Remembering Cormac McCarthy

In memory of the man, his work, and his origins

By Oxford American

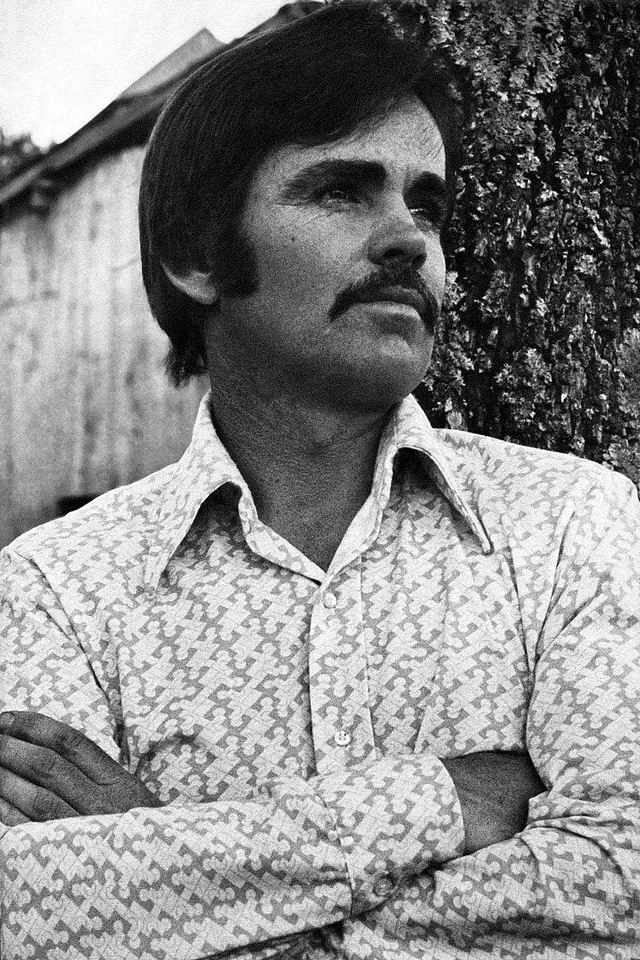

Photograph of Cormac McCarthy by David Styles. Used as back cover of Child of God, 1973. Courtesy Wikimedia Commons

Today, the Oxford American joins the literary world in mourning Cormac McCarthy, who died on Tuesday at the age eighty-nine. We are grateful to have had the opportunity to share a literary ode to the Southerness at the core of his work just months before his death.

In our spring issue, OA contributor Christopher C. King wrote a long essay about McCarthy’s two recent—and now last—novels, The Passenger and Stella Maris. King’s aim, he said, was to give the notably press-averse writer the “big, literary treatment.” Once it was said and done, King’s essay landed as a cerebral contribution to a gothic-leaning issue.

King wrote: “From the publication of his first novel, McCarthy has offered us stories that take place principally in the American South and Southwest, in the Appalachian wilderness and in the desert scree on or near the Mexican border. Though he was not born in Tennessee, he spent the majority of his early life in Knoxville, was raised a Catholic, and eventually settled in New Mexico. There is a way of being that McCarthy shares with the cultures and the territories below the Mason-Dixon Line, a sort of understated matter-of-factness that is not in the least bit cynical.”

The Road might be McCarthy’s best-known work. Published in 2006, it won a Pulitzer Prize. Nearly every review of the book notes that it is “sparse” and “violent.” These terms are possibly the most noted descriptors of his collected work. I’d like to add that “beautiful” also applies, and that the duality of his work is the beauty that can be found in the terror: sublimity, perhaps, that stares straight at the core of being human. He leaves us with twelve novels, two published screenplays, two plays, and a few more pieces of prose.

In searching for words to honor his work and his memory, our multimedia editor and arbiter of our archive, Patrick D. McDermott noted: “McCarthy is mentioned or alluded to at some point in nearly every single issue.” McCarthy’s literary contribution is a shorthand and reference point for American fiction of the late twentieth century. The three pieces shared below engage most directly with McCarthy—the man, his origins, and his work.

Each of these stories get at the most intriguing element of McCarthy, beyond the vast oeuvre he leaves behind: his disdain for self-promotion, a reticence which King attests “makes us pay attention to what is on the page.” In 2017, Noah Gallagher Shannon traveled to “the city of Knoxville, where McCarthy has become something of a patron saint.” He follows Dr. Wesley Morgan Jr. who has made a life’s work of tracing McCarthy’s inscrutable origins in East Tennessee.

In a column from 1998, journalist and essayist Hal Crowther describes how McCarthy’s publisher “engineered [his] commercial success” by having him “submit to an interview” with the New York Times. Although Crowther later spends time with McCarthy and offers insight on the enigma, his first meeting is one of starstruck awe.

We hope you join us in re-reading his works, a particular portrayal of the twentieth and twenty-first centuries, and in honoring the man and his legacy through our contributors’ words below.

—Allie Mariano, managing editor

God's Silence, Humanity's Deafness

On Cormac McCarthy’s two new novels

In Issue 120, Christopher C. King writes at length aboutThe Passenger and Stella Maris, the final two novels McCarthy would publish in his lifetime. “As a thinker and writer of the South, [McCarthy] wants us to consider the outcomes, moral and otherwise, of living in a godless world,” King proposes, before speculating about how McCarthy's own relationship to mortality shaped his late-career writings:

I like to think that through his incessant crafting of stories he discovered, as stated in The Passenger, “that what drives the tale will not survive the tale.” What drives the tale but does not survive the tale is the author, the teller. With this realization of truth, the voice of the author becomes elevated, almost transcendent, because it can conjoin lyricism with the profound issues of life, death, and the suffering in between these two states.

Old Woods and Deep

Traces of Cormac McCarthy’s Knoxville

Released amidst the Oxford American's twenty-fifth anniversary celebrations, Issue 98 finds Noah Gallagher Shannon traveling to East Tenessee, where McCarthy scholar Dr. Wesley Morgan Jr. offers up a tour of the late author's Appalachian stomping grounds, including a visit to his childhood home, which burned down in 2009:

With so many of the typical routes toward biography blocked, I figured Morgan might have some insights, ideas of how to reconcile the hugeness of McCarthy’s legacy with the mystery of his absence. Full as his books are of death cults and gothic flora and wheezed backcountry wisdom, it was easy to imagine McCarthy as a character of his own invention—stoic, intense, dedicated to handcraftsmanship. But what turned out to be harder, as Morgan’s work proved, was picturing him with any definition. So when I arrived in Knoxville in May, interested in seeing some of the landscapes and events portrayed in McCarthy’s fiction, as well as the places and things he’d touched while working on them, I asked Morgan if he’d take me to the site of the fire, and he agreed.

The End of the Trail

Cormac McCarthy should revisit his home in Tennessee

In the Issue 23 edition of his National Magazine Award-nominated Oxford American column Dealer's Choice, Hal Crowther writes that “there are only three things, none of them uncommon, that might keep you from admiring McCarthy: a tin ear, a weak stomach, or a hopeful heart. If it’s solace you’re seeking, stay away.” He continues by recounting his first run-in with the late writer, an interaction that was befittingly squirm-inducing:

My story with Cormac McCarthy is one of a devout reader and a writer he reveres. Idolatry was never a weakness of mine. Only one encounter with a legend had ever left me at a loss for words, and that was in front of the visitors’ dugout at Shea Stadium, when I turned suddenly to find Willie Mays grinning at me and holding out his hand.

I was only twenty-five then. When I was pushing fifty, Cormac McCarthy produced a similar social dysfunction. I hope it doesn’t embarrass Clyde Edgerton, a fair novelist himself, if I describe our behavior when McCarthy, wearing his name tag, materialized improbably at a cocktail party in Cashiers, North Carolina. Clyde and I sort of backed ourselves to within earshot of his conversation, like awed undergraduates at a book signing. I’m not sure we’d have introduced ourselves at all if McCarthy hadn’t turned and offered his hand, like Willie Mays.

“How do you like where you’re living?” somebody asked him, and he answered, “I never liked any place much.”