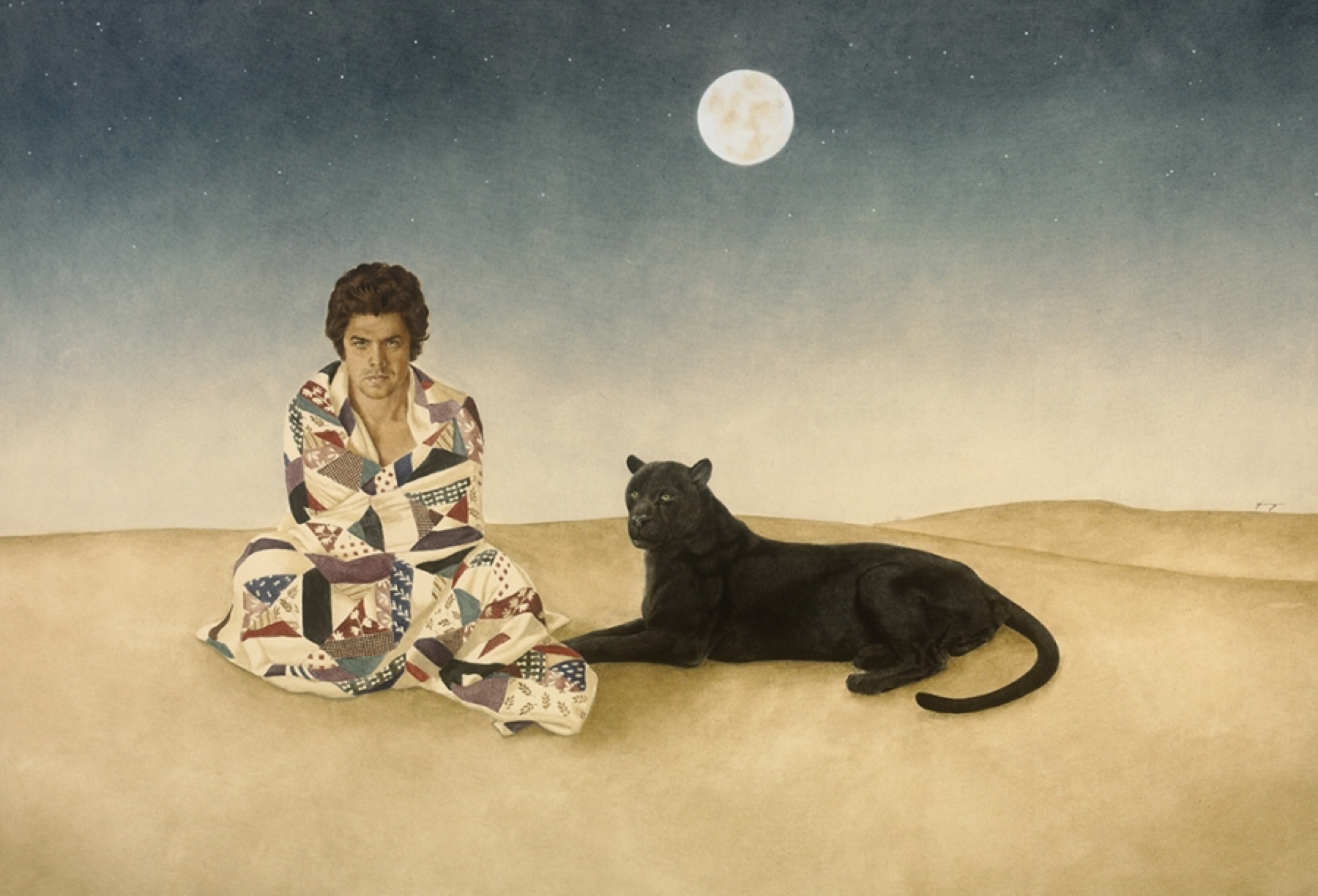

“Loss of the Killing Instinct” (1977), acrylic on canvas. © Ginny Stanford

Last Panther of the Ozarks

By Ansel Elkins

Books discussed in this essay:

What About This: Collected Poems of Frank Stanford, edited by Michael Wiegers. Copper Canyon Presss, 2015. 764 pages.

Hidden Water: From the Frank Stanford Archives, edited by Michael Wiegeres and Chet Weise. Third Man Books, 2015. 200 pages.

In my early days I was a student of all forms. I learned everything and nothing. I practiced the katas of poetry. I listened to the blues. Having the equilibrium of a poet, I kept falling in love.

— “With the Approach of the Oak the Axeman Quakes”

“Don’t go down the rabbit hole,” my husband tells me, but it’s too late. It is 3 A.M. and I am still at my desk, the lamp burning hot on my notebook. I have spent the past fourteen hours scouring this book for hidden meanings, and it’s leading me deeper and deeper into a strange world of psychedelic vision: I can dream watching the shooting stars in a black dog’s eye / I can dream a piano of bourbon / I can dream on Beale / I can dream even though I am asleep in a star drift. This is what obsession looks like: I am Dante following my Virgil, but if I journey too far into this underworld I fear I may not return. Yet this foreboding, mysterious landscape is familiar to me, so the allure is difficult to resist. “Just fifteen more minutes and I’ll come to bed,” I tell him, although I know this is a lie.

When I was twenty-three, I had a heady love affair with this beautiful Byronic poet from Mississippi, Frank Stanford. No matter that he was already dead—had been dead for years before I was born—or that he’d shot himself while his wife and his lover were in the house with him. I was poor and idealistic and living in Arkansas, the same state where he worked and died, when I found my way to his poems. When I first opened Stanford’s slim book of posthumously published selected work, The Light the Dead See, every word rang true and glowed like burning coal. I was enraptured by his recklessness, his rebelliousness, his loneliness; I drank up his language like whiskey and was pulled into his dangerous, nocturnal world full of energy and eroticism and death.

The first poem I memorized from The Light the Dead See was “Memory Is like a Shotgun Kicking You near the Heart,” which originally appeared in Stanford’s 1978 collection Crib Death. It has remained with me a decade on. The poem begins:

I get up, walk around the weeds

By the side of the road with a flashlight

Looking for the run-over cat

I hear crying.

I think of the hair growing on the dead,

Any motion without sound,

The stars, the seed ticks

Already past my knees

The narrator describes a solitary night walk in the woods (through the “deer path / Down the side of the hill to the lake”), shining his flashlight on passing scenes, searching for something lost, yet unknown even to the searcher. I too was possessed by restlessness, rising to wander after midnight in my own loneliness—questioning why I was more at home in the night than the day. The poem ends where it began:

When I get home

I drink a glass of milk in the dark.

She gets up, comes into the room naked

With her split pillow,

Says what’s wrong,

I say an eyelash.

Trying to describe the effects of a poem, the mysterious mechanics of its power, is like trying to describe how good sex is good. As Jorge Luis Borges said, “If you don’t feel poetry, if you have no sense of beauty … then the author has not written for you.” This poem, I felt immediately, was mine.

Sometimes reading Stanford I sense that his poems are coded, that if I could only lift the veil of his secret language I’d uncover a whole other world of meaning. He wrote from the historical id, charting the unconscious mind of the South—nightmarish, violent, haunted—along with an idea of himself, both real and invented, which was steeped in personal loss and fragmented identity. Like the night sky, Frank Stanford changes before my eyes—even still. He is a constant stranger: elusive and unknowable, unreachable as the moon that rides brightly across the black.

like a river comes to love its journey

I came to love you in dreams

— “Swimming towards Women”

Since his suicide in June 1978, Stanford has stood on the margins of American poetry. His work is rarely included in major contemporary anthologies and he risks the plight of many idiosyncratic, difficult, or weird artists: that of the cult favorite, to be championed by a passionate few (or worse, to be written off as a folkie regionalist). During Stanford’s lifetime, the independent, Seattle-based Mill Mountain Press published his books, many of which have fallen out of print, making it difficult for all but his most dedicated followers to find his work. But with the release of What About This: Collected Poems of Frank Stanford in April, his ghost has been conjured up. Edited by Michael Wiegers, Copper Canyon Press’s executive editor, the collection presents Stanford’s published and unpublished poems, short prose—including an essay about his creative process, “With the Approach of the Oak the Axeman Quakes”—interviews, drafts, photographs, and ephemera, as well as excerpts from his ecstatic four-hundred-page epic, The Battlefield Where the Moon Says I Love You. At last comes Stanford’s chance to be read by a wider audience. To those readers unacquainted with his poetry, in the poet’s own words: “you are getting into a different and strange country.”

This beast of a book arrived in my mailbox last May. My first thought was that the title What About This feels strangely inconsequential next to Stanford’s previous works: The Singing Knives, Ladies from Hell, Arkansas Bench Stone, and the macabre Crib Death—all instantly recognizable as coming from his particular world and lexicon. The cover bears a blue-washed photo of Stanford crouching in a field of wildflowers, a paperback in his hands. He gazes outward from beneath leonine black curls and his stern, pensive brow. (“The dark-eyed orphan,” he called himself in one poem.) The book is as handsome and imposing as he was—yet I hesitated before opening it. Like an old lover, the poet’s myth had been cast in my memory, and now I risked breaking it open and finding not flaming poems but smoke. I was afraid to confront the possibility that my love for his work had faded. “There’s nothing cold as ashes,” sings Loretta Lynn, “after the fire is gone.” Some say this about Thomas Wolfe, that you can only really read him when you’re young. That only the young can be swept away with that language of exuberance, so enchanted with those endless sentences, that boundless energy and vigor that is intoxicated by itself. When I checked my mailbox that day, it had been eight years since I’d read a poem by Frank Stanford.

The collection sent me reeling back to 2005, the year I lived in Conway, Arkansas, and worked for this magazine. I’d relocated from Portland, Oregon, to a place where I knew no one. I moved into a decrepit, ramshackle two-story house, the only woman with five to eight (depending on the week) male roommates—Marxists, musicians, aspiring novelists. At times we lived like squatters, without heat or electricity. I slept on a twin mattress on the floor, washed my hair in the kitchen sink, and read by candlelight when we couldn’t make the electricity bill.

Stanford’s poems lived among us in that house; we passed them around with the bottles of whiskey. The rawness, the energy, and the urgency of his language coursed through me. “He was crazy, he was a dreamer, lovely and dark,” Stanford writes in “The Lacuna.” His passion and musicality echoed Federico Garcia Lorca and my favorite Latin American poets like Pablo Neruda. Before I read Stanford, my love of Southern literature came mostly from fiction—Faulkner, O’Connor, Capote, Hurston, Welty, Wolfe—but I had not yet met a kindred spirit in verse whose voices and views of the South resonated with my own. Having grown up in Alabama at the close of the twentieth century, I was a young writer searching for a way to transform my personal history into my own vision and creative voice. I had been away for years—college in the northeast, followed by the stint in Portland—and now, living in Arkansas, I was re-immersed into my native culture and people. My love affair with Stanford was a love affair with being young in the Dirty South.

In Stanford’s writing, I encountered a lawless language and a feral imagination unlike anything I’d read before. His poems are set in honky-tonks and juke joints and backwoods pool halls laden with whiskey, gambling, sex, and violence. Stanford was influenced by country and blues music. He even titled several of his poems after Jimmie Rodgers’s lonesome blue yodel, a cry that had reached me deeply and which later gave my first book its name. “Freedom, Revolt, and Love,” another poem that held me hostage from the first reading, was published the year after his death in the 1979 collection You. Revisiting it in What About This, I felt myself drawn back into Stanford’s gravity, and marveled again at his ability to set a scene freighted with doom:

They caught them.

They were sitting at a table in the kitchen.

It was early.

They had on bathrobes.

They were drinking coffee and smiling.

She had one of his cigarillos in her fingers.

She had her legs tucked up under her in the chair.

They saw them through the window.

The moment is loaded with imminent violence. You sense it as soon as you enter his world; the ominous pervades his writings—in tone, syntax, line length, imagery, and metaphor—the specter of death looms over every line, as if the people he writes about are cursed. The indefinite pronouns obscure the characters but the short, tense sentences and end-stopped lines heighten the drama as it unfolds before our eyes and we witness the intruders come in “through the back”:

The stove was still on and burned the empty pot.

She started to get up.

One of them shot her.

She leaned over the table like a schoolgirl doing her lessons.

She thought about being beside him,

being asleep.

They took her long grey socks

Put them over the barrel of a rifle

And shot him.

He went back in his chair, holding himself.

She told him hers didn’t hurt much,

Like the fall when everything you touch

Makes a spark.

I admire how Stanford enlaces tenderness in this scene of gruesome violence, which, in his world, occurs as abruptly as a summer thunderstorm. As do moments of passion that flash into being with all the swiftness of wildfire in a dry season.

It has been encouraging to follow the initial response to the collection; it seems Stanford may finally get the wide recognition he deserves. In the New Republic, Jay Deshpande wrote, “What About This marks a rare moment, when a critical and completely original American voice is recovered after decades and takes its rightful place in the canon.” In the New York Times, Dwight Garner called Stanford an “important and original American poet—sensitive, death-haunted, surreal, carnal, dirt-flecked and deeply Southern.” And in the Arkansas Times, Matthew Henriksen argued for Stanford’s influence: “The poetry is indeed written exhaustively, and has an unrelenting energy that might, most importantly, catch the attention of younger readers and help them potentially seek their own voices as writers.”

Stanford was astoundingly prolific, and there’s no way his irrepressible exuberance can be contained in any single volume—though Copper Canyon’s collection represents an unprecedented effort. In addition to unpublished manuscripts, What About This offers other treasures, like a facsimile of the rejection slip from the Academy of American Poets’ Walt Whitman Award, to which Stanford submitted The Battlefield Where the Moon Says I Love You in 1974:

Dear Mr. Stanford:

We just cannot accept a manuscript for the W. Whitman Award competition that is significantly longer than 100 pages. If you are not able to cut down your entry to that length, then you should not send it in to this particular competition.

Alan Dugan, the Pulitzer Prize–winning poet, had recognized Stanford’s originality and championed the twenty-six-year-old’s work. When Dugan heard about the dismissal, he wrote to the organization’s assistant executive editor, and his letter is also included in What About This:

I think you have made a mistake. Stanford is a brilliant poet and just because he is ample in his work, like Whitman, is no reason not to consider his manuscript… . I’ve been reading his work for the last four years or so and I’m convinced of his genius as a writer.

The Whitman Award is a competition for poets who have not yet published a first book, so Stanford wouldn’t have been eligible anyway (his debut, The Singing Knives, was published in 1971). But the Academy of American Poets’ refusal to consider Stanford’s manuscript due to its Whitmanesque length is indicative of why it’s taken critics several decades to awaken to this blue Andalusian rooster crowing its strange and glorious tune right outside their window.

In late July, Third Man Books, an imprint of Jack White’s Third Man Records in Nashville, released Hidden Water: From the Frank Stanford Archives as a companion edition to What About This. Edited by Wiegers and Chet Weise, the collection offers previously unpublished letters—to Dugan, Allen Ginsberg, and others; more drafts and poems; and photographs, including a few from the filming of Stanford’s surrealistic 1974 autobiographical short film, It Wasn’t a Dream, It Was a Flood. There is also a partial list of the contents of his record collection at the time of his death, which included blues and jazz. Also released, as a download, is a previously unheard recording of Stanford reading his poem “The Boathouse,” in a voice that sounds uncannily like James Dickey’s, defiant and bold, with an opera recording providing an appropriately disorienting counterpoint in the background. The cover of Hidden Water features a gorgeous acrylic portrait by Ginny Crouch Stanford, the late poet’s wife, which she painted at his request, an homage to Henri Rousseau’s “The Sleeping Gypsy.” Titled “Loss of the Killing Instinct,” it depicts Stanford sitting cross-legged, wrapped in a quilt, beside a black panther beneath a full moon with faint stars in the canvas of the night sky.

so far I am the only poet of my kind in this country

though you have probably noticed by now that I am from another country

—The Battlefield Where the Moon Says I Love You

I was recently at a cocktail party in Connecticut, standing alone in a manicured, Japanese-inspired garden where a crowd of strangers held wine glasses and talked in stiff, polite ways. The razor-perfect rectangular hedges and strict geometry of the space made it difficult to move freely so I helped myself to the hors d’oeuvres and pretended to admire the flowers, some of which, I noticed, were plastic. At one point, I found myself in conversation with a middle-aged poet in a tie. He made a few remarks, then proceeded to talk extensively about himself. His nose was curved into a slight sneer. Eventually he asked what I was working on. An essay about Frank Stanford, I told him. The poet in the tie looked disinterested. “I’ve heard his name. He’s from somewhere in the South, right? Is he any good?”

Before I could tell him that Frank Stanford is more than just “good”—that he was a prodigy—the poet in the tie interrupted me to ask the server for another glass of wine. I could never imagine Frank Stanford at a garden party in Connecticut, well-behaved and wearing a tie. In the photographs I’ve seen, he’s more often than not barefoot, with at least the top three buttons of his shirt undone or just plain missing. The Mississippi-born, Memphis-bred poet once shot off a double-barreled shotgun in the middle of a party he’d thrown for Allen Ginsberg because he considered some of the guests to be “lightweights,” his longtime friend Bill Willett recently recalled to Men’s Journal. “All the lightweights left.”

Stanford attended high school at Subiaco Abbey, a Benedictine monastery in the foothills of the Ozark Mountains, where he converted to Catholicism and was profoundly influenced by the monks. In 1966, he enrolled at the University of Arkansas at Fayetteville, and though he impressed his teachers—the poet James Whitehead admitted him, a freshman, into a graduate poetry workshop—Stanford dropped out after two years and quickly claimed a persona as an untamed sojourner on the margins of the civilized world. His school was the Mississippi Delta with its bayous and levees, peopled by a cast of characters with names like Born In The Camp With Six Toes, Tang, Ray Baby, Bobo, and Dark. He read as voraciously as he wrote. “A lot of people label all Southern things as ‘Southern grotesque,’” Stanford once said in an interview. “I’ve had some Yankee say, ‘This is Southern grotesque.’ And I’ve seen men actively come out against anything that can be construed as Southern.” His deeply literate work is a rebuke to those who would dismiss his talent because he wrote of and from the Deep South, because he was a stubborn autodidact, because he often repeated motifs. As Dwight Garner noted in his review of What About This, Stanford “has sometimes been viewed as a primitive. He wasn’t one. It’s apparent in his poems that he had read and seen almost everything; his cultural memory was long.” He was proudly a renegade poet who wrote with vitality and immediacy, inventing a cosmology of his own design.

When you take the lost road

You find the bright feathers of morning

Laid out in proportion to snow and light

And when the snow gets lost on the road

Then the hot wind might blow from the south

And there is sadness in bed for twenty centuries

And everyone is chewing the grass on the graves again.

— “Circle of Lorca”

In 1972, Stanford suffered a breakdown, after the dissolution of his first marriage, which had lasted less than a year. At the urging of his mother, he checked himself into a mental hospital in Little Rock. The next few years were itinerant and productive. His first publisher, Irving Broughton, whom he met in the summer of 1970 at the Hollins Conference in Creative Writing and Cinema in Virginia, sparked Stanford’s interest in filmmaking, and the two traveled the northeast and to New York in 1972, interviewing poets and writers for a three-volume series, The Writer’s Mind. He spent time in Eureka Springs, Arkansas, where he established a classic film series at the Center Street Theatre and met and married a painter named Ginny Crouch. All the while, he wrote, publishing his first collection of poetry, and continuing work on The Battlefield.

In 1975, Stanford returned to Fayetteville. He worked as an unlicensed land surveyor and established Lost Roads Press in an effort “to reclaim the landscape of American poetry” by publishing the works of talented young poets whose voices went unrecognized by the conventional presses. He befriended writers in the University of Arkansas’s MFA program, including the poet C. D. Wright, a recent graduate with whom he soon began an affair that would last until his death. With his wife, Ginny, residing at her family’s farm in southern Missouri, he was able to maintain an alternate life, living with his lover in Fayetteville. Together Stanford and Wright operated Lost Roads out of the garage of her rented house and, in 1977, the press published as its first volume Wright’s Room Rented By A Single Woman. After Stanford’s death, Wright took over directorship of the press and continued its mission, in her words, to publish “the beautiful wild poets we grow from the road.”

Lost roads—the image resonates. I’ve been chasing down them like a bloodhound in pursuit of Stanford’s ghost. Just when I think I’ve got him in my sight, he evaporates like a mirage, a wave of light shimmering at the vanishing point of the long hot highway I’ve been traveling. When he was a boy, Frank’s mother called him a “chosen child.” Then in 1968, when he was twenty, she revealed to him that he was in fact adopted. Was this the original lie that begat a lifetime of lies and fabrications? If he no longer knew who his parents were, then they could be anyone, and thus he could weave his origins into a grand legend. He could become the true bastard son of the literary South.

While in Connecticut, I visited the Beinecke Rare Book & Manuscript Library at Yale, which holds Stanford’s papers, bequeathed by C. D. Wright and Ginny Stanford, co-executors of his estate. There I came across Wright’s notes from a phone conversation she had with Bill Willett, Stanford’s high school friend and football teammate at Subiaco. It appears she, too, was trying to construct a reliable biography:

Learned of his adoption in 68

made huge difference to him

that he had been misled

as youth claimed his lineage traced to

Earl of Sandwich + proud of that

(from his mother’s side)

Frank Stanford was born Francis Gildart Smith on August 1, 1948, in Richton, Mississippi, at Emery Memorial Home and Hospital for unwed mothers. Although the Home burned under “mysterious circumstances” in 1964 and its records were lost in the blaze, Beinecke holds a copy of his Decree of Adoption, which gives the only solid information we have about his origins. “1949,” a previously unpublished one-line poem included in What About This, may reveal the poet’s resentment toward his unknown birth mother: “A whore blowing smoke in the dark.”

Shortly after his birth he was adopted by Dorothy Gilbert Alter, a divorcee. The following year, Dorothy adopted a second child, Frank’s sister Ruth, who seems to have been a glimmer of sweetness in Stanford’s childhood. On September 22, 1949, the Delta Democrat Times published a brief account of Ruth’s homecoming:

Small Francis Gildart Alter today heads a welcome committee made up of family and friends, who are greeting Bettina Ruth Alter who was born last Thursday and has come to make her home in Greenville with Mrs. Dorothy Gilbert Alter and Francis. The head welcome seems to think that the new arrival belongs to him alone and perhaps that isn’t a bad idea as every little girl needs a big brother to smooth the road for her.

Years later, in a poem titled “The Unbelievable Nightgown,” from his second book, Shade (1973), Stanford writes:

Of my sister I can only say

She was like a long feather

Who could breathe under the water

And snarl without lipstick

Or meaning it

Her hair was like a wildcat

Caught in some fisherman’s nets

She wore it like a Cajun whore

His complicated, often negative, depictions of women are just the most obvious manifestation of how boys were celebrated in the world of Southern men. “Alabama eats its young,” my grandfather once told me. Perhaps this burden of Southern manhood, of having to be the golden boy, the chosen child, consumed the young Frank Stanford, too.

In 1952, Dorothy Alter married Albert Franklin Stanford, an older wealthy engineer, and moved the family to his home in Memphis. A. F. Stanford worked for the U.S. Army Corps of Engineers, building levees along the Mississippi River and its tributaries. Frankie, as Stanford was called, spent his childhood summers with his stepfather in the levee camps, which inspired his most ambitious work, The Battlefield Where the Moon Says I Love You. The 15,283-line poem was carved from a longer work titled “St. Francis and the Wolf,” which he began writing while in high school. In The Battlefield he weaves his personal history into mythology, creating his own Odyssey, his own Beowulf. “i francis gildart knight of the levees and / rivers and ships,” he proclaims. Full of bravado and boyish, adolescent posturing, he brags of his exploits and outlaw spirit. The poem is a kind of bildungsroman that features Stanford’s alter ego, Francis Gildart, the heroic twelve-year-old boy at the story’s center. Although as sprawling as Whitman’s Song of Myself, it is more of a Huckleberry Finn tale of a boy’s coming-of-age adventure in the Mississippi Delta, which he casts as a mystifying, magical, and violent landscape. It is a phantasmagoric and psychedelic work, an amalgam of biblical, vernacular, and mythological references, written in a heated frenzy. At times nightmarish, at times a gorgeous reverie, The Battlefield is a story of the South in the era of Jim Crow; at its heart is the young narrator’s grief over the lynching of his friend Sylvester, a wrongfully accused black man. Francis Gildart goes with Sylvester’s mother to cut him down from the tree and give him a proper burial. Stanford wrote this epic in a spasm of energy and anger over the many injustices faced by blacks in America. Sadly, its lessons are as relevant today as they were in the 1960s.

“Although I don’t want people at the end of it to say that this was obviously a poem, I want it to have the traits of a poem—as a symphony has the traits of a symphony,” Stanford told Irv Broughton, in 1974. The Mississippi River imbued Stanford’s poetry with its mythic power and rhythms: “What I want to do is use movement and rhythm on different levels. I want it to be like the reader was going into reading the poem as they were going for a boat ride in some swift water.” Greenville, the setting of Stanford’s earliest years, was the place that inspired William Alexander Percy to write Lanterns on the Levee, and where a young Walker Percy and Shelby Foote became best friends, driving together on a literary pilgrimage to Rowan Oak to visit Faulkner. Little Frank even attended the same Episcopal Sunday School as Foote’s daughter Margaret. The family of Ellen Gilchrist, who studied under Eudora Welty, lived just down the road a piece in Issaquena County. This was the literary world that gave birth to Frank Stanford and gave him his sense of purpose and destiny.

When I read The Battlefield, I read it as Southern history, bearing witness to the region’s accursed past. This bastard son clearly struggled with the legacy of his uncertain place in a privileged lineage. In a letter to Dugan published in Hidden Water, Stanford describes his alter ego in The Battlefield: ”The character is endowed with the gift of second sight at birth. What would seem to most a blessing is, in fact, a curse. To expiate that curse, he sets out in a raft, alone and bound, and lets the river carry him where it may. He is constantly in pain.”

The pounding of your heart’s drum

Together with another one,

Didn’t you think anyone loved you?

— Lucinda Williams, “Sweet Old World”

Long before I ever heard Stanford’s name,

I grew up listening to “Sweet Old World,” the song Lucinda Williams—one of Frank’s lovers and the daughter of Fayetteville poet Miller Williams—wrote about his suicide. My mother loved the song, which she said reminded her of her brother, Robert, who shot himself when he was twenty-seven. As a girl, I would occasionally hear “Sweet Old World” being played somewhere in the house and I would walk into the kitchen and find my mother crying.

Stanford spent the last three weeks of his life in New Orleans with the poet Ralph Adamo and the writer Ellen Gilchrist. “Frank Stanford was my closest friend,” Gilchrist told me in an email. As Gilchrist’s biographer, Mary McCay, wrote, Stanford “may well have been the most influential person in her life.” In Gilchrist’s published journals, Falling Through Space, she describes Stanford as she saw him:

I knew a poet once and spent many days and nights with him and took walks with him and went into shops with him and watched the world with him and learned to adore the beauty of the world and despise its sadness. I must write of him someday and tell the world what it was like to know a great poet and be his friend. When he killed himself over some long-buried sadness, I could not bear to remember him and threw away all his books and all his letters and everything that had anything to do with him except an unpublished manuscript that was dedicated to me. It’s still around. Even in my sadness and rage I couldn’t throw that away.

Although he was little known beyond a small circle of writers who championed his work, and a growing number of young poets, he inspired great loyalty and admiration from everyone around him. Twenty years later, Gilchrist remembered him in his final days to the New Yorker’s Bill Buford, who was writing a profile of Lucinda Williams: “To know Frank then was to see how Jesus got his followers.”

On June 3, 1978, the day Frank Stanford left this sweet old world, two months shy of his thirtieth birthday, he flew back to Arkansas from New Orleans. When he got home, Stanford found his wife, Ginny, and his lover, C. D. Wright, waiting for him; they had spent the last several days together, unraveling his lies and his numerous affairs, and Ginny had filed for divorce. That night he retrieved the .22-caliber pistol he kept at his office, and later, at home, Stanford went into his bedroom and shot himself three times in the heart. The two women heard it. In her essay “Death in the Cool Evening,” titled after one of her husband’s poems, Ginny Stanford recalled the moment: “Frank fired three shots into his chest. Three pops, three cries. . . . I heard the crack and just as sharp I heard Frank hollering, ‘Oh’—surprised. . . . Pop Oh! Pop Oh! Pop Oh!” In the poem “Instead,” originally published in You, he writes:

Death is a good word.

It often returns

When it is very

Dark outside and hot,

Like a fisherman

Over the limit,

Without pain, sex,

Or melancholy.

Young as I am, I

Hold light for this boat.

Frank Stanford’s death was an act of passion. Or at least that’s how I’d always thought of it until this spring, when I read his will—handwritten on ruled notebook paper. It bears the date “Monday, 22nd May,” so it was composed in New Orleans, less than two weeks before his death. Nowhere on these four pages is the word “will” or anything so literal. Ginny Stanford attested, “The holographic will was brought to me by the deceased on the day of his death,” and she submitted it to the Washington County Probate Court. His handwriting was confirmed by three of his friends, including his former teacher James Whitehead. It comprises a list of things that he hoped would be taken care of following his death: funeral instructions, dedications for his unpublished works, even, on page one, what appears to be a side note—jazz to get, listing Pharoah Sanders’s 1977 album Pharoah, the John Vidacovich Trio, and Tony Dagradi’s (Stanford mistakenly writes “Eddie DeGrady”) Astral Project, all of whom he had presumably seen play in New Orleans at Jazz Fest. Stanford left the rights to all his works to his wife and Wright, seemingly aware that the two of them would be brought together by his death. “The only reason I’m doing this is so you both can have all rights to books—Both of you can have everything I have, and all rights to everything in future.” He leaves clear instructions as to what should happen to him after his death: “non religious burial, no family, no friends, cheapest place + cheapest way. Fayetteville.” Two pages later, he elaborates:

My mother, grandmother, sister, family—Ginny’s, Carolyn’s, mine—should not attend my burial. No ceremony. They are too dear and too old to take it. I love them.

I don’t even think it will be a good idea for you two to go—ANY Body, for that matter. No ceremony, just whatever it takes to make health regulation—As I heard them say, “You can’t even bury a dog these days, without hiring a lawyer!”

But there was a ceremony. And family and friends attended. Stanford was not buried in Fayetteville as requested, but in St. Benedict’s Cemetery at Subiaco, in the Ozark Mountains, where he attended high school. “We buried him barefoot in that kimono,” wrote Ginny Stanford. “The funeral home said no at first. They insisted he wear a suit and shoes. Claimed it was a state law.”

Tonight there is so much moon

I could write

You a letter

Instead I’m going

To leave

— “Blue Yodel of Just Another Gigolo”

Borges once discussed the metaphor of the moon as used in classical Persian poetry:

Let us look at the moon as a mirror of time. I think this is a very fine metaphor—first, because the idea of a mirror gives us the brightness and the fragility of the moon, and, second, because the idea of time makes us suddenly remember that that very clear moon we are looking at is very ancient, is full of poetry and mythology, is as old as time.

“The moon is with me always wherever I go,” Stanford wrote; it appears, in various guises, in much of his poetry. As I write this, a nearly full moon is high in the eastern sky, and the tide is coming in on Little Narragansett Bay at the mouth of Long Island Sound. This is the New England that I love—given to the natural rhythms of the sea—not the tidy walled-in gardens. A foghorn sounds its low baritone call and the bell buoys deliver their response. Latimer’s Light flickers in the distance. And though the night sky is now beneath the moon’s reign and the stars are faint, Venus and Jupiter are bright in the west behind me.

Poets, like the moon, are constantly changing. It’s our nature. And writing about Stanford’s work is like walking into the wilderness at night to try to capture a wild panther, a powerful hunter whose coat is the color of midnight. This creature is bigger and wilder than I, an animal not meant to be tamed. Frank Stanford’s poems are so full of the raw force of life that it is difficult for me to reconcile the circumstances of his death. His territory is the night, where secrets and lies can be hidden. “The poet is a liar who always speaks the truth,” wrote Jean Cocteau. And so my search ends as it began, with me beguiled.

What About This and Hidden Water, considered together with The Battlefield Where the Moon Says I Love You, give us Stanford’s body of work in one place, more or less, allowing us to explore his cosmos on our own. The night sky is vast and incomprehensible in its eternity. The stars that fill it are too distant to touch, but we can chart them and describe patterns to illuminate our myths.

Enjoy this story? Subscribe to the Oxford American.