Miss Gay America: an Arkansas Tradition

The oldest national drag competition hosts its first-ever Femme pageant.

By Caroline McCoy

Courtesy of Author

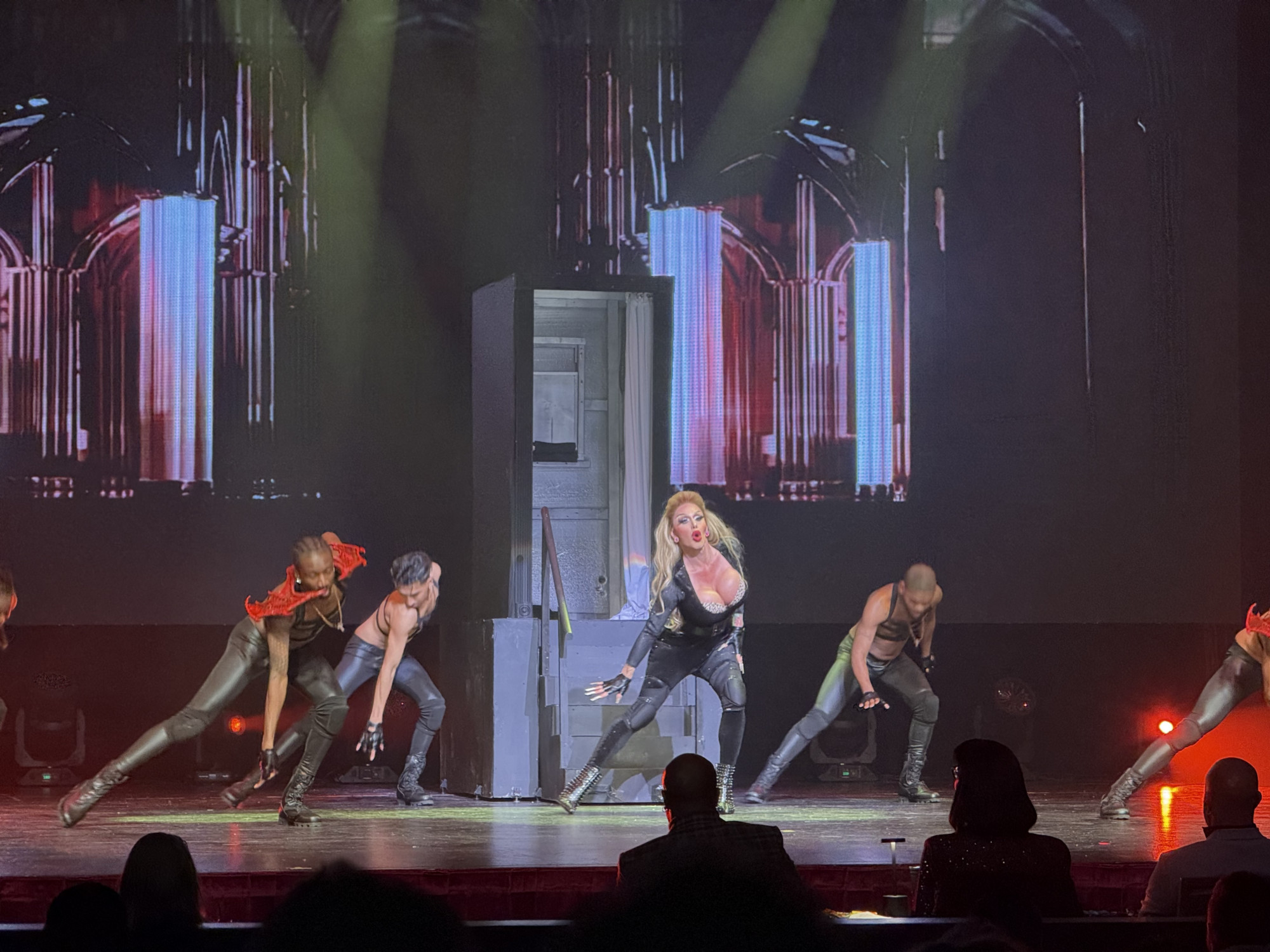

Onstage at the Robinson Center in downtown Little Rock, Dextaci and Charity Case trade commentary to fill time between pageant contestants. Tonight, there are eleven, and each is accompanied by intricate set pieces and dancers, the accoutrements required for a crown-worthy performance. “These girls did not come to play,” Dextaci says. She is speaking from experience, having won the title of Miss Gay America in 2022. Charity Case won in 2001.

As veterans of the oldest drag pageant in the country, Dextaci and Charity Case have spent the past week offering encouragement to this year’s contestants, at times stepping in as masters of ceremonies alongside 2003 titleholder and Miss Gay America board member Dominique Sanchez. Though the banner Miss Gay America pageant concluded on night four, this inaugural fifth-night showcase is devoted to Miss Gay America Femme, a distinct division for trans and cisgender women.

“We’re gonna make history tonight,” Dextaci says. “Our very first Miss Gay America Femme will be crowned right here at the Robinson Center. I’m excited, how ’bout y’all?”

The audience applauds, whistles. This is a room filled with drag pageantry icons and their supporters, many of whom have long advocated for trans representation within the Miss Gay America pageant system, which has enforced strict rules against body modifications below the neck since its inception in 1972. The pageant’s catchphrase—“Where Boys Are Boys and Female Impersonation Is an Art”—is an explicit reference to the purist regulations that have long separated Miss Gay America from other national drag competitions, including Miss Continental, Miss Gay USofA, and the internationally televised RuPaul’s Drag Race, all of which have crowned trans contestants.

“For a while the Miss Gay America system, I think for most people, was kind of old-school pageantry,” says Tracy La Louisianne, the reigning Miss Gay Oklahoma America and a top-ten contestant at this year’s Miss Gay America pageant. Though competition in her division ended last night, she is here to support the women competing for the first-ever Femme title. “I think Miss Gay America Femme is a step in the right direction, to welcome our trans sisters, to be more inclusive, and to showcase that style of the artform of drag,” she says.

Courtesy of Author

In recent years, Miss Gay America and its owners have faced criticism from the drag community not just for being “old-school” but transphobic. Under the pageant’s physical qualifications for entry, many would-be and former Miss Gay America contestants have been barred from competing in the pageant and its preliminaries after starting their transitions.

“Many of our friends are trans individuals,” said Rob Mansman, who bought the pageant with his husband Michael Dutzer in 2016. In their first year of ownership, Mansman and Dutzer began to hear a common sentiment from these friends and others within the community: “[they] say the one regret they have of transitioning when they did was not being able to win the title of Miss Gay America before they transitioned.” Neither Mansman nor Dutzer is trans, so they reached out to friends and colleagues who are, people who could help them respond to the community’s needs. “We made sure to add two members to our board that were trans,” Mansman said. “So that the representation was there.”

This year’s Femme division was born out of such collaboration, and, with its introduction, Mansman and Dutzer said they are expanding the legacy of Miss Gay America. In other words, they have not amended the parent pageant’s guidelines to include trans and cis women but created a space for these performers to compete. This solution, while broadly celebrated, sits at the intersection of two objectives: to uphold the pageant’s legacy notions of body and gender, and to pioneer a future that is free from them.

Courtesy of Author

Whether the Femme division is a concession to the past or a departure from it, Mansman and Dutzer are undoubtedly committed to honoring Miss Gay America’s fifty-three-year heritage. This is, in part, why they selected Arkansas as the destination for the annual pageant. “It had roots in Little Rock for quite some time,” Dutzer said, referring to Norman Jones, a.k.a. Norma Kristie.

In 1975, three years after winning the inaugural Miss Gay America crown in Nashville as Norma Kristie, Jones, a lifelong resident of Arkansas, purchased the pageant and established its home base in Little Rock. The pageant continued to travel under his thirty-year ownership, crowing annual winners at venues across the country; but Miss Gay America became an evolutionary force in Arkansas’ deeply rooted drag scene, which had, by the early 1970s, evolved from the rural folk dramas of the first half of the twentieth century into a haven for queer community. As Jones grew the pageant’s national reputation, he was also working to elevate drag in his home state, opening night clubs and show bars, including Discovery and Triniti in Little Rock. These new gathering spaces expanded opportunities—and competition—for drag queens in the state, enabling top performers to compete locally in Miss Gay Arkansas America—the oldest preliminary to the parent competition—and on the Miss Gay America national stage.

Reigning Miss Gay Arkansas America, Coppa LeMay, who first competed in the state in 1988, said that under Jones’s early leadership, the Arkansas preliminary was considered among the top-four feeders to the national competition. Though LeMay left Arkansas in 1989—first for Dallas and then DC, where she not only continued performing but also embarked on a twenty-five-year career as a legal administrator—she returned with a desire to help restore what she saw as a dwindling interest in the Miss Gay America system. “I just saw a lack of enthusiasm and a lack of drive,” she said.

Since winning the Miss Gay Arkansas America crown, LeMay has been working with the pageant to recruit contestants and add three local preliminaries to the state competition. One of these, Miss Gay Elegant Arkansas, will honor the life of Paige Fox, a former Miss Gay Arkansas America and mentor of LeMay’s. “Paige was the only Black influence that I had when I started,” she said. The pair met when LeMay was sixteen (Fox was a youth minister at the time), but their friendship began years later at the 1987 Miss Gay Arkansas America pageant, which Fox won.

The central role of any state or national titleholder is to celebrate legacy performers and recruit new ones. It is also her job to forge a path for future queens, acting as mentor, friend, family. In Arkansas—where Miss Gay America has its longest lineage and where, as recently as 2023, the government presented but ultimately did not pass anti-drag legislation—pageant winners have helped preserve the artform. At age sixty, LeMay is aware that she is carving a legacy through her impact on up-and-coming local performers, providing the kind of mentorship that she received from Paige Fox, from Norma Kristie, and others. This year, at the first-ever Femme competition, LeMay supported Arkansas performers Tatum Totts and Fonda LaFemme from the front row.

Miss Gay Arkansas America, Coppa LeMay, courtesy of Julie Gayler Photography

For the uninitiated, pageants are lengthy affairs. Miss Gay America extends over four days and nights, with the top ten competing on night four, which can run as long as six hours. This year, New Orleans-based performer Ivy Dripp earned the Miss Gay America title after what both Mansman and Dutzer described as the closest scoring by judges in their history of ownership. She was crowned close to midnight before being ushered to the Arkansas drag institution Triniti Nightclub by Coppa LeMay in celebration. Which is all to say that fatigue is unavoidable for these performers. And yet, at the first-ever Femme competition, as contestants showcase their talents and eveningwear and interview skills, participants from the parent pageant fill the audience. Tired as they are, they are here to support their expanding sisterhood.

“I’m just so proud that they put themselves out there for this first Femme division,” says Morgan Morgan Morgan. As a show of solidarity, she and her fellow Miss Gay America top-ten finalist Keirston LePaige arrived in full drag. “I have two people in the competition tonight,” says LePaige. “My first gay drag mother is competing—Mokha Montrese—and then a very dear friend of mine, Chevelle Brooks. . . . So this means a lot to me, to be here for them.”

All eleven performances are distinct. An aerial acrobat spins on wide, white silks. A vocalist costumed in a French-looking negligée belts “Don’t Tell Mama.” A dancer leads a full company to a medley of Janet Jackson songs, bringing most audience members to their feet. One contestant, Hypoxia, blends spoken-word, video, song, and dance to tell her transition story. Later, during the interview portion, she reveals that on this very night she is celebrating three years of sobriety. More than once, a contestant references the lifesaving impact of drag. When the winner, Naomi St James, receives her crown, she cries for the eighteen years she spent dreaming of competing for the Miss Gay America title before the Femme division gave her a chance.

This theme of struggle undergirds what is otherwise a night devoted to joy, talent, and the persistence of self. “At a very early age, I knew who I was,” says Fonda LaFemme, crediting both her biological family and her drag family with supporting her through her transition. Chevelle Brooks describes performing amid a debilitating illness that required her to wear a colostomy bag. “Through all of that,” she says, “I still remained Chevelle Brooks. Because I love doing drag. Even with a colostomy bag, I was doing what I love to do.” In a speech devoted to gratitude, Naomi St James reminds the crowd that “this old broom still sweeps.” And in a private interview with the Oxford American, Hypoxia makes certain plans for next year. “I will be back,” she says. “I’ve caught the pageant bug.”

Less than forty-eight hours remain before the 2025 presidential inauguration, before the administration will rescind federal recognition of transgender people.