that war.

But Dan is persistent. And he’s funny. After traveling through Georgia on a wine-selling expedition, he wrote me, “Atlanta must have been a terrible place to defend. All hills and trees and open from all sides, and Coke not yet available in bottles.” Plus he asks out-of-left-field questions that fuse our shared interests in history and food.

“When I was at Chickamauga, I was struck not just by the number of monuments all over the battlefield but by how many were influenced by reconciliation,” Dan e-mailed after a run through Tennessee. “I had this strange image when I was at the edge of the field, within sight of Rosecrans’ headquarters, where Longfellow and the Confederates pierced the Union line.”

He went on, “Standing there, I pictured a big dining table in the middle of one of the fields, set with a big reconciling meal. Does it trivialize history to suggest that food can play some role in history? Do you think a meal like that would be disrespectful to the soldiers who died there or would it honor their memory?”

If you write about food, you face variations on Dan’s question. So do those of us who cook food. And those of us who make meaning out of experiences where food is shared, like the sort of memorializing dinners Dan imagined, in which previously warring factions might gather at long, unbroken, well-laid tables to eat and drink and reconcile.

Food culture reflects history. Like a mirror held up so that we may better see ourselves. Food also affects history. We make decisions about food that drive change and change lives. Columbus set sail for the East in search of spices, but landed instead in the Caribbean. Napoleon recognized that an army travels on its stomach.

Some academics, highlighting home-front food riots, now argue that food scarcity affected the demise of the Confederacy. Anecdotal evidence is strong. In December of 1862, twenty women from Greenville, Alabama, who wanted salt to preserve haunches of hog meat to feed their families through the winter, marched on the train depot, shouting “Salt or blood!” In April of 1863, a mob of women protesters marched on the storehouses of Richmond, capitol of the Confederacy, chanting, “Bread! Bread! Our children are starving while the rich roll in wealth.” Though most were fending for their families, press of the day characterized the women as “prostitutes, professional thieves, Irish and Yankee hags, gallow-birds from all lands but our own.”

By the time Vicksburg, Mississippi, surrendered to Union forces later that same year, scavengers in the local markets were selling dressed rats and flanks of mule meat to starving women and children. When the rats were properly fried, it seems, they tasted like squirrel, which in those desperate times passed for a compliment. The Daily Citizen reported that, although the streets of Vicksburg were suspiciously clear of cats and dogs, editors could not confirm any experiments with canine dishes.

Soldiers fared little better. Confederate troops sometimes failed in battle for lack of sustenance. In April of 1863, Robert E. Lee reported troop rations of one-quarter pound of bacon, eighteen ounces of flour, and ten pounds of rice every three days, with peas and dried fruits on occasion. When Lee wrote to the C.S.A. secretary of war that same year about desertions, he said the main causes were “the insufficiency of food, and non-payment of the troops. There is suffering for want of food.”

When I was growing up in Clinton, history of this sort did not serve as mere backdrop. My mother, Mary Beverly Evans Edge, was a proud member of the Daughters of the American Revolution. And she was a frustrated member of the Old Clinton Historical Society, which she and my father helped found, and which, after a series of internecine tiffs, she took to calling the Old Clinton Hysterical Society.

My mother lived history. Instead of ruining the period aura of our 1814 vintage cottage by ringing our family Christmas tree with strings of electric lights, she decorated our star-topped cedars with garlands of holly and white candles backed by tin reflectors. She was a student of recent history, too. When our Little League all-star team won a regional playoff in 1972, and celebrated at Red Lobster over popcorn shrimp and T-bones, she gave my teammates half-dollar coins embossed with John F. Kennedy’s likeness and delivered a speech that challenged, “Ask not what Little League baseball can do for you, but what you can do for Little League baseball.”

Historical markers were one of my mother’s pet projects. The state-installed Iverson birth placard out front wasn’t enough. When I was twelve, she installed a second Civil War marker halfway up our gravel driveway. A decommissioned sign that she somehow pulled from a privet-tangled ditch, it told the story of the Battle of Sunshine Church, Iverson’s late career victory. The way I heard the story as a boy, Iverson duped Stoneman and captured the highest-ranking Union officer to surrender during the Civil War. The way I now understand the events of that day, a young colonel did the duping and negotiated Stoneman’s surrender, while Iverson remained behind the line of combat, indisposed.

Through the years, the lies have accrued. In my teens, I learned that my mother, whom I thought to be naturally gregarious, garnered some of her social wherewithal from the wine bottle she kept stowed in the bathroom cabinet. The college fraternity I pledged as a seventeen-year-old only child, in search of honest brotherhood, harbored a sawed-off little man with a Hitler crush who, when drunk, once tried to lure a group of equally drunk Jewish coeds into the upstairs shower. But few lies have rattled me like the Iverson lie. He wasn’t a family member. But as a child trying on various identities, from barefoot country boy to prep school aesthete, his provenance appealed. When I told stories of my place and my youth, I always led with Iverson. Then, a couple months after Dan wrote with his question, a book entitled The Paternal Suit arrived, unbidden, in the mail.

A stunningly catholic catalogue of artworks and effects, conceived and created by Iverson descendant F. Scott Hess, it told the same story I was beginning to unspool. Flipping the pages—glimpsing a poster for a “lost” 1942 movie about Iverson Jr. called “The Stoneman Raid,” reading poetry he was said to have written in his Civil War journal, ogling a haunted and hollow death mask said to be made for Iverson Sr. and rescued from a ruined Macon, Georgia, building—confirmed that my tethers to our collective Civil War lies were somehow worth exploring.

I was born in the midst of the four-year-long Civil War centennial. My son, Jess, became a teenager as our nation marked the fiftieth anniversary of Freedom Summer, when activists canvassed the South to register black voters and educate black children. Jess and I talk often about our region, about its tragic history and bright future. I tell Jess that my fight was not the Civil War, but the civil rights movement.

It’s easy to talk about that struggle, about how the good guys won, freeing blacks and whites alike from a social and cultural chokehold. Discussing the Civil War is tougher, more entangling, more confounding. But we talk about it, and I trust Jess understands that you can love a place deeply and still be critical of it. To truly love a place, I tell him, you have to be critical of it.

Back when Jess was nine, we took a tour of the Civil War battlefield at Vicksburg. On a searing summer day, we tramped from monument to monument, gamboling over rammed-earth balustrades, weaving down lawns that could double for country club fairways, crossing sweeps of land that, back in 1863, when locals were eating fried rats that tasted something like fried squirrels, had been strewn with gut-shot Confederates and bayonetted Yanks.

Jess and I didn’t talk much. Instead, we sweated and stared at the white marble horses and the soaring obelisks. As we approached the interpretive center, a park ranger looked up to ask if we had questions. I moved forward. Jess lingered. When I was out of earshot, he asked the ranger something. As he listened, Jess nodded intently. A few minutes later, he met me at the gift shop register with one of those stumpy kepi caps that soldiers wore during the Civil War.

I knew the form. When I was a boy my father bought me one at the Cyclorama, the Grant Park art installation that depicted the 1864 Battle of Atlanta. But there was a difference. The hat my father bought me was butternut grey. As a twenty-first century Southerner, who knows that the South fought the Civil War to preserve slavery, Jess made the only purchase he could. He bought himself a blue bill.

I never thought I would write about the Civil War. That was my past. Not my present. My adult self learned all I needed to know about battlefield memorialization and reenactment in Tony Horowitz’s Confederates in the Attic. After reading Charles Reagan Wilson’s Baptized in Blood, I knew the Lost Cause cold. Thanks to Shelby Foote’s narration of Ken Burns’s epically long television miniseries, I had a decent handle on the interior lives of Confederate soldiers and their families. I was done.

But Dan’s question and F. Scott Hess’s book threw me off my axis. This present can’t fully shake that past, they seemed to say. And I can’t sidestep the rubble. The University of Mississippi, where I work, still refers to itself as Ole Miss, a phrase rooted in an antebellum past when slaves took their direction from the Ole Marse and Ole Miss. Some football fans here drape their tailgating tents in Confederate battle flags. On fall Saturdays others hang banners that depict a doddering Colonel Rebel, the school’s defrocked mascot. No matter my ire, I don’t possess the sustained gumption to question the heritage-not-hate rationalizations that make such uncivil behavior somehow tolerable.

Overt racism is no longer the issue. Our divisions today are cloaked. Squabbles over identity and symbols are now more insidious. What Southerners have in common, however, remains. In addition to an arguable shared ear for music, and an abominable habit of too often electing bad leaders, we possess a definite shared palate, honed over four centuries of cooking out of the same larder, if not always eating at the same table.

Food serves our region as a unifying symbol of the biracial culture we have forged. The power is evident. And it has not yet been fully tapped. That, I think, is what Dan meant to suggest, when he posed his questions. And so I dug one more time, asking, could a dinner like the one he imagined serve some greater purpose? And if so, could time spent at a table, piled high with good food and drink, reconcile combatants now or then?

Turns out that soon after the Civil War concluded, Southerners and Northerners alike began to stage reconciliation dinners. And one of the biggest and most resonant gatherings was staged, as Dan might have it, at Crawfish Springs near Chickamauga. On September 20, 1889, a crowd of 14,000-plus, including veterans from both armies, General William Rosecrans, and former Confederate Major General John B. Gordon, then serving as Governor of Georgia, met there under a bright blue sky in a spirit of friendship. After patriotic speeches, veterans of the Army of the Cumberland and the Army of Tennessee visited with comrades, got acquainted with former enemies, and walked the battlefield where 34,000 men were shot, bayonetted, or trampled, and more than 400 died. Military bands played. Children scampered. Widows preened. And J. R. Treadway of Rome, Georgia, pit-cooked 12,000 pounds of hog, cow, goat, and sheep meat. Thirty tables, each 250 feet long, held the food. Following the meal, veterans smoked ceremonial peace pipes, made from wood harvested on nearby Snodgrass Hill and river cane cut from the banks of West Chickamauga Creek.

Caught in the spirit of the day, celebrants hoisted General Rosencrans and Governor Gordon onto the center table, as the crowd sang a rousing chorus of “Dixie.” Six years later, Chickamauga and Chattanooga National Military Park, the nation’s first and largest national military park, opened its grounds to visitors. In a position paper submitted in support of the park, the House Military Affairs committee wrote, “A field as renowned as this for the stubbornness and brilliancy of its fighting . . . has an importance to the nation as an object lesson of what is possible in American fighting, and the national value of the preservation of such lines for historical and professional study must be apparent to all reflecting minds.”

Enjoy this story? Subscribe to the Oxford American.