A BEAUTIFUL DARK

By Armando Alvarez

When I photograph my subjects, I do not set out to construct a narrative, though each photograph ends up marking moments and landmarks from my life. Not that I’m documenting everything that happens to me—on the contrary, if something or someone moves me enough to shoot a picture, I let it happen.

On rare occasions, an idea will pop into mind that I’d like to see interpreted in a photograph, moving me to begin a project or a series of photos. Sometimes these ideas develop for weeks, months, or even years before I finally see them come to fruition. These projects can be just as rewarding as a photograph of a fleeting moment.

When I began to seriously pursue photography, my personal reservations kept me from photographing people, so I trained myself to “see” what was all around me, to look further into the urban landscape with the knowledge that there is much to see for those who are willing to look.

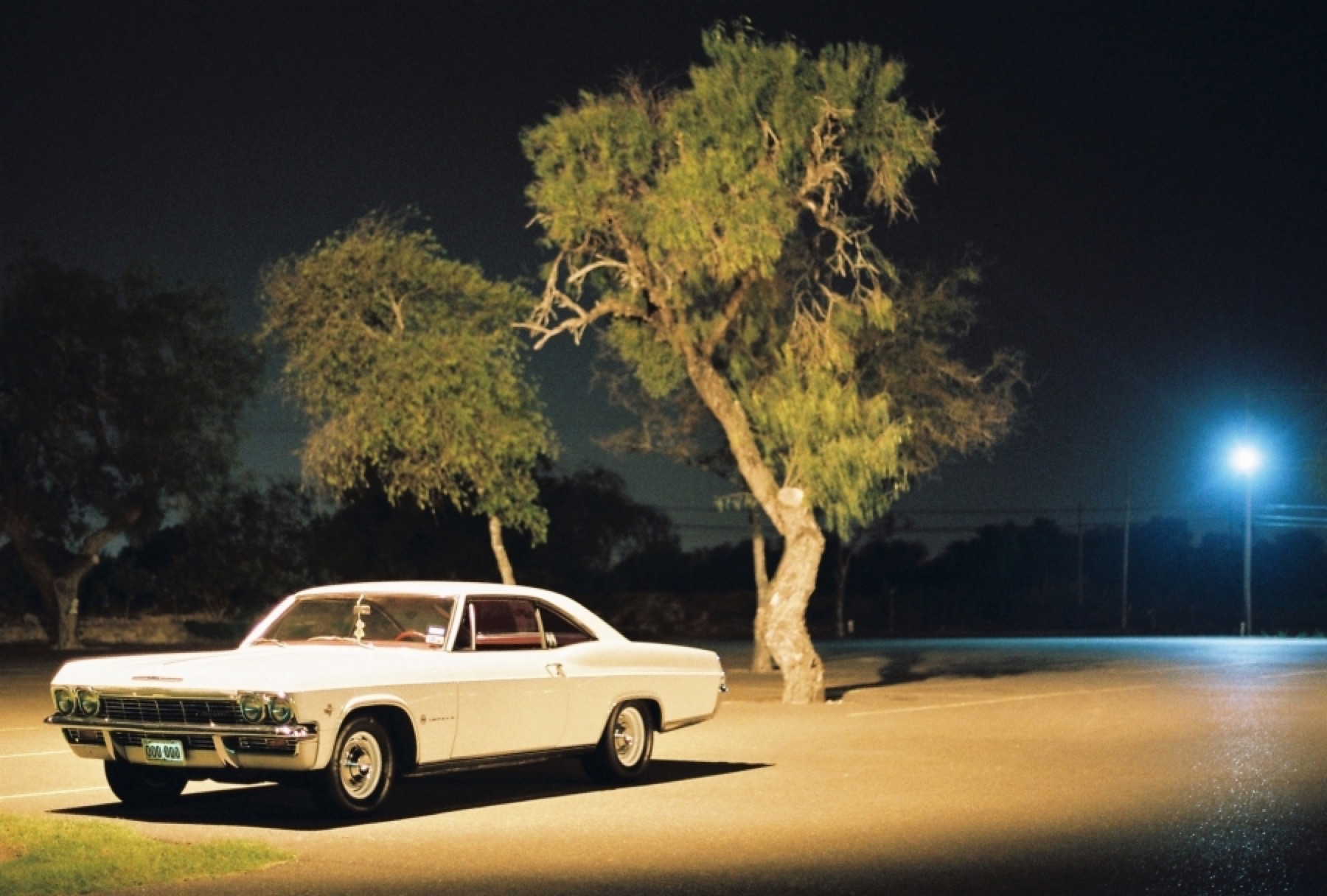

I began to explore static subjects—namely automobiles and other subjects at night. I believe the automobile says a lot about the social aspects of each subculture within geographic areas of the United States. Photographing static subjects using long exposures at night adds a dynamic aspect to everything in the frame: the trees, the night, the light source (or lack thereof). A beautiful dynamic darkness. My son once described this series of night-long exposures as “a beautiful dark.” I love that.

While I have nothing against digital media and digital photography, I choose to work solely with older film cameras in 35mm and medium format. I prefer a slow and focused process to the immediate click of a shutter, and whenever possible I prefer shooting in manual mode and manual focus, in color, with a tripod and available light. Shooting film allows me to choose not only my subjects with careful discretion, but also the time of day or night when they will look their (subjective) best. And my editing is minimal to nonexistent. This is a highly subjective preference, and varies with every artist. I choose to let the emulsion of my chosen film do the work.

It’s important to me that the viewers of my work construct their own narratives—their own stories—from what they see in my photographs. I don’t like to volunteer information about each photograph as it may ruin what that particular work means to the viewer. (Likewise, I hope my favorite musicians will avoid explaining the lyrics and meanings of my favorite songs.) This is what I find fascinating about photography: the unspoken interaction between viewer, subject, and photographer.