At a memorial for Tyre Nichols, a portrait his mother described as “The one I want y'all to remember.” Photo by Andrea Morales for MLK50

Tyre Nichols Had a Beautiful Life

A Memphis-born writer reflects on his spirit, his gruesome death, his family, and the burning left in the rest of us

By Zandria F. Robinson

This story is a co-publication with MLK50: Justice Through Journalism, a nonprofit news outlet based in Memphis with the mission to report on the intersection of poverty, power and policy, and to bear witness to movement making and lived experiences. “We hope this story bears witness to not only Tyre Nichols's life but the experiences of Black and working class Memphians affected by the city's history of problematic policing,” MLK50 says. “We ask that after you read it, you join us in reimagining public safety by asking yourself, ‘What makes you feel safe?’”

“See how this official murder out of hundreds marked the difference ...?”

—Toni Morrison, Paradise

There is a hummingbird with a shock of red in Keyana Dixon’s backyard. A mother of three, social worker and gardener, Tyre Nichols’s eldest sibling (and at eleven years his senior, his second mom) has returned to nature to be with the sun. Along with therapy, keeping five journals, and launching a foundation in her brother’s honor to support children’s artistic expression, time in nature is part of her ritual for coping with what persists brazenly in its unimaginability. The hummingbird first struts in flight, to and fro, some feet from her, to get her attention, she says. The next day, it returns, dancing nearer. And then after that, it’s all up in her face, flittering, flapping. “Damn, that’s annoying,” she huffs to herself, swatting. The hummingbird takes leave, and a gentle knowing descends, like the white feather that fell on her face from nowhere the other day. Keyana allows herself a smile at this particular kind of irksome thing, gliding over pale blue air. Like a baby brother.

“I miss him so much,” she says. “I be looking at the phone to see if he gone ask me for $20.” Keyana’s eyes fly quickly to the right, then land center.

“But he don’t.”

In the year since Tyre DeAndre Nichols joined the ancestors on the other side of time, something raw and familiar has been burning in Memphis. His death, a lynching committed by a mob of local police, was a storm that rearranged all our insides, hauling off parts of us never inventoried since the assassination of Dr. Martin Luther King Jr. Too exhausted to look for them good while simultaneously keeping a roof above and the lights on, we, too, have taken vigorously to touching and agreeing with the day and its dwindling light. Each sunrise, we move forward with those stolen parts now hissing, sometimes striking, at our heels, as we grasp for the shine in things. Tyre’s family is now conscripted onto the grisly and ever-growing rolls of those who have lost a family member to police violence. The family survives and persists, beautiful and pained, looking like our Mom, our Pops, our two middle brothers, our big sister, like our aunties and uncles and cousins and everybody we ever knew. Like all who experience the shock of death, families thrust on this uniquely American roll learn in a lightning flash that nothing and no one, no Lazarus-raising Jesus, will come forward to bring their baby back. No do-over of a moment, no alternate route, will emerge. Instead, from under seven seas of grief and fiery pain, they demand what they can, and what they feel inclined and empowered to, of what the community, city and nation owe them: remembrance, support, acknowledgement, firings, convictions, accountability, legislation, reform, change, retribution, punishment, restitution, respair, reparation, eyes, and teeth.

The script for this episode of “The Land of the Free,” one in a never-ending season of police violence, community response, counter-community response, and community response mitigation, is the same and different. Police lie as they do. But surveillance tape from the police’s blue eye in the sky reveals the equal ease and viciousness of their lies. The tape is released relatively quickly, within days, not months, edited but not squashed or disappeared, an opportunity to make an example, perhaps. We know what they say about a broken clock. The surveillance revelation and the hinted heinousness of the video’s contents halt the normal media-powered police propaganda machine, the one that calls victims everything but a child of God to justify their killing to the public.

Then, the officers are mostly Black. To the uninformed, the usual racial motive of Black victim/white officer is absent. The rest of us who live in the city and our bodies, of course, understand that Black officers—some former athletes failed by an injury or general lack of next-level talent, others veterans failed by the government, most coveting the gang membership that their general cone-ness denied them in school—are amongst the most fervent missionaries of anti-Black violence. What else is different here is that perhaps as a consequence of their Blackness, the officers are quickly fired and charged. This back-handed justice stings and turns out not to be the consolation the district attorney’s office imagines, but if we must choose sides, we choose ourselves. A white officer who uses his stun gun during the encounter is fired as collateral damage for his proximity to Blackness but is not charged, as a privilege of his whiteness.

The Black woman police chief who birthed and empowered this particular unit reads a script prefacing the video, condemning its contents, distancing herself from the officers and implicitly running the “bad apples” play, responding quickly and in seemingly compliant ways to public and family demands, talking out of both sides of her mouth. Though she has overseen such a unit, also disbanded, at a previous job in Atlanta. Though she was demoted because of the unit’s actions and later fired for a separate incident from the Atlanta police force and subsequently reinstated, she is still employed. Memphis’s then lame-duck mayor, who ran a Willie Horton-style crime ad in his initial campaign and spent his terms violating consent decrees and surveilling activists and journalists, kicks the can on firing her. The city’s mayor-elect, the developer’s choice, who earned fewer votes than the number of people who work at FedEx, garnering some 23,552 votes out of some 85,000 votes cast, announces he will retain her.

When we see Benjamin Crump, the experienced national lawyer for the families of people killed during police encounters, appear in front of the microphone with the parents of the slain with his own preface to the video, we feel something familiar and sinking and burning again. We mutter in unison: “mmph, this finna be bad.”

Throughout the whole episode, as details of Tyre’s beautiful life and gruesome death became public, and even when the edited video of police beating him was released, and even still when the public saw the photo taken of his swollen face in the hospital, there were no “riots.” The city didn’t burn, at least outwardly, as onlookers expected. Perhaps it was because there were enough plot twists, firings and swift actions, rather than the typical doubling down and obfuscation, to quell the uproar. Maybe it was because Tyre’s mother went on national television and asked us not to tear up our city.

I wonder more about the burning in us, in Black city Memphis. About the fire this time. What it has destroyed and what we will seed if and when it clears. We are okay, we say, but I am curious about the parts of us that leapt into the streets to escape its hot theft, the parts that roam. They aren’t on the television news, but they are in our grapevines. The news we pass from lip to ear in the grocery store and the beauty chair. I see those parts of us, how they dance their red steps in pursuit of us all. We’re as happy and as sad and as rageful and as joyful as we’ve ever been.

Keyana Dixon (left) stands with her siblings Jamal Dupree (center) and Michael Cutrer at the one-year memorial for their baby brother Tyre on Sunday in Hickory Hill. Photo by Andrea Morales for MLK50

“God loved the way humans loved one another, loved the way humans loved themselves; loved the genius on the cross who managed to do both and die knowing it.”

—Toni Morrison, Paradise

Our ancestor Tyre DeAndre Nichols loved everybody and every sunset. Son of the ocean, of Sacramento, of California lineage, Tyre was the striving spirit of Memphis, its quiet places, its landscape, and its river. He was the last of four that came to earth through Oakland’s daughter, Mama RowVaughn Wells, and he was the only one born in Sacramento, at Kaiser, a sacred June Gemini containing two worlds. Mama RowVaughn’s was the house on the dead-end street between an overpass and court where all the neighborhood kids came to play. The siblings—Keyana, Michael, Jamal and Tyre—all had a matching neighbor of their own age to be a companion and mirror. Tyre, the good kid, maad city, skated past the gang colors into his own lane, an individual belonging wholly to himself.

See Ty. See Ty and his friend Bird, riding and riding and riding their bikes. See Ty at six on his skateboard, riding and riding and riding. See Ty’s wheels bunka bunka bunka bunka swoosh swoosh on the asphalt. See Ty conjuring something out of paper. What is Ty making? See Ty grow. Ty is making a world.

Open, loving, free-spirited, curious, striving, whimsical, hilarious, sensitive, and creative, Tyre arrived in Memphis in early 2020 for that restorative dose of Mom-love one needs in his late twenties, especially at the start of that make-or-break rite of passage to adulthood, the Saturn return. Mama RowVaughn had relocated to Memphis in the late aughts, she and Pops Rodney had married. And together, the Wells had made a life and a cocoon that their grown youngest could come to for a rest and a reset. Some things were different, and some were the same. Tyre was a new daddy, and with that came a sharpened focus, an intention and a determination to create lasting stability for himself and his son. He was still fly in the Vans shoes and caps, rolling on the skateboard, quickly finding the vibrant skate community in Memphis. Diagnosed as a teenager with Crohn's disease, a debilitating autoimmune disorder and disability, Mama RowVaughn was still fussing with him about his diet, which for the longest had consisted mainly of chicken nuggets.

The pandemic sat Tyre down just like the rest of us who survived, and he told Keyana that he liked it in Memphis. He had met some nice people, and compared to the soaring prices in California, everything was cheaper. Besides, she told him, he’d have to be ready to hold down three jobs and a side hustle if he came back. So he stayed in Memphis, taking a job at FedEx, where he was deeply beloved for his magnetic quirk, his California vibe, his skater ease, his conviction, his float. This was also the case at the East Memphis Starbucks, which he loved almost as much as chicken nuggets. There, he entered a crew of diverse regulars, mirrors from different mothers, chatting about the thises and thats of things. “Real surface-level talk,” says Nate Spates Jr., a medical sales rep and crew regular. “But it was a feeling,” that unquantifiable quality of good energy that Tyre had that touched everyone he encountered.

Acceptance wasn’t always so easily won for Tyre, from himself or others. Hurting ass, hating ass kids inflicted wounds on him that his family addressed with constant ringing affirmation of their baby boy. He was teased for skateboarding, seen as a white folks’ thing. He was teased for his looks, his richly hued dark skin. For being artsy and plugged into the unseen world around him.

Ever the first-born and only girl, Keyana wasn’t going to let the baby brother that she had dressed, bathed, and taught about the world not understand his beauty, the power of his singularness. Tyre sprouted up lanky in a blink, all of a sudden every bit of six feet three inches. In those confusing adolescent years when everyone told him what he should and couldn’t be, he came home crying to Keyana one day, the weight of other folks’ expectations on his thin frame. She held space for his pain and encouraged him to hold fast to skateboarding, his own freeing and defining thing. “You can only be great at being you,” she told him. This advice Tyre sheltered in his marrow, a mantra that strengthened him in all ways and always, from the Pacific to the Mississippi.

In his bones, too, was a radical commitment to justice and remembrance. Across his social media, where people have come to get a posthumous glimpse of his divine otherworldliness and to lament his death, he stayed wonderfully woke: acknowledging Pride month, encouraging remembrance of Indigenous displacement and genocide, advocating for Black lives, and celebrating Black women. In a picture with Mama RowVaughn, Tyre wears a “Black Men Deserve to Grow Old” hoodie from Jermia “Mia Jaye” Jerdine’s campaign to raise awareness around violence, first in the wake of her brother’s death and then in that of her children’s father, the rapper Adolph “Young Dolph” Thornton Jr. His arm around his mother, his face flashes a kind of determined ease, a satisfaction. In that hoodie, he looks like he belongs to Memphis in a real tender way.

Memphis always transforms the weary believer, the misfit, the flesh that knows it contains big spirit, the big spirit pulsing against its fleshy container. And they, in turn, bend the city into spectacular, delicious shapes. Tyre was on a journey here in Memphis, a movement within and toward himself, one at once so familiarly American, so definingly millennial and so very Memphis that its horrifying end echoes endlessly over this smoky quartz air. Tyre changed the place in the flesh and brought a storm in spirit that shifted us, set something to burning. He didn’t make it to the other side of his Saturn return. The police beat him as the full moon and their blue eye watched. Only the blue eye flinched. As the moon waned, so did Tyre, deprived of the power of his breath. He hadn’t even gotten in a good decade of knowing he was handsome. And he certainly would have spent his thirties being hella, as the folks from California say, great at being himself.

They have stolen our capacity to see what came next. But we still witness, speculate about and imagine what it would have been here on earth. And when he throws open the red curtain, we peek into the parallel world where Tyre skates through his fantastic afterlife.

Folks at a memorial for Tyre last January at Tobey Park skate park watch the action. Photo by Andrea Morales for MLK50

“How can they hold it together … this hard-won heaven defined only by the absence of the unsaved, the unworthy and the strange? Who will protect them from their leaders?”

—Toni Morrison, Paradise

In the era of social media and the ubiquitous personal camera, we all seemingly have the power to turn the lens of truth on the powerful in the interest of justice. And yet despite this capacity to witness and publicize, it is well established that the police can and will harm anyone, anywhere, at any time, for anything. Police disproportionately harm people racialized as Black, Indigenous and Latino, even when watched by their own cameras. One of the solutions, goes some half-thinking, is more Black officers, more officers of color. Thus, a majority Black city with a significantly Black police force is thought to be exemplary of the standards and possibilities of good policing since Black people on both sides of the thin blue line are thought to share the same culture and aims. This argument ignores the basic purpose of policing, which, beyond its stated function to serve and protect communities, is to enforce the power of the ruling class over the people, protecting the order of things by all manner of force. My baby boomer Mama tells me, “When them people put on a uniform, it don’t matter what color they are.”

Police are human, and they know that we are human, even as they shoot us in the back and beat us about the head and body. It is softer on our psyches for us to believe that, since slavery, people in power’s main failure has been in their capacity to see us as human. Because then all we must do to stop their violence is to prove to them we are human, to humanize ourselves. To dance and sing and love and dress well and get married and speak proper English. But the reality is that they have always known we are human—what they lack is respect for humanity, ours and their own, which is fueled by a culture of ravenous greed. And their lack of respect for humanity, coupled with leadership’s lack of respect for humanity, everywhere fills our communities with holes, breaks, and blood.

Despite a robust youth-led movement in Memphis to redirect funds from the police to the community, few of the elders believe in abolishing or defunding the police. Still, no one in these parts believes the old threadbare lie of reform. Whether we can bear the wet heat of this hot August truth—that the criminal justice system is working exactly how it is designed to work and how it has always worked, as a mechanism of race and class subjugation—is another matter. The fleshy fact remains that a killing of this sort in Memphis, whether it is Dr. Martin Luther King Jr. on the balcony of the Lorraine Motel Downtown or Tyre Nichols on a quiet block in southeast Memphis, is always a terrorizing message to the city’s largely Black working classes to stay in their place.

A high-profile police killing, this one occurring before our grandmothers had the chance to change their wall calendars good, tends to yield a spike in crime as it is traditionally reported. The city’s leadership consistently refuses to truly address the city’s enduring equity issues, caused in no small part by corporations that pay low wages and few taxes and underfunded schools, and the fallout thereof. They point, as always, to the poor choices of the working classes and the lack of parental involvement rather than accounting for how the city needs the working classes to remain subjugated to support the urban development growth machine model of city survival. The city’s mainstream media has been breathlessly reporting the increase in crime this year over last year, but, of course, has done far less reporting on the increase in rent and groceries.

The community keeps an alternate set of statistics of the crimes of absent healthcare infrastructure, underfunded schools, of police writing tickets but not stopping gangs who everyone, including them, knows on first-name, street-name, and last-name basis. We tally the rise of depression and anxiety and complex PTSD in young people. Of the hush-hush speculation of whose death was really a suicide because no mouth in the family will spill the cause. Of domestic violence. On who got put out and had to double up. On who had to get a third job and started taking something they shouldn’t to stay awake or keep the pain at bay. Of whose auntie is in the hospital. On how much they charging for apartments now. Of who heart gave out way before its expiration date. Of who misplaced they mind in the middle of Lamar and who tried to help them find it. Of what new shit they building that isn’t for us but that we gone make ours anyway. Of kids getting hold to the new drugs. Of our grief outside of our bodies, walking down the street loud and banging.

“It’s like misplaced aggression,” says Nate, Tyre’s friend from Starbucks. “It’s not gone come out here, but it’ll come out over here. You can’t keep suppressing it. The city is just upset.”

Organizer Jayanni Webster ties chronically low wages and increasing rents to a growing level of isolation, in part seeded by COVID, but moreover an outcome of a tenuously tethered economic reality. “Everyone is going through the exact same thing, and no one is speaking of it. And no public leader is speaking to it. The only way they speak to it is to name crime. Collectively, everyone is concerned about crime because there is real desperation.”

There is a proliferation of nonprofit organizations to address poverty. Yet, unsurprisingly, poverty persists at near the rates they were when King was killed. As is the case in most parts of the country, the working classes in Memphis subsidize and make possible the paychecks and lifestyles of an entire managerial class, from nonprofit workers to social workers to the police. What the managerial class is underpaid in salaries, they subsidize with the righteous compensation of serving the public (and telling their friends on the East and West Coast that they’re serving the public) in one of the poorest, Blackest, most Old South cities in the country.

In the crudest mathematics, Memphis is constitutive of two coexisting, generally parallel but sometimes intersecting sites: one, a Black city, the other, a white town. The white town might be said to be comprised of the wealthy and the politicians who serve them, city boosters, mainstream media outlets, nonprofits, philanthropy organizations, wealthy donors, anything with “leadership” or “new” in the title, poverty pimps, police, people who commodify Black language to describe life in the city, developers, and those who use their residency in the city to claim authenticity and “grit” over their counterparts in richer cities.

Working-class whites labor in the shadows of the white town proper. Their numbers were once dwindling, with white poverty in Memphis appearing to decline at one point in the aughts. While some of this shift came from the exodus of poorer whites to surrounding counties, it was mostly white middle-class growth that contributed to the decline of poor whites in the city’s overall white population. In the ongoing wake of COVID and the co-occurring collapse of many smaller white towns in the surrounding area, Memphis’s white town is primed to attract working class white Gen Z and millennial population growth. Though parallel, the power of the white town is built on top of the exploited Black city and on top of the ravaged Indigenous city.

The Black city might be said to be composed of laborers of all sorts, mostly Black and Latino, in the manufacturing, warehouse, health care and service economies, who make the city go. The ladies at the DMV, the FedEx hub workers, the sanitation workers, the gold-toothed cashiers at Krystals, the checkers at Kroger, the CNAs at the care homes. The Black city is on a connected map of Black cities across the region and country, including Houston, Jackson, Mississippi, the Mississippi Delta, New Orleans, Atlanta, and Chicago. Within any city is a collection of neighborhoods, sites of the daily round, labor, leisure, and pleasure. The exploitation of the Black city, its legions of laborers in global multinational corporations, keeps prices relatively affordable for the middle classes in the white town and renders the political system unchanging in its power arrangements. Cheap labor and tax cuts support the global economy and Western imperialism. Black city Memphis carries the world on its back, under its fingernails, in its trucks, in its weary heart.

Now full-throated in its rampant gentrification phase, Memphis continues to tout its cheap and captive labor force to companies while advertising its cheaper cost of living to the upwardly mobile and the middle classes, yuppies and buppies, priced out of more expensive cities. Black leadership aligns with white development interests to build a city for the upper classes. In this era where everyone across class is representing their city like only rappers and football fanatics once did, the performance of grit and grind has become a marker of cool and authenticity in the increasingly undifferentiated though multiracial millennial middle and upper classes. Actual grit and grind, the result of the desperation caused by its continued devaluation of Black life and labor, is not so popular and is heavily and literally policed.

In Memphis, our ancestor Tyre joined one of the largest and most exploited Black working classes in any U.S. city at one of the global headquarters of this exploitation, FedEx. And yet, starting anew in this river city, he brought a whimsy and pride to the work that was so distinctly him, and so familiarly late twenties. The work was a means, as it is for so many people, for him to get where he was going. He had told his mother he was going to be famous.

When police finally returned Tyre’s car to Mama RowVaughn, inside was his work vest. On the vest was a name tag. “It was really neatly done,” Keyana says. “He had typed and printed it.” The Box Manager, it read. He was an assembler of things, giver of dimension to something flat, a deft manager of various containers, all of us different people he encountered with our different energies. Even in the most uniform and oppressive of places, Tyre adorned himself in shine, this time placing his spirit work on his chest.

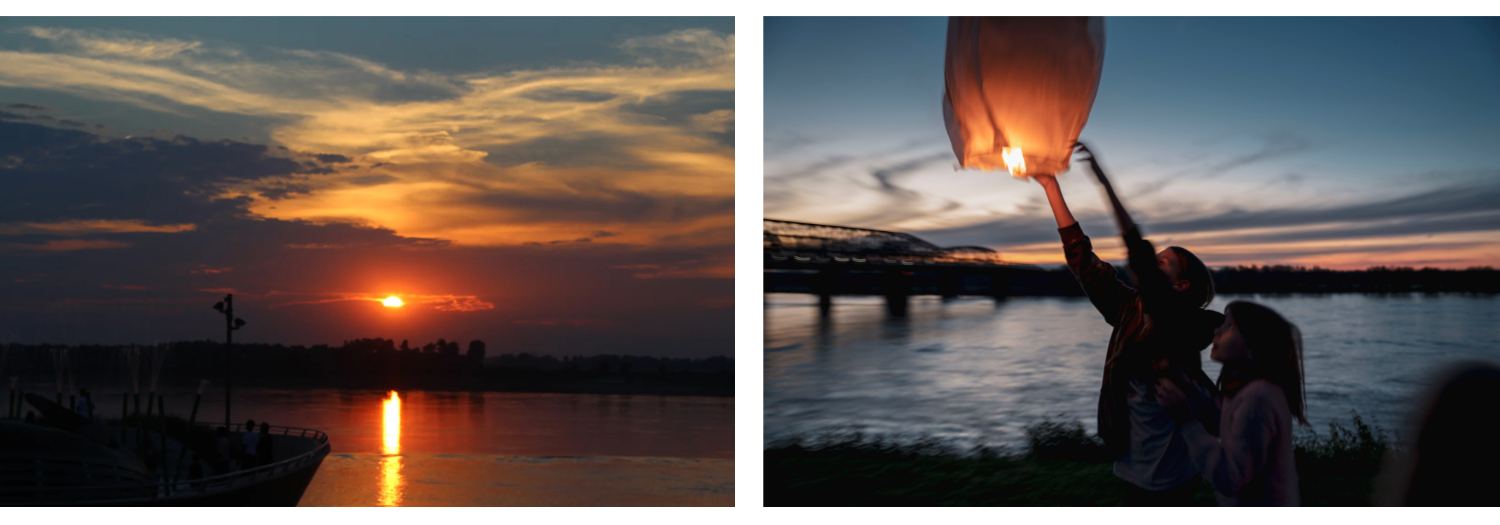

Left: Photo by Tyre Nichols; Right: A lantern at the April memorial event for Tyre Nichols floats over the Mississippi River, photo by Andrea Morales for MLK50

“Rocked as they were by the sight of evil, its snout was familiar to them.”

—Toni Morrison, Paradise

Keyana is recounting to me that evening of the year’s first Friday. It’s early November when we speak, nearly nine months after his killing, but it’s after the end of the world, where time is a boomerang.

“Ty should be home by now.” That’s what Mama RowVaughn told her on the phone that night. The mother and daughter were doing their weekly check in, and Mama RowVaughn was making Tyre’s favorite preparation of chicken—sesame. “And she kept saying, ‘Key, my stomach hurt.’ And I was like, you probably ate something weird. And she kept walking to her window.”

The two got off the phone when the police banged on Mama RowVaughn’s door, pouring all their usual acid lies in her ears. Tyre had been arrested for DUI, they’d said, and they’d had to use a stun gun on him and rough him up a little bit, because he’d been especially strong. Mama RowVaughn called Keyana back, repeating what she’d been told. Both women knew that didn’t sound any kind of right. Still, Keyana was hopeful, reassuring her mother that Tyre would be okay. “Thank God they were Black, because it could have been worse,” she said to her mother.

“I’ll eat these words for the rest of my life,” Keyana tells me.

When she learned three days later that her baby brother—the sibling she was most like, and the one most like her; the baby she bathed and dressed and helped raise, that easygoing spirit, the one whom she’d cheered relentlessly; with whom she’d spend hours on the phone talking—was gone from this world, she lost consciousness, fell down the stairs in her home and injured her nose. She hadn’t gotten to say goodbye.

“He’s always been—and I’m not just saying this—he’s always been very mild-mannered, very respectful, very to himself, very artsy, creative, that’s just who he was. He was the most nonconfrontational person. And for him to die the way he did. That will never sit right with me.” This fact also hunts us, burns in us.

Tyre photographed one of the surveillance boxes Downtown on Beale Street, a vulgar light amid the neon of “Blues City Cafe,” and the white neon figure in the walk sign. The police surveillance cameras, called SkyCop, are all over the city, and sometimes the portable ones, like in the parking lot of a medical district Walgreens, for instance, blast classical music. There is a great disdain for them, as they are perceived as yet another waste of city funds, this one with a side of repression that does not, in fact, deter crime. We have come to live with them as a sign of police disdain for us. “What’s the sense of watching each other in this way,” the movement photographer and MLK50: Justice Through Journalism visuals editor Andrea Morales asks, “if we’re not seeing each other?” I imagine that in that moment, on some evening on Beale, Tyre the artist has photographed the MPD box to contrast the types of light in this world, the kinds of sight, what it means to be visible and to whom. Camera to camera, Tyre’s eye to the police state’s eye, the photo also seems to say, “I see you, too.”

As police attack him, Tyre strains and calls for his mother, who is growing increasingly worried, repeatedly checking the window, her gut wringing itself. It has not yet become clear what it is trying to tell her.

“Ty needs to hurry up,” Mama RowVaughn says. She ain’t making this chicken for nothing.

Pepper sprayed but temporarily back on his feet and escaping the police, who give chase and threats, Tyre dashes for home, making it just around the corner, until the police, extra mad because they are winded, catch him, ground him, finish him. With each blow, they finish themselves, too, along with seven generations of their bloodlines, backward and forward.

“He probably stopped at Starbucks,” Keyana offers.

There above Tyre in the sky are two lights: the full moon and the surveillance box. Gravity tackles the moon, keeps it from crashing down on the scene. The box first determines to close its eye, to look away, going black. Then it opens, turns back on. In a silent duty of recognition of the spirit with the camera, the blue light bears witness.

Knocked from his earthly home, Tyre skated to his home on the other side of time. He was to have thirty turns around the sun in June.

Keyana arrived in Memphis after Tyre’s death to find her mother catatonic, eyes wide, unable to move or speak, a state she stayed in for three days. “That hurt me,” she says. From the raw space of her grief and shock, she demanded there be more, more something, more action from the people, for somebody to do something. “And that’s what made me go marching. Where we going? What we doing? Because she can’t talk. She doesn’t have a voice.”

She found herself with a scant dozen people marching to the police station as people were preparing to honor the MLK holiday. In the days and weeks to come, as the family was besieged by not only irreconcilable horror and grief but also by the greedy public and media storm eager for a bite of their pain—“They wanna be attached to your tragedy for their own personal gain,” Keyana says declaratively—their roles in this new, ugly script took shape. They have perhaps unintentionally divvied up their public roles, though each feels, amongst other things, the grief, rage, anger, guilt, vengeance, and justice strivings that come with this brutal territory. Like the mothers of slain sons before her, Mama RowVaughn, with Pops Rodney ever at her side, bears the glare of the camera, of telling the story of her son’s life, of his last moments, and of advocating for justice locally and federally. Like eldest daughters do, especially ones that helped raise and dote on their baby brothers, Keyana has become the emotional repository, the shadow to her mother’s necessary public strength. Jamal was out front like the big brother he is, on CNN telling Don Lemon, the Bay Area all in his mouth, “I hope they meet the same fate as my brother. That’s just how I feel,” containing the feelings of guilt and grief and vengeance that he wasn’t there to protect Tyre. And there’s Michael, the brother who looks so much like Tyre as to be a premonition, a precursor, a preface, an announcement of his brother’s birth. He can’t with the interviews. The rage is there. Now, when he comes to court, he will wear his brother’s face, and he will be a haunting.

To be sure there has been, as there always is, movement and momentum and moments of protest in Memphis. Organizer Amber Sherman, who came of age in the neighborhood where Tyre was killed, has been disheartened and enraged by the palpable disinvestment in and antagonism towards the city’s Black citizens and neighborhoods. She’s been a key and vocal advocate for change in the wake of Tyre’s killing, building sustained and creative organizing practices for the moment and the long struggle. For Amber, the citywide ordinances, including one to halt pretextual police stops and another requiring data transparency for traffic stops—ignored by the former mayor, newly enforced by the present one—were significant successes, accountability is demonstratively absent. Unsurprising for a city leadership that seems historically desperate to be best friends with the Department of Justice, but grating nonetheless. Pretextual stops continue, and the deadline for the police’s data report has come and gone, with inquiries after the report unanswered. “We’re having to continue to organize for accountability because they’re playing in our faces. Everybody’s in contempt.”

The burning, the longstanding grief, and the ongoing everyday violence of repression by police, corporations and condescending leadership inhibit some of the most expressive kinds of political action, a wing-clipping weight on everybody. “We have a governmental system that is unwilling to do what’s actually necessary to make it where citizens are okay,” Amber says. “[City leadership] knows exactly what would help us. They are purposely choosing not to do that because if we get any kind of economic power, that makes us in more control than them. If I’m able to work a job where I don’t have to be at work from 6 a.m. to 9 p.m., and I can go to city council meetings, and I can send emails to my elected officials, and I can be able to hold them accountable? Other than just the random real estate people who come every meeting? Then what kind of environment does that create?”

“Most folks are trying to get by,” Jayanni observes. “They don’t necessarily have time to stop their lives to respond. And not because they didn’t want to. Because every household was talking about it. At the grocery store. At church. Folks were angry. But were they not going to clock in at Nike or Williams Sonoma so they can go Downtown to protest? No. The fact that people don’t have the opportunity to have political expression beyond going to the voting booth and upholding whoever wants to govern next benefits the structure that has always been here.”

Still, we press on, now on a different timeline, A.T., After Tyre. “We have as much time as we need,” Amber says, unyoking herself and us from the urgency capitalism insists upon, even in organizing. “If we don’t get what we want the first time, we just try again. We’re just gone try again. I’m still here. And other people are still alive. I still have breath in my body, and I’m still able to move around, so I can still try again.”

There is most certainly a different, forever kind of fire this time in the people. There is a bristling disdain for the police chief, some of it prefiguring Tyre’s killing, that cannot all be chalked up to the usual anti-Black misogyny that plagues women in leadership. Newly-elected mayor Paul Young sent an email to his supporters saying his decision to retain the chief had been met with “mixed responses,” a phrase parroted by a Local Memphis ABC affiliate segment—a segment that proceeded to then only show one, positive, review. Still, in the barber and beauty chairs, at the church, at the bar, somebody knows somebody who has had a run-in with this particular mob of SCORPION officers, giving grotesque meaning to a common refrain here, “Memphis is a small town.”

For many, the officers’ masks have been an especially aggravating indignity, a last fiery straw. “Every time I see they face I feel a certain way,” Keyana says. “The things I’ve been trying to press down, they come back up. The first time I saw the officers in court, and I saw how big they were. That blew my mind. They wouldn’t look at us. They all wore masks as a defense mechanism. I just know that.”

Even the measured Nate mentions the masks. “I think the most cowardice thing I see is when they show up with these huge face masks on. Now you worried about germs. It’s like what are you hiding from now? It just irritates me to no end.”

That first time in court, Keyana breaks out in a severe rash all over, her body reacting violently to the stress of the moment, the grief, what she’s held in and what can’t be said or shouted or screamed or ripped in this court of law. For her, right now, justice is in equal tears. “I want they Mamas to cry like my Mama cried,” she says, her voice a soft red wind.

For Nate, “The officers that murdered Tyre are prisoners of their own existence. Justice is happening right now. Justice is in the air.”

“My worst days are over,” Keyana says of the officers. “Yours are to come.”

We are a city, a people, that believes in God’s plans. We know God is real. We are ring shouters, tambourine players, diviners, wailers, dice rollers, and stompers. We might not say aloud in mixed company, but we know demons are real. We know what one human will do to another human’s flesh without blinking. We can be unforgiving. We are skeptical of systems of power and their capacity for justice. We believe wholeheartedly in God’s vengeance. We pray Psalms 58 every single day.

A memorial for Tyre Nichols sits where his fatal assault ended, on the corner of Castlegate Lane and Bear Creek Cover in Hickory Hill. Photo by Andrea Morales for MLK50

“Real wonder, however, lay in the amazing shapes and substances God’s grace took: gospel in times of persecution; the exquisite wins of people forbidden to compete; the upright righteousness of those who let no boot hold them down—people who made Job’s patience look like restlessness. Elegance when all around was shabby.”

—Toni Morrison, Paradise

Our ancestor, the son, brother, father, and holy spirit Tyre DeAndre Nichols, taught us how to make a world. We have been making it with every step and breath since they took him from this earth. We know that he was Sacramento’s son, too, of California birth. But it is no small matter for us when a person who loves our city, who finds the light in our city, also becomes an ancestor in our city. Here in Memphis, we people who came up from enslavement and sharecropping, who today toil still in new ways with old rings, have always imagined different futures and carried them glittering to the present. We are exhausted, in mourning, in shock, in pain, in need of replenishment, but also making a life every single day, enough cackling and joy to fill the heavens. And we believe that things can be different. And they will be.

Tyre made landscape to reckon with his interior, wrapped himself in the beauty of this place, in stillness. He was ever in search of the wild turns of color, the light, mirror and shadow that Earth would make as it bowed on one side and prepared to stand on the other each night. He was a whole vibe, as the young people say, a free-spirited, skateboarding, country-music-singing kaleidoscope, carrying himself through the world and loving himself and all of us like God loves us.

Andrea, the movement photographer who has documented the last decade of the spectacular everyday in Memphis, describes Tyre’s art as “unburdened and pure, full of wonder and aware of light,” still in a place of whimsy and exploration that sometimes photographers lose in the technical aspects of the craft. “Maybe he was one of those people that had a prolonged relationship with light.” He was fantastically alive in all the human and God ways. Now, he is ecstatically alive in all the spirit and God ways.

“That was me at twenty-nine,” Nate says of Tyre. “Just working an honest job, trying to do the right thing, trying to enjoy what little bit of happiness I could find anywhere. I loved photography, I loved graphics, I loved music, and I would just go off into the countryside and just turn my music on to get away from the city and relax and decompress.” This was Tyre, out at Shelby Farms Park, dancing with himself to “Footloose,” lithe and beautiful, welcoming new angles of sunset and river and giving them to us in wonder and offering. This was every one of us.

For Keyana, the sun in her yard, the plants and the little signs, like seeing 901 all the time, persist. She keeps several altars for Tyre. The pictures he took at her wedding, where he so deftly captures the otherwise unnoticeable, are now a memorial of his eye, his love, his art, his witness. She is determined that Tyre will live on in the foundation she has begun in his name, which aims to connect kids to their inner lives and their creativity through after-school programs and creative arts scholarships. Part of her aim is to give children cameras to make the world, and, of course, to bring them to skate in the beauty of the expansive park where Tyre found so much solace. “I am focusing on everything that he loved,” she says.

We owe it to ourselves to welcome this powerful transmutation, this powerful channeling of energy, and to support it with all our might, for all of our children here. “He was such a curious kid, and we didn’t have a lot of resources. And there are so many kids in these areas that don’t have the resources or the spark and the confidence to say, ‘This is who I am, and I don’t have to conform to what my neighborhood says or my parents.’ My brother dealt with that, where he felt like he had to be a certain way. And it was me always telling him, ‘No, you don’t.’ And now look. He was himself. And he was great at it.”

“… no better battle to fight, no better place to be than among these outrageously beautiful, flawed, and proud people.”

—Toni Morrison, Paradise

Find Memphis alive with Tyre’s spirit, whish, whish, whish roller skating on Riverside in the gliding summer, sitting in the tall proud grasses at the edge of Shelby Farms, down by the ever-flowing Mississippi, dancing to all the beats, screaming out our lungs at some concert. Find us innovating new checks, making new ways to signify, turning the dozens into thousands. Find us connecting to each other again, so tenderly, witnessing the fire in each other, nurturing what burns, befriending the shadows that haunt. Find us collecting the parts of ourselves thrown from our bodies by this tragedy and reassembling ourselves anew for the march forward. Onward, beautiful strivers who remember everything.

We thank you, Tyre DeAndre Nichols, for coming here to Memphis to make a life for a time. We thank Mama RowVaughn for bringing you into the world, June baby. We thank Sister Keyana, Brother Michael, Brother Jamal, and the second mothers, God siblings, extended family, and everyone who helped you stay great at being you. We thank you for your courage and strength to persist as yourself. We thank you for hugging us, for showering us with your holy energy. We witness your meteor light, and each day we try to hold the world in our eyes the way you did, cradle the city in our sight the way you did. We promise to remember to roll and fly like you did, play games like you did, kick it like you did, go out like you did, stay to ourselves like you did, be respectful like you was, graceful like you was, to speak up like you did, where you finna be at, Ty? Where you at? With every breath, step and move, we sing you, and we remember. We love you because you’re ours. And we will see you on the other side of time.

Thank you for remembering everything.