Guy Davenport and Unidentified Woman in Darkened Room, Looking Through Doorway (1966), photograph by Ralph Eugene Meatyard © The Estate of Ralph Eugene Meatyard, courtesy Fraenkel Gallery, San Francisco © The Metropolitan Museum of Art. Image source: Art Resource, NY

Coming Up with Guy Davenport

By Brian Blanchfield

A long-ago letter, a lifelong fascination, a longing appreciation

Guy Davenport died the same week as Susan Sontag, a few days on either side of New Year’s Day, 2005, and since there isn’t evidence to suspect that either thought much or often about the other, and their social milieus were certainly nowhere overlapped (she was from the start an icon of hip intelligentsia, her cool charisma only enhanced when slowed to three-quarter speed for Warhol’s Screen Test camera; he rarely traveled from his home of Lexington, Kentucky), that may seem a capricious point. Except that they, of the country’s preeminent literary commentators, were the two who deemed themselves literary writers foremost and—whatever readers decided—critics only secondarily. True, too, especially of the pair, that their criticism was adventurously global and also recuperative. (Which of the two extolled to American readers the value of Robert Walser or W. G. Sebald or Marina Tsvetaeva or David Jones or Antonin Artaud or Victor Shklovsky or Roland Barthes would be hard to keep straight.) But I think the particular cultural loss that was doubled that week was the loss to independent intellection; for years afterward you’d be hard-pressed to suggest any surviving American their match in essaying, in tunneling associatively among epochs and disciplines (mocking in their example such a word, disciples never to any one field), anathema to the niche specialties of academics, those whom Davenport defined as training a “fanatical narrowness of mind.” He was a modernist scholar, one of the earliest, and for decades a leading translator of ancient Greek poetry; but he also wrote with authority on the social history of the pear, Mother Ann Lee and Shaker aesthetics, Dogon cosmogony, the anthropology of table manners, 2 Timothy and the Pauline doctrine, Louis Agassiz, Eudora Welty, geodesic domes, the paintings of Balthus, and the behavior of wasps—which he fed in his home from a saucer of sugar water. He himself subsisted on fried bologna sandwiches and Marlboros.

I’ve been immersed in his work for the first time in a decade, relishing the unpredictable polymath and maker in him (painting, drawing, and collage were very much part of his practice), alive to the many recurrences—the discovery of which becomes a kind of intimacy—across the thirteen books of his I own, and thinking hard about whether he and his approaches would be more or even less at home in the world twelve years after his death. He was thoroughly an original, whose agile resourcefulness was like Sir Thomas Browne’s, antithetical to consensus Wiki-knowledge, and whose books are unlikely ever again to be taught in classrooms, however inoculative a trigger warning might be: “stirring, graphic description of thirteen- and fifteen-year-old boys and sometimes girls in recombinatory sexual coupling; be advised.” As with the shepherds in Theocritus or the boys of Bel Ami, Guy Davenport in his longer stories conceived utopian communities he populated with youths discovering pleasure, wherein a bachelor lecturer or a slurry old Diogenes might amble and expostulate to his distracted auditors. “It has the spiritual clarity of beginnings.” Nice line, right? Now imagine retweeting it, knowing the narrator is referring to (hashtag) Greek gymnasia where pubescent boys wrestle naked. It’s easy to send up such an original; harder to imagine how to come up with one so disinhibited now, so insistently innocent of popular mores.

In one of his best writings—a work of short fiction with characteristic elements of essay—Davenport casts as his hero early twentieth-century Swiss writer Robert Walser, the surreptitiously prolific genius who resorted in his midlife poverty to working as a butler in a countryside schloss, a man admirable for what he terms his “kithless epistemology.” Once the two halves of the term flicker into recognition, it raises the question: how does one know what one has come to know without kith, without associates or colleagues or comrades? Presumably it would be by discovering things on one’s own, by exploring and observing and testing empirically, by reading off-syllabus, pursuing one’s own leads. A whole vocabulary of phrases for peerless autodidacts builds in Guy Davenport; in one of his essays—with elements of storytelling—he relays the physicist Ernst Mach’s comment about Einstein, that he was “a uniquely individuated mind.” It’s clear in the retelling that this registers as highest praise. To be highly differentiated—until a sort of singularity is achieved—is, if not an end in itself, fair evidence of good, free, lifelong idiosyncratic investigation. Eventually you are unlike even your ilk. Does that (still) sound ideal? If it at least sounds admirable, you might be a reader of Guy Davenport. The whole sixteen-book body of prose that Davenport left can be seen as a reclamation of writers and artists and philosophers whose creative thinking was undeterred by the prevailing knowledge of their eras, “minds of this sort that backtrack to the archaic” to build anew instead. The title story of the first of those books, Tatlin!, opens on one, the forgotten Russian artist Vladimir Tatlin, exhibiting in 1932 his ornithopter glider with wings, an “air bicycle,” which—with no use for Kitty Hawk or the decades thereafter of incremental advances in airplane technology—he has developed from Da Vinci’s original notated sketches, and from direct observation of the ossature of herons, especially their high elbow joints. In Davenport you have the sense that to know what everyone else knows is good preparation primarily for being indistinct. The kind of flight designed to privilege intuition, to entrust operations to the body, is necessarily solo flight. So much for kith.

As for kin, I think the wry remark he makes about Kentucky photographer Ralph Eugene Meatyard’s origins might be a mirror: “he had invented himself, with his family’s full cooperation.”

Guy Davenport was born in Anderson, South Carolina, in 1927, midway along the southern Piedmont crescent, and despite growing up in a home and environment without readers, was deeply absorptive in books that chanced to circulate there. From Edgar Rice Burroughs’s Tarzan books (given to him by the mother of a man named Clyde, who wouldn’t need them while he was “in the penitencher”) and secondhand book-of-the-month biographies of Ben Franklin and Da Vinci, he came to seek writers “whose style, I was learning to see, was an indication that what they had to say was worth knowing,” recalling in “On Reading,” the best literacy autobiography I know, that he read both volumes of Charles Doughty’s 1,200-page Travels in Arabia Deserta under his family’s fig tree one summer. After quitting high school early, he enrolled at Duke and then Oxford, where he wrote the first thesis there on James Joyce, and was called up by the Army twice for duty in field artillery and paratrooper divisions before completing his doctorate at Harvard, where his dissertation became an early important book on Ezra Pound’s Cantos. For his development into an innovative translator who might more aptly be called coauthor (annotating time’s tears in the papyri) of the fragmentary lyrics of Archilochos and Sappho, and into a late-modernist writer and scholar worthy of awards from the MacArthur Foundation and the National Book Critics Circle, Davenport credits not only the reading he taught himself, but also another determinative practice of his childhood. Every Sunday, after Baptist church, without telling the aristocratic grandparents whom it would have scandalized, he and his family would go “looking for Indian arrows” in Upper Savannah Valley towns south and west of Anderson. Less private than the geography of the imagination that built up his world while he read, this foraging nonetheless held space for the solitary; central to it was “the sense of going out together but with each of us acting alone. You never look for Indian arrowheads in pairs. You fan out. But you shout your discoveries and comments . . . across fields.” Of his family’s avocation, locally notable enough that visitors from the Smithsonian were directed to their collection, he puzzles out a telling autoethnographic study, “Finding.” “I was with grown-ups, so it wasn’t play. There was no lecture, so it wasn’t school. All effort was willing, so it wasn’t work. No ideal compelled us, so it wasn’t idealism or worship or philosophy. . . . Yet it was the seeding of all sorts of things, of scholarship, of a stoic sense of pleasure. . . . I know that my sense of place, of occasion, even of doing anything at all, was shaped by those afternoons. It took a while for me to realize that people can grow up without being taught to see, to search surfaces for all the details, to check out a whole landscape for what it has to offer.” “Finding” is also a poetics.

“Searching surfaces for all the details” is certainly the method of Davenport’s most famous essay, the title piece in his first collection, The Geography of the Imagination, which concludes with a startlingly comprehensive semiotic reading of Grant Wood’s iconic painting American Gothic, figure by figure, item by culturally legible item, panning across the canvas, deriving each material or ideological import to the frontier imagination. From the seven trees distributed laterally about the A-frame (“as along the porch of Solomon’s temple”) to the bamboo sunscreen (“out of China by way of Sears Roebuck”) that rolls up (“nautical technology applied to the prairie”) to the buttonholes and spectacles worn in the painting (thirteenth-century facilitations of the modern) to the very pose that Wood’s sister and dentist assume, modeling as a homesteading couple (“a pose dictated by the Brownie box camera, close together in front of their house”), the essayist unpacks the painting’s freight, the Greco-Roman and Northern-Western European content complicating the American self-mythology of uproot and make-do. About the Iowa farm-wife figure herself Davenport sharpens his focus: “she has the hair-do of a medieval Madonna, a Reformation collar, a Greek cameo, a nineteenth-century pinafore. Martin Luther put her a step behind her husband; John Knox squared her shoulders; the stock-market crash of 1929 put that look in her eyes.” Davenport reads still lifes equally well, deep-mapping, balancing their symmetries and reading across their axes, and from a table setting can even savor a bit of one-hundred-fifty-year-old gossip: Cézanne was declaring in his apples that he had overcome a betrayal by his former classmate Émile Zola, who once, before turning on him, had presented him a basket of the fruit that Corydon gives his lover Alexis as overture in the Virgil eclogue they knew well. Too, Van Gogh’s onions resting on F. V. Raspail’s early home-health manual was a message, in recovery still from severing his ear, to Gauguin, whose decadent carousing had disgusted him during their falling out. Inside Raspail, we are told, were recommendations of a camphor smear to forfend wet dreams, putatively to reserve potency, and of onions, a nutrient nearly Calvinist, revolutionary in its affordability.

It was about this work on still lifes, Objects on a Table, that I wrote a fan letter to Davenport, in December 2000. I failed to tell him in the letter what might have interested him more than the regional fellowship I strained for—my hometown ninety minutes northeast of his—or the poems I forced on him: Objects was the book I had asked a cute bookstore clerk named Douglas to help me find. When we started dating—we were together four years—Douglas discovered I already owned the book, which I’d said in the store I’d wait to buy in paperback, a feint. What is it about myself I’d wanted, with the book, to see if Douglas would match? When Davenport’s uncareful and kind reply came, in part the news was Davenport did not identify with me. The poems were not to his taste—the page-long letter written on consecutive early January days begins, “The problem may be that you’re 27 and I’m 72” and concludes, “but you’re a real poet. I wish you luck getting into print.”

And it was my rediscovery of the lost letter this year, during a move with my partner, John, from one part of Tucson to another, that rekindled my interest. After rereading the first four books (as if for the first time) I told my friend Sharon—who once overheard no less a sexual utopian independent thinker than Samuel Delany claim Davenport as a hero—that I ought to have moved to Lexington while, when I received that letter, I still looked like one of the slender boys in their briefs that Davenport draws in his best book, Da Vinci’s Bicycle, in headstand, even hanging from monkey bars, shirts riding up in folds you could find in Dürer, and offered myself as ardent ephebe, to learn Latin and Greek, to learn learning. I am jealous of his executor, Erik Reece, who writes the poignant afterword in The Guy Davenport Reader, who was his Comp Lit student at Kentucky and became his friend amid whatever rumors it produced that the “pederast” had finally found a willing youth. I believe it is in Reece’s reminiscence I learned that Davenport’s beloved life partner, Bonnie Jean, lived six doors down; that as a kind of tactile meditation he painted grids laboriously with a tiny brush (and when he drew he used a crow’s quill he filled with ink); that he built his own desk, in the center of what would otherwise be the dining room; that he shared fried bologna sandwiches with Erik sometimes right over the pan; that he answered every letter, keeping up with nearly two hundred correspondents at any given time, telling many of them, including myself, that he had, “at rough estimate, about eighteen readers.” He told the Paris Review that he learned an immense amount from letters he received and recorded what came and went in a logbook he mined for his writing.

“Islanders study the newspaper carefuller than most.” Today that’s my favorite sentence in Davenport’s fiction, which—whatever may be the case for Sontag—is better, yes, than his essays even. It’s a remark that follows some exposition a narrator provides, about the man he watches coming ashore in Guernsey: he has traveled from Belgium, where he, and Edgar Quinet and Doctor Raspail (one of those recurrences I note tenderly), had been in political exile from Louis-Napoléon’s France. The story is called “John Charles Tapner,” the name of a prisoner put to death in Guernsey; the narrator is the island’s provost to Queen Victoria; and the arrival was, we come at last to learn, Victor Hugo’s. Hugo had come in protest of capital punishment. The year, 1855, is not mentioned, nor that he stayed and wrote Les Misérables and the other great works of his final years there.

He came across the brown sand, enlarged by the mist that had bedeviled the island for days, a hank of vraic around one boot, he never minding the hamp of it, his grizzard beard runched out from the lappets of his redingote. The bonnet and frogged cape behind him was his wife, fashed and tottering, flapping like a sea mew. And yet another fluster of ruffles, wet and squealing gaily, was his daughter.

—A very Beethoven of a wind! he cried into my ear.

The influence of Joyce in this sodden stormy passage is perhaps clear. As I type, Microsoft Word is suspicious of the words vraic, hamp, grizzard, runched, and fashed, which must mean lappets and redingote are in the dictionary—yes, a “decorative flap or loose fold on a garment” and a French alteration of “riding coat,” respectively. More to the point, the language here is appurtenant to the Channel Island setting—not a Latinate word in the lot. Hamp is Anglo-Saxon in its wet brevity, ready for British understatement of hardship. An astute critic, the Belgian artist Alain Arias-Misson once noted that Davenport’s was a “fiction of nouns,” by which he meant not that we should discount the adjectival, heavily participial sizzle of prose the likes of this in the excerpt but, rather, that “objecthood, this substantiality of Davenport’s writing, is everywhere apparent . . . while most contemporary writing is all verb, event as verb not noun, collecting no moss of existence, pure transiency.” It’s true of “John Charles Tapner,” which spends its chief predicate at the start of this early paragraph: Victor Hugo came to Guernsey, to inquire into the conditions of Tapner’s life and death. That’s what happens in the story, which is mostly camerawork, touring alongside the foreign eminence and the local bailiff the rainy streets, registering the “forty greens” in this “Polynesia with frost and fog,” and pacing off penal protocol in the bailiwick. Alternating with that one is another tour, more memorable, around the narrator’s dinner table, alighting on hearsay about Hugo, locals finding scandal in his son’s “turning all of the plays of Shakespeare into French” and their acting them out in the evenings—“Grown people!”—and finding insult to Her Majesty in the republican’s open letters reprinted in newspapers. (It is quintessential Davenport that he embeds not in their conversation nor anywhere in the story, but rather in another book, another genre, in an essay on Montaigne, actually, the information that Hugo’s favorite dog was named Senate.)

The telling local reception of a rare outlander, at a historic juncture of cultural encounter, shapes a number of Davenport’s stories, including my favorite, “The Trees of Lystra,” the opening story in his third collection, 1981’s Eclogues. It’s told by a young adolescent resident of the first-century Greek village. Again there is a kitchen table late in the story where a family gossips about the news of the day—traveling religious philosopher Paul and his companion Barnabus have come to Lystra, as to Philippi and Corinth, to preach the monotheism of Christianity, to inveigh against “superstitions” and the worship of multiple gods, and are, irony of ironies, misrecognized as Zeus and Hermes, taken in by older villagers who have no other prior context for the miracles Paul proclaims but who are familiar with the disguises of gods who test mortals’ hospitality. The narrator may be biblical Timothy, who, history shows, followed the apostle from Lystra—though the story ends with the missionaries being stoned, retreating in a rush. Davenport has more to say, in a terrific late essay, “II Timothy,” expressly that Paul tragically misconceives “the descent of the dove,” Jesus’s return, as an event in historical time and his message of unity as one of divine Unitarianism: “Early Christianity was . . . in the midst of a thousand altars to generous gods, a belief in whom was thoroughly rational. . . . What perversity in Christianity balked at tolerating them until they, as indeed happened, could be absorbed into [its] mythos.” A thought experiment recurs in Davenport, one that I inferred before I fully understood: we are permitted to imagine an alternative history in which Christianity and premodern paganism are reconciled or undivided. “In Eclogues I bind the double tradition of Greek and Roman pastoral to the pastoral metaphor in the gospels. I make a story out of Acts 14:6–20, where Ovid’s account of Baucis and Philemon coincides with Paul and Barnabas in Lystra, an event that Paul reminds Timothy of in his second letter to him. . . . Paul’s relationship with Timothy is the pattern for most of the relationships in Eclogues: teacher and fond pupil, mature and young shepherd.”

The best work of the very good (and still the only) monograph study of the author, Guy Davenport: Postmodern and After by Andre Furlani—an Italian scholar who teaches in French at Concordia in Montreal (Europeans have largely been Davenport’s more serious readers)—is its analysis of Davenport’s fiction as pastoral. Really it’s some of the best writing anywhere on the pastoral, as a classical genre and a disposition. Of its attributes, he writes, “Primary is a postlapsarian disposition, ethical and reformist, toward the prelapsarian. Hence the highly cultured praise of the primitive, the idealization of autarchic modes of social organization, and the appeal to erotic license. . . . Like that of Virgil, Davenport’s Arcadia belongs as much to fantasy as to geography.” But in comparing Davenport’s stories—in Eclogues, and elsewhere—to the originary models in Virgil and Theocritus, he overlooks a key borrowing, one that I think best unites those two unlikely operative terms postmodern and pastoral. Yes, the amative shepherds, horny as Pan in places, who speak or sing the idylls and eclogues in Classical lyric poetry are Davenport’s essentially, and, yes, bucolic as a descriptor derives from these shepherded poems which standardize a kind of soft-grassed perfect hillside place from which to speak, and Davenport requires paradises too; but the poems the shepherds deliver, many of them, in Virgil and Theocritus, do a particular thing, a Classic thing: they isolate bits of well-known myth, dilating a detail of a larger story, narrating it and often setting it within the very tableau that is their surrounding landscape. Herakles running along the banks of the river looking for his lover Hylas, whom water nymphs have drowned, is the matter of an idyll, told as the flock grazes. This is the method of the majority of Davenport’s stories: they zero in on a detail—in his case not from myth but from history—to lift out and amplify and elaborate inventively an incident from the recorded annals, to walk the native ground of that event and look around for glinting particulars, imagined and documented alike. The eye roves the area as the epochal sweep of history moves through. “The Aeroplanes at Brescia” retells and enlarges a published account by Franz Kafka, traveling on holiday in Italy with his friends Max and Otto Brod to an early air expo (half of the flight demonstrations fail), which proves a kind of nexus of history, late summer 1909; there the bouncing ball of narrative attention finds a young man with an intense gaze whom Kafka learns is Ludwig Wittgenstein, and the Countess Bonaparte, Puccini, maybe Marinetti in the crowd, plus rumors of “the three Bourbon princesses.” Does the “profile of a lady with a perfect chin and gentian eyes . . . blocked from view by the top hat of a gentleman in bassets” belong to Gertrude Stein? It is one of Davenport’s more nounish stories, a profuse survey of personages under the propeller sputter and indifferent buzz of progress. Liftoff of the first military air campaigns would be soon, the postlapsarian understands. In the same book, directly thereafter in fact, “Robot” follows a dog so named, or follows several French boys following their dog, who, following a rabbit, has fallen into a softened limestone sink, unsealing at once the cave at Lascaux. We are local then to the discovery in September 1940 of the now-iconic Paleolithic murals of horses and bison, seeing them first from the eyes of these kids who had been establishing in the woods a clubhouse or a militia—hard to tell—within earshot in any case of the bumper-to-bumper French traffic fleeing the approaching Nazis. Innocence and freedom and happenstance and fate are, characteristically, players in the Davenport pastoral. In the middle of the story, the simplest question is asked of the old abbot who has come to interpret the finding, a question that likewise drops us into what runs under the story, “What are these caves?”

—Arks for the spirits of animals, I think. The brain is inward, where one can see without looking, in the imagination. The caves were a kind of inward brain for the earth, the common body, and they put the animals there, so that Lascaux might dream forever of her animals, as man in the lust of their beauty and in need of their blood, venison, marrow, and hides, and in awe of their power and cunning, thought of them sleeping and waking.

Often the historical fiction is entirely fantasy; a story called “1830” is crafted of a lie Edgar Allan Poe told about traveling incognito in Europe and gaining audience with aristocrats. Another, “Belinda’s World Tour,” again appropriates Kafka’s voice, magnifying an anecdote of his meeting the distraught young daughter of his coworkers; she had that day lost her doll in the park. In the story Kafka relays to the girl news he has heard that Belinda isn’t lost; she had a sudden opportunity she couldn’t refuse. She met a dashing young doll her age, and they eloped. “Such things happen. Dolls, you know, are born in department stores, and have a more advanced knowledge than those of us who are brought to houses by storks. We have such a limited knowledge of these things.”

Lizaveta stared.

But the very next day there was a postcard for her in the mail. She had never had a postcard before. On its picture side was London Bridge, and on the other lots of writing, which her mother read to her, and her father, again, when he came home for dinner.

Then come thirteen postcard messages “in haste,” quickening depictions of place and peoples, from London and the Faeroe Islands and Copenhagen and Saint Petersburg and Tahiti and San Francisco. The upswept passion of the doll’s adventure with Rudolph (“Have I said that Rudolph is of the royal family?”) is also the tender protracted severance between loving friends, a lesson on the subjectivity of others—even the otherness of transitional objects—until the final card from Niagara Falls is signed, “I will remember you forever. Mrs. Rudolph von Hapsburg und Porzelan (your Belinda).”

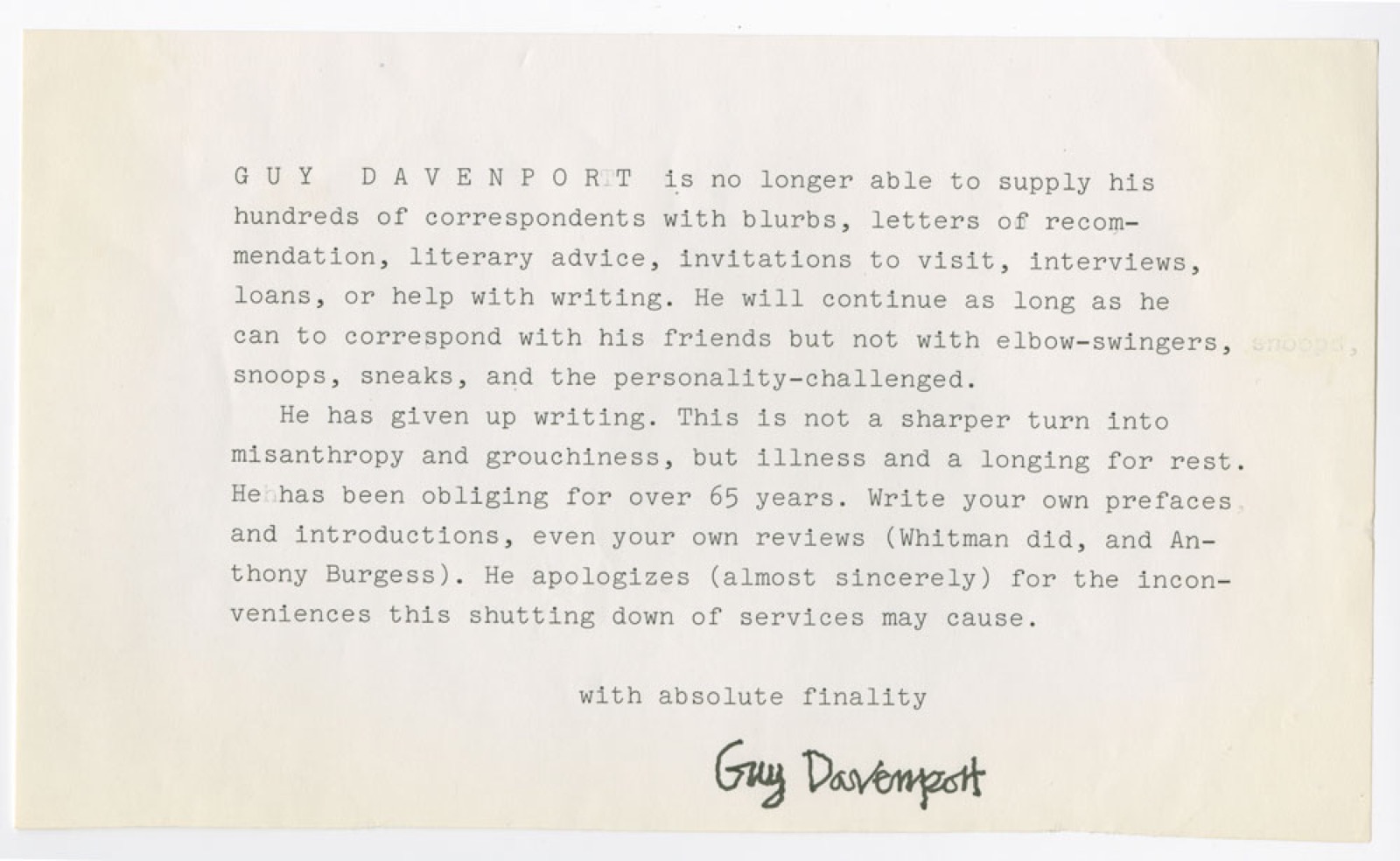

Guy Davenport’s form letter to writers. Harry Ransom Center, The University of Texas at Austin

Guy Davenport’s form letter to writers. Harry Ransom Center, The University of Texas at Austin

“Can’t I just be a plain modernist?” Davenport once asked an interviewer, who was sizing him for the terms postmodern and meta-modernist, given his penchant for appropriation and intertextual fiction, writing in or as other authors. “Aren’t I old enough?” he added. Davenport didn’t publish his first literary prose until he was forty-three, which happens to be my age, and he credits the films of Stan Brakhage for his aesthetic breakthrough: rather than tell stories, he could assemble them, so that “an architectonic arrangement of images has replaced narrative and documentation.” Davenport’s more recognizably modernist forms have what “Belinda’s World Tour” has: an isometric structure, an array of equivalences—paragraphs as verses—to which the through line of plot or argument is only incidental. This is true of his nonfiction book A Balthus Notebook, which exists entirely in four-line paragraphs of discrete perceptions about Balthus’s paintings, opening onto numerous assertions about the historical construction of childhood (“a durée discovered by the Enlightenment”): “The only clock I can find in Balthus is on the mantel of The Golden Days at the Hirshhorn, and its dial is out of the picture. Balthus’s children have no past (childhood resorbs a memory that cannot yet be consulted) and no future (as a concern). They are outside time.” It brings to mind another choice Davenport fiction, “The Wooden Dove of Archytas,” which alternates evenly between two stories of children inviting dubious adults to a ritual: a Cherokee girl in the postbellum South asks the black field hands, her Christian neighbors, for a matchbox in which to bury Dovey, a ringdove who had been her companion, and they attend the animist ceremony—while a young Greek boy asks his Pappas and Pappos to come to a demonstration at his gymnasium, in which the older boys and their Pythagorean teacher will give flight to a winged wooden bird, powered by compressed steam. The ascents of the doves are parallel in the braided story. And, the story itself is entwined, across Davenport’s oeuvre, with his collage story “The Concord Sonata,” which opens with Thoreau’s gnostic quest in Walden to recover a turtle dove, as well as with the story “Jonah,” a retelling (“His staff was of olive and his name was Dove”), about whose name, in another late story “The Ringdove Sign,” a theologian character reasons that Jonah, Hebrew for dove, suggests that ancient daimons, many of which are birds, were removed from the Bible or remain as vestiges, perhaps in contorted forms. This theologian is one of a few personae, typically an improbable Danish Calvinist libertine stoic who knows his Plato, who stroll the longer fictions, developing his philosophy or scholarship, as the qualities of his Arcadia likewise develop—namely, sudden awakenings to sex appeal in congenial youth—as though the former depends upon the latter. Congenial is a favorite word in Davenport, and somewhere he tells us its etymology suggests kinship with the genii, the local gods, of a place. For sure, no such Calvinism belonged to North and South Carolina, not in his 1930s, nor in my 1980s.

“Every force evolves a form” goes the Shaker dictum after which he titles an important essay. Is that how we came up with Guy Davenport? I want to close with a fuller taste of his “plain modernism” that might illustrate the saying and let the writing speak for itself, but first it seems right to present (and test) two other objections he was wont to give to misconceptions. He was not a Southern writer, he once insisted to Alfred Corn. He demonstratively stacked his books and pointed out how proportionately few pieces therein addressed the South directly, implying the interview ought to detour from that track. But, suffice it to repeat, he also was no Susan Sontag. On the face of it, he was both of those things to which the modifier “Southern” most swiftly attaches, an eccentric and a gentleman. There he is, photographed like his friend down the road, Thomas Merton, in Gene Meatyard’s grotesque Lucybelle Crater masks, in the same cardigan and on the same lane he could be seen wearing and walking, briefcase in one hand, collecting firewood for his nightly fire, on his way home from campus. Asked once to address “the confrontation of self in imaginative writing,” he begins his essay with an ahem of politesse: “Talking about oneself is a feast that starves the guest.” That’s something my grandmother, or his, might have counseled, and for background you might imagine her heavy flour drawer opening and the chock-ticka-chock of the sifter resuming once it’s said. But he finds the axiom in Menander, fourth century b.c.e. That essay, extraordinarily generous on the topic he accepts, is nonetheless titled tellingly. “Ernst Machs Max Ernst.” He makes a sentence of the names of two figures he admires and seals a tautology as prohibitive as Pope’s “the proper study of mankind is man.” In what follows, he upholds Max Ernst for finding a way to make the familiar strange and contrasts his surrealism favorably with the “dullness and triviality” of Dalí: “the raw and unexplained dream still has its power; the dream with legible symbols is a spent force.” (No fan of Freud, Guy Davenport.) Similarly, “it can be said,” he goes on to say of his own stories, “that I hope there is meaning inside, but do not necessarily know. I trust the image; my business is to get it on the page.” It’s a compatible declaration to the one in “Finding,” where “from a whole childhood of looking in fields” he learned that “the purpose of things ought perhaps to remain invisible, no more than half known. People who know exactly what they are doing seem to me to miss the vital part of any doing.” And elsewhere, of himself, actually, upon meeting Ezra Pound and not being thrown by the man’s paranoia, “Southerners take a certain amount of unhinged reality for granted.”

“Erotic” is the other word Davenport did not care to have applied to his literary work or his motivations. Desire and its damages, I suspect, were all too real. I’m sure it was in a Davenport story, “The Antiquities of Elis,” that I learned there was also a god Anteros, who unlike his brother Eros was “Love Returned, the principle by which boys in love with each other do not act like boys and girls, but sustain decency and chastity in their friendship.” Hm. Love returned: in all the sex and carnal horseplay in Davenport, whatever the century if any, there is never yearning or agony or thrall or withholding between the pleasured bodies, some of them quite new to the electric sensation of being apprehended sexually. And there is a great deal of care and loyalty and play, and an inspiring amount of permissive openness. The problem I confront, when it is unsettling, as when he resorts to Latin (italicizing literally) to refer to genitals, is prurience, a kind of dollplay in the sexing—one grows too aware of what or who is bringing the young bodies together serially and in new arrangements, smiles all around, indistinctly fetching. Davenport was a reader of Charles Fourier, whose early nineteenth-century utopian philosophy and planned communities I have only read about, but who is cited in early Marxist theory for his elaborate concepts of moneyless communities where the family unit is dissolved in favor of communal hordes, structured into phalanxes of about 1,600 persons each. A few Fourierest New Harmony communities were established, in New Jersey, in Ohio, during and after his lifetime; Horace Greeley, for one, was all in. Fourier’s larger idea was, according to Davenport, to discover human nature, uncultured, with no moral prohibitions; and the project was in a way to be defined by children, “a society of children organized into hives and roving bands. Adults were, so to speak, to be recruited from the ranks of this aristocracy.” It had the sort of radical reset Davenport admired in any thinking artist, Montaigne, Wittgenstein, Stein, Merton, following his or her genius. And, irresistible to a classicist and empiricist like Davenport, Fourier believed like Pythagoras in aligning the patterns in nature that order everything from musical harmonics to leaf arrangement on a stem. In his most ambitious, thirty-section collage fiction, “Au Tombeau de Charles Fourier,” Davenport weaves seven or eight intermittent narrative strands, including a colloquy between the gods of disruption and preset uniformity in Dogon mythology, Davenport’s own 1974 conversation with Samuel Beckett, the decomposition of Fourier’s resting body in his Montmartre grave, the organization of pleasure in one of the phalansteries of a what-if Earthen paradise, and the behavior—yes—of wasps. If artistic intuition, unconforming, may evolve a form, Guy Davenport’s assemblages result from his savoring, together, what is closest at hand and farthest in fantasy. Congeniality is the coin of the realm.

For spending the day with an elder and looking intelligently at everything shown and listening with full attention to everything told, ten centibona. And then there were the decorations differing from phalanx to phalanx given for the fun of distinctions.

These were in millicupidon points convertible through Common Measure into centibona, called mush in Horde argot, for freckles, bluest eyes, messiest hair, dirtiest feet, mentula longissima, silliest giggle, slyest wink, grubbiest fingernails, charm.

Goldenest smile, earliest pubic hair, nautch in the innominata, largest number of warts, longest period between the frumps, slickest kiss, keenest whistle, worst joke, roundest behind, highest pisser, brightest glow from a dandelion under the chin.

A wark in the gaster, a curr in the jaws, and she flies in a figure eight. She bounces in the air, trig of girth and smelling of gingerflower wax, of apples, of vespa. She thirls her wings, clapfling and brake flip, shimmering her neb. She dips.

He zips in for a squinny, mucin in his ringent jaws, buzzing. She hums. He rimples his golden crissum, sprag for a hump. He brushes her antennae with his forelegs, she his. They dance, a jig, insect of ictus, in linked orbits, more wiggle than step.

Zizz! She pounces, lifts him with all her legs, and flies up. He dangles, wings closed over feet. Over the rose she carries him, through the liliodendron, between the zinnias and sage, peonies, hollyhocks and comfrey, color milling in a quick of sugar.

Enjoy this story? Subscribe to the Oxford American.