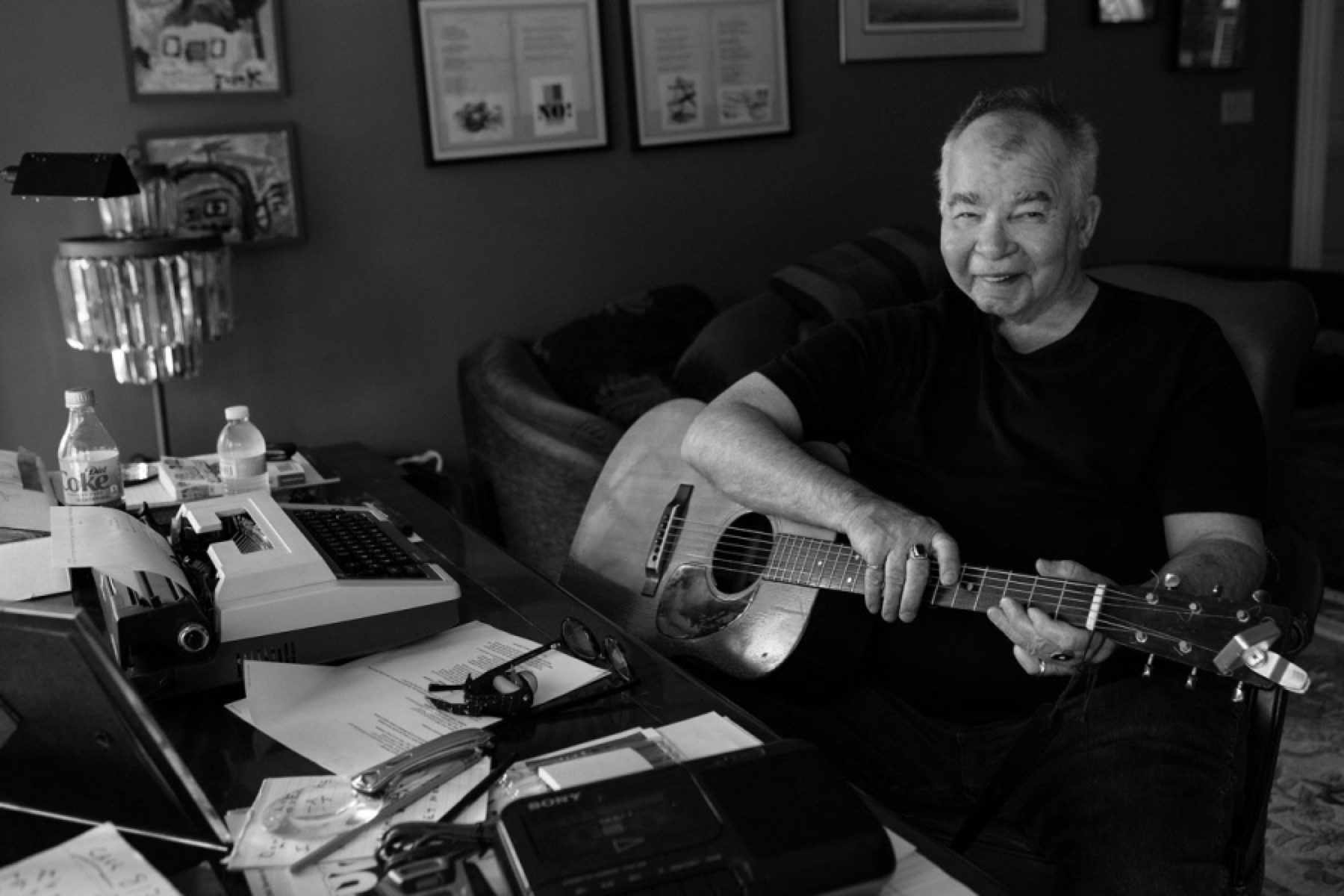

Photograph by David McClister

Living in the Present with John Prine

By Tom Piazza

Old car, new shoes

We are living in the future

I’ll tell you how I know

I read it in the paper

Fifteen years ago.

—“Living in the Future”

I’m leaning against a cherry-red 1977 Coupe de Ville at a CITGO station in Gulfport, Florida, waiting for the car’s owner to emerge from the attached convenience store. It’s got to be at least ninety-five degrees out here, and the heat waves coming off the football-field-sized hood are hypnotic; they bring out the deep luster of the paint job, with its overtones of nail polish, lipstick, and Mad Dog 20/20.

It takes a while, but John Prine finally appears, wearing a big smile and carrying two gallon jugs of water. “Just in case!” he says. “That’s a long bridge coming up.” We are headed for Sarasota, and between it and us stretches a very long causeway, the kind where they tell you to check your gas level before you start across. The car was only just delivered to him two days ago, and aside from a turn or two around the block, this is its first serious drive.

“Isn’t there coolant in the radiator?”

“I don’t know,” he says. “We’ll find out. When it starts smoking we’ll pull over and get a beer!”

Prine radiates a sense of well-being, along with a sort of amused nonchalance toward potential disaster. This is a good thing, because the Coupe, as it turns out, has no passenger-side safety belt. Or rather it has the shoulder belt, but the thing on the seat into which it is supposed to latch is missing. I noticed this awhile back, and it worried me for a few minutes. But then I thought, If you’re going to buy the farm it might as well be in a ’77 Coupe de Ville with John Prine.

He gets in behind the wheel; I climb back into the marshmallow-white leather interior next to him, and as the engine starts with a Wagnerian roar, a middle-aged guy walking in front of us—startled—gives us a grin and a thumbs-up. The proud owner waves back, and the guy keeps looking at the car and smiling as he walks past.

“I like giving people a smile when they see this car,” Prine says, happy as a man can be. “This car brings back dreams.”

“So what is it you want to do?”

Fiona Prine, John’s wife and a warm, gracious, vigilant presence who manages her husband’s affairs, asked me that question three weeks ago, over tea and scones in their new Nashville home, a grand, white-columned manse in an upscale neighborhood south of downtown. They were about to begin touring in support of Prine’s just-released record The Tree of Forgiveness, his first batch of original songs in thirteen years, full of tenderness and rue, longing and mordant high spirits. The tour was going to kick off at New York City’s Radio City Music Hall, no less, with Sturgill Simpson opening. Prine was sweet, funny, a bit reserved, self-effacing as he confessed to being a little nervous about the upcoming tour, and very present. He seemed exactly the person you would expect him to be from his songs. We talked about music, and family, and, finally, after my third cup of tea and my second scone, Fiona fixed me with a friendly but no-nonsense gaze and asked the aforementioned question.

I had been asking myself that same question. Although I knew Prine’s records, especially the earlier ones, I had never seen him perform in person until the fall of 2016, at New Orleans’s Saenger Theatre. The moment that will be indelible, for me, was when his band left him by himself to sing “Mexican Home,” his song about the death of his father. He stood there alone on that big, dark stage, at the front of the cavernous theater, as the entire audience held its breath. As he sang I realized that tears were rolling down my cheeks. What is this all about?, I thought. Something in the human truth of that moment had backed me up against a wall. Right then was when I knew I wanted to write something about him.

It had been a long time—twenty-two years—since I had written a profile of a performer, the legendary bluegrass singer Jimmy Martin, for this magazine. I was forty-one when I wrote that; I’m going to be sixty-three this year. I have never liked sticking a microphone in people’s faces and asking them questions, and anyway I was busy with other things—I had written seven books, wrote for three seasons of the HBO series Treme, and, like many other New Orleans residents, had lived through Hurricane Katrina and rebuilt a life in its aftermath. But somewhere in there while I wasn’t looking I must have crossed a line. People only a few years older than I am have started disappearing with increased and unsettling frequency. Mortality is suddenly the wallpaper in the room.

Prine’s health issues of the past couple of decades are no secret—first the 1997 operation for throat cancer that took away a large part of his neck and left his head in a permanent tilt, then his 2013 operation for lung cancer. They are written all over the seventy-one-year-old face that stares out from the cover of The Tree of Forgiveness, as if challenging you to look straight at the truth. The songs swing between the poles of an almost unbearably bittersweet autumnal melancholy, especially on “Summer’s End” (“Summer’s end came faster than we wanted . . .”), and the exhilarated gallows humor of the final track, “When I Get to Heaven,” a mixture of spoken monologue about Prine’s plans for the afterlife (including forming a rock & roll band and opening a nightclub) and a giddy sung refrain enumerating the pleasures he’ll allow himself when he arrives. It’s a kind of preemptive jazz funeral complete with a ragtag chorus, hand clapping, even a kazoo in there somewhere. It was no stretch to hear it as his goodbye to this life.

And yet, in February 2018, just before the record was officially released, Prine came back to New Orleans and damn near burned down the Orpheum Theater. He did a two-hour show without a break; it climaxed with Prine going into full rockabilly mode while the band riffed on “Lake Marie,” knocking his knees together and finally taking the guitar off and setting it on the stage boards in front of him, doing some unnamable ritual dance around it and then strutting offstage slowly, in time to the music, grinning and soaking in the screams and hollers from the standing audience. He didn’t look like somebody with one foot in the grave. Not only had he endured in the face of all the looming mortality, he continued to stand up and make defiant beauty in spite of it all.

I stumbled over a bunch of words to this effect—what I was trying to express was still unformed in my mind, and maybe not even sayable in words—as Fiona and John listened closely.

Fiona excused herself to get more tea from the kitchen, and when she left, John said, “That kind of surprised me, that she asked you that.”

“Well, I know it’s what she’s supposed to do,” I said. “But that’s really the best answer I could give. If it’s even an answer. Like with writing a novel—I can’t make a plan from beginning to end and then execute it.”

“Yeah—if you knew how it was going to end why would you write it?”

“Exactly.”

Fiona came back in, asked a few more questions, seemed satisfied, and nodded her approval. I looked at John.

“Sounds good to me,” he said.

Instead of a hanging-out-with-John-Prine-in-Nashville article, which she felt has been done to death, Fiona suggested I visit them at a place they own just outside St. Petersburg, Florida. They have been going there for the better part of twenty years, a waterside enclave full of little shops, ex-hippies, palmettos, hibiscus, and laissez-faire. John loves it, and she thought it would be something different.

As I prepared to head down to see them I realized that I was not just looking forward to the visit, but that I was also, on some level, dreading it. This surprised me, and I didn’t understand it at first. Part of my reason for wanting to do the piece was an instinctive feeling that we might be friends, based only on seeing and hearing him perform, and on the limited time we’d already spent together. But in the past year, several friends whom I’ve known for a couple of decades have died. I’ll never hear their voices again, or eat another meal with them. What Prine was singing about on this new record had gotten tied up with that for me; the songs stuck in my mind and forced me to live with those thoughts. That was also part of why I wanted to write the piece, after all. But I also wondered if it was a mistake to get to know him and then possibly lose another friend. . . . It sounds a little crazy as I write it, but it is true.

I arrived in Florida last night in time for dinner at an Italian restaurant a couple of blocks from the Prines’ house, joining John, Fiona, their son Tommy, and a school friend of Tommy’s. They had just come off the first leg of his tour, having sold out Radio City Music Hall, among other venues, and watched as The Tree of Forgiveness vaulted almost immediately to the top of most of the major record sales charts. If mortality was on Prine’s mind it was sealed up in a lead-lined box. The mood was celebratory to say the least, two hours of stories and jokes over an avalanche of seafood and pasta. With his head tilted down from his long-ago neck surgery, Prine is forced to look a little sideways at his listener when he talks, and that look, along with his natural wit, lends almost everything he says an ironic overtone. At one point he mentioned that some people have been telling him that he should write a memoir, but he wasn’t having it.

“That’s for when you’re almost dead, isn’t it?” he said. “I’m just getting started. There’s a lot of things I want to do.”

From someone else this might have sounded false. But Prine was still hungry, in all the senses. He proved this, in fact, by consuming a plate of tiramisu that had been ordered for the two of us. I was telling a story about something I can’t remember now, and by the time I was finished the dessert was gone. Naturally I protested vigorously, which provoked mock accusations, mock defenses, and mock affront from all directions.

As we were winding down, Prine mentioned that he had taken delivery of a 1977 Coupe de Ville the day before; he had bought it on eBay for just over ten thousand dollars—he had bargained the seller down from thirteen-five—and had it transported down from outside Philadelphia. He has always had a thing for old cars, and he was obviously thrilled about this one. “We oughta take it for a ride,” he said. “We’ll go as far as we can get before the engine burns up!”

I felt a surge of relief. Any dread about collaborating on a sober stock-taking, or having a philosophical dialogue about mortality, evaporated right then. Just a goddamn road trip—present tense, in the moment, see where it leads. Open the windows and let mortality blow away.

The wind is whipping in the open windows, and we are cruising down a four-lane highway, heading toward I-275. The Florida sun feels great on my right arm, the hot breeze too, as we pass little hole-in-the-wall joints, more gas stations, wild-looking foliage in between the pawn shops and liquor stores. The exit ramp comes up, and we take it and enter the stream of the southbound interstate.

“I used to have a ’51 Ford. Green, gorgeous,” Prine says. “This is back when I was still living in Chicago. I had been down in Nashville for a few days, and I was heading home on Sunday morning. I had bought one of those CB radios in a truck stop, with the rig on top that you could see. So I’m on the interstate, and there’s nobody else on it. I’m flying, doing about a hundred and ten, and I pass a state trooper parked on the side. He doesn’t even start up his engine; he gets on the CB and he goes, ‘Why don’t you slow that big, bad green thing down? It’s too pretty to stop.’”

He laughs a rumbling laugh that sounds like rocks sliding around in a bowl of eggnog. So far, the vibe in this car is not unlike the easy groove that emanates from the stage when he is performing. It’s as comfortable as hanging out with an old friend. And there’s a boyish streak of kidding that I’m feeling right at home with.

We approach a tollbooth, and he says, “Let’s see if they ask about the car. Maybe they’ll say, ‘Hey just go ahead. The car’s too pretty to charge you.’” He hands the attendant a five, and we wait while she counts out the change and hands it back, poker-faced. John thanks her, and we drive off.

“Not one word,” he says.

“Nothing,” I say.

“Nothing.”

“You’d think we were driving a Volkswagen,” I say.

“She’s too young,” he says. “Oh man, this is nice. This car is loving this ride. If you’ve never been to Sarasota you’re going to like it.”

There’s a cop maybe twenty yards up ahead of us, and I mention this to him. I have been riding with the missing seatbelt’s shoulder strap pulled across my chest. “What are the seatbelt laws here?” I say. “I’m trying to look like I’m wearing this thing . . .”

“We can just get you a t-shirt that has a seatbelt printed on it,” he says. “Wait—where’d you see a cop?”

“In front of us. Isn’t that a cop?”

“I can’t see that far,” he says.

I look at him to see if he’s joking.

“When I’m driving in Colorado, every car with a ski rack on the roof looks like a cop. That’s okay, I’m doing the speed limit. I just don’t have a legal plate on the car.” He explains that he took the plates off his RV and placed them on the Caddy temporarily.

Now I can’t help laughing; it’s starting to feel like a vaudeville routine—no seatbelt, no coolant in the radiator, illegal plates, a half-blind driver…

“Only fifteen miles to Sarasota,” he reads from a sign, as if to prove that he isn’t completely blind. “You’re gonna love this bridge they got up ahead. They built it so the big ships can go under it. It’s so steep going up it looks like you’re gonna drop off the other side.”

This apparently reminds him to reach back and fasten his own safety belt, which, unlike mine, does have a latch on the seat. I remind him that there’s no latch on my side.

“It’s down over here,” he says, pointing at the seat next to me.

“No, it’s not there.”

“Sometimes it’s underneath,” he says, “right under here . . .” He looks down, and the car veers sharply to the right.

“Keep your eyes on the road!” I shout. The car veers back into the lane.

“Here comes the bridge, Tom! They haven’t finished the other half yet! I forgot to tell ya.” From this angle it does look as if the bridge rising steeply in front of us ends abruptly in mid-air.

“What?” I say. “We’ll go off the end!”

“Yeah! This is it! Thelma and Louise!”

We’re both laughing now, and I hope he can see the road, because I can’t. We make it safely over the top of the hump and down the other side and roll alongside gorgeous, sun-spangled bay water off to our right. I ask him how he found this place.

“It was mostly a matter of me coming down to play in the late seventies, different places,” he says. “Later on, this one guy was trying to make a venue out of that little casino down by the water, and me and Fiona came over to have lunch and just fell in love with it.”

We drive along, talking about different parts of Florida that we know, about Nashville and New Orleans, just yacking, until he leans forward, squints out the window, and says, “We’re already to Sarasota!” He laughs and points to a sign. “We talked our way here!”

We follow the signs to St. Armands Circle, a kind of compact shoppers’ Disneyland with a fountain in the middle and lots of high-end shops, carefully landscaped, cafés and tables under awnings on the sidewalks. Lots of middle-age and retirement-age folks wearing formidable tans and Bermuda shorts.

“This car deserves a parking space right on the circle,” John says, scanning for a likely spot. He points out a shoe store that he wants to stop into. We make a full circuit of St. Armands and, miraculously, a space large enough for the Coupe de Ville has opened right in front of the Columbia Restaurant, a classic Cuban place, a satellite of the original in Tampa.

“I’m used to not finding parking here this easily,” John says, in wonder, as he maneuvers us into the space, with lunchtime diners watching us. “It must be our karma.”

“I hope we aren’t blowing our whole karma just on this,” I say. “I mean it’s a worthwhile thing, but . . .”

“Very worthwhile! A ’77 Cadillac? Are you kidding?”

The last time I wrote a profile of a musician—that Jimmy Martin piece, twenty-two years ago—I ended up backstage at the Grand Ole Opry. Crowded hallways with people hollering and pushing their way through, musicians in jeweled suits warming up with fiddles and guitars, people telling jokes and other people squeezing past on their way to the stage. Jimmy had gotten drunk at his house, and I had to drive us to Opryland in his midnight-blue Lincoln stretch limo, which kept stalling out; when we got there he tried to pick a fight with Ricky Skaggs and almost managed to punch out Bill Anderson. So far the worst thing that’s happened on this trip is that Prine hogged all the tiramisu last night. And now we are going to a shoe store. A shoe store, I think—this is what twenty-two years can do for you.

We walk into the store, and John heads for a display where leather Top-Siders are lined up. I look around the shop. I’ve been having trouble with my own feet, actually. The salesperson greets me respectfully and calls me “sir.” As long as John’s trying out shoes I figure there’s nothing to lose by looking at some myself. There’s a slightly weird-looking pair, a dove-gray hybrid of sneaker, boat shoe, and walking shoe. I ask the clerk for a pair in 10 1/2; he brings them and they feel pretty good, incredibly lightweight, although there is a lot of room up by my toes, and the tops of the shoes have a kind of weird pucker; they look like space shoes. I ask the clerk if I can see a pair of tens.

While I’ve been doing this, John has settled on a pair of boat shoes featuring extremely shiny brass eyelets. They are some seriously bright eyelets.

“Jeez,” I say. “You’ll have to wear sunglasses to cut down on the glare.”

“They feel great,” he says, walking back and forth.

“It’s nice they throw in the shoes when you buy the eyelets.”

“I can black them out with a magic marker.”

We both buy the shoes we’ve been looking at. We walk outside into the heat and stand in front of the store, holding our shopping bags. I’m trying not to imagine what we must look like. We put on our sunglasses. “There’s your article, right there,” he says. “Buying shoes with John Prine!”

We walk back around the circle looking for a place where we can talk and get something to eat. I’ve got Kacey Musgraves’s song stuck in my head, about how her idea of heaven is to “burn one with John Prine.” He elicits that feeling in people. There’s no question that fans love him in a special way; they sing along at his concerts, shout out requests that he deflects with funny one-liners. (Audience members: “Fish and Whistle!” “Flag Decal!” “Paradise!” Prine smiles, strums a chord or two and says, “Yeah; I know ’em all!” Then he sings “Grandpa Was a Carpenter.”) He generates a clublike intimacy even in the biggest venues; people feel as if he’s their friend, just as I did. But you don’t get the whimsy and shrewdness and fun of his songs without the other stuff—the long, empty hours in the kitchen listening to the flies buzz (“Angel from Montgomery”), the son lost for no reason in Korea (“Hello In There”), the family’s meager income disappearing into “a hole in Daddy’s arm” (“Sam Stone”). Or Prine’s own father dying on the porch on a stifling afternoon in “Mexican Home,” the song that broke me up when I first saw him onstage in New Orleans.

Bob Dylan once called Prine’s songs “Pure Proustian existentialism—Midwestern mind trips to the Nth degree.” John and I talked about Dylan some last night—we have both spent time around him in different contexts— and it made me think about the different energies they emit in performance. Dylan exerts a magnetic, almost hypnotic, pull on many of his fans—a lot of male fans, especially, envision themselves in Dylan’s place when they listen to him; a lot of them seem to live vicariously through him. Prine is different. You don’t want to be him, you just want to hang out with him.

It is three o’clock, well after the noon rush, and we stop into a nice seafood place for a snack. We had a large, late breakfast, and neither of us is particularly hungry. We get settled, look at menus, order soup, and I ask John when he first met Bob Dylan.

“I was in New York,” he says, “a couple of months before my first record came out. It was the second time I went there. The first time was three months earlier, when I got the contract from Atlantic. I made the record, and now it’s maybe late August of 1971. My record isn’t coming out till October. I’m in New York with Steve Goodman, and Kristofferson is in town too. Kris calls and says, ‘Why don’t you guys come on over—I’m hanging out at Carly Simon’s apartment. I got a surprise for ya.’ So we go to Carly’s apartment, and after a while there’s a knock at the door, and it’s Bob Dylan. I signed a record contract three months earlier, it’s the second time I’ve been in New York City, and who do I meet?

“He comes in, sits down, we all talk, and within the hour Carly passed the guitar around and we started singing. Bob had just wrote ‘George Jackson,’ like the week before. He sings that, and Goodman, who’s a smart aleck, leans in and goes, ‘That’s great Bob, but it ain’t no ‘Masters of War.’”

“How did Bob react when he said that?”

“Totally cool. I wouldn’t have gotten away with it! So then I sing a song.”

“What did you sing?”

“I sang ‘Far From Me.’ And around the second chorus, Bob starts singing along. I almost fell off my seat. My record’s not out for another two months. Turns out Jerry Wexler at Atlantic had sent him an advance copy. Bob knew the words already! The entire time that first meeting, I felt like I was in a dream. Except for Kris I had never met anybody whose records I owned.”

Our soup arrives, and John keeps talking.

“We had another buddy with us,” he says. “Eddie Olsen, who was a Chicago folksinger.

He was sitting there with his mouth hangin’ open. He didn’t believe he had run into Bob Dylan. So Eddie pipes up and goes—to his new friend Bob—he goes, ‘Hey Bob, there’s some people back in Chicago that think John Prine sounds like you. What do you think?’ Bob looks at him, then he looks at me and says, ‘The first time I heard your record I thought you’d swallowed a Jew’s harp.’” John cracks up laughing at this.

“And then throughout the years, little by little, I ran into all of his relatives, totally by accident. I went to see Bob at a show in Chicago, and I ended up sitting next to his mom. I got introduced to her and she said, ‘Oh, we’ve heard a lot about you, John Prine.’ I met his brother David—his brother ran the theater in Minneapolis. Bob’s wife, Sara, before they got divorced, told me she used to play my records at home all the time. And I’m thinking, ‘That musta drove Bob nuts!’ His son Jakob said when they were kids they would sing ‘Fish and Whistle.’”

He eats some soup, starts laughing again.

“‘Thought I’d swallowed a Jew’s harp . . .’ My voice can sound unusual, but . . . I always kind of wish, if I’d had my druthers, I’d-a rather sang for about two years in the Chicago clubs and really got my footing, ’cause it had hit me like a ton of bricks—having a record out, touring across the country, and meeting your heroes. I wish I woulda been a little more prepared for it. But I don’t know how prepared you can get.”

He asks me when I first met Dylan, and I tell him the story. In 1991 I left New York City, where I’d lived for fourteen years, to attend the Iowa Writers’ Workshop. I’d been having some success writing about music, but I really wanted to concentrate on writing fiction, and Iowa gave me a fellowship. Before I left New York there had been discussions with Dylan’s management about my doing an article on him, but nothing had come of it by the time I left town for Iowa City. I was there for two months when I heard that Dylan was coming to Ames, a couple of hours away. Two nights before the concert there was an ice storm that paralyzed that part of the state, but they cleared the interstate and I packed the car with blankets and food in case I got stuck someplace. I drove to Ames, and the gods took pity on me, because I was invited backstage and spent about twenty minutes with Bob before the show.

“It was just really comfortable, completely relaxed and fun,” I say. “The charisma meter was set to zero. He had a copy of Poe’s collected tales and poems on a little table. He asked me about the workshop; he said, ‘Does it help?’ He asked me if I thought The Great Gatsby was a great book, asked if I had read the biography of Buddy Rich that had just come out, written by Mel Tormé, asked where I was raised. He was so gracious—courtly, almost—and I liked him immediately. But you were aware that you weren’t talking to somebody who was exactly like other people. Hard to put your finger on it, but there was something that was just different. But I also knew that everybody acts with him as if he’s Bob Dylan. That’s the worst thing you could do.”

The waiter comes by and I order a decaf cappuccino. John orders the Granny Smith apple tart with vanilla ice cream. “And an extra scoop of vanilla,” he says, “and two spoons or forks, or whatever ya got, and we’ll see who tells the longest story!” This is a reference to last night’s tiramisu fiasco.

The waiter leaves; John is still thinking about Dylan.

“I very rarely go to see somebody backstage before a show,” John says. “’Cause I know how I feel. No matter how important a person is, I might be having the jitters, or this or that. I think the only time I went and saw Bob backstage was in 1975. I was in New York City, and I had just had a meeting with Ahmet Ertegun at Atlantic Records and told him I wanted to leave the label. I’d done four albums in three years. My contract called for ten records in a five-year period—of original material! I was supposed to hand in two LPs of John Prine songs every year, and they had half my publishing!

“It was a Friday afternoon, and me and my manager, Al Bunetta, were at the appointment with Ahmet. I told Ahmet, ‘You’re runnin’ around the country with Led Zeppelin, and the Rolling Stones, which I would be doing if I was you, too. But I need somebody to at least argue with me. Tell me ‘Why don’t you do this?’ Then I could go, ‘No, why don’t I do that.’ It’s four o’clock on a Friday afternoon, at Rockefeller Plaza—they had just moved their offices over there—and I went to the window—I must have been high—and said, ‘Look.’ He came over to me, and I said, ‘Look at all those people. You used to make records for them. I don’t think you do anymore. I would like to go. Nowhere in particular, but somewhere else.’

“He wasn’t prepared for it, you know? He didn’t know quite what to do. He said, ‘Well, if that’s the way you feel, we’ll figure out how you can get out.’ Then he says, ‘Is there anything else I can do for you?’ I said, ‘Yeah. Give me your limousine; I want to go see Bob Dylan in Hartford.’ So he gave me his limousine and a driver! Me and Al are in the back of this limo, with cigars, driving up to Hartford! Al calls somebody and tells them we’d like to come back and see Bob. No problem. Bob was in a great mood, ’cause the Rolling Thunder thing was going.”

This was the road show Dylan assembled to tour the country, with Joan Baez and various guest stars who would come and go, like Ramblin’ Jack Elliott and Joni Mitchell. I always wished I’d been able to see one of those concerts.

“There’s a great picture of Bob and Springsteen and me, backstage,” John says. “Springsteen had just put out Born to Run, and I’m standing there laughing at the two of them, ’cause they’re acting like outlaws, like they’re gunfighters. That was one of the best shows I’ve ever seen. He must have been like that when he was on fire in the mid-sixties, I mean real on. He was out there putting everything into it. Whether it was a solo song, or with the band. It was so loose, he loved it—it was just noise, rock & roll noise.”

The waiter brings the coffee and dessert, the apple tart accompanied by two small mountains of melting vanilla ice cream.

“We’ll hit the road after this,” John says as we dig in. “It’s quarter of five; we won’t get back till almost seven, depending on what traffic we hit.”

“I’ve actually been trying to lose some weight.” I say. “You can tell how hard I’ve been trying.”

“I didn’t know you were trying to lose weight,” he says, and laughs. “I wouldn’t have ordered all these desserts.”

“No, it’s good. I’ve been looking for somebody to blame.”

“Go ahead,” he says. “Bring it. See right now, I lose weight when my mind kicks in. Like ever since I had the record out and I’m on the road? I’m burning calories in my mind all the time. I don’t know how it works, but I lose weight while my mind’s spinning like crazy.”

“But you’re also doing all that physical activity onstage, right?”

“I guess, but I lost twenty pounds, and it’s all because my metabolism is sped up.”

“That’s a lot of weight,” I say. “I should start thinking more.”

Eventually we head out. I try to fight off a twinge of melancholy as we climb into the Caddy, leave St. Armands, and head north. I don’t want the afternoon to end. The sun is lower in the sky now; the light is deeper and richer, but it’s obvious where it’s headed. Not dark yet, but getting there, to paraphrase Dylan.

“I told you I know how to waste a day,” he says. “At least we got something done. It’s the perfect way to do it.”

We pass a big colony of white birds on a stretch of grass; John points them out, and we both struggle to remember what they are called. Finally John says, “Flamingos.”

“They’re not flamingos!” I say. “Flamingos are pink.”

“Well, they don’t have to be.”

I realize that I’m not absolutely sure about this, but I express my doubts and he doubles down. “There’s white flamingos,” he says, defiantly. “The pink ones are tastier.”

We roll along with the Gulf on our left now, past condos and subdivisions, palm trees, small hotels. No clouds in the sky, just the most beautiful Florida day you could picture.

“You know,” I say, “you were joking about writing the article about shopping for shoes. But remember that day when Fiona brought the gavel down?”

“Yeah—‘What are you gonna do, and who are you doin’ it for?’”

I remind him of some of the things I’d said that afternoon, about continuing to produce what one produces even with mortality beating on the door, and I mention a photo of him in the CD booklet for Lost Dogs and Mixed Blessings in which he’s leaning on a fence next to a cemetery. The record was released in 1995; a year later he was diagnosed with cancer the first time.

“Whistling by the graveyard,” he says. “I did that on purpose. I asked the guy—we were down there taking pictures. I said, ‘Get a picture of me walking by here, whistling.’”

“Okay, so as long as we’re sort of talking about it?”

He’s quiet now, for a minute.

“I’m not sure,” he says, “but I think that when I write about the idea of mortality—not just now, but earlier—it might have to do with something in my sense of humor. Mortality is a natural target for it. I’ve written songs where I’ve talked about a guy dies and goes straight to heaven, and this happens or that happens. It’s a target that I’m drawn to, to get my humor through. So like right now, because I’m seventy-one, all of a sudden articles are going, ‘This guy’s writing about mortality,’ whereas before they thought I was just joking. I think that’s part of it. ’Cause it’s not like I haven’t written about it before. It’s just I wasn’t seventy-one before.”

“Do you wonder about it? Speculate about it?”

“I don’t think so. I think it’s just a natural ending to life. It’s the only option. There’s life, and there’s death; there’s not much in between. You fall in love, you’re trapped inside these bodies, the clock goes around, and before you know it—it’s time to go!”

“But you do write an unusually large number of songs where there are scenes set in the afterlife. A lot of stuff with Saint Peter. ‘Flag Decal,’ ‘Please Don’t Bury Me.’ Is that really just a device?”

He mulls this for a moment. “I think I believe in the afterlife,” he says. Then, “Maybe not. Also I think it doesn’t matter, ’cause nobody can check in with me after I’m gone. I do think your soul lives on. But I don’t think, if there is a heaven for your soul—I don’t think one soul would know another. Except out of kindness and graciousness, stuff that’s supposed to be heavenly. You just go somewhere, and you might even come back as something else. But you wouldn’t know it, right? Maybe you just get dry-cleaned and come back as something else! I think most people believe you die and that’s it. They cremate you out of kindness and then throw your ashes in an ashtray and you’re outta here.

“I never felt particularly like I feared death, you know?” he says. “Even when I was first told I had cancer. I never felt like it was gonna consume me. Like I wasn’t gonna be here. It was scary, but I didn’t feel like I wasn’t gonna make it. I never did. I believed in my doctors; it was like, ‘What do you want to do, and what’s my plans after surgery?’”

He’s quiet again, then he says, “Fiona had it tough. She had it tough.”

“How long had you been together at that point?”

“Both babies had just been born. The kids were, like, one, and the other one wasn’t two yet. And all of a sudden I had cancer? Fiona thought the world was caving in.”

Then he says, “Don’t turn around, but there’s a cop behind us.”

I can’t tell if he’s serious. But why would he have interrupted that story for a joke? “You think I should wave to him?”

“No, I don’t think so.” John’s checking out the rearview. “Maybe he’s calling the plate in.”

“He isn’t calling in our plate. We’re fine.”

“I’m doing the speed limit.”

“I think we look pretty clean cut.”

“We look like two retired citizens.”

“Wait a second . . .”

“All right: father and son.”

“You don’t have to go that far. Is he still behind us?”

“Yep.”

“I have no idea,” I say, “what I think about any of that mortality stuff. I really don’t. After my dad died a couple of really weird things happened. In no way would I think there’s somebody up there working levers like the Wizard of Oz. But, on the other hand, for instance, my dad died on August 16th. For about ten years after, maybe a little bit more . . .”

“Wait. What’d you just say?”

“My dad died on August 16th,” I say. “2002.”

“2002.”

“Yeah.”

“That’s the day my dad died,” he said. “In 1971. August 16th.”

“That’s a little weird,” I say.

“I’m sorry; go ahead,” he says. “That was too weird.”

It is actually kind of spooky, especially given that hearing him sing “Mexican Home” was what made me want to write about him in the first place. But I go on with the story. “He died of sepsis after a gall bladder operation. He was in ICU for three days; his heart stopped once, they revived him. So the day he died, right after we gave the do-not-resuscitate order—his heart had stopped a second time—right after that there was a cloudburst, like a thunderstorm that lasted only maybe ten minutes. And then there was this incredible rainbow. Every year after that, for ten years or so, on August 16th, in the afternoon, wherever I was, there would be some kind of thunderstorm or strong rain, and then a rainbow.”

“Wow.”

“Every year, on August 16th. Roughly the same time of day. And listen to this. I was at an artists’ residency in Saratoga Springs— Yaddo, a big old mansion. It was 2004, exactly two years after my dad died. We were all just finishing dinner and there was a gigantic cloudburst. After the rain was finished there was this huge rainbow, really big and close, almost fluorescent. Everybody walked out of the dining room onto the terrace to look at it.”

“That’s crazy.”

“But this is the crazy part. So I’m standing there watching it, thinking, ‘There you are again. You did it again.’ And then I thought, ‘Okay—you want to really impress me? Make it a double rainbow. Come on, let’s see whatcha got.’”

“Let’s see what you got. Bring it on.”

“And the fucking rainbow turned into a double rainbow.” John starts laughing at this, and I say, “I’m not kidding, John!”

“No!” he says. “I know! My mother’s a redbird. Every time I move, within the first week, a redbird comes to the window, looks me in the eye. I’m like, ‘Thanks, Mom.’ She’s just checking on us.”

He stops talking and looks in the rearview mirror with an alarmed look. “Look—now he’s going past us; he’s . . .”

The police car passes us, only it isn’t a police car—it’s a Honda with a ski rack on top.

“Oh fuck,” he says, laughing. “I just lost three years of my life! There’s the rainbow!”

When he has recovered he says, “But August 16th, though—that’s etched in my mind. I had just been visiting, having a beer with him on the porch, and I had to go. I had stuff to do—I was married—and I said, ‘I gotta go home, Dad.’ And he said, ‘Aw, come on; sit and have another beer with your old man.’ About an hour later, my little brother came out and found him slumped over in the chair, on the front porch. He’d been sitting on the front porch looking at the cars going by, drinking his beer and daydreaming.”

“Had he been sick?”

“He’d had a heart condition since he was in his mid-forties. I could tell he didn’t really take care of himself. He didn’t like doctors; if a doctor told him to quit drinking he’d find another doctor. But he wasn’t a drunk. And when he got drunk he wasn’t mean.”

John’s cell—an old-fashioned flip phone— pings, and he asks me to read him the text. It’s from Fiona: See you at 7-ish.

I text her back on my own phone to say that we’ll be there right about seven. A couple of seconds later she texts me back that she is reading one of my books, which I had given her, and is “riveted.” I tell John this.

“Is that what she said? Made your day!”

“Sure did,” I say.

“Well, don’t tell her the ending,” he says. “Kris’s got a beautiful song, about ‘Please don’t tell me how the story ends.’”

Right, I think. We are approaching a rise in the road, a railroad crossing, and we take it a little faster than we should, but we come down smoothly on the other side of the hump.

“I thought we were gonna take flight, there,” John says.

I ask him if he knows Chuck Berry’s song “You Can’t Catch Me,” with the line about the “custom-made Flight De Ville . . .”

“Got it,” John says. “In ‘You Never Can Tell’ he calls a refrigerator a ‘coolerator.’”

We both sing the line, “The coolerator was crammed with TV dinners and ginger ale.”

I see no reason to stop there. “And when Pierre found work . . .”

He joins in, singing, “. . . the little money come in worked out well. C’est la vie say the old folks . . .”

We continue down the road singing, and if that moment could have lasted forever it would have been just fine with me.

We arrive back in the little waterside village around seven, cruising slowly down the main street with the windows open, toward his house and my hotel. A guy in his thirties is about to cross the street; he stops, watching us. As we pass, he hollers, “John Prine!”

John waves at him and says, “Hey!”

As we continue down the block John chuckles and says, “Not that I’m drawing attention in this car or anything.”

He pulls around back of the hotel and says, “We’ll go to eat dinner in an hour or so. Come by the house. I’m gonna lay down for half an hour.”

I tell him I might do the same. As he’s about to start off, the guy we just saw comes running up to us, out of breath. He apologizes for interrupting and asks if it’s okay to take a picture. John says, “Of course.”

I recognize the impulse—the desire to stop time, to fix the moment, prove to yourself in the future that your times coincided. The guy hands me his phone; I take his photo with John, and he thanks us and leaves.

John gives me a thumbs-up and says, “See you in a while.” I watch him drive off and disappear around the corner. Then I go inside to rest up a little and get ready for dinner, happy to put off having to think—for a while, at least—about how the story ends.

Enjoy this story? Subscribe to the Oxford American.