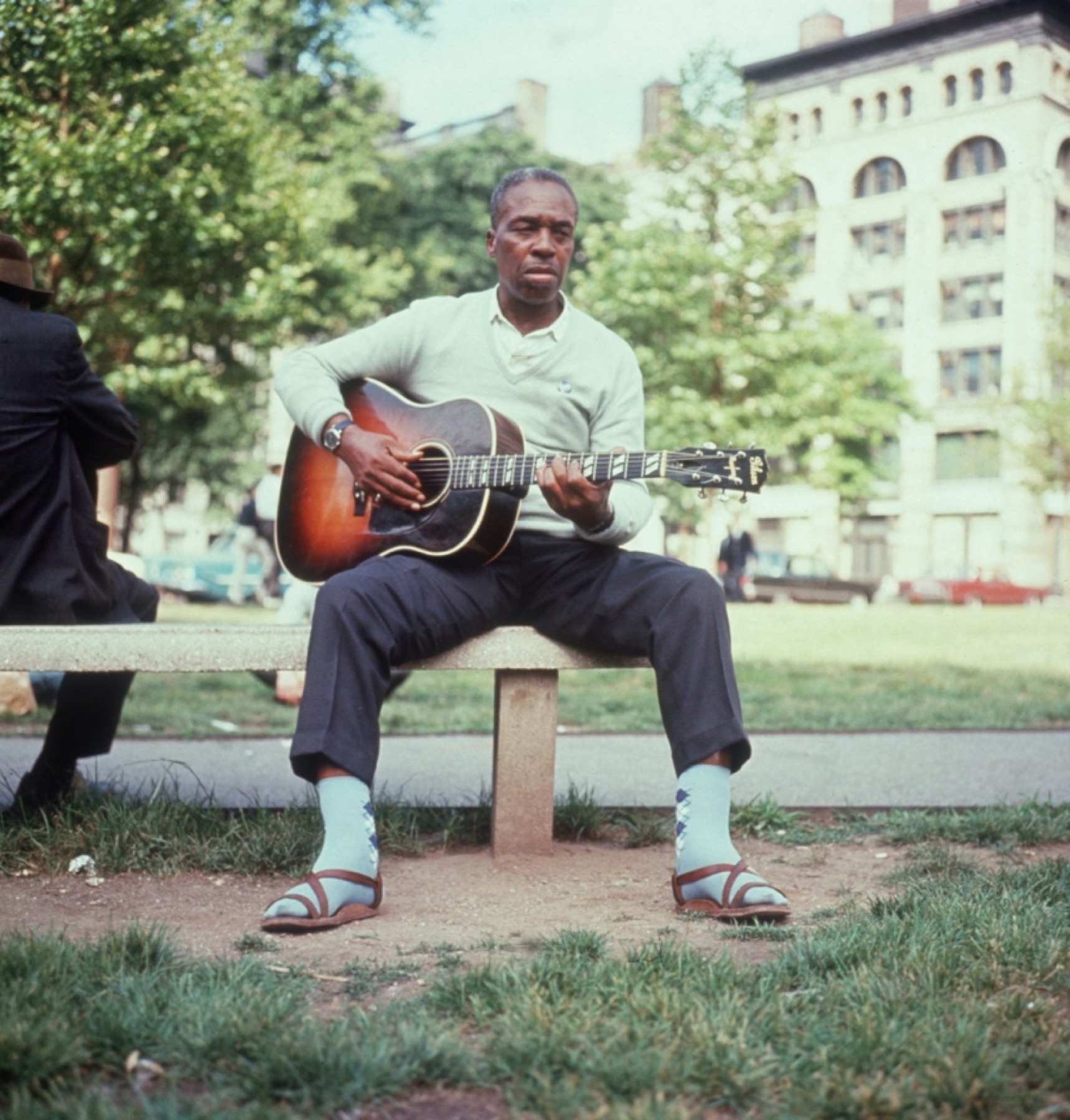

Photo of Skip James (1965) by Bernard Gotfryd/Hulton Archive/Getty Images

Whose Skip James is This?

By Peter Guralnick

Ifirst met Skip James at Dick Waterman’s apartment in Cambridge in the summer of 1965. I sought him out because, quite simply, his music had overwhelmed me: the blues that he had recorded for Paramount Records in 1931 on piano and guitar, four of whose sides had been reissued on collectors’ labels in the early ’60s, had struck me as unfathomably strange, beautiful, and profound. Then in June of 1964 the singer himself was rediscovered in a hospital in Tunica, Mississippi, and when he appeared at the Newport Folk Festival some five or six weeks later, his music was just as haunting, just as profound, his pure falsetto floated out over that festival field with all the ethereal power of the records but with a new and eerie reality. When, a year later, he was booked into Club 47 in Cambridge and I found out that he would be staying with Dick Waterman, who managed Mississippi John Hurt and Son House at the time and would very shortly take over Skip’s booking and management, too, I felt an obligation to seek him out. I’m not sure what exactly emboldened me. I didn’t know Dick, except as one of the blues elite who could hang out backstage at Newport or stride past the waiting lines at Club 47 and walk right in the door. I certainly didn’t know Skip. And at twenty-one, I was temperamentally disinclined to approach anyone outside the realm of my immediate circle of acquaintance. But I felt, not without an ironic recognition of my own foolishness and insignificance—for no other reason but my overwhelming admiration for his work, the scope of his imagination, I simply felt compelled to do it.

I had never formally interviewed anyone before. The closest I had come was when I went to see the English novelist Henry Green two years earlier under similar circumstances, and for much the same reasons. He was a writer I admired so much that I wrote to him when I arrived in England and asked if I could come visit. When he wrote back and agreed to my importunity, I was panic-stricken—but I remained committed to my belief in art. So I summoned up what little courage I possessed, overcame every existential scruple I had about actually declaring myself (I was a fully signed-up member of the mumbling school of self-effacement), and spent an excruciatingly self-conscious, gloriously transcendent afternoon listening to Henry Green expound upon his views of life and art.

That is more or less what I did with Skip. I called up Dick and told him that I wanted to interview Skip for an article in Blues Unlimited, an English fanzine which was the first—and, with Jim and Amy O’Neal’s Living Blues, which didn’t come along until 1970, probably the most adventurous—of all the blues periodicals. Now, I should explain that at the time I had not yet seen Blues Unlimited, which had begun its mimeographed publication two years earlier. I had in fact only recently learned of its existence, through a Nat Hentoff column in The Reporter, and I had been in touch with its two editors, Simon Napier and Mike Leadbitter, by mail for the past six months without ever having received the first issue of my subscription. It came as something of a surprise, then, when Dick expressed skepticism that Blues Unlimited should want to undertake another story on Skip so soon after completing a three-part series. I’m not sure just how I recovered from that, but in the end I found myself sitting in my car on Concord Avenue nervously contemplating my future. I was in fact trying to decide whether or not to take the bulky Norelco tape recorder that was sitting on the front seat beside me out of the car and down the street to Dick’s apartment, and it was a spirited inner debate. My father, who had been the editor of his college newspaper, had urged me to leave the tape recorder at home, a real reporter relied solely on his notes, he said—but that was not my primary consideration. What really disturbed me was a much simpler issue: How could I walk in and introduce myself to someone carrying all this baggage? In the end I left the tape recorder in the car, squared my shoulders, and marched in to meet my fate, to present myself to Skip James, unencumbered if not unafraid.

The man that I met was gracious and reserved, quietly observant but somewhat amused, too, and patient with my foolishness. I knew at the time that the questions I had put together were tiresome both in their obviousness and in their abstraction, but I couldn’t think of any others, and Skip dealt with every one of them in a dignified, almost ceremonious way. He would counter the naive wonderment of a twenty-one-year-old with the concrete experience of a man forty years my senior. Why’d he quit? “I was so disappointed. Wouldn’t you be disappointed, man? I cut twenty-six sides for Paramount in Grafton, Wisconsin. I didn’t get paid but $40. That’s not doing very good. Wouldn’t you be disappointed?” At other times he would brandish a polysyllabic vocabulary at total odds with the stereotype of the “primitive” bluesman but very much in keeping with what I took to be the dark secrets of his music. When I left, it was with the same sense of conflicting excitement and relief that I’ve come to recognize from countless subsequent interviews over the years: the feeling that I had done it, I had escaped without revealing myself as a total fraud, but without having gotten to the heart of the matter either.

I saw Skip James several dozen times over the next few years. His comeback was truncated by illness (he died in 1969) and was not in any case a major marker of success. Generally there would be twenty or thirty people at his performances, sometimes less. Often one felt an obligation to attend, if only out of loyalty. As Dick Waterman observed: “He was a man of intense pride in his ability. He was a genius, and he knew it.” He was also aware, Dick pointed out, that “his good friend Mississippi John Hurt’s music was much more widely accepted, that John played to wider and larger audiences, that John was an artist in demand, that John made more money. That, however, did not under any circumstances alter his appraisal of John’s music. Which was that it was play-party, ball-less, pleasant music, good music for dances and country reels but not to be taken seriously as great blues.”

You could see the effect on his music: it appeared to be hampered not just by the cancer that was eating away at him but by disappointment, and the unquestionable seriousness with which he took himself. The first time I saw him play after Newport, in the fall of ’64, he was booked for a week into a folk club, the Unicorn, in Boston with John Hurt, and they sang just about everything you could imagine, from Jimmie Rodgers yodels (on which they would duet) to Skip’s knocked-out versions of “Lazybones,” “Silent Night,” and “Girl of My Dreams” at the piano. Later on he would grow visibly more constrained, seeming to view his bookings almost as concert recitals, patiently instructing his audience about a way of life and a musical tradition with which they could not possibly be familiar, in a manner that was both disconcertingly and almost touchingly formal. (“As I first said, it’s a privilege and an honor and a courtesy at this time and at this age to be able to confront you with something that may perhaps go down in your hearing and may be in history after I’m gone.”) He never failed to sing his trademark number, “Devil Got My Woman,” the inspiration for Robert Johnson’s “Hellhound on My Trail” (it is a peculiar footnote to history that Skip James, whose Paramount releases were among the most obscure “country blues” sides, should have provided the impetus for two of Robert Johnson’s blues, and that his greatest song should have been the inspiration for Johnson’s greatest), which he played in the hauntingly dissonant “cross-note” tuning that made Skip’s music sound so supernally and indisputably itself. It would be a rare evening that he did not play his chilling Depression-era blues, “Hard Time Killing Floor,” or the mournful “Cypress Grove.” Generally he would present “I’m So Glad,” his “little, tiny” children’s song that Cream covered in 1966, at least once during the evening, explaining that while he could no longer play it as fast as he once had, in “sixty-fourth” notes, he could still perform it in “thirty-seconds.” He would then take the song at breakneck speed and smile at the applause that washed over him. When I wrote to the editors of Blues Unlimited about my recent blues experiences, I always mentioned Skip and cited him as one of my favorite “live” performers. It was always edifying in one way or another to see him—there was never any question that you took something away from the performance, even if it was only a melancholy sense of human limitations, as reflected both in Skip’s music and in his increasingly dour mien.

In 1994 a biography of Skip James appeared. It was called I’d Rather Be the Devil after his most famous song, and it proposed to offer “new insights into the nature of the blues, the world in which it thrived, and its fate when that world vanished.” To do that, the author, Stephen Calt, proposed to demolish the “myth” of Skip James and, by extension, the romantic myth which he suggested had grown up around the blues; he would tell the true story of a bluesman, and the blues milieu, unvarnished and unembellished.

This would certainly be a worthy enough project taken at its face; it is one which was undertaken admirably, for example, by Jeff Titon in his Early Downhome Blues, which explores the origins of the blues, both folk and commercial, and the inevitable intersection of the two in the vernacular culture of their time. Mike Bloomfield’s Me and Big Joe, which tells the tale of the young white guitarist’s adventures and misadventures with Big Joe Williams, would be yet another corrective to the romantic view, cast in a first-person, scatological account not suitable to every taste perhaps but utterly convincing in its mix of love and confusion.

This is not the course that Stephen Calt chose to follow. Instead, he produced a book written out of what appears to be little but fear and loathing. He sets out in fact to systematically attack not just Skip James, a figure with whose achievement the world is scarcely familiar enough to justify such heavy-duty demolition, but everyone whose life Skip James ever touched. Skip himself is, in Calt’s view, “a figurative white man trapped in a black skin,” “cold-blooded,” “obsessive,” and the possessor of a “delinquent lifestyle.” He is misogynistic, “a shameless braggart,” “emotionally stunted,” a gangster and bootlegger who was the plantation equivalent of “a successful drug dealer in a modern-day housing project,” a “rank” exaggerator, “jaundiced,” “humorless,” “predatory,” hypocritical, mendacious, pretentious, and just plain bad.

Lest you think that Skip James was any exception to the general rule of knavery and tomfoolery that was abroad in the land, here are just some of the characterizations that Calt offers of some of the book’s other characters. In the course of the few pages surrounding Skip’s 1964 Newport appearance, we discover Robert Pete Williams “looking like a caricature of a pimp,” a “buffoonish” Hammie Nixon, an “embittered” Jesse Fuller, a “bleating” Fred McDowell whose unnamed wife “had a pop-eyed deranged look,” a “boorishly bragging” Reverend Robert Wilkins, and a “dim-witted” Son House, “a surly drunk [who was] the laughing stock of his neighbors.” (Son House, as much as anyone the inspiration for Robert Johnson’s and Muddy Waters’s style, appears to be a particular bête noire of Calt’s.) And believe me, this is only skimming the surface. On other pages Ishmon Bracey, a contemporary of Skip’s who produced a handful of matchless pre-Depression sides, is a “shameless name-dropper” and a “pest,” Skip’s fellow Bentonia, Mississippi, native Jack Owens an “unwitting bearer of another set of false pretenses” and, perhaps worse, a “derivative amateur”; Skip’s father was “a man of primitive anger,” Bukka White lacks personal and musical integrity, Mississippi John Hurt is another hopeless amateur, without any real talent or pride. And that’s not even getting into all the white people who discover and represent all these “criminals” and buffoons and are even more lacking in integrity and seriousness themselves. Everyone is dismissed, from John Hammond and Alan Lomax to blues record collectors in general (effete “wine sniffers” and “connivers”) to folklorists (racists all) to the Beat Generation (if you want four ways to recognize a beatnik, turn to pages 257–259) to the whole folk movement (greedy, stupid, “pretentious,” and “nonsensical”) to the entire U.S. (“No country could be more inhospitable to the [already dismissed] values of folk music scholars than the commercially oriented society of America, in which what was obsolete was valueless.”)

What are we to make of all this? Why even bother with it at all? you might ask. Well, I suppose for me it was the seriousness with which the book was taken in many quarters—and for that I have no explanation at all. About two-thirds of the way through, though, we begin to catch glimpses of what it is all about, as suddenly the author himself appears, an awkward, “gawking,” eighteen-year-old blues enthusiast, on his way to Newport in 1964 to see his idol, Skip James. In retrospect, he declares, his “infatuation with blues was a solitary, thoughtless preoccupation.” And while he is “intoxicated” when he first hears Skip sing, years later he recognizes “the sentimental, juvenile nature of my joyous excitement [at] the soap-opera triumph of an impaired performer.” The final, chilling judgment? “Had I known how our lives would intersect over the next four years, I would not have initiated that first conversation.”

Is this a “thorough, clear-headed, and insightful” view, as one review had it, “the best book on the subject of country blues for the layperson”? Is it, as even some negative reviews have tended to suggest, a book deserving of respect because it unflinchingly reveals a truth at odds with observation, decency, and common sense? I don’t think so. Not because the book that Calt purportedly set out to write would not have been a fascinating one. And not because there are not occasional nuggets of information, glimmers of idiosyncratic truth as presented in Skip’s own words and views throughout. But the entire book is so colored by the language of indiscriminate rage, the sense of imagined slights so infects its very marrow, that there is nothing left but bile, universal loathing, and utter, and abject, self-contempt. In the end this is a terribly sad book, not because of its subject but because of its author. It may perhaps be deserving of our pity but surely not of our attention or respect.

So don’t look to this book for a picture of Skip James. Look to the music instead. And if Skip, whose work never ceased to proclaim the beauty of what Gerard Manley Hopkins called “all things counter, original, spare, [and] strange,” found himself set apart both from the world of his peers and, in later years, from the moment of time into which he had somehow inexplicably slipped, well, so be it. That was his self-acknowledged lot in life: engrossed in his music, he seemed well aware that he was destined never to fit in.

As Skip himself once declared:

“Now you know sometimes it seem like to me that my music seem to be complicated to some of my listeners. But the one thing that seem to be complicated to me, and that is that they can’t catch the ideas. Now I have had some students that are very, very apt—they can catch ideas very quick—and other children, you cannot instill it in them, I don’t care, no matter how hard they tried. Well, there are some people, they just don’t have a calling for it. Now I might have wanted to do some things I’ve seen other people do and are prosperous at it, and I would like to take it up myself. But it just wouldn’t fit into my life, it wasn’t for me. So the thing that a person should do, seemingly, while they’re young, is to seek for your talent wherever it is at, and then when you find where it is most fit to put it in execution, do that. Well, for myself, I been out traveling ever since I quit school. I’ve had quite an experience at different ages and different times. And that’s the best teacher I found. That’s something they cannot take away from you. Personal experience.”

“Whose Skip James Is This?,” originally published by the OA in 1997, appears in this slightly revised form in Peter Guralnick’s new collection, Looking to Get Lost: Adventures in Music and Writing, which was published on October 27, 2020.

Enjoy this story? Subscribe to the Oxford American.