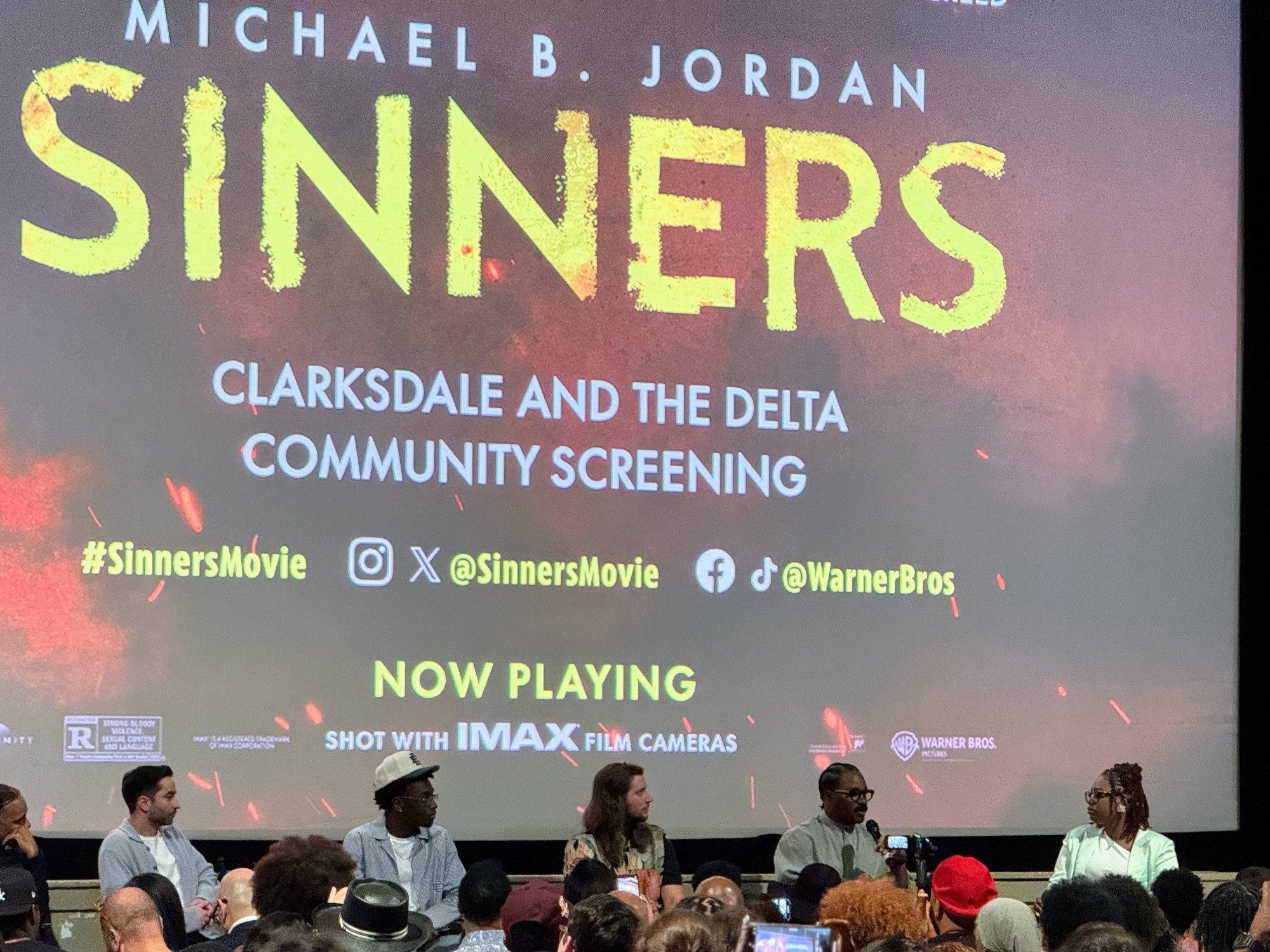

The New Roxy in Clarksdale, Mississippi. Photograph by Caroline McCoy

“Sinners” Comes Home to Clarksdale

After campaigning to get Ryan Coogler’s film screened in the town where it’s set, local organizers turned the spotlight on their own creative economy.

By Caroline McCoy

On May 29, Sinners, Ryan Coogler’s hit film about vampires and blues, arrived in Clarksdale, Mississippi, the city that inspired it. Coogler attended the premiere screening, alongside actor and musician Miles Caton, who plays Sammie, composer Ludwig Göransson, producers Sev Ohanian and Zinzi Coogler, music producer Lawrence “Boo” Mitchell, and musicians Cedric Burnside, Tierinii Jackson, and Bobby Rush. The group also participated in a post-screening Q+A, during which Coogler shared a behind-the-scenes anecdote about Rush, the three-time GRAMMY-winning bluesman who was both a musical consultant on the film and the harmonica player behind the sounds of Delroy Lindo’s Delta Slim.

As Coogler told the story, he had gathered several musicians in Mitchell’s Memphis studio to discuss his vision for the film. “Mr. Rush is looking me, like, dead in my eyes while I’m telling this vampire story,” Coogler recalled. “I don’t know if . . . when I get done, he’s gonna get up and, like, walk out or what. And I got done, and he was like, ‘yeah I knew a vampire.’”

Coogler loved the line so much, he wrote it into the script. (Delivered by Lindo, it has since emerged on social media as a fan-favorite Delta Slim moment.)

Rush, who will be ninety-two in November, is beloved in Mississippi. Last year, his hometown of Jackson named a boulevard in his honor. Though he plays at venues around the world, he is a mainstay in Clarksdale, where Sinners takes place and where a blues tourism industry keeps venues like Red’s and Ground Zero in business. “Bobby is a walking encyclopedia on the blues,” said Jake Carter, a musician who drove from Jackson to attend the Sinners premiere. “He’s a guy that’s lived.”

Rush said that some of that living was realized onscreen, thanks to Coogler’s movie. During the Q+A he spoke directly to the filmmaker about how deeply he identified with Sammie, a young blues musician trying to make his way in the Jim Crow Delta. “This movie seemed like it was about me,” Rush said. “I remember working in this town—myself and Muddy Waters, 1949—and we had to work down in Alligator because we couldn’t work in certain places here because we were Black. . . . I remember those days and this reminds me that you know that. You did it for us.”

These exchanges between musician and filmmaker spoke to the layered authenticity of Sinners, which not only features music by Rush, Burnside, and Jackson but also Clarksdale’s own James “Super Chikan” Johnson and Christone “Kingfish” Ingram, the twenty-six-year-old guitar phenom who began playing local clubs when he was in the seventh grade. (He has also toured with Buddy Guy, who plays the elderly Sammie in Sinners, and makes a cameo during the film’s final scenes at Pearline’s.) The infusion of these musicians into the film’s score and artistic ethos grounds Sinners—a movie set nearly a century ago and propelled by supernatural elements—in a recognizable sense of place, a Clarksdale that several locals told me feels as resonant with the city’s present as with its past. After all, Coogler’s depiction of the region’s historical blues idiom is intentionally informed by its contemporary version. And while he takes aim at the exploitation and cultural extraction the Delta and its musicians have experienced (the vampiric metaphor is hard to miss), he reflects art and enterprise as tools of resistance, of community and economy building in defiance of the myriad threats at the door.

Ryan Coogler speaking at the Sinners premier in Clarksdale. Photograph by Caroline McCoy

The creative and entrepreneurial energy embedded in Coogler’s Clarksdale is not an imagining but a reflection, and it is the essential reason for the ceremonious arrival of Sinners to the city nearly six weeks after its theatrical release. Clarksdale has no movie theater. Delta Cinema, on Third Street, shut down in 2003 and remains uninhabited, while the once-segregated Paramount and the former Black theater, The New Roxy, have been repurposed as an arts hub and music venue, respectively. Moved by the film but frustrated by its inaccessibility to many in their community, a group of organizers, business leaders, and creatives—spearheaded by Tyler Yarbrough of the agricultural nonprofit Rootswell—launched a campaign for a public screening in Clarksdale. In an open letter addressed to Coogler, Michael B. Jordan, and the cast and crew of Sinners, Yarbrough wrote, “it’s clear you did your homework. The love you have for Southern folk, Mississippians and Clarksdale came to life through your commitment to writing us right.” (Alluding to the demographic complexities of the Delta that Coogler captures in Sinners, Yarbrough later said that he wrote the letter during a visit to the nearby Choctaw reservation.)

Within days, the Clarksdale-born journalist Aallyah Wright of Capital B News had escalated Yarbrough’s petition to a national scale. Soon afterward, Warner Brothers and Coogler began working with Yarbrough, the Jackson-based media group ’Sipp Talk, and other area organizers to bring Sinners to the place that inspired it. This is how, for three days, the Clarksdale Civic Auditorium became the local movie theater, showing Sinners at regular intervals after the initial premiere and Q+A, which was moderated by Wright (Capital B News also served as an event sponsor).

The interview began with the question that had been on the minds of locals: Why hadn’t a movie set in Clarksdale been filmed in Clarksdale? Coogler said that he shot the film in Louisiana—largely on soundstages—because the state offers existing infrastructure and better tax credits to film productions. Producer Sev Ohanian and Nina Parikh, director of the Mississippi Film Office, who was also in attendance, said that they had spoken early on about the possibility of shooting in Clarksdale and that they hoped the success of Sinners would open new opportunities for filmmaking in the area.

Asked to share advice for young Mississippi creatives, some of whom sat in the audience, Coogler said that while he had grown up in Oakland, California, with access to resources, he was influenced by the self-sufficiency modeled by his grandfather and uncle James, both Mississippi men who, despite not being professional contractors, built the home that remains in Coogler’s family using scrap wood. “The thing that you guys have, you know, is the thing that can’t be taught,” he said.

Ohanian offered more explicit advice, advocating for lateral networking within communities and building skillsets through formal and informal education. But he also spoke to Coogler’s point about the enterprising spirit of Mississippi creatives and the uniqueness of the Delta. “You guys have to capitalize on what you have. . . . We had to go make a whole-ass stage and set to make it look like this place. You guys are already here. There’s so much energy here, so much magic here and culture here. Find ways to capitalize on that. Tell your story. And honestly, guys, I think the whole world is watching right now.”

The shuttered Delta Cinema in Clarksdale. Photograph by Caroline McCoy

The shuttered Delta Cinema in Clarksdale. Photograph by Caroline McCoy

This would become a regular conversation point of the weekend: how to expand Clarksdale’s creative industry to appeal to diverse tastes and audiences.

That the world is watching Clarksdale was not news to Yarbrough and his collaborators, who used the Sinners premiere as a starting point for deeper conversations about their city’s creative economy. From Thursday, May 29 through Saturday, May 31, in conjunction with the film screenings, all of which were free and open to the public, event organizers hosted tours, talks, performances, and panels that spanned the day and bled into the night. Among the locals, visitors, and press in attendance, FOMO was a shared experience. No single person could attend everything on offer. Immediately following the Q+A, several members of the press accompanied local leaders and the Sinners cast and crew on a tour of Clarksdale that culminated at the Morgan Freeman-owned Ground Zero Blues Club, where Kingfish played for the crowd.

Meanwhile, at Red Panther Brewing Co., others gathered for a post-screening “AfterTalk,” a casual mingling of regional artists, event organizers, and Sinners fans. At a picnic table on the brewery patio, Jackson-based musicians Jake Carter and Twurt Chamberlain spoke with me about the film’s resonance with their own experiences as young musicians. Chamberlain, who is thirty-three and having a career-defining year with the release of both an album and a documentary, said that he plays traditional venues, “but my claim to fame is the sidewalk.” He said he related to both Sammie, as a traveling musician, and to Delta Slim, who is introduced in the film as a street performer. After the Sinners screening, he said, “I sat there on the sidewalk and played. There was a crowd that formed around me. They don’t have to stop. . . . There’s so much power in playing music on the sidewalk.”

Both Chamberlain and Carter talked about honoring and respecting the blues, though they distinguished the traditional style from its contemporary manifestations, noting generally that white and tourism audiences tend to gravitate toward the old, while Black and local audiences are more drawn to Southern soul. Chamberlain’s genre-blending style has been called Country Punk Black, a description that he adopted as the title of both his first album and his documentary. This would become a regular conversation point of the weekend: how to expand Clarksdale’s musical industry to appeal to diverse tastes and audiences, particularly when it comes to young people. With a soundtrack that blends gospel, blues, jazz, soul, funk, and Irish folk music—along with a standout dance scene that traverses time and cultures—Sinners counters any impression that genre is static. And yet, there is an understanding in Clarksdale, particularly among cultural educators and youth program leaders like Chandra Williams, the executive director at the Crossroads Cultural Arts Center, and Rebekah Pleasant-Patterson, the executive director of Griot Arts, that many of the city’s young people feel excluded from or even befuddled by the blues, a genre that some argue has been intellectualized to an unrelatable, culturally dissonant degree.

Also at Red Panther Brewing Co., Jasmine Williams, the founder of the Jackson-based media company ’Sipp Talk and one of the event’s organizers, reflected on her own experience as a creator who feels called to tell Mississippi stories. Williams, who grew up in the eastern city of Columbus, spent several years in Austin, Texas, but she missed an emphasis on innovation and collaboration that she said feels unique to her home state. “Mississippi is kind of like a blank canvas. We can build whatever we want to here. And a lot of people are doing the work, even while people aren’t looking.” Still, Williams recognizes the challenges of sustaining a creative industry in many parts of the state, including the Delta, where resources are limited and outsiders tend to take more than they give. “Mississippi is different, and people don’t know it because they just have this idea that was given to them, like in mainstream, about who we are.” Sinners, she said, has provided a counterpoint to such outsider narratives, and it will ideally spur deeper investments in authentic regional stories. “When we get those moments where people have their eyes on us, I just want people to be more careful with Mississippi.”

Jackson-based musician Twurt Chamberlain performing in Clarksdale. Photograph by Caroline McCoy

“In Clarksdale, we take what we got and make what we need.”

Blues Musician Edna Nicole (and her mother, Brenda Luckett)

That the Sinners festival coincided with a previously planned tribute weekend to Son House, the Lyon-born musician, caused some concern for Bruce “Dr. B” Weinraub, a physician, piano player, and owner of the Blue Room, an event space on Third Street. Weinraub, who organized the Son House tribute weekend, had invited Joe Beard and John Mooney to headline the event, which also featured a screening of and panel discussion about the 2016 documentary Two Trains Runnin’. On Thursday evening, at a reception at the Blue Room, where Joe Beard jammed alongside the Macon, Georgia, musician Angel “Cash” Ocasio, Weinraub said that he hoped people who came out to experience the Sinners events would also take time to get to know Son House and his contribution to the Delta blues. “It’s all related,” he said.

Mississippi-born Beard, who is eighty-seven and a staple of the music scene in Rochester, New York, said that his visit to Clarksdale was his first in a long time. He’d come to honor House, his former neighbor and friend. He had not yet seen Sinners but was pleased that another one of his friends, Buddy Guy, appeared in the film. By Saturday evening—his headline event—he would be playing alongside John Mooney and Clarksdale’s own Big A at Ground Zero, where it didn’t matter which festival had drawn the crowd.

At Red’s, a juke joint started by the late Red Paden and owned by his son, State Representative and Mayor-Elect Orlando Paden, Clarksdale-born musician Edna Nicole played to a crowd of locals and tourists from places as nearby as Memphis and as far away as Italy, Holland, and Sweden. Amid a set that included covers of “Dust My Broom” and “Mustang Sally,” Edna Nicole invoked her mother’s saying—a phrase that encapsulated the spirit of the weekend—“In Clarksdale, we take what we got and make what we need.”

The author, scholar, and OA contributor W. Ralph Eubanks, who attended the weekend as both a panelist and Sinners fan, told me later, “My son swears that that juke joint scene in [the film] felt like Red’s.” A Mississippian whose newest book, When It’s Darkness on the Delta, will be released in early 2026, Eubanks became a fixture in Clarksdale during the summer of 2023, when he was living in and researching the city. Among the many locals who informed his work is Keith Johnson, the grand-nephew of Muddy Waters, who was playing at a newly opened venue called The Matchbox, where Bobby Rush also made an appearance. Eubanks said that it was Johnson who brought him to an annual community gathering of Delta musicians in Glen Allan, Mississippi, back in 2023. The day resonated with Eubanks as a catalyzing moment of creative resistance to the commodification of regional music. He recalled the musicians saying to one another: “We got to come back. None of us live here anymore. None of us can make a living here anymore. We’re scattered to the four winds, but we have to come back here to claim the space as ours.” Eubanks said that he saw Sinners reflecting this movement. “Smoke and Stack are protesting the circumstances that they have to come into. I mean, they buy this place—it’s a killing floor—and they’re creating a place to feel free. That’s the ultimate protest, reclaiming a space. And I think that’s what’s happening right now. People are reclaiming this place.”

Such were the themes of the festival and the conversations brought to the fore through the popularity of Sinners. During the panels that followed—discussions about “Building a Blues Economy Rooted in Dignity;” sustainable agriculture and food networks; the legacy of Black placemaking in Mound Bayou, Mississippi; recognizing the cultural impacts of Choctaw and Chinese Americans on the Delta; and building a Mississippi film workforce—an intergenerational collective of leaders and experts shared ideas and spoke out against the kind of gatekeeping that often arises in artistic spaces.

There was, too, an interest in confronting the challenges of living and creating in an under-resourced place. Clarksdale is home to fewer than fourteen thousand people, forty percent of whom live in poverty. Representative and Mayor-Elect Paden, the owner of Red’s who sat on an economic panel, spoke of government investment in infrastructure, particularly the road system, which would improve highway access and enable more businesses to locate in the Delta. Chandra Williams, of the Crossroads Cultural Arts Center, advocated for subsidized funding for the artists that keep Clarksdale’s tourism business afloat. Edna Nicole (of Thursday night’s Red’s fame) also addressed the issue of compensating artists. Like other area musicians, including Lee Williams, who sat on the economic panel, she works at the Delta Blues Museum, where roughly eighty-five percent of visitors are international. “We have to sell Clarksdale to the world, but we also have to sell Clarksdale to Clarksdale,” she said. “Clarksdale has always been a big deal.” Ensuring that it stays that way means compensating the artists who sustain and grow its legacy.

In the three-day event galvanized by Sinners, the film functioned as a reference point. As popular movies tend to do, it served as fictional shorthand for real-world questions and possibilities. Eubanks returned to the image that more or less bookends the film: Sammie clutching his guitar, refusing to drop it despite his preacher-father’s pleas. “He does not let that go,” Eubanks said. “That’s because the blues is his religion. The blues saved him. That guitar saved him.” It is a scene that speaks to the self-determination Coogler saw in Clarksdale’s past and present, and it reflects what Eubanks views as a contemporary imperative: “This is the moment to reclaim the blues as a means of protest,” he said. It is also a moment to reclaim Clarksdale and to ask, as several panelists did during the course of the festival, What is missing in the popular understanding of our city? The answers may shift with time, but the consensus was clear. “We are in the place,” Chandra Williams said. “If a narrative needs to be changed . . . we are the ones.”

Support the Oxford American

The Whiting Foundation will double your donation—up to $20,000.

Your donation helps us publish more work like the article you're reading right now. And for a limited time, every gift will be matched up to $20,000 by the Whiting Foundation.

Prefer a subscription? You'll receive our award-winning print magazine—though subscriptions aren’t eligible for the match.