Mystic Nights

The Making of “Blonde on Blonde” in Nashville, Tennessee

By Sean Wilentz

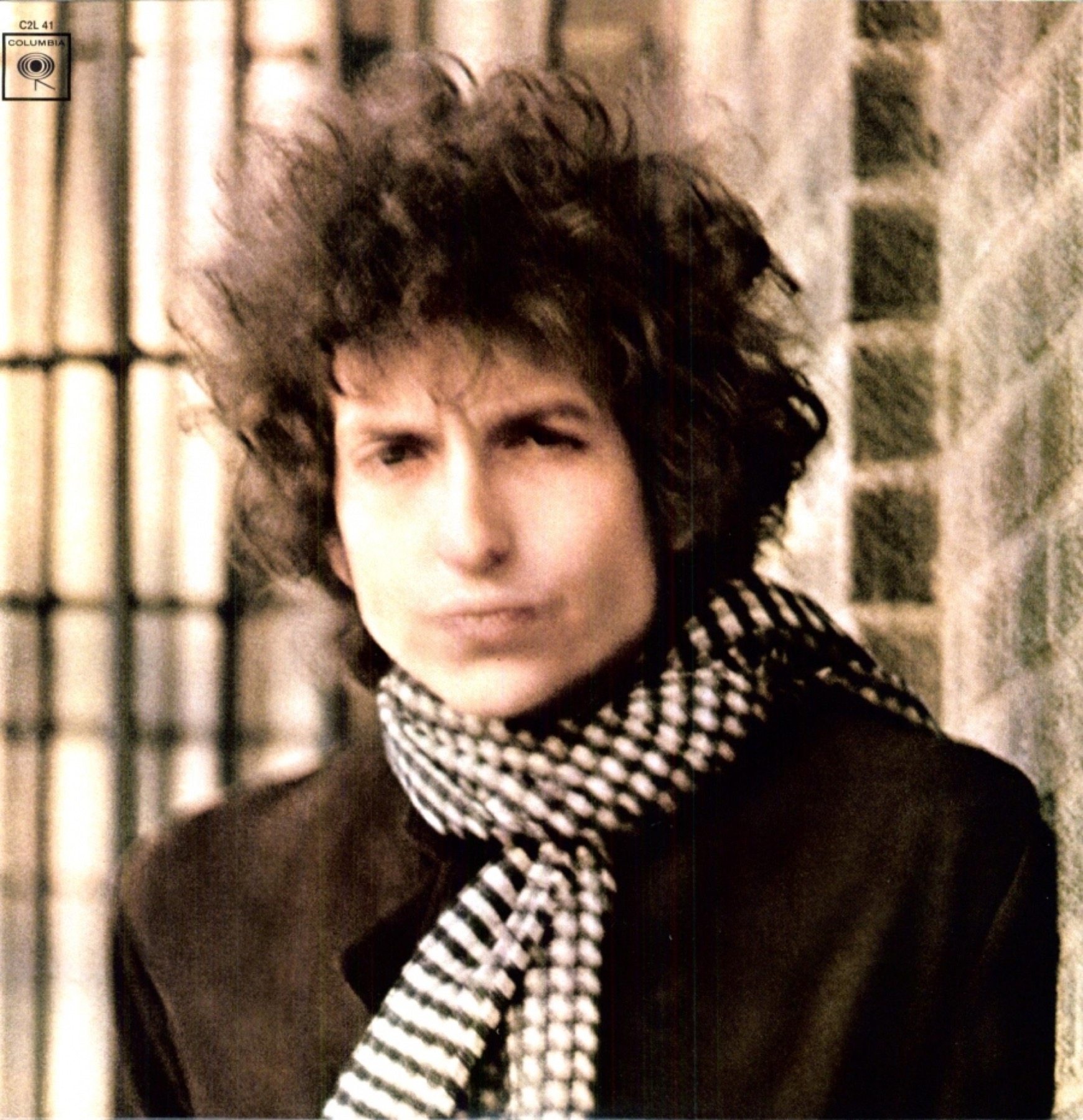

Columbia – C2L 41

A memory from the summer of 1966: Across the Top 40 airwaves, an insistent drum beat led off a strange, new hit song. Some listeners thought the song too explicit, its subject of wild lunacy too coarse, even cruel; several radio-station directors banned it. Despite the controversy over the lyrics about madness and persecution, or more likely because of it, the record shot to No. 3 on the Billboard pop-singles chart. The singer-songwriter likened the song, which really was a rap, to a sick joke. His name was Jerry Samuels, but he billed himself as Napoleon the XIV, performing “They’re Coming to Take Me Away, Ha-Haaa!”

That spring, an equally controversial single, with an eerily similar opening, had quickly hit No. 2; and by summer, “Rainy Day Women #12 & 35” had reappeared as the opening track on the mysterious double album, Blonde on Blonde, by Bob Dylan, who said the song was about “a minority of, you know, cripples and orientals and, uh, you know, and the world in which they live.” Over Coppertone-slicked bodies on Santa Monica Beach and out of secluded make-out spots and shopping-center parking lots and everywhere else American teenagers gathered that summer, it seemed that, the ba-de-de-bum-de-bum announcing Dylan’s hit about getting stoned was blaring from car radios and transistor radios, inevitably followed by the ba-de-de-bum-de-bum announcing Jerry Samuels’s hit about insanity. It would be Samuels’s last big recording; and after July, Dylan would be convalescing from a serious motorcycle crash.

Such were the cultural antinomies of the time, as Bob Dylan crossed over to pop stardom. Blonde on Blonde might well have included a character named Napoleon XIV, and the album sometimes seemed a little crazy, but it was no joke (not even the frivolous “Rainy Day Women”); and it was hardly the work of a madman, pretended or otherwise. At age twenty-four, Dylan, spinning on the edge, had a well-ordered mind and an intense, at times biting, rapport with reality. The songs are rich meditations on desire, frailty, promises, boredom, hurt, envy, connections, missed connections, paranoia, and transcendent beauty—in short, the lures and snares of love, stock themes of rock and pop music, but written with a powerful literary imagination and played out in a 1960s pop netherworld.

Blonde on Blonde borrows from several musical styles, including ’40s Memphis and Chicago blues, turn-of-the-century vintage New Orleans processionals, contemporary pop, and blast-furnace rock & roll. And with every appropriation, Dylan moved closer to a sound of his own. Years later, he famously commended some of the album’s tracks for “that thin, that wild mercury sound,” which he had begun to capture on his previous albumsBringing It All Back Home and Highway 61 Revisited—a sound achieved from whorls of harmonica, organ, and guitar. Dylan’s organist and musical go-between Al Kooper has said that “nobody has ever captured the sound of three A.M. better than that album. Nobody, even Sinatra, gets it as good.” These descriptions are accurate, but neither of them applies to all the songs, nor to all of the sounds in most of the songs. Nor do they offer clues about the album’s origins and evolution—including how its being recorded mostly in the wee, small hours may have contributed to its three A.M. aura.

Reminiscences and scraps of official information have added up to a general story line. During the autumn and winter of 1965–66, after his electric show at the Newport Folk Festival in July and amid a crowded concert schedule, Dylan tried to cut his third album inside of a year at Columbia Records’ Studio A in New York with his newly hired touring band, the Hawks. The results were unsatisfactory. Blonde on Blonde arose from Dylan’s decision to quit New York and record in Nashville with a collection of seasoned country-music session men joined by Al Kooper and the Hawks’ Robbie Robertson.

From the time he began recording regularly with electric instruments, Dylan, his palette enlarged, fixated on reproducing the sounds inside his mind with minimal editing artifice. The making of Blonde on Blonde combined perfectionism with spontaneous improvisation to capture what Dylan heard but could not completely articulate in words. It also involved happenstance, necessity, uncertainty, wrongheaded excess, virtuosity, and retrieval. One of the album’s finest musical performances, maybe its finest, unfolded in New York, not Nashville, perfected by a combo as yet not properly credited. Some of the other standout songs were compact compositions that took shape quickly during the final Nashville sessions. And what has come to be remembered as the musical big bang in Nashville actually grew out of a singular evolution that turned one grand Dylan experiment into something grander.

“That’s Not the Sound”

The first recording date at all connected to Blonde on Blonde took place with the Hawks in New York on October 5, 1965, barely a month after the release of Highway 61 Revisited. Dylan had just performed his half-electric show at Carnegie Hall and in Newark (only his third and fourth concerts ever with the Hawks), and, to his surprise, received a warm response. “Like a Rolling Stone” had hit No. 2 on Billboard over the summer; now, following successful concerts at the Hollywood Bowl, and in Austin and Dallas, the booing furies of Newport and Forest Hills seemed to have receded, at least temporarily. Dylan’s new sound initially went over much better with audiences down South, where rock & roll was born, than in most other places, and so the applause at Carnegie Hall was unexpected. Dylan was also still learning about how to play onstage with a band, and the Hawks were still getting used to playing with him; the kinks would surface inside Studio A.

The Texas-born producer Bob Johnston, a protégé of John Hammond, had overseen the final Highway 61 sessions and was back for Blonde on Blonde. Not surprisingly, Dylan had not written any new material that approached “Like a Rolling Stone” or “Desolation Row.” This first day’s efforts included seven takes of a hipster joke called “Jet Pilot,” and seven of a quasi-parody of the Beatles’ “I Wanna Be Your Man.” The second song improved during the session and had some intriguing lines; shards from the entire day’s work would later reappear on Blonde on Blonde; but the results, maybe intentionally, amounted to musical warm-ups. The date’s bright spot was recording new takes of “Can You Please Crawl Out Your Window?,” a “truth attack” single left over from the Highway 61 sessions.

Over the next two months, Dylan and the Hawks resumed touring—from Toronto, Canada, to Washington, D.C.—and the booing resumed, though not in Memphis. On November 22, Dylan married Sara Lownds. Eight days after the wedding, two days after the Washington concert, and one day before flying off for a West Coast tour, he was back in the studio with the Hawks, minus drummer Levon Helm, who had wearied of playing in a backup band and quit; Bobby Gregg played in his stead. The newlywed now carried with him a masterpiece he had to record right away. “This is called ‘Freeze Out,’” Dylan announced with a note of triumph as the tape started rolling for the first session take.

“Freeze Out” was “Visions of Johanna,” virtually intact, but Dylan was even less certain about how he wanted it played than he was about the title. On the session tape, he and the Hawks change the key and slow the tempo at the start of the second take, if only to hear more closely; “that’s not right,” Dylan interrupts. He speeds things up again—“like that”—and bids Gregg to go to his cowbell, but some more scorching tests are no good either: “That’s not the sound, that’s not it,” he breaks in. “I can’t…that’s not….” Two more broken attempts feature Richard Manuel playing on the harpsichord: “Nah,” Dylan decides, though he keeps the harpsichord in the background. Out of nowhere comes a slower, hair-raising, bar-band rock version. But Dylan doesn’t hear “Freeze Out” that way either, so he quiets things down, inching closer to what will eventually appear on Blonde on Blonde—and it is still not right. Dylan had written an extraordinary song—he would boast of it at a San Francisco press conference a few days later—but had not rendered its sound. Over the coming months, starting in Berkeley, he would perform the song constantly in concert, but in the solo acoustic half of the show. (The first “Visions of Johanna” date did yield, in an evening session, a forceful final take of “Crawl Out Your Window”—but the single’s release, just after Christmas, generated mediocre American sales.)

Dylan became frustrated and angry at the next Blonde on Blonde date, held three weeks into the new year during an extended break from touring. In nine hours of recording, through nineteen listed takes, only one song was attempted, for which Dylan supplied the instantly improvised title, “Just a Little Glass of Water.” Eventually renamed “She’s Your Lover Now,” it’s a lengthy, cinematic vignette of a hurt, confused man lashing out at his ex-girlfriend and her new lover. Nobody expected it would be recorded easily. (Dylan’s manager, Albert Grossman, interjects on the tape, just before the recording starts, that there is a supply of “raw meat for everybody in the band.”) The first take rolls at a stately pace, but Dylan is restless and the day has just begun.

On successive takes, the tempo speeds, then slows a bit, then speeds up again. Dylan tries singing a line in each verse accompanied only by Garth Hudson’s organ, shifting the song’s dynamics, but the idea survives for only two takes. After some false starts, Dylan exclaims, “It’s not right…it’s not right,” and soon he despairs, “No, fuck it, I’m losing the whole fucking song.” He again changes tempos and fiddles with some chords and periodically scolds himself as well as the band: “I don’t give a fuck if it’s good or not, just play it together…you don’t have to play anything fancy or nothing, just . . . just together.” A strong, nearly complete version ensues, but Dylan flubs the last verse. “I can’t hear the song anymore,” he finally confesses. He wants the song back, so he plays it alone, slowly, on his tack piano, and nails every verse. He reacts to his own performance with a little “huh” that could have been registering puzzlement or rediscovery. But Dylan would end up discarding “She’s Your Lover Now,” just as he would abandon a later, interesting take of an older song, “I’ll Keep It with Mine.”

For better or worse, Dylan had become used to honing his songs and then working quickly in the studio, even when he played with sidemen. He had finished Bringing It All Back Home in just three studio dates involving fewer than sixteen hours of studio time. It took five dates, one overdub session, and twenty-eight hours for Highway 61 Revisited (along with the single “Positively 4th Street”). After three dates and more than eighteen hours in the studio on this new endeavor, Dylan had one unrealized tour de force, one potentially big song, and one marginally popular single, but little in the way of an album. One way to move forward was to bring in veterans of earlier Dylan sessions. Four days after failing on “She’s Your Lover Now,” Dylan recorded with Paul Griffin on piano, William E. Lee on bass, and, fortuitously, Al Kooper (who stopped by to see his friend Griffin but wound up sitting in on organ). Bobby Gregg returned once again to substitute for the Hawks’ Levon Helm on the drums, and was joined this time by the Hawks’ guitarist Robbie Robertson and bassist Rick Danko. Dylan also brought two new songs, the funny, jealous, put-down blues, “Leopard-Skin Pill-Box Hat” (laid aside temporarily after two takes) and “One of Us Must Know (Sooner or Later),” recorded simply as “Unknown.” The results on the latter were stunning. 1

The lyrics are straightforward, even ordinary, tracking a burned-out love affair’s misunderstandings. Dylan experimented with the words inside the studio; the title chorus did not even appear until the sixth take. But the sound texture that makes “One of Us Must Know” so remarkable was built steadily, late into the night and into the next morning. After take seventeen, Dylan heeds the producer Johnston’s advice to start with a harmonica swoop. Crescendos off of an extended fifth chord, led by Paul Griffin’s astonishing piano swells (“half Gershwin, half gospel, all heart” an astute critic later wrote), climax in choruses dominated by piano, organ, and Bobby Gregg’s drum rolls; Robbie Robertson’s guitar hits its full strength at the finale. Intimations of the thin, wild mercury sound underpin rock & roll symphonics. Johnston delivers a pep talk before one last take—“keep that soul feel”—and Gregg snaps a quick click opener, and fewer than five minutes later, the keeper is in the can.

“After That, It Went Real Easy”

“We knew we had cut a good ’un when it was over,” Al Kooper remembers. But despite the successful experiment, the next day’s recording was cancelled, as were two other New York dates. A change in venue had been in the works, and despite the results on “One of Us Must Know,” it would go forward. During the Highway 61 sessions, Bob Johnston had suggested that Dylan try recording sometime in Nashville but, according to Johnston, Grossman and Columbia objected and insisted everything was going fine in New York. Dylan, though, finally went along. He had been listening to Nashville-recorded music since he was a boy and knew firsthand how Johnston’s Nashville friends might sound on his songs. At Johnston’s invitation, the multi-instrumentalist Charlie McCoy had sat in on a Highway 61 session and overdubbed the borderland acoustic guitar runs that grace the released version of “Desolation Row,” strongly reminiscent of the great session-guitarist Grady Martin’s work on Marty Robbins’s “El Paso.” It was an impressive calling-card. “After that,” McCoy remembers, “it went real easy.”

Nashville had been ascending as a major recording center since the 1940s. By 1963, it boasted 1,100 musicians and fifteen recording studios. After Steve Sholes’s and Chet Atkins’s pioneering work in the 1950s with Elvis Presley, Nashville also proved it could produce superb rock & roll as well as country & western, r&b, and Brenda Lee pop. That held especially true for the session crew Johnston assembled for Dylan’s Nashville dates. Trying to plug songs for Presley’s movies, Johnston had hooked up for demo recordings with younger players, many of whom, like McCoy, had moved to Nashville from other parts of the South. Charlie McCoy and the Escorts, in fact, were reputed to be Nashville’s tightest and busiest weekend rock band in the mid-1960s; the members included the guitarist Wayne Moss and the drummer Kenneth Buttrey who, along with McCoy, would be vital to Blonde on Blonde.

Johnston’s choices (also including Jerry Kennedy, Hargus “Pig” Robbins, Henry Strzelecki, and the great Joseph Souter, Jr.—aka Joe South, who would hit it big nationally in three years with “Games People Play”) were certainly among Nashville’s top session men. Some of them had worked with stars ranging from Patsy Cline, Elvis Presley, and Roy Orbison to Ann-Margret. But apart from the A-list regular McCoy (whose harmonica skills were in special demand), they were still up-and-coming members of the Nashville elite, roughly Dylan’s age. (Robbins, at twenty-eight, was a relative old-timer; McCoy, at twenty-four, was only two months older than Dylan; Buttrey was just turning twenty-one.) Although too professional to be starstruck, McCoy says, they knew Dylan, if at all, as the songwriter from “Blowin’ in the Wind” or simply as a guy from New York, an interloper. But they were much more in touch with what Dylan was up to on Blonde on Blonde than is allowed by the stereotype of long-haired New York hipsters colliding with well-scrubbed Nashville good ol’ boys. One of Dylan’s biographers reports that Robbie Robertson found the Nashville musicians “standoffish.” But the outgoing Al Kooper, who had more recording experience, recalls the scene differently: “Those guys welcomed us in, respected us, and played better than any other studio guys I had ever played with previously.”

(What aloofness there was seems mainly to have come from Dylan’s end. Kris Kristofferson, then an aspiring songwriter working as a janitor at the studio, recalls that police had been stationed around the building to keep out unwanted intruders. Asked if he got to meet the star, he told an interviewer, emphatically, he did not: “I wouldn’t have dared talk to him. I’d have been fired.”)

Johnston, apparently at Dylan’s request, helped bring everybody together by emptying the studio of bafflers—tall dividers that separated the musicians to prevent the sounds from one bleeding into the microphone of another. The producer wanted to create an ambiance fit for an ensemble, and he succeeded—so much so that Kenny Buttrey later credited the album’s distinctive sound to that alteration alone. “It made all the difference in our playing together,” he later told an interviewer, “as if we were on a tight stage, as opposed to playing in a big hall where you’re ninety miles apart. From that night on, our entire outlook was changed. We started having a good time.”

Of course, Nashville, for all of its musical sophistication, was not Manhattan. Kooper tells of going to a downtown record store and getting chased in broad daylight by some tough guys who disliked his looks. There were differences inside the studio, too. The Nashville musicians were accustomed to cutting three-to-four minute sides, several a day, where, McCoy says, “the artist and the song was always the number-one item.” Dylan, though, had undertaken some remarkably long songs, and apart from “Visions of Johanna,” none of them was finished. Departing from his reputation for recording rapidly, Dylan kept sketching and revising in his hotel room and even in the studio—sometimes laboriously, sometimes spontaneously, seizing on inspiration so quickly it seemed like free association and sometimes was free association. The first day of Nashville sessions passed briskly enough, but none of the remaining marathon dates ended before midnight, and they usually lasted until after daybreak. Late-night work was not uncommon in Nashville, especially when Elvis Presley was in town, but McCoy relates that it “was just unheard of at that time” to devote so much studio time and money to recording any single song.

Dylan came to Nashville after playing a show in Norfolk, having resumed his touring with the Hawks (now joined by their old backup drummer, Sandy Konikoff). He was determined to finish “Visions of Johanna,” the masterpiece that had initiated the entire enterprise. It emerged in its final recorded form at the first date and inside just four takes (only one of them complete). Dylan now knew what he wanted, and the sidemen quickly caught on: Kooper swirled his ghostly organ riffs around Dylan’s subtle, bottom-heavy acoustic strumming and Joe South’s funk hillbilly bass; Robbie Robertson’s feral lead electric guitar sneaked in at the “key-chain” line in the second verse; Kenny Buttrey mixed steady snare drum with tolling cymbal taps that came to the fore during Dylan’s lonesome whistle harmonica breaks.

The thin, wild mercury sound hinted at in New York was now a fact, spun out of what had been the underlying triad of Kooper’s organ, Dylan’s harmonica, and the guitars—Dylan’s acoustic and Robertson’s electric. Yet Dylan was still experimenting. The date had begun with a song in 3/4 time, “4th Time Around,” which critics call Dylan’s reply to the Beatles’ “Norwegian Wood.” Like “Visions of Johanna,” “4th Time Around” evolved little in the studio and even with Charlie McCoy buttressing the band on his bass harmonica it was a much slighter song, like Bob Dylan impersonating John Lennon impersonating Bob Dylan. In still another vein, numerous takes that reworked “Leopard-Skin Pill-Box Hat” into a sort of “knock-knock” joke complete with a ringing doorbell, shouts of “Who’s there?” and car honks, fell completely flat.

The strangest Nashville recording dates were the second and third. The second began at six in the evening and did not end until five-thirty the next morning, but Dylan played only for the final ninety minutes, and on only one song: “Sad-Eyed Lady of the Lowlands.” He would later call it a piece of religious carnival music, which makes sense given its melodic echoes of Johann Sebastian Bach, especially the chorale “Jesu, Joy of Man’s Desiring.” Unlike “Visions of Johanna,” though, this epic needed work, and Dylan toiled over the lyrics for hours. The level of efficiency was military: Hurry up and wait.

Kristofferson described the scene: “I saw Dylan sitting out in the studio at the piano, writing all night long by himself. Dark glasses on,” and Bob Johnston recalled to the journalist Louis Black that Dylan did not even get up to go to the bathroom despite consuming so many Cokes, chocolate bars, and other sweets that Johnston began to think the artist was a junkie: “But he wasn’t; he wasn’t hooked on anything but time and space.” The tired, strung-along musicians shot the breeze and played ping-pong while racking up their pay. (They may even have laid down ten takes of their own instrumental number, which appears on the session tape, though Charlie McCoy doesn’t recollect doing this, and the recording may come from a different date.) Finally, at 4 A.M., Dylan was ready.

“After you’ve tried to stay awake ’til four o’clock in the morning, to play something so slow and long was really, really tough,” McCoy says. Dylan continued polishing the lyrics in front of the microphone. After he finished an abbreviated run-through, he counted off, and the musicians fell in. Kenny Buttrey recalled that they were prepared for a two- or three-minute song, and started out accordingly: “If you notice that record, that thing after like the second chorus starts building and building like crazy, and everybody’s just peaking it up ’cause we thought, ‘Man, this is it....’ After about ten minutes of this thing we’re cracking up at each other, at what we were doing. I mean, we peaked five minutes ago. Where do we go from here?”

The song came to life as swiftly as any of Dylan’s ever had, requiring only two complete takes.

“Next!”

At the third session, the recording of another epic, “Stuck Inside of Mobile with the Memphis Blues Again,” began at four A.M. after another long wait. The lyrics cohere gradually on a surviving, part-typed, part-handwritten manuscript page, which begins “honey but it’s just too hard” (a line that had survived from the very first New York session with the Hawks). Then the words meander through random combinations and disconnected fragments and images (“people just get uglier”; “banjo eyes”; “he was carrying a 22 but it was only a single shot”), before, in Dylan’s own hand, amid many crossings-out, there appears “Oh MAMA you’re here IN MOBILE ALABAMA with the Memphis blues again.” Inside the studio, several musical revisions and false starts followed, and frustration began setting in, when suddenly, on take fourteen, everything fell into place.

There is some confusion about what happened next. According to most accounts, based on the logs and files kept by Columbia Records, Dylan departed Nashville, then returned with Kooper and Robertson fewer than three weeks later to finish recording. Supposedly, Dylan, in the interim, adapted and came up with the rudiments of eight more songs, most of them in the three-and-a-half- to four-minute range, closer to the traditional pop-song form. Al Kooper, however, insists that the entire album was recorded in a single visit to Nashville, most likely in February, meaning that Dylan had all of the songs sketched out from the get-go; Charlie McCoy, too, remembers only one set of dates, although he concedes he just might be mistaken.

The official documented version jibes better with Dylan’s known touring schedule. It also jibes with the fact that five of the eight songs first recorded after “Memphis Blues Again,” but none of those recorded earlier, include a Tin Pan Alley “middle eight” or “bridge” section—Dylan’s first extensive foray as a writer into that conventional song structure. Nevertheless, the testimony of two key participants carries considerable weight, especially when set against an easily misconstrued paper trail. Whether the Nashville sessions occurred in two clusters or just one, New York hip and Nashville virtuosity converged; indeed, musically, the two seem never to have been much apart. It produced enough solid material to demand an oddly configured double album, the first of its kind in contemporary popular music.

The songs recorded after “Memphis Blues Again” fell into three categories: straight-ahead eight- and twelve-bar electric blues; blistering rock & roll; and everything else. A few of the tracks retrieved sounds from the early New York sessions with the Hawks, but in tighter and richer forms. The others ventured into entirely new territory.

The recording at the fourth Nashville date began well after midnight, with a pair of run-through takes by what sounds like an ensemble of piano, two guitars (one played by Robbie Robertson), bass, organ, and drums. Dylan, rich-voiced, practically croons at times. The lyrics to what was then called “Where Are You Tonight, Sweet Marie?” are not quite done, and Dylan sings some dummy lines (“And the eagle’s teeth/Down above the train line”). The band even changes key between takes; but the song seems basically set—though, on these preliminary takes, Kenny Buttrey shifts his snare beat half a minute or so into the song, and then steadily increases the layered patterns of his drumming. On the last take, the one we know from the album, Buttrey builds the complexities to the point where he is defying gravity or maybe the second law of thermodynamics. By the time Dylan sings of the six white horses and of the Persian drunkard, Buttrey and the song are soaring—and then Dylan launches a harmonica break. The band stays in overdrive, but Dylan and Buttrey, pushing each other forward, nearly pop the clutch. For just under a minute, the song becomes an overpowering rock & roll concerto for harmonica and drums. “Absolutely Sweet Marie” is esteemed chiefly for lines like, “But to live outside the law you must be honest,” and “Well, anybody can be just like me, obviously/But then, now again, not too many can be like you, fortunately”—the second phrase one of many that Dylan has freely mutated in concert over the last forty years. With the sound of “Sweet Marie,” Blonde on Blonde entered fully and sublimely into what is now considered classic rock & roll.

Fewer than twelve hours later, everybody was back in the studio to start in on what Dylan called “Like a Woman.” The lyrics, once again, needed work; on several early takes, Dylan sang disconnected lines and semi-gibberish. He was unsure about what the person described in the song does that is just like a woman, rejecting “shakes,” “wakes,” and “makes mistakes.” The improvisational spirit inspired a weird, double-time fourth take, somewhere between Bo Diddley and Jamaican ska, that on the tape finally disintegrates into a voice in the background admitting, “We lost, man.” That escapade prompted a time out. Robbie Robertson and pianist “Pig” Robbins then joined the band and, laying aside “Just Like a Woman,” they helped change Dylan’s boogie-woogie piano number “What You Can Do with My Wigwam” into “Pledging My Time,” driven by Robertson’s screaming guitar. Only then, after several false starts and near misses, the final proud, pained version of “Just Like a Woman” surfaced.

The concluding date produced six songs in thirteen hours of booked studio time, no time at all compared to the earlier sessions—and serendipity had not departed. They were rolling. “Most Likely You’ll Go Your Way and I’ll Go Mine” was originally a straightforward rock song, dominated by Robertson’s guitar—until Charlie McCoy picked up a trumpet between takes and asked to repeat a little lick alongside Dylan on the harmonica. The song’s sound changed utterly, and for the better. The boys then made quick work of “Temporary Like Achilles,” ending with a performance steered by Robbins’s dusky barrelhouse piano—doubtless the only stroll like it ever to carry the name of a character from The Iliad.

’Round midnight, the mood on the session tape gets giddy. As later related by Johnston to Louis Black, Dylan had roughed out the next song on the piano.

“That sounds like the damn Salvation Army Band,” Johnston said.

“Can you get one?” Dylan replied, either perplexed or joking or a little of both.

After a couple of quick phone calls, the trombonist Wayne Butler showed up, the only extra musician (with McCoy playing trumpet) whom Johnston thought was needed. But at this point in the story recollections clash once again. Legend has it—and more than one of the Nashville musicians have affirmed—that at someone’s insistence, possibly Dylan’s, potent marijuana got passed around, along with a batch of demonic drink ordered in from a local bar. But not everybody was interested. And Charlie McCoy, who by all accounts did not partake, denies categorically that anybody was intoxicated. “It just didn’t happen,” he asserts, either at this session or (with isolated exceptions) at any of the many thousands of others on which he has performed in Nashville. Al Kooper, who had given up alcohol years earlier, agrees that the Blonde on Blonde sessions were sober, and says that the hyper-professionals, Dylan and Albert Grossman, would never have permitted pot or drink inside the studio.

The chatter on the tape is inconclusive, but it sounds more jacked up and high-spirited than seriously ripped—much as Johnston recalled to Black, “all of us walking around, yelling, playing, and singing. That was it!” The excited musicians chip in with their own musical ideas. When Johnston asks for the song’s title, Dylan’s off-the-cuff answer, “A Long-Haired Mule and a Porcupine Here” (later changed to “Rainy Day Women #12 & 35”), is perfectly in character. “It’s the only one time that I ever heard Dylan really laugh, really belly-laugh, on and on, going around that studio, marching in that thing,” Johnston said. In only one or two takes (the tape is a bit confusing about this), the recording is done. And there would be many more tracks recorded that night.

It is now long past the midnight hour and songs are getting churned out at a rapid clip. After each take, Johnston announces, “Next!,” sounding, Texas drawl and all, like a New York deli counterman hustling things along. When the playing of “Black Dog Blues” (later “Obviously Five Believers”) breaks down, Dylan complains, “This is very easy, man” and “I don’t wanna spend no time with this song, man.” Charlie McCoy seizes a harmonica signature line; Kooper lays down a fuzzy bass run on a Lowrey organ; a percussion shaker effaces Buttrey; and Robertson blazes. In four takes, the song is done.

“Next!”

Johnston gets Dylan to start one last retake of “Leopard-Skin Pill-Box Hat” with a clangy lead guitar, but Robertson’s searing Telecaster abducts the song. “Robbie, the whole world’ll marry you on that one,” Charlie McCoy raves.

“Next!”

“I Want You” had been Kooper’s favorite song all along, and he has said Dylan saved it for last just to bug him. More like “Memphis Blues Again” than like the other songs cut at this final session, “I Want You” starts off in manuscript with lyrical experiments that fail: “The deputies I see they went/Your father’s ghost…to hant [haunt]/Just what it is that/Want from you.” Once Dylan has finished writing, though, little changes through five takes except the tempo. Johnston expresses surprise that Dylan can sing all the words so swiftly; Wayne Moss’s rapid-fire sixteenth notes on the guitar are nearly as impressive. And then the recording of Blonde on Blonde ends.

Ghost, Howls, Bones, and Faces

After mixing the record, it was obvious that the riches of the Nashville sessions could not fit on a single LP.

During the recording, dating back to October and through all of the changes in personnel, there had been some constants. Al Kooper played on every track of the final album, his contributions essential not just as a musician and impromptu arranger but as a conduit between Dylan and the changing lineup of session men. Kooper’s Nashville roommate, Robbie Robertson, had been involved from the start and refined his playing from unsubtle rock lead to restrained, even delicate performances, along with blues keenings that won praise from some of the most discerning ears on the planet. Kooper and Robertson, familiar with Dylan’s spur-of-the-moment ways, also helped as translators for the Nashville musicians. “They couldn’t have any charts or anything, so they were following where he was putting his hand,” Johnston told Black. “It was so spontaneous. Al Kooper used to call it the road map to hell!”

And, of course, dominating everything was Bob Dylan’s voice, figuratively as the author and literally as one of the album’s main musical instruments. Dylan did not completely relinquish his own version of what Jack Kerouac had called “spontaneous bop prosody,” but crucially, in violation of Kerouac’s alleged miraculous practice, Dylan constantly and carefully revised, as he always had and still does, even to the point of abandoning entire songs. Changing the line “I gave you those pearls” to “with her fog, her amphetamine, and her pearls” was one example out of dozens of how Dylan, in the studio and in his Nashville hotel room, improved the timbre of the songs’ lyrics as well as their imagery. And Dylan’s voice, as ever an evolving invention, was one of the album’s touchstones, a smooth, even sweet surprise to listeners who had gotten used to him sounding harsh and raspy. By turns sibilant, sibylline, injured, cocky, sardonic, and wry, Dylan’s voice on Blonde on Blonde more than made up in tone and phrasing what it gave away in range. It was even more challenging to sing out than it was to write out, “But like Louise always says/‘Ya can’t look at much, can ya, man’/As she, herself, prepares for him,” in “Visions of Johanna,” but Dylan pulled it off.

Blonde on Blonde was, and remains, a gigantic peak in Dylan’s career. From more than a dozen angles, it describes basic, not always flattering, human desire and the inner movements of an individual being in the world. The lyric manuscripts from the Nashville sessions show Dylan working in a ’60s mode of what T.S. Eliot had called, regretfully, the dissociation of sensibility—cutting off discursive thought or wit from poetic value, substituting emotion for coherence. The less finished lyrics-in-formation that survive in manuscript—like the archipelago of flashing images that lead, finally, to intimations of “Memphis Blues Again”—would never completely lose their delirious quality on the album. Yet even with its ruptures between image and meaning, even with its Rimbaud-like symbolism and Beat generation cut-up images, Blonde on Blonde also evokes William Blake’s song cycle of innocence and experience, when it depicts how innocence and experience can mingle, as in “Just Like a Woman,” but also when it depicts the gulf that lies between them. Many of the album’s songs, for all of their self-involved temptations and frustrations, express a kind of solidarity in the struggle to live inside that gulf. Although the songs are sometimes mordant, even accusatory, they are not at all hard or cynical. Blonde on Blonde never degrades or mocks primary experience. Its doomed, hurtful love affairs do not negate love, or abandon efforts to remake love, to liberate it: quite the opposite, as is shown in the litanies of its concluding psalm to the mysteriously wise Sad-Eyed Lady. Blonde on Blonde, as finally assembled, is a disillusioned but seriously hopeful work of art.

The album is Blakean in other ways as well. As the young critic Jonny Thakkar has pointed out, there are allusions to Blake’s writing in the third verse of “Visions of Johanna,” where the song’s perspective temporarily shifts to that of the delicate but prosaic Louise, and which mocks Louise’s distracted lover, the singer, as “little boy lost.” The phrase repeats the title of one selection in Songs of Innocence and one in Songs of Experience—contrapuntal poems in which Blake’s little boy is first disappointed when he pursues a holy vision—“The night was dark, no father was there/The child was wet with dew/The mire was deep, and the child did weep/And away the vapour flew”—and later is cruelly punished. On his earlier recordings, Dylan asked questions and supplied answers, adhering to the standard folk-ballad form if only to say that the answer was blowin’ in the wind. But some of his songs on Blonde on Blonde, like some of Blake’s poems in Songs of Experience, pose questions without providing any answers at all. Blake’s “The Tyger” consists entirely of unanswered questions—“What immortal hand or eye/Could frame thy fearful symmetry?”—and so does “Sad-Eyed Lady of the Lowlands.”

The album changed how listeners and ambitious writers and performers thought about Bob Dylan and about the possibilities of rock & roll. It also affected its makers. A year later, after the breakup of the group he was in, the Blues Project, Al Kooper headed a new band that fused jazz with rock & roll and pop but took its name from an album of Johnny Cash’s released in 1963, Blood, Sweat, and Tears. Soon after they finished Blonde on Blonde, several of the Nashville musicians reassembled as the Mystic Knights Band and Street Singers. Under producer Bob Johnston (renamed, for the occasion, “Colonel Jubilation B. Johnston”), they recorded and released on Columbia one of the most obscure rock albums of the 1960s, Moldy Goldies—“as goofy as we could be,” Charlie McCoy remembers—sending up hits from the Young Rascals’ “Good Lovin’” to Sonny and Cher’s “Bang Bang.” Each takeoff sounds a lot like a hit of their own, namely “Rainy Day Women #12 & 35,” except with one “Luscious Norma Jean Owen” singing instead of Bob Dylan, her Southern voice hovering between coyness and confusion.

Dylan helped oversee the mixing of Blonde on Blonde, then departed on his famous, furious world tour with the Hawks (Mickey Jones now sitting in for Levon Helm). Despite the heckling in England and France, the instant commercial success of “Rainy Day Women” back home matched the earlier success of “Like a Rolling Stone,” and it seemed as if Dylan’s new sound had blasted away the booers for good, at least in America. Artistically complicated though it was, Blonde on Blonde affirmed Dylan’s enormous new popularity, reaching No. 9 on Billboard. In July, though, Dylan cracked up his motorcycle on a back road outside Woodstock; after recuperating, he recorded near Saugerties what became known as The Basement Tapeswith all of the Hawks, soon renamed the Band. He would not return to a Columbia recording studio until a year and a half after he’d completed Blonde on Blonde—back in Nashville with Charlie McCoy and Kenny Buttrey by his side, and with Bob Johnston producing, to complete John Wesley Harding, which was released just after Christmas. Innocence and experience remained on Dylan’s mind, but the stripped-down song that took shape quickly during the first session, “Drifter’s Escape,” sounded completely unlike what had come before. Bob Dylan refused to be locked up or pinned down, even to the rapturous sounds of Blonde on Blonde. He drifted, as he still drifts, toward new peaks and valleys and peaks.

1 One writer’s listing for this session credits Michael Bloomfield on guitar and William E. Lee on bass; another listing omits Paul Griffin. The session tapes show that although Lee played on the early takes of “Leopard-Skin Pill-Box Hat,” none of which appeared on the album, Rick Danko was the bassist on “One of Us Must Know.” The tapes also affirm that Robbie Robertson played guitar and that Griffin was, indeed, the pianist. There is significance to this seemingly pedantic point: After all these years, Bobby Gregg, Paul Griffin, and Rick Danko, whose names have never appeared in the album's liner notes, deserve their share of credit for playing on Blonde on Blonde. My thanks to Diane Lapson for helping to sort out the identities of the various musicians on the recordings, as well as to Jeff Rosen and Robert Bowers for guiding me to and through the recordings themselves.