Hank's Dream

By John Lingan

Hank Deane walked out of Berry Field airport in Nashville and had to shield his eyes from the glare bouncing off Claude Hill’s Lincoln convertible. Deane was nineteen years old, wide-eyed and slight of frame, and he’d never been to Music City before, though June 22, 1974, was an excellent time to arrive. That very day, Waylon Jennings’s “This Time” hit No. 1 on the Country Singles chart, replacing Charlie Rich’s “I Don’t See Me in Your Eyes Anymore”—the outlaw and Nashville sounds were neck and neck, the audience only growing for both. But Hank didn’t have much use for either. He was in town to tap a deeper vein.

Earlier in the decade, a wave of traditionalists had cropped up—all acoustic, proudly backward-looking. Groups like J. D. Crowe and the New South, Old and in the Way, the Seldom Scene, and the Nitty Gritty Dirt Band reclaimed Flatt & Scruggs’s lightning tempos and Ralph Stanley’s rolling clawhammer banjo, added their own sense of hippie adventurousness, and arrived at a style that one of the era’s other major acts took for their own name: New Grass Revival.

No one embodied the genre’s ascension like the young Hank Deane. Three years earlier, he’d been an aspiring blues guitarist in the Philadelphia suburbs, so devoted that his father once drove him up to Queens so that Hank could live and study with Reverend Gary Davis for a weekend. He soon became a fixture at The Main Point, a famed Bryn Mawr coffeehouse and folk hub, and that’s where he first saw David Bromberg, session man for Dylan’s Self Portrait and New Morning and a hundred other things. In the liner notes for his first solo album, Bromberg thanked songwriter John Hartford for lending his band, and based only on that little hat-tip, Hank tracked down Hartford’s 1971 bluegrass record, Aereo-Plain, which Bromberg had produced. When Hank heard that album, it was as if his sputtering engine finally caught. Suddenly his life was in motion.

The Aereo-Plain band contained some of the era’s greatest roots-music talent. On dobro, playing with bouncy, acrobatic flair, was the veteran Tut Taylor. On lead guitar, flatpicking with unparalleled clarity and rhythmic drive, was Norman Blake, who had first met Hartford on The Johnny Cash Show, where Blake played in the house band. The hero of the group was Vassar Clements, the Florida-born fiddle player who had originated a style he deemed “hillbilly jazz.” On Hank’s favorite song, the breezy “Steamboat Whistle Blues,” and throughout Aereo-Plain, Clements’s fiddle is like that cartoon bluebird alighting on Uncle Remus’s finger—every time he plays, it’s a burst of otherworldly color, a clarion voice flying in to deliver you from your troubles.

Hank quickly became an acolyte of Hartford’s brand of beatnik pothead Appalachia. He traveled to the regional bluegrass happenings that were popping up all over, such as Indiana’s famed Bean Blossom Festival, and he got Blake, Clements, and Taylor booked at the Main Point. But that wasn’t nearly enough exposure for Hank, so he started making calls. Eventually, he managed to set up a gig at the Philadelphia Academy of Music, “a dream bill for bluegrass and country fanatics,” as the local Evening Bulletin described it. April 7, 1974: Hartford, Bromberg, Blake, Clements, Taylor, and the English bassist Dave Holland, late of Miles Davis’s Bitches Brew as well as Hartford’s Aereo-Plain follow-up, Morning Bugle. They filled all 3,000 seats and people were still lined up around the block. The show lasted more than three hours, with pristine sound by Elvis’s preferred road sound team at the time, the Clair Brothers. The audience swung from rapt attention to hysterical applause throughout the night. Everyone onstage made a small bundle of money, and Hank walked away with several grand of his own. Not bad for a night with his heroes.

The musicians were so energized by the experience that Hank received a standing invitation to make a record with the group in Nashville, using Aereo-Plain’s engineer, Claude Hill. He didn’t wait. Two months later he was on a plane, then found himself in the Tennessee sun, riding shotgun in Hill’s Lincoln, bound for Hound’s Ear Studio on Music Row and a session with newgrass royalty.

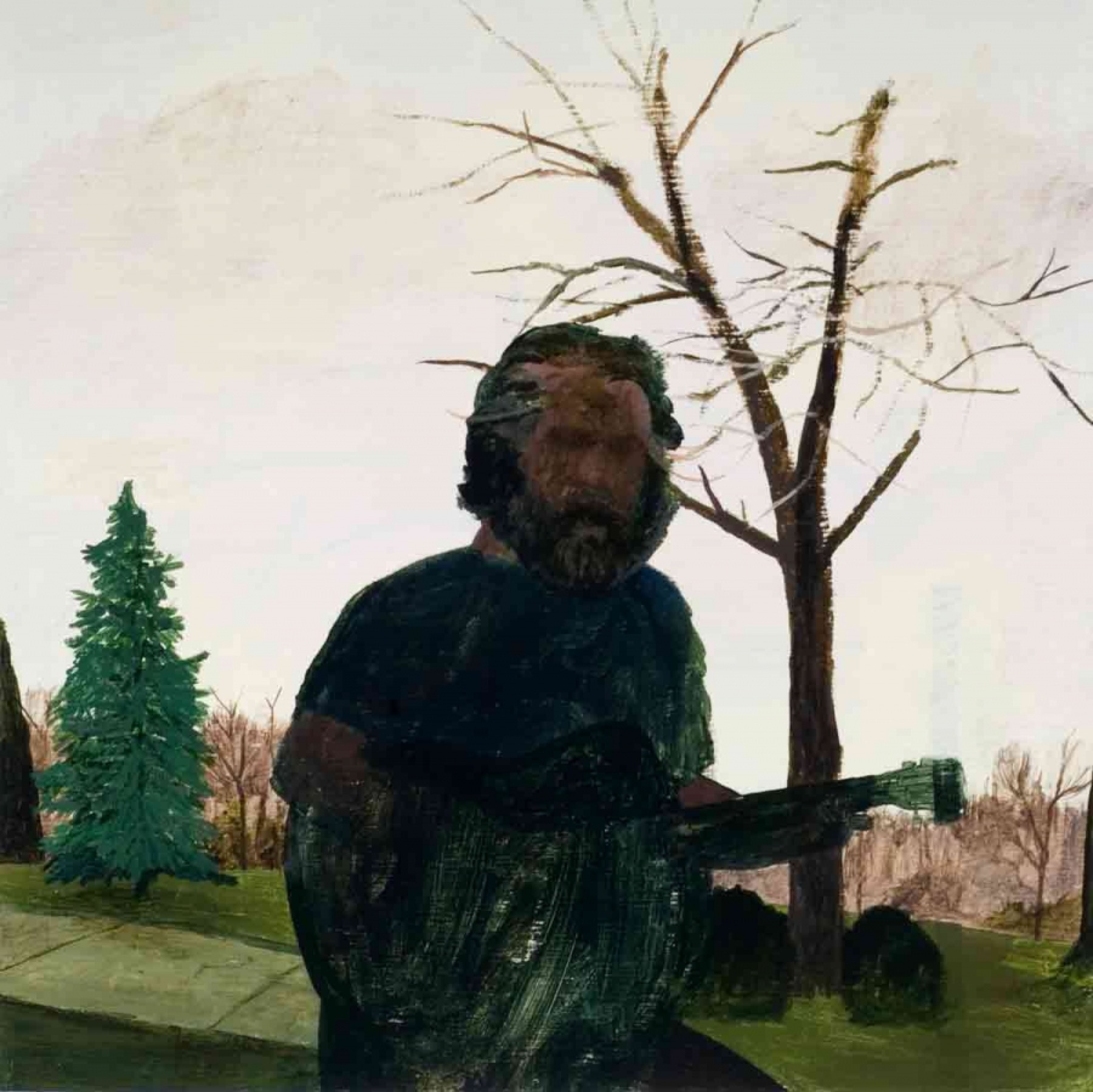

Hank Deane didn’t answer the door immediately when I went to meet him late last year. He’d warned me to knock hard since chances were he’d be playing his fiddle or his guitar inside, lost in a reverie. I banged a few times with my palm, peered in through the curtainless kitchen windows, and decided to walk up the small hill nearby to wait for him. For more than a decade, Hank has lived alone in a two-bedroom apartment above a barn near Unionville, about an hour west of Philadelphia and fifteen miles north of the Mason-Dixon line. It was a Saturday in November, and in the quiet of late afternoon I could hear only the soft chill wind and the carried conversation of two Spanish-speaking bricklayers working on the other end of the property. Then came the wild crack and echo of the landlord’s rifle as he took target practice from a spot near the farmhouse porch a couple hundred yards away. Then Hank’s door opened and he called out my name.

He looked youthful but weary: a smooth, leonine face framed by wispy hair and saucer-sized ears, his smile cocked off to one side like a shy teenager’s. But his shoulders were pulled in high, as if he’d been cold even indoors, and his brown eyes seemed tired. Rightfully so; Hank’s fifty-nine now, and five days a week he rises at 4:30 a.m. to check the Pennsylvania substitute teacher listings, signing up for whichever gig is closest. Sometimes it’s down the road, sometimes it’s an hour away. He loves the kids, and relishes playing some small positive role in their adolescence, a time he remembers well. But it’s a hard job, uncertain and not at all lucrative, and many days he comes home too exhausted to play the small collection of string instruments that he stores on the living room couch.

Inside, as we entered the kitchen, I noticed a cardboard box full of shrink-wrapped CDs on the floor, representing the only commercially available copies of the record that Hank produced as a music-drunk teenager in Nashville forty years prior. It was named, simply, for its seven legendary session men: Norman Blake/Tut Taylor/Sam Bush/Butch Robins/Vassar Clements/David Holland/Jethro Burns, though Hank refers to it as “The HDS Session,” after the label he created to release it. He took his initials, added an S to sound professional (“like CBS Records”), and randomly listed the album as HDS—701 when it came out in September 1975, distributed by Flying Fish Records, the label that released Aereo-Plain. There was never to be an HDS—702. And in fact, The HDS Session, though popular, went out of print surprisingly quickly. Hank, lifelong owner of the album rights and the session tapes themselves, had it digitally remastered in 2004 and sold the CD himself. That went out of print, too, and I only learned of it after my own Aereo-Plain obsession led me to a lone track on YouTube, which has since been removed. Last summer, I contacted Hank to find out why it was so hard to get a copy of such a unique record—one of the newgrass genre’s most talent-heavy and adventurous documents. He was proud of the sudden attention, which was enough to compel him to press a few hundred more CDs, which you can find on Amazon right now for $17.98 plus shipping. As of November, when I visited, he’d sold a few dozen.

I was eager to listen to the album with Hank, but he proposed that we take a stroll. He grabbed his knit hat and we set off down the graveled main drive and turned right, farmland stretching out on either side. “I love this walk,” he said, breathing in deeply. Every passing truck stopped so neighbors could say hello to him. He was friendly and attentive to everyone, though we quickly pressed onward so he could tell me everything he needed to say about the afternoon that was, by his own repeated admission, the high point of his life.

“Everybody was at the very top of their abilities. Nobody was sick yet. Later on there’d be cancer,” he told me. “But on that Saturday everybody was feeling good, and everybody had prepared for it. They came in loaded for bear. All these miracles were happening. It was a perfect day. The sun was shining, and it was amazing.”

Unable to embed Rapid1Pixelout audio player. Please double check that: 1)You have the latest version of Adobe Flash Player. 2)This web page does not have any fatal Javascript errors. 3)The audio-player.js file of Rapid1Pixelout has been included.

Listen to “Sauerkraut 'N Solar Energy” by Norman Blake, Tut Taylor, Sam Bush, Butch Robins, Vassar Clements, David Holland & Jethro Burns

On an album of ambitious, genre-blending acoustic music, the second track, “Sauerkraut ‘N Solar Energy,” stands out in both name and aspect. The bouncy blues was composed on the spot, based on an idea that had come to Hank in a dream. The band followed his lead. “I said, ‘It starts with Dave and then everyone comes in, then everyone drops out and Dave brings it back double-time,’” he told me. “And they did it in one take! It was brilliant!” Such was the confidence, cohesion, and spirit of spontaneity in the room that day, which began a little after 2 P.M., an early session by musicians’ standards.

Norman Blake showed up first, with a battered guitar case and his new girlfriend, Nancy. A quiet man from Sulphur Springs, Georgia, Blake had been playing music professionally since 1954, when he dropped out of school at sixteen. He’d played the Tennessee Barndance, a famed regional radio program, then was stationed at the Panama Canal, where he led a bluegrass trio. When he returned home he played guitar for hire before joining June Carter’s road band, and it was a short jump to her husband’s TV show. By the early Seventies, he’d hooked up with John Hartford and made a couple solo albums. By 1974, Norman Blake had one of the most graceful and powerful right wrists in all of American guitar playing.

Dave Holland had traveled down with his wife from their home in upstate New York. It was their first road trip through the Deep South, and they’d done it leisurely, stopping at every chance and marveling at everyone’s hospitality and openness. By the time they reached Nashville, Holland was beatific, amazed that his bass playing had taken him from the postwar English Midlands to the swirl of Miles Davis’s most boundary-defying period, and now to a Nashville session with some of the greatest American roots players alive.

Hartford had disinvited himself, for reasons nobody knew. And Sam Bush had invited his idol, Jethro Burns, of the legendary duo Homer & Jethro, and the New Grass Revival guitarist Butch Robins. Along with Vassar Clements, who arrived midway through the afternoon after playing a gig, and Tut Taylor, there were seven men who shared a broad knowledge of “old-time” music, but few singers or songwriters among them. The common thread, highlighted by the unexpected addition of a jazz bassist, was improvisation: more than anything, each man in Hound’s Ear Studio was a master at pulling a melody out of the air.

With that in mind, the music quickly spiraled away from strict country. They tore through the first couple songs, “Sweet Georgia Brown,” the old ragtime standard best known as the Harlem Globetrotters theme, and “Going Home,” featuring a melody lifted from Dvorak’s New World Symphony. Blake recorded an astonishingly fleet-fingered solo piece, “The Old Brown Case,” that pushed and pulled at different time signatures. Tut Taylor offered up “Oconee,” named for the river near his childhood home in Georgia, which the group worked up into a minor-key cross between a Spaghetti Western soundtrack and a gypsy march.

“They all seemed together by ear,” according to Nancy Blake, who later became Norman’s wife and longtime musical partner. She was in Hound’s Ear purely as a spectator that day. “It was the first time I’d ever seen hillbilly string musicians hit that Charles Mingus headspace. I knew there was music coming into the world that had never been in it before.”

Saturday afternoon in nashville.

me and norman and all the rest of them gathered together in hound’s ear studio and played music. we are here because of our shared desire to record together. spontaneous and free!

Hank’s original liner notes, written afterward in Philadelphia, are beautifully youthful and autobiographical. Even though he wouldn’t dare pick up an instrument among such a rarefied crew, his fingerprints were all over the record. He’d insisted that the album’s title and cover mimic the spare, clean-line look of ECM Records, the progressive German jazz label. And the final song, “Vassar & Dave,” a blues duet improv featuring his favorite players, Holland and Clements, was his idea. “A bass and a fiddle—that kind of thing had never happened anywhere,” he said.

So when The HDS Session came out, it belonged as much to Hank as any of the men on the cover. It was his excitement that had led to such a generation-spanning supergroup, many of whom had not recorded together before or since. It was Hank who gave them ideas and song titles and eventually doled out their royalties. And while it was just another session, albeit a memorable one, for these veteran players, it was something more powerful for Hank.

“It gave me a sense of immortality, and freedom,” he told me on our walk. It was as if “all of the good that I was experiencing was permanent—no one could destroy it. I wouldn’t have to worry about death or dying. I was overwhelmed by it.”

The record was a musical success and a seemingly popular one as well, though the checks that Flying Fish sent didn’t reflect the excitement that audiences showed the musicians during the concerts of the time. And proud as he was that his album turned out so well, Hank didn’t have any designs on a further career. As Dave Holland, who remains close with Hank, told me, “He’s kind of an innocent in a certain way. He doesn’t have a grand plan. He’s going through life and learning what he can.”

On Holland’s recommendation, Hank enrolled at the New England Conservatory in the early Eighties to study the upright bass. “I was not a wunderkind,” he explained to me. “I could listen to something and learn to play it, but I could never improvise like Dave does.” Nevertheless, he earned his degree and then took a series of short-lived jobs: piano tuner, gas station attendant, car wash employee. He played music along the way, leading a jazz trio as a guitarist and opening for touring acts at Philadelphia’s Chestnut Cabaret. And he produced two subsequent albums—one in 1985 featuring Hartford, Holland, and Vassar Clements, and another a few years later with Clements, Holland, and the jazz legends John Abercrombie and Jimmy Cobb. But his love for music never quite cohered into a career, and soon enough the decades passed, visiting upon Hank his share of the universe’s troubles and sadness—his supportive parents died, he saw romance come and go, his heroes and friends succumbed to old age and sickness, and he had health scares of his own.

As the sun fell, he grew philosophical, sharing the kinds of thoughts that come to people as they stare at a screen at 4:30 A.M., hoping the day’s work will appear. “People eat and they reproduce and they raise the children, and you spend all your time getting the money to put the food down your throat. And it’s pretty fucking monotonous. And the whole economic system and society we’ve got in place, it drives you right into the ground.” His voice rose, and he paused to calm down. “I didn’t understand this growing up, because I was protected. I’m finding it out now.”

Certain record labels have expressed an interest in giving The HDS Session a proper reissue, maybe even releasing the Philadelphia concert as well. Hank has the tapes to do all of it, and such an arrangement might help him put a dent in the debt he’s accrued. But it’s hard to trust a record company to do honor to your legacy, your most precious memories. So for now it’s only available by mail, direct from a barn in Unionville, Pennsylvania. Hank still sends royalties, even if only a few cents, to every living musician on the record. He has control over this one tiny corner of the world, and he is devoted to proper stewardship of it.

Back in his living room, darkness falling outside, Hank ran a finger over a hardcover set of Van Gogh’s complete works. “I tried to fit in but I never did,” he reflected. “I always ran to music. I spent most of my time with music, trying to learn to play the guitar, trying to learn to play the fiddle, and loving every minute.” Hank continued, and we talked about his life after the record, his family, but he kept coming back to the music. “If you weren’t here I’d be playing.”

A little before midnight, the group convened in the Hound’s Ear control room to listen back to the day’s best takes. The mood was high; the musicians picked through each other’s cases and admired each other’s instruments, especially Dave Holland’s shockingly valuable upright bass and Jethro Burns’s red Florentine-style mandolin. But when the recordings played, silence descended on the room. They’d all agreed that the session had gone well, but the music was even fuller and wilder than they’d experienced around the microphones. In Nancy Blake’s words, “There wasn’t a lot of yeah-yeah.”

Outside, everyone had a hug for Hank Deane, who suddenly stood among his heroes as an equal. They sung the day’s praises a while longer, then scattered into the Nashville night. Hank had learned what life could be, and he skipped down 17th Avenue with a line from e.e. cummings in mind, something Holland had shown him earlier that day: “Miracles are to come. With you I leave a remembrance of miracles.” He was nineteen years old. He loved music. He couldn’t imagine a better friend.

Enjoy this story? Subscribe to the Oxford American.