Tasting Indian Creek

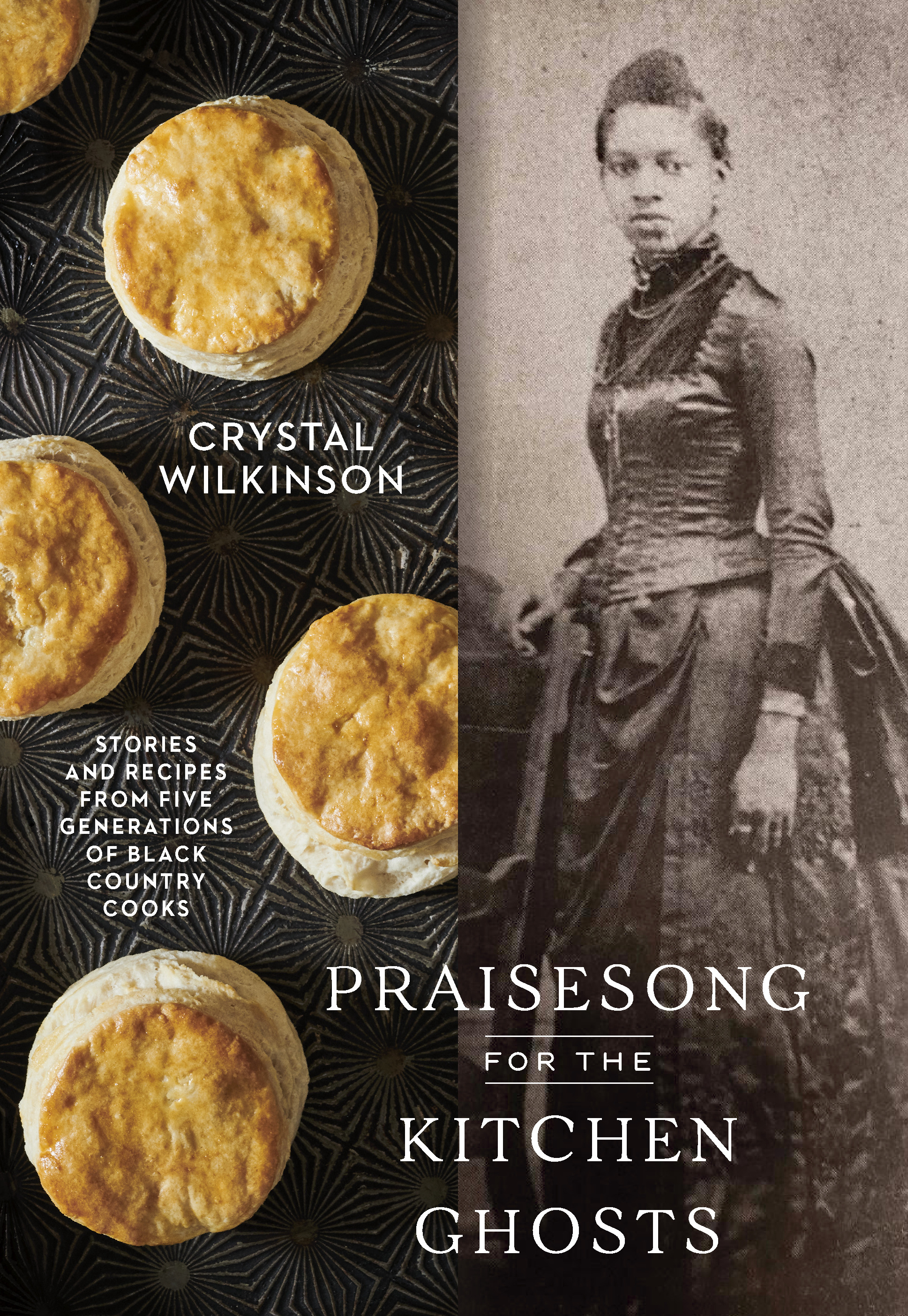

Excerpted from Praisesong for the Kitchen Ghosts

By Crystal Wilkinson

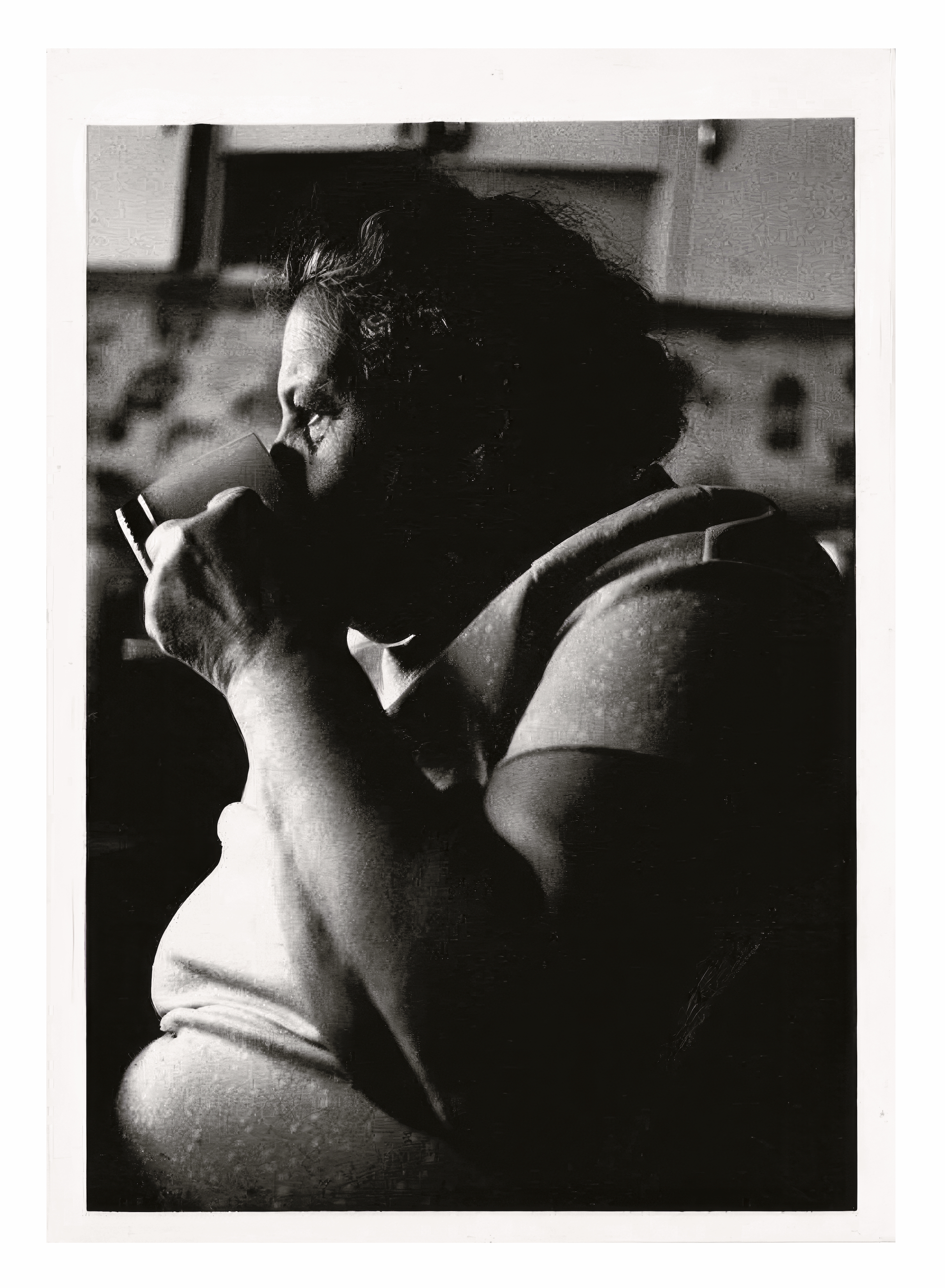

Granny Christine in her kitchen drinking coffee. Photo by Crystal Wilkinson. Courtesy the author

I lived on Indian Creek with my grandparents after my mother suffered a nervous breakdown. Within my family unit, wedged between my grandparents, long after my aunts and uncles had left home, long after my mother had recovered from her second nervous breakdown and moved to Lexington to live permanently, I felt like I belonged to no other place and to no other people. This was, of course, due to the stories my grandparents told and a deep generational sense of belonging to the land.

Passed-down family story says that when my enslaved ancestors were freed, one of our enslavers deeded to his laborers (many of whom were his offspring) land along what is known now as Indian Creek Road. That raised the ire of local white folks. I don’t know this to be true and can’t find any proof of it, but I’m a storyteller, not a historian, and this notion has always intrigued me. What I do know is that my grandmother’s father, Daddy Joe, deeded my grandfather land shortly after my grandparents married in 1929 and started a family.

My grandfather often boasted that he could take me to the place he’d been born, and I held his hand many times when I was a girl as he walked me across a plank on the shallow end of the creek, into a field, and showed me the place where his mother had given birth to him, where a house once stood. He pointed to the spot that just looked like part of the field to me. He looked down at me with pride and then stared at his birthplace with a wistfulness that I’ve never forgotten before we continued to the barn to check on the horses and the cows. I, too, still hold a longing for that land in my blood.

My grandmother had been born nearby, too, but she never pointed out the place to me. She spoke lovingly of advice from her mother. Occasionally she’d point to a tumble of wood and weeds and say, “That’s Aunt Frances’s old place” or “I believe the old barn was over there” or “When I was little we used to swim right up there” or “That’s where the house was before we lost it to the fire.” But most of my memories of her are nestled in the growing, the cooking, the preservation of food.

Hoeing the garden. Stroking the long necks of the yellow squash. Stirring butter beans in a pot. Pouring hot bacon grease over new lettuce, onions, and cucumber. Canning runner beans.

Every morning of my childhood, my grandmother donned an apron and cooked breakfast. Slow. Precise. Deliberate. She equated food with love, and she cooked with both a fury and a quiet joy. She fried bacon, sausage, or country ham. She scrambled eggs. The eggs came from our chickens. She made biscuits from scratch. The lard was rendered from our pigs. The milk from our cows. She rolled out the dough and threw flour into the air like magic dust. She churned butter, made the preserves from pears, peaches, or blackberries that she had harvested herself.

Not long after I entered school, Indian Creek’s Black population was waning. Me and my two cousins were the only Black children in the school, and we sometimes bore the brunt of racist encounters. But at home, it was affirmed that we’d been in this community since the beginning, and I felt as if the old-time people were alive and amongst us every time my grandparents said their names. The Pattons, the Wilhites, the Wilkinsons, the Napiers. They worked and loved and cherished this little piece of God’s earth in Casey County. Poor whites and Blacks mingled some, they helped each other out when it was necessary, and often it was necessary due to harsh weather and rough terrain, but mostly there was a dignity and a sense of a cooperative Black community that was a solid part of my upbringing in this Black enclave, as it had been for my mother and her siblings and those who’d come before.

My line extends from Aggy (my fourth great-grandmother) to Lizzie (second great-grandmother) to Lillie (great-grandmother) to Christine (grandmother) to Dorsie (mother) and Lovester (my aunt) to me and our children. What I know of my foremothers and forefathers from sparse documentation has been augmented by passed-down story and my own communion with the ancestors.

Patsy Wilkinson Riffe, my great-great-aunt, daughter of Aggy and Tarlton, born in 1818 as a free woman of color, is the most famous Black woman from my home region. She purchased her own husband, William Riffe, an enslaved man, and together they acquired a vast amount of property and established a life for themselves that was in great contrast to other Black lives of their time. Patsy built an attachment to her home and established a hunting lodge, which housed many boarders seeking to come to the wilderness. The area they owned and lived in is still called Patsy Riffe Ridge today.

Lillie Patton Wilkinson, my grandmother’s mother, was born in 1889 and died of heart disease in 1939, just a month after my mother was born. She was an emblem of hard work, gathering water from the creek daily. She taught my grandmother the value of a soft tongue and well-cooked food.

My grandfather was a tobacco farmer and also raised corn, pigs, and cattle. He farmed the old way with horse-drawn equipment well into the 1980s and early 1990s. He made sorghum molasses, witched wells, and was a devout member of his church.

A studio shot of young Crystal. Photo courtesy the author

Born in 1915, my grandmother Christine married my grandfather in her early teens. She tended the farm, two gardens, and livestock while also raising two sons and five daughters. When she wasn’t toiling her piece of land, she labored as a domestic, cooking for both her own large family and the families of her employers. She worked almost until the day she died in 1994, and I still conjure her wielding a stirring spoon and butcher knife, not just simply providing sustenance but something more. In the corner of my grandmother’s kitchen, spirits shimmered near the bucket of well water, hovered over the olive refrigerator, floated above the flour sifter, and glided around the coal-burning stove. The dead danced, both protecting and cajoling. My grandmother told me of the haints she’d seen and the ones she remembered. She told these stories at suppertime while we were cooking. She lofted her mother’s apple cakes to myth. I imagined food that tasted so good that it was like nothing I’d ever experienced. My grandmother told me that women were expected to maintain the lineage, to strive to make dishes that rivaled their mothers’. She held long-necked yellow squash as gently as babies. Her own desires to be a schoolteacher, to travel the states, were doused in favor of making her parents happy and marrying young. When she walked gingerly carrying a large pot, when she hefted a ham during hog-killing time, when she placed her hand over her mouth and laughed, she looked like a child in a grown woman’s body even when she was old. Sometimes my grandmother grew sullen and a scowl came over her face while we cooked, but when she looked into the corners of the kitchen, up toward the ceiling, her face fell into soft satisfaction before she took up the knife to scrape a corn cob clean or to grind cabbage for slaw.

These days I often wonder how many of our stories are true, how many are imagination or misplaced longing, but I refuse to believe that my grandmothers were just ordinary women who lived, then died, forever lost to me. Somehow we are all still connected through both the toil and pleasure of kitchen labor. I’m closer to them when I cook. I become them when I cook.

The Indian Creek I knew no longer exists. The farm has been long sold to white people. I drove there recently and felt a deep and unshakable pain. The very landscape has changed. The erosion of the creek has eaten away at my grandfather’s bottomland. There is a long, high fence around the absence of my grandparents’ welcoming driveway. No gardens. I’ve been told that much of the land has been bought by militia types seeking to be further off the grid. There are no Black people there now. My grandparents are gone. So is my mother and four of her siblings.

We are the kind of family where cousins are so close they become siblings. I talk to my cousins Trish, Darlene, and Debra every week and occasionally to others among my grandparents’ twenty-five grandchildren, my uncle Sherman, scattered distant cousins, and other kinfolk.

Crystal and Granny Christine in front of Aunt Tannie’s smokehouse. Photo by Florence Weathers. Courtesy the author

Cousin Debra calls, tells me there are green tomatoes at the farmers’ market. She still lives in a small town near our homeplace. I live forty miles away in Lexington. Sometimes I drive eighty miles round-trip and buy vegetables sold by my cousin George Allen and his wife, Susie, who own a farm. On the Miller’s Farm Facebook page, which is as beautiful as any parental brag book, they post pictures of their bounty. They boast of heirloom tomatoes, cucumbers, cantaloupe, beans, squash, and zucchini. They are carrying on the tradition. Black farmers are nearly extinct.

Me and Debra tell a story first.

“Remember Granny cussing?”

“Yes, whispering like she was a child doing something bad.”

We laugh loud at things that few would understand. We tell half stories because, after all these years, we both know what comes next. Occasionally we’ll reach back and remember something that the other never knew about our old-time people.

When I laugh, she says I sound like Granny.

“You look like her,” I say, and she says, “That’s what Mama says.”

“You’re built just like Granny,” I say.

We sigh, get quiet until we slip back into the laughter again.

When the quiet returns, Debra says, “Tell me again how you fix greens without fatback?”

I tell her:

First you sauté the garlic and onion in vegetable oil in a pot. Then add a pinch of red pepper flakes. Salt. Let the vegetables soften. Wash the dirt from your greens. Slice them longways in ribbons with a butcher knife. Put them in the pot one handful at a time. Cast iron works best. Let them cook down. Sprinkle only a bit of water if they are about to scorch, but sometimes I add vegetable or chicken broth to get them closer to the traditional dish. I like them with some heft in their bite now, not cooked all day.

At night, when he’s not working for Toyota, Cousin William is a chef in training. Right before Thanksgiving, he contacts me on social media and needs our grandmother’s jam cake recipe. I send him a photograph of the recipe in her handwriting.

Our grandmother writes in her perfect cursive:

3 sticks of butter, 2 cups sugar, 2 cups flour, 6 eggs, 1 tsp soda, 1 tsp cloves, 1 cup buttermilk, 1 cup raisins, 1 cup pecans, 1 cup peach preserves, 1 cup blackberry jam, 1 tsp cinnamon. Cream butter and sugar well. Add your eggs. Stir soda in buttermilk. Add flour alternately with milk. Flour raisins and nuts (add them last). Add jam and preserves to your butter, sugar, and eggs mixture. Cook two hours in a 350-degree oven.

“On my way to the store,” William says. “I’ll send pictures.”

I still bake her jam cake with caramel icing at Christmas, though no one in my immediate family likes it. Jam cake is dense and moist. The earthy spice from the cloves and cinnamon, the tartness of the blackberry jam, the thick tangle of raisins and pecans whisper home. The cousins, the aunts, the uncles, and the rest of us are transported down home to Indian Creek with one rich bite covered in caramel icing.

Cinnamon + cloves = Childhood.

Crystal and Grandaddy Silas in front of Aunt Tannie’s smokehouse in the company of Blondie and Crisco. Photo by Florence Weathers. Courtesy the author

I am always reaching back.

All these years after our grandmother has died, I call Cousin Debra to ask if she remembers the gingerbread sauce. “It had raisins in it,” I say. “It was simple but so good.” Debra calls Aunt Lo, her mother. Aunt Lo is eighty-six. Uncle Bub, her husband and my mother’s brother, is gone. Aunt Lo and Uncle Bub spent the early years of their marriage living with my grandparents.

Aunt Lo remembers. She says:

1 cup of sugar, 1⁄4 cup of butter, 2 cups of water, 1 tablespoon of cornstarch, 2 teaspoons of vanilla. Raisins to taste.

When Debra calls back to tell me the recipe, I don’t allow her to tell me how to mix the ingredients. I want the muscle memory in my body to guide me back across the back roads of Kentucky to Indian Creek into the screen door of our grandmother’s kitchen. I can feel it when I catch the right rhythm, and our grandmother is seemingly there in the flesh.

Granny stirs.

I stir.

We let the sauce simmer until it is thick.

The apparition of my grandmother lingers awhile before it disappears.

I slice a block of gingerbread into a ceramic bowl, spoon on the sauce, taste Indian Creek in my mouth, remember.

Granny Christine’s Jam Cake

This old-fashioned spice cake was the star at Christmas gatherings on the creek. My grandmother baked it a few days before the holiday, and aromas of cloves and cinnamon would fill the entire house. One of the things I’ve always loved about this cake is that while it is sweet, it’s not cloyingly so. The blackberry jam gives it sweetness and also an undernote of tang that makes it a pleasant alternative to any other cake, boxed or homemade. The icing provides all the sweetness you need. You must be ready to spread the warm icing on the cake right after you make it, because it seizes up as it cools.

Serves 12 to 16; makes one 10-inch cake

For the cake

1 1⁄2 cups (3 sticks) salted butter, at room temperature

2 cups granulated sugar

6 large eggs, at room temperature 1 cup buttermilk

1 teaspoon baking soda

1 cup raisins (5 1⁄2 ounces)

For the icing

8 tablespoons (1 stick) salted butter

2 packed cups light brown sugar (about 15 ounces)

1 cup pecan halves (3 1⁄2 ounces) 2 cups all-purpose flour

1 teaspoon ground cloves

1 teaspoon ground cinnamon

1 cup blackberry jam

1 cup peach preserves

1⁄2 cup evaporated milk

3 1⁄2 to 4 cups confectioners’ sugar 2 teaspoons vanilla extract

make the cake: Place a rack in the middle position and preheat the oven to 350°F. Use cooking oil spray to grease a 10-inch tube pan.

Combine the butter and granulated sugar in the bowl of a stand mixer fitted with a paddle attachment or in a bowl with a hand mixer. Beat on medium speed 5 to 6 minutes, until light and fluffy. Stop to scrape down the bowl.

On medium-low speed, add the eggs one at a time, letting each one incorporate before adding the next.

Pour the buttermilk into a liquid measuring cup, stir in the baking soda, and let it sit for a minute or two. (The mixture will bubble a bit.) Add that to the mixer bowl.

Combine the raisins and pecans in a small bowl. Dust them with a

little of the flour to lightly coat. Gradually add the remaining flour, the cloves, and cinnamon to the mixer bowl, beating on medium-low speed until no trace of dry ingredients remains. Stop to scrape down the bowl a few times to make sure all the elements are well incorporated. The batter will be thick.

Use a sturdy spoon to stir in the jam and preserves by hand (streaks of them are okay), then add the floured raisins and pecans, stirring gently until well distributed. Spoon the batter into your tube pan, smoothing the surface. Place the pan on a baking sheet and bake on the middle rack for about 1 hour 45 minutes, turning the pan from front to back halfway through. Cover the pan with foil if the cake seems to be getting too dark. A tester inserted into the cake should come out clean and the top should be mahogany brown, with a few cracks, when it’s done.

Let the cake rest in its pan for 20 to 30 minutes, then dislodge and place it on a wire rack to cool completely, which can take a few hours.

make the icing: Melt the butter in a large saucepan over low heat. Stir in the brown sugar until well combined, then pour in the evaporated milk and stir to incorporate. Raise the heat to medium-high, stirring until it starts to bubble. Continue to cook at a vigorous bubble without stirring for 3 to 5 minutes, until the mass looks like it’s beginning to pull away from the sides of the pan. Its temperature should register 235°F on a digital or candy thermometer. Remove the pan from the heat.

(Alternatively, you can test the mixture by dropping some of it into a cup of cold water. You should be able to roll that caramel into a soft ball, aka the “soft ball stage.”)

Once the caramel is at the right temperature, use a whisk to gradually blend in 3 1⁄2 cups of the confectioners’ sugar, adding more as needed to form a spreadable and lump-free icing. Whisk in the vanilla.

While the icing is still warm, spread it on the cake. Let the iced cake sit until the caramel icing has set.

Photos by Kelly Marshall

A Mess o’ Meatless Greens

Ask anybody in my family and they will say, “There ain’t nothing like a mess o’ greens.” My grandmother would more often than not cook a combination of them: mustard, turnip, and kale. She would throw in some wild greens, too, when she had them on hand.

These are not the ham hock or fatback greens of my childhood. Yet they are just as satisfying and perhaps a bit more healthful—it ain’t my place to say. Making a good pot of greens calls for careful seasoning and the right combination of oil and cooking method. I like my greens with a little heft in them now, but certainly not like the raw greens I’m often served in restaurants, especially in the North. Collards were not the greens of choice up on the creek, but they can be used here. The sautéed method will give you a nice wilted, softened mess of greens that makes a tasty side dish, but you can also achieve the old-fashioned pot likker with vegetable broth as the recipe below calls for.

Serves 4 to 6

1 1⁄2 to 2 pounds kale, turnip, and/or mustard greens

3 tablespoons vegetable oil

1 large onion, chopped

3 garlic cloves, minced

1 teaspoon table salt, plus more as needed

4 cups (1 quart) vegetable broth, homemade or store-bought (32 ounces; you might not need it all)

Freshly ground black pepper

To prep your greens, first strip the leaves from their stalks. (This includes any pre-chopped greens, which are often full of stalks.) Discard or save them for another use; stalks are edible but are not used in this recipe.

Rinse the leaves well in cold water, even if they’re bagged and prewashed, discarding any discolored ones. (There is nothing worse than sandy greens, and I’ve had many in fancy restaurants, but we won’t dwell on that.) Stack and roll the leaves, then cut them into 1-inch-wide ribbons. Or if you are fond of the tearing method, tear bits of leaves apart instead of cutting.

Heat the oil in a large pot over medium heat. Stir in the onion and garlic. Cook for 6 to 8 minutes, stirring often, until the onion is translucent. Season with the salt.

Add your ribbons (or torn leaves) of greens to the pot a handful at a time. As they wilt down, add just enough of the broth to keep the greens from scorching. Add a little more liquid each time as they cook down (they should not be completely submerged, however). Cook the greens, uncovered, for 5 to 10 minutes, until they are tender but not mushy. Taste and season with more salt if necessary and/or pepper.

Serve hot, with some of their pot likker.

From Praisesong for the Kitchen Ghosts: Stories and Recipes from Five Generations of Black Country Cooks by Crystal Wilkinson. Copyright © 2024 by Crystal Wilkinson. Photographs copyright © 2024 by Kelly Marshall. Published in the United States by Clarkson Potter/Publishers, an imprint of the Crown Publishing Group, a division of Penguin Random House, LLC.

This excerpt was published with support from The Julia Child Foundation for Gastronomy and the Culinary Arts.