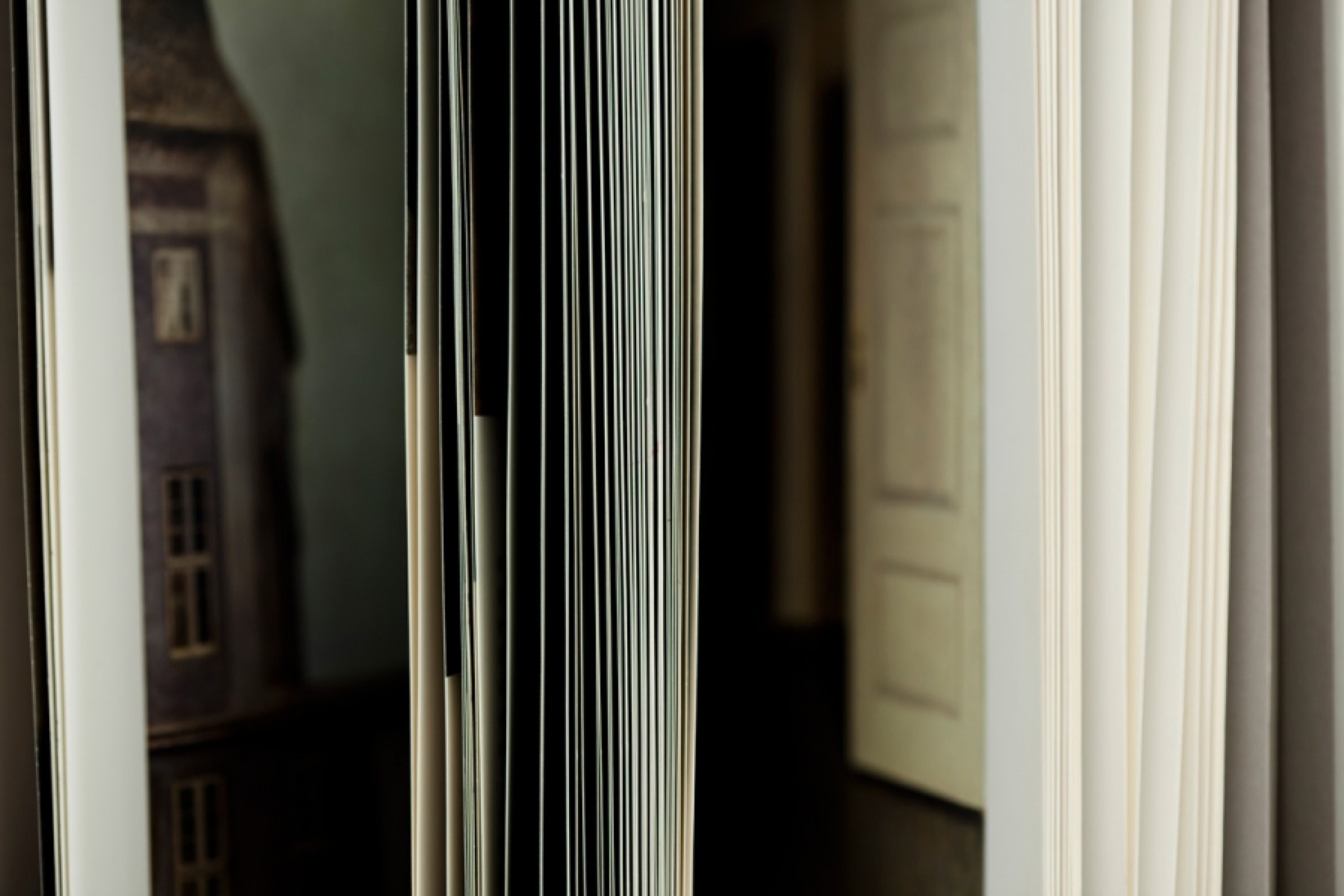

"Hammershøi," from the series "Reading Robert Wilson." Photograph by Mary Ellen Bartley. Courtesy of Yancey Richardson Gallery

Grotesk

By Evan James

Me trying to get from Iowa to Georgia, it wasn’t pretty. I’d been invited to spend the fall living and writing in the childhood home of Carson McCullers, which was lucky, because I didn’t really have a permanent home of my own just then: I’d been bouncing between artists’ cities and artists’ colonies, staying up all night drinking and talking with artists, and making art that no one would buy. I did have a gray 1989 Volvo with more than 300,000 miles on it—I can see it outside my window right now; a big tree branch fell on it last week, and left one side view mirror dangling by its wires—to which I already owed my miraculously safe passage from San Francisco to the Midwest. I took it to the shop for a last-minute checkup, crossed my fingers, and set out for the South.

This was late August. The Volvo’s air conditioning no longer worked, so I spent most of the first day’s drive with all the windows half-lowered, sweating as the grim stretch of Missouri that shoulders I-55 rolled by. Because the stereo in the Volvo no longer worked either, I’d picked up a boom box at a Goodwill before leaving, along with a copy of Bram Stoker’s Dracula on tape. In order to hear the British actor Alexander Spencer read Dracula over the roar of air coming through my windows, I had to turn the volume up as loud as it would go. If you happened to be standing in front of a Shell station outside St. Louis that day, you may have seen a sweaty thirty-year-old from the West Coast on his way to a dead Southern novelist’s house (“Now he looks queer,” you might have thought, “Should we beat him up?”), pulling in to pump some gas while a British voice reading the words of a nineteenth-century Irish writer blasted from a car of Swedish make:

“THE PHANTOM SHAPES, WHICH WERE BECOMING GRADUALLY MATERIALISED FROM THE MOONBEAMS, WERE THOSE THREE GHOSTLY WOMEN TO WHOM I WAS DOOMED. . . .”I spent that night in Memphis. I woke up early to get a cup of coffee downtown, and wound up in a shop full of police officers—eight or nine of them, all milling around with white paper cups in their hands. I approached the counter with some trepidation. “Don’t make any trouble now,” the barista called. “We’ve got the whole force in here!”

We laughed, and the whole force laughed with us. “This bodes well,” I thought.

Columbus, where Carson McCullers spent her childhood, sits just east of the Chattahoochee River, which also serves as a geographical border between Georgia and Alabama. In the kitchen of the McCullers house, my boom box picked up an Alabama public radio station; after writing all day, and before reading all night, I would listen to the radio and cook, in the very room from which warm meals once emerged to feed the girl who grew up to write The Heart Is a Lonely Hunter. I still haven’t read that book, though I meant to do so the whole time I was in Georgia. I had by then read The Ballad of the Sad Café, with its surprise wrestling-match betrayal at the hands of a formerly beloved dwarf, and Reflections in a Golden Eye, with its closeted army captain, hysterical army wives, and flaming Filipino houseboy. Protected first editions of these and other McCullers books sat in glass cabinets in the dining room. Promotional stills from film adaptations adorned the walls, such as one of a young Alan Arkin as the deaf-mute John Singer, deaf-mutely riding a carousel horse.

A letter came to the house shortly after I arrived, from the mayor of Columbus—Teresa Tomlinson, the city’s first female mayor. The letter welcomed me to town, then warned me that the food in Georgia could be a little fattening. The mayor also included a clipping about me from the local paper, the Ledger-Enquirer, in which my name appeared correctly in the body of the text, but as “James Evans” in the headline. This put a smile on my face. I’d never been written about in a newspaper before, and somehow the mistake made me happier than I would’ve been if they’d gotten it right. “This, too, bodes well,” I thought.

Writing aside, the primary gift of a residency is ample time half-free from the expectations of the world. The unexpected gift is that one may start, as a matter of course, to reciprocate the favor, relaxing one’s expectations of the world in turn. A name misspelled in the newspaper, a surprise interruption by two aging road trippers curious to see where Carson lived, or a rejection from a prospective literary agent saying that the heightened energy of your novel was somewhat overwhelming all become occasions not for annoyance or despair, but amusement, curiosity, cheerful drinking.

This was the frame of mind I soon found myself in, anyway, while tinkering with, as promised in my application letter and phone interview, another novel draft. There are only so many hours in the day I can bear this “working with spider webs,” as a novelist mentor once described the process to me; after that, I eat, clean, shop, talk. It was in carrying out these tasks that I tasted the magic elixir of life in Columbus. Almost every day I would walk to Publix, the closest supermarket. I’d discover along the way that many pedestrian sidewalks in town end without warning, which left me little choice but to walk in the road. In Publix, mothers would run into one another, and after a dance of decorous small talk, get down to gossiping in heavy Georgian accents:

“Oh, her? She goes to the doctor a lot. Always goin’ to the chiropractor.”

“Chiropractors! Now there’s someone who’ll always find somethin’ wrong with you.”

“And it’s usually somethin’ pretty creepy, if you ask me.”

“It doesn’t seem to be of much use, does it?”

“I sure doubt it. Though I did go once myself, when my head was misaligned.”

I’d be standing there with a packet of bacon in hand, trying to commit this conversation to memory. By the time I thought I had it, some new and noteworthy thing would happen. In this case, while paying for my groceries, my eyes went wide when the cashier, a middle-aged white woman, said to the tall, graying, light-skinned black man in overalls in line behind me, “Good afternoon, Mr. President.”

“You don’t know how often I get that,” said the man.

“Doesn’t he look like the president?” the cashier said to me.

The man who she thought looked like the president was grinning my way. He didn’t not look like the president, but the extent to which his face resembled that of Barack Obama’s was debatable enough to make the situation feel fraught. I was just about to respond with what I thought would be the best possible rejoinder—“Which one?”—when the dark-skinned young man putting my groceries into plastic bags said to me, “Look like who?”

“The president,” I said.

The young man laughed and shook his head, retreating back into the world of his well-protected private thoughts. Then the cashier held up a bottle of purple Vitamin Water I was buying. “Do you want this now?” she said. “Or are you going to drink it later, so that you can pour it over ice?”

And so I would walk back to Carson McCullers’s childhood home, a translucent green grocery bag hanging from each hand, mentally repeating to myself, “Misaligned head, Mr. President, Vitamin Water over ice . . . misaligned head, Mr. President, Vitamin Water over ice . . .” until I could sit down with my diary, and a glass of iced Vitamin Water, and record these details. Then Clarinet Corner would come on—a weekly public radio broadcast during which a man from Alabama and a visiting musician from Kraków, Poland, would talk excitedly about woodwinds—and I’d think, “But I just finished writing down everything that happened to me outside the house.” My keenest despair then was that some dazzling facet of daily life such as this would slip from the grasp of my memory, and that life would fast outpace the speed at which I could make happy note of it.

It’s harder to keep your thoughts in a philosophically amused, curious frame of mind when something actually unpleasant happens. As a preventive measure against the insane thinking that can come of too much artistic solitude and isolation, I started jogging around the track at Columbus High School in the mornings. What began as a habit driven by commendable sanity soon became one marked by derailing infatuation—what else is new?—when I found that my jogs overlapped with those of a woman and her extremely handsome personal trainer. Judging from his disinterest in my sideward glances at him and his revealing spandex, he was probably straight as could be. If I had been a closeted Army captain like Penderton in Reflections in a Golden Eye, I might have murdered him out of frustration when he snuck over to my house to sleep with my wife instead of me. Still, my desire to show this unavailable hunk how fit and well-adjusted I could be by running around the track and doing push-ups and lunges led me to overexert myself, and one evening, back at Carson McCullers’s childhood home, I threw my back out.

I lay on the carpeted floor of the basement apartment, looking at the desk where I wrote every day. I cursed it for having put me in the humiliating position of being so unfit for exercise that I could cripple myself with my own body weight. “So much for life with the personal trainer,” I thought, “though now I could use his expertise more than ever.”

Pain has a way of compounding any already present sense of being miserably alone in the world. Now I felt more like a character in a McCullers story every day—a lonely gay crushed between the magic of desire and the hell of unrequited lust, a living, breathing part of the so-called Southern Gothic, with its so-called grotesques. (The idea of the grotesque has its roots in High Renaissance Rome. Raphael, interested in ancient Roman ruins, had himself lowered by rope into the “grottoes” beneath the Trajan Baths—rooms, actually, that had been part of the domestic wing in Nero’s Golden House. The rooms were painted in a Pompeian style in which, according to the historian Daniel Boorstin, “fantastic forms of people and animals were intermingled with flowers, garlands, and arabesques into a symmetrical design.” Raphael imitated this style, which was called grottesche—“in the style of the grottoes”—when he painted the Vatican loggias. Boorstin continues: “‘Grotesk,’ William Aglionby’s English treatise on painting explained in 1686, ‘is properly the Painting that is found under the Ground in the Ruines of Rome.’”)

Rehabilitation came slow, aided by lame walks around the neighborhood. Passing one house, I recalled a neighbor with a good sense of humor who had come to the reception held for me at the house a few weeks before. He told me he had accidentally seen one of the previous writers-in-residence walking around the house in her underwear while he was smoking a cigar on his deck. “Hope you don’t make a habit of walking around in a similar state!” he joked. “Or is that just something all writers do?” I wanted to say that it kind of was. Then he told me I should get an air horn, so that if the house was ever being burglarized, I could sound it, and he would come over with his shotgun.

During these rehab walks I saw many lawns with one or more romney/ryan signs staked into them. The election was coming up. I didn’t want Mitt Romney to become president, not at all. I wanted the person who came to mind every time the cashier at Publix laid eyes on an older black man with greying hair to run our country. But I’d heard on the radio, from a voter demographic expert weighing in on the debates, that the most influential factors driving American voting habits remained race, religion, and marital status. So I was nervous, having read several frenzied public accusations that the Right had put campaign energy into discouraging people of color from voting in strategic places. Confused and discouraged voters during the presidential election seemed to be a pleasing prospect for some people. It was harder to be amused by the world at election time; I often turned off the TV in Carson McCullers’s childhood home, disgusted, in the middle of a debate or news of haywire voting machines, or a grotesque campaign pseudo-event.

But I still had the cookbook. I’d used my Chattahoochee Valley Libraries card—which I obtained by proudly showing my letter from the mayor to a librarian—to check out several books on Southern cooking. If I couldn’t lay hands on the hot personal trainer or bring myself to read The Heart Is a Lonely Hunter, I could at least leave Georgia having tried to learn how to cook a proper pot of greens. This I intended to do by consulting cookbooks, consulting Southerners, and making a total mess of the kitchen in Carson McCullers’s childhood home. Soon, however, I discovered that the library’s copy of Craig Claiborne’s Southern Cooking held something even better than recipes: another library patron, I assume a Southerner who felt very strongly about the ins and outs of their cuisine, had gone through the book and made many alterations, marginal arguments, and irate sentence-level edits. In one paragraph, for example, the phantom editor had crossed out “roux are” and written an emphatically underlined is. In the margin they’d written:

At the end of the paragraph, a penciled-in asterisk decorated the end of a line reading, “One of the most important ingredients in the preparation of a roux is self-confidence.” The asterisk led to a scrawled footnote: the words patience and practice stacked one on top of the other. In the recipe for Goldsboro Potato Salad, the editor had violently crossed out the brand name in a note about most of the barbecue restaurants in North Carolina using Hellmann’s mayonnaise.

“NO!” read the correction. “Duke’s!”

After I’d finished laughing, I shook my head. Now I was going to have to record this in my diary as well. And I’d have to do it while moving between my desk and the floor, depending on which one had become less painful for my back at any given moment. On the floor I might think, “The great Southern novelist Carson McCullers once walked over this floor.”

One of the guys from the English department at Columbus State gave me a painkiller on election night. My back was improving, but I took it anyway—there was so much more than just back pain to kill. A small group of Democrats from the university had gathered for what we imagined would be a long and bitter night of voter returns plagued by recounts. Then the results came in swiftly, with minimal drama. Good afternoon, Mr. President.

A couple of weeks later, the director of the McCullers Center held a delightful Thanksgiving dinner at her home. She surprised me by saying that her greens recipe used olive oil instead of ham hocks, smoked turkey legs, or some other meat product. I’d been cooking them with ham hocks, a joint of meat that had never crossed the threshold to my own childhood home, where the freezer regularly overflowed with salmon caught by my grandmother and her husband. I imagined the vigilante cookbook editor interjecting:

olive oil NO! Pig!

After the toast, we started in on stuffing, turkey, candied yams, mashed potatoes, gravy, green beans. One of the creative writing professors, who had sold me on HHhH, a French novel about the assassination of a Nazi leader, told me that two men in a neighboring county had been accused of trying to burn a predominantly black church on the night of Obama’s reelection. Immediately, in other words. Had they been standing by with oil-soaked rags and Bic lighters, watching the returns? Looking around the Thanksgiving table at our gathered group of humanities academics, poets, and emerging writers, I wondered what we would have been moved to burn if Romney had won. A golf course? Piles of the Book of Mormon? No, we wouldn’t have burned anything—we would have retreated to our separate corners with our copies of The Canterbury Tales or The Heart is a Lonely Hunter and maybe a nice glass of Riesling, or gone onto our preferred news websites and read postmortem commentary about the election.

Later I read in the Ledger-Enquirer that the men, thirty-seven and nineteen, burned the Christian flag and an old Bible inside the sanctuary, and tried to ignite pews and a communion table. The paper got their names right, and reported that their original bonds were set at around $137,000.

Nearly three months had passed. My time in Georgia was coming to an end. My back had benefited from an intense sports massage at the hands of a burly, ex-military lesbian who operated out of an otherwise abandoned-looking building in one of the complexes in Columbus’s commercial sprawl. Political signage had been pulled up from lawns, discarded along sidewalks, or left exactly where it was, signaling unbroken pride, fresh reproach, or lax housekeeping. My senses of wonder and curiosity revived now that, post-election, I expected and wanted less from the world. I would miss Carson McCullers’s childhood home, where I had done a great deal of writing, and pulled things up from the grottoes of my mind in solitude, and read many books, though not The Heart Is a Lonely Hunter.

Before I left, I met with a handful of students from the university in the conference room at the house. They ran a creative writing club, and wanted to have a Q&A session with me. They’d advertised the event as “Talking With Evan James,” which I liked, as it sounded like an intervention, or like they planned on disciplining or dumping me. (“We need to talk.”) The students, full of a love of literature, full of questions about books, grad school, how to make characters in fiction, and also how to make money, delighted me.

I did my best. I tried to drive home the importance of every individual honoring his or her own curiosities, and taking that which attracted his or her interest seriously. “We should be like Raphael, lowering himself on ropes down into the ‘grottoes’ beneath the Trajan Baths,” I would say, were it today. I tried to help them understand that writing might even be worth it, because at its best it rewarded curiosity richly, never mind what it was like at its worst, and to persuade them to drink from the elixir of life. (I didn’t actually say “the elixir of life.” I would have turned beet red, and proceeded to stammer incoherently, if the words had crossed my lips. I tried to suggest they drink from the elixir of life without saying so.)

One student asked me if I felt extra pressure living in Carson McCullers’s childhood home—pressure to perform under the spectral watch of a Great Writer. I thought for a moment, then said, “No, not at all.” I felt the pressure of being alive, the pressure to make something of my own daily America, which was filled to the brim with burning churches, thrown backs, broken Volvos, personal trainers, misaligned heads, sublimated erotic desires, salmon, Scandinavian crime fiction, students asking me whether I felt the pressure—do you feel the pressure? I felt like I might fail, but that if I did—and whether failure or success suited me better—would have little to do with Carson McCullers hanging over me like some phantom editor, pencil in hand, over Craig Claiborne’s Southern Cooking. If Carson McCullers wanted to put any pressure on me from beyond the grave, I doubt it would be critical pressure meant to shape my prose in the image of her own, or to compare my life trajectory with hers and find it wanting. (“I’d written three books by your age!”) No. I might find her quarters, painted as they are with fantastic forms, garlands, and arabesques, haunting in another way, true; she might, through them, press an asterisk into my mind as I observed and took happy note. The asterisk would lead to a footnote: the word “patience,” the word “practice,” one and the other, bodies fitted together, lovers kept alive on underground walls.

Enjoy this story? Subscribe to the Oxford American.