Botalaote Hill

By Gothataone Moeng

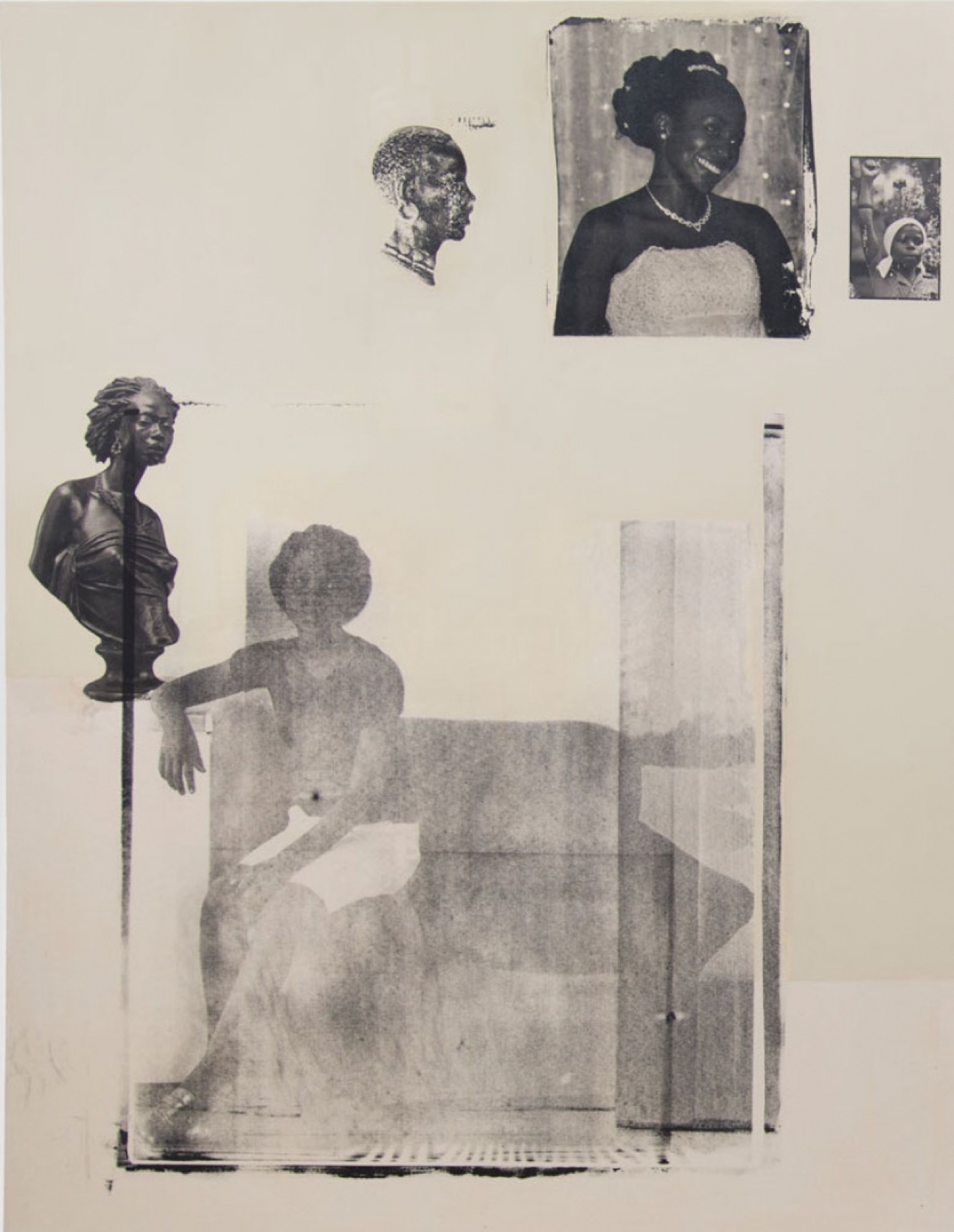

“Democratic Intuition, Comrades: Addendum” © Meleko Mokgosi. Courtesy of the artist and Jack Shainman Gallery

In the morning, woken by the two gunshots, I heard the rising flurry of ululations that followed and knew immediately that I would go to the wedding, no matter what my mother said or did. I understood that the two cows to be slaughtered for the feast had collapsed upon the swirling red dust, that an old man would be stalking toward them to plunge a knife into the quivering warmth of their necks, that soon the whole yard, only five compounds away, would be swarming with joyous people. My friends would be there and I wanted to be there, too.

In my cousin Tebogo’s room, which I shared, I lay in my bed, listening to my mother’s feet thumping up and down the passage, forcing the whole household awake. Doors slammed in her wake. In the kitchen, dishes clattered, hot cooking oil splattered, and the aroma of frying potatoes rose. In the bathroom, where my parents conversed, water streamed into the plastic tub my mother used for the patient’s bath, her voice weary and my father’s distorted by the toothpaste foaming his mouth. Water slapped at the sides of the tub as Mama lugged it into the patient’s room—formerly mine—on the other side of the wall I was tapping my foot against. As I did every morning, I imagined I could smell the Dettol disinfectant Mama eddied into the water with her fingers, I imagined the steam fogging up the mirror I had bought for myself and stuck up on the wall, I imagined the steam warping my books and my posters and my photos and my magazines.

I did not want to think about my mother’s hands bathing the patient—her sister, my aunt—so I thought about the wedding. I knew that the men would be draining the cows of their gushing blood, peeling off the skins to reveal the fatty meat underneath, slicing the bellies open and offering up enamel bowls to receive the tumble of glistening intestines. I knew that the men would be kicking away the intrepid dogs slinking toward the meat and at the same time would be playfully jostling with the women about which cuts would go to the men for the seswaa and which to the women for the beef stew. I knew that a congregation of aproned women would already be working at the fire at the back of the yard, boiling beetroots and potatoes, peeling and slicing and cubing cabbages and carrots, for the salads for the coming crowds. I knew that the women would soon break into their songs, celebratory and teasing—The cakes are delicious, but marriage is difficult, we are leaving, you stay and see for yourself—and that they would dance and ululate and whirl around the bride—come out come out, come and see, this child is as beautiful as a Coloured—as she walked on the carpet, which had been laid out so her white dress would not touch the red dust of the yard. I knew that almost all the people in our ward, Botalaote Ward, would be at the wedding, everybody except the very old, the new mothers, the newly grieving, and the sick.

It was three weeks since Tebogo and I had finished our Form Two exams and a month since the patient had been brought home from the hospital. After completing my exams in October, I dreamed of doing things, of going away while my mother and father were at work, of visiting my friends in their wards and wasting the luxury of the day with our talks about boys and such. But since the patient had arrived, it seemed my mother did not even want me to leave the house.

In my and Tebogo’s room, I stayed in bed listening to my father complain about how much time my mother was taking, about MmaBoikanyo, the day has begun, about MmaBoikanyo, what will people say, about MmaBoikanyo, people will think we are scared of work. Mama was a big woman, with a lot of energy and a miraculous capacity to complete half of her daily chores before the rest of the household awoke. Before the patient came into our house, when Mama woke Tebogo and me up at 5:30 A.M.—talking her old stories about a woman needing to be up before the sun—she would already have a pot of soft porridge and a kettle of Five Roses on the stove. On weekends, she left early for funerals and, often, by the time Tebogo and I awoke, she would be back, her shoes kicked off, sighing over her tea, poring over the funeral program, an addition to the pile she kept in her bedroom. Before, she was just like the other mothers. She shouted orders and called instructions for chores. But since the patient had been brought to stay with us, Mama was different. She still rose early, but sometimes she would put on a pot of water and forget to switch the stove on. Sometimes she forgot the name of the woman she had hired to take care of the patient during weekdays. Sometimes she called home from the furniture shop she worked for and forgot why she had called, or called home when really she wanted to call the district council office to talk to my father. On weekends, when she had to go for a funeral or a wedding, she came into our room, apologetic and full of bribery. I knew she would soon come.

Mama knocked and opened the door.

“Banyana,” she called softly. Tebogo started snoring, the sound see-sawing, see-sawing, and I wanted to laugh. I kept my face to the wall and my eyes closed.

“Girls,” Mama said again, her voice invading the room. “Are you awake?”

I felt my bed sinking under her weight as she sat down.

“Boikanyo,” she said, calling my name. I turned around. I opened my eyes. I yawned and stretched my body.

“Dumelang,” I greeted her. Mama looked all fancy in the dress made from the blue German-print fabric that the married women had chosen as their uniform for the wedding, but her hair was still covered by the brown stockings she wore to protect it overnight. The skin on her forehead was raised and pulled back, so I knew her cornrows were tight and still painful. She reached her hand out to touch my shoulder.

“I am up,” I said, before she could touch me, and sat up on the bed.

“I made you some fresh chips,” she said.

I folded my arms and leaned back against the headboard, shivering as its coldness startled the small of my back.

“I put a bit of brown vinegar on them,” she said. “Just the way you like. And some chilies.”

My mouth watered at the thought of the chips, cut in thick chunks, heaped in a bowl, vinegar-drizzled, speckled with red chili flakes.

“MmaBoikanyo,” Papa called from outside the door, “please, woman.”

My mother turned her head to the door. “Everybody knows we have a patient, RraagweBoikanyo.” She turned back and smiled at me.

“Ao Mama mma,” I said, “I also want to go to the wedding.”

“I will come back early,” she said. “Then you can go.”

She had said this to me before, on a day I wanted to get my hair braided. I considered bringing that up but, though Mama had changed, I was not yet sure of how much backtalk she would tolerate without an instinctive back-of-the-hand slap, without calling in the reinforcement of my father. I had never minded obeying my mother, doing everything she wanted—sweeping the yard, cleaning the house, making tea, watering the peach and mango trees, doing my own laundry, going to the store for fat cakes and paraffin and meat—but since the patient had come, all the buying of forgotten necessities went to Tebogo. It was her pocket now that jingled with change from trips to the shops. She returned popping gum, her pockets full of toffees, and, always, she would toss just one toffee and one piece of chewing gum my way.

“Okay,” I said. “But Tebogo can’t go either.”

“It is you your aunt needs,” Mama said. “Now, come on, get up, what kind of woman are you if the sun finds you in bed?”

I got up and watched Mama and Papa leave. Mama had switched the stockings on her hair for a headscarf that matched her dress. An apron hid the pleats in the skirt of her dress. Under her arm she carried the pale yellow enamel bowl that she used at every such function; she had her initials—D.B.—written on the bottom in brown paint. My father, in his dark green overalls and a wide-brimmed khaki hat, looked different than when he went to work. He looked like he was going to dig a ditch.

I went into the kitchen. I uncovered the bowl of chips on the table. I took one and bit into it. The potato was only half-cooked, so I spat it out.

Outside, the sky was a vast blue dome, steadfast and distant, enshrouding the whole ward, the whole village. Wisps of white clouds trailed on the sky’s surface. The air was already dry, so I knew it was going to be another hot day. From MmaTumo’s yard several compounds away, where the wedding was being held, the intermittent sounds of car horns and ululations taunted me. Standing on my tiptoes on our veranda, I could see the green top of the tent where the bridal party would sit to be ogled by everyone. I wanted to see the multicolored balloons that I knew would be strung all around the entrance.

I went to my old room, the patient’s room, and cracked open the door. It was November, yet she lay on her mattress on the floor—asleep?—under a sheet and a blanket. Above the blanket, her head poked out. What used to be a full head of hair was now just dust-brown and reddish wisps. She lay on her side, facing the wall. Sometimes we lay face-to-face, I realized, with only the wall coming between us. I shut the door and went into the bathroom.

When I walked back into our bedroom from the shower, Tebogo kicked the cover off her body. She stretched and yawned loudly, wide-opening her mouth. I applied lotion to my body in silence and put on my favorite yellow sundress with the spaghetti straps.

“What are you getting dressed up for?” Tebogo asked.

“Mama said you have to stay home,” I told her, “to help with the patient.”

“You are lying,” Tebogo said. “She didn’t.”

“Yes, she did.”

“I wasn’t sleeping, ngwanyana, I heard her.”

“You have to help me,” I said. “Papa said.”

“She is your aunt, not mine.”

Tebogo was the only daughter of my father’s only sister. When her mother found a job in Mahalapye, Tebogo stayed in Serowe with us because her mother lived in a one-room house in a yard full of other one-room houses. We were both fifteen and had only a two-week age difference. I was the older. When we were younger, our mothers would dress us in the same sets of clothes, differing only in color, and in primary school we told everyone that we were twins. We looked too different though—I was all dark, all skinny, all gangly. She was shades lighter than me, but not light-light, not yellow-light. She was on the girls’ soccer team and had huge muscles in her legs. Whenever she came from soccer practice she would eat a pile of phaletšhe—whether there was beef stew or morogo or not.

“Mama made me some chips,” I said. “You can’t eat them unless you help me.”

“In my own uncle’s house?” she said. “You won’t give me food in my uncle’s house?”

“Mama made them for me.”

We raced to the kitchen. I got there first and held the bowl of chips high above my head.

“Okay,” she said. “Fine. I will help.”

We put the chips back into the pot, which was full of oil, and switched the stove back on. Then we sat at the kitchen table eating the chips with slices of bread, washing them down with cups of tea. Tebogo speculated about what the bridal party was wearing and in the same breath said they were probably not as well dressed as the one she had seen at a wedding in Mahalapye. The previous year, her mother had taken her off Mama’s hands for two weeks during the second-term break. Since then, nothing in Serowe was ever as good as anything in Mahalapye. The town was only two hours away, but Tebogo acted as if she had been all the way to Gaborone, or even to Johannesburg. She explained everything on the television, and tried to convince me that she had learned new dances up there.

“Ao mma,” I said. “Still talking about that wedding?”

“I am telling you,” she said. “That bride was beautiful, and the bridesmaids, wena, heish, and the men. I am telling you. Even you, you would say so if you had been there.”

The wedding sounds followed us into the kitchen: Brenda Fassie songs and, just before noon, a cacophony of car horns and a swelling of ululations.

“Oh, they must be arriving from the church,” Tebogo said. We ran outside, she still in the shorts and t-shirt she wore to bed. Cars inched past our yard, balloons blooming all over their windscreens and their side mirrors. Tebogo ran out, through the gate, alongside the cars, without even bathing first or anything.

“You smell!” I yelled at her. My stomach clenched with the desire to be there; my chest ached with the frustration of not being there. I sat on the veranda, shouting greetings at all the people who walked past our yard.

I went in to check on the patient. She seemed asleep. My Boom Shaka and Arthur Mafokate posters were still on the wall. I removed a plastic bag with two rolls of toilet paper in it from the magazines I kept stacked by my wardrobe. I wrinkled my nose against the smells of the room: the Dettol disinfectant, the damp towels, the stale urine, the adult diapers. A half-finished bowl of soft porridge and milk sat on a side table far from her, jostling for space against the giant bottle of Dettol and a roll of cotton wool. Her breaths were loud and ragged, taking so much effort that the blankets rose and fell with each one. Sometimes the breaths ended in moans. Her cheeks were so sunken it looked like she was perpetually sucking at a mint hidden in her mouth. Sometimes when I went into the room, she tried to talk to me. I could not look at her then. Her speech, interrupted by coughing, trailed wisp-thin and low, required me to lean in, to look at her disgraced and hideous face. It made me angry, that she required this of me, as if she were still my aunt Lydia.

Before she was the patient, my aunt Lydia never looked like this, pitiful and vulnerable as though she were a newly hatched chicken. Before, she had her own car. A cheap Corolla that she took on drives from Orapa, where she lived, to Pilikwe to see her and Mama’s parents, and then, always, to Serowe to come see Mama. Whenever she came to visit, she would share my room and my bed. At night, I fell asleep to her stories about her and Mama’s life when they were younger, way before every household had a landline, about the boys who made bird sounds behind the house as a signal to the girls to come outside. Mama spent a lot of time in the room with us, for Lydia was good with hair. She would often plait Mama’s hair first, then mine and Tebogo’s. Lydia sat on my bed, and Mama sat on the floor between her legs. They fought over the mirror the way they must have done when they were younger. When she did my hair, she would turn me around so I could face her.

“Look at you,” she would say. “You are so beautiful, you are going to give these boys some trouble.”

“Lydia, what are you saying to my child?” Mama would say.

“But you know boys are trouble, right?” my aunt Lydia would concede. “You should take care of yourself.”

Mama and Lydia giggled at the latter’s stories of life in Orapa, a mining town, stories about her friends, all of whom she only called by the cars they drove—Audi, Jetta, Benz, Hyundai, Venture. When Aunt Lydia was at our home, Mama became somebody else—somebody softened into girlishness, who called her sister “girl,” whose lips and teeth darkened from sipping red wine, who gently teased Papa into coyness by greeting him when he came into the room with, “Hello, my husband, hello, my man, hello, sweetheart.” I kept still during those times, for I felt I was witnessing something I wasn’t supposed to.

Aunt Lydia made Tebogo and me dance for them. My face grew hot because of their laughter, in spite of their cheers, but I would force myself to finish because then my aunt would take us in her arms and say, “You two will go far! Gaborone! Johannesburg! New York!”

Outside, I stood on the veranda, but I still could not see anything. I went up to the gate, leaned my body against it. Two boys came up the road talking loudly. When they saw me, they lowered their voices and turned and walked up to me. I recognized one of them—the one with the sides of his hair completely shaved off. He was fat, with round cheeks that made him look twelve and like he was on the brink of laughter. His friend was taller, wearing blue jeans and a t-shirt with the sleeves cut off.

“Eita,” the boy I recognized said to me. I assumed the angry and bored look I reserved for boys. I continued looking in the direction of the wedding, as if they had not spoken to me.

“Aah, come on, baby,” the tall boy said. “Come on, talk to us.” He was just as tall as me. His face was pockmarked from pimple scars. His bright red Converse All Star shoes matched his hat, as if he had come straight from a kwaito music video.

“Baby?” I said.

“Okay, then, woman,” he said, while his fat friend giggled. “What’s your name, woman?”

“What’s your name?” I asked.

“Sixteen,” he said.

“What kind of name is that?”

“Tell her your real name,” his friend said and giggled again, then looked at me. “Sixteen is his soccer name.”

“Okay, fine,” he said. “My name is Perseverance.”

I considered using one of the names I kept in rotation for moments like these, simple common names that every other girl had—Neo, Mpho, Sethunya. Sometimes I used Tebogo, but I thought it was sweet that he told me the name that embarrassed him. I told him my real name.

“So, where can one see you, Boikanyo?” he asked.

I hated when boys talked like this to us girls, using a voice that was not really their own, a language they still felt uncomfortable in. But I liked the way he rubbed his hands together, as if he were nervous to be talking to me. I liked his plum-dark lips.

“What do you mean?” I asked. I was embarrassed by all the people walking past, seeing me talk to the boys.

“If I want to see you, where could I see you?”

“I don’t know,” I shrugged. “I am always home.”

He cocked his head to look past me at the house.

“I can come here and go knock on the door and ask for you?”

“No,” I scoffed. Papa had already cautioned Tebogo and me against, as he called it, laughing with boys in corners. A heavily pregnant lady walked past, slow and lumbering, and I could feel my face growing hot at her lack of shame, showing that she had done it.

In the distance, I saw Tebogo walking back home. When she reached us, she opened the gate and closed it against the boys and stood beside me. She wrinkled her nose and said, “What’s going on here?”

Sixteen’s friend said, “Eita.”

Tebogo looked at him and said, “Aren’t you MmaTsiako’s grandson? How is your grandmother?”

“Ao, sisi,” the boy said and giggled. “Come on, we are just talking.”

“You are needed in the house,” Tebogo said to me. “Come.” She grabbed my arm and pulled me behind her. I knew that she thought she was rescuing me from the boys, but I did not want to be rescued.

“Boikanyo,” Sixteen called. “What do you say, BK?”

When we got into the house, we collapsed onto the sofa, giggling, careful not to wrinkle the cloths Mama used to cover the seats.

“I am going to tell my uncle,” Tebogo said, “that I woke up and found you kissing a boy right here inside his house.” I threw a cushion at her.

“‘So, what do you say, BK?’” she said, imitating Sixteen.

“Voetsek,” I said. “Tell me about the wedding.”

“That bride, she is so beautiful, shem, but her hair.”

“What’s wrong with her hair?”

“It’s just a push back!” she said. “Can you believe it? Shame, so plain. I can’t believe they think that hair is suitable.”

I knew where the conversation was going, so I tried to avoid it.

“What about the bridesmaids—what are they wearing?”

“Oh, they are wearing these nice bright-orange two pieces, shem, the girls are all too dark for that color.

“Anyway,” she said, getting up. “I am going to shower so I can go back.”

“You just said the bride is plain and the bridesmaids’ dresses . . . ”

“It’s still fun. I saw Peo and Mpho.” My friends from school. I was sure that Sixteen and his friend had also been going to the wedding.

“Okay,” I said. “I am going too.”

“What about . . . ” she nodded in the direction of the patient’s room.

“But me, I also have to eat my youth,” I said, and she bent over to laugh. We had started this thing where we talked about our age as if it were a tactile thing outside us, a thing not to be enjoyed at leisure, a thing to be gobbled up.

“Okay,” she said. “But I don’t want to hear my name if you get into trouble.”

While she finished dressing up, I went into the patient’s room. She had turned over. I helped her sit up in bed, propping pillows between her back and the wall. I avoided her eyes. I held the bowl of milk and porridge up to her lips, and supported the back of her head. I helped her lie back down.

After, I washed my face, and Tebogo and I went into Mama’s bedroom, whispering as if she could sneak in and catch us red-handed. We darkened our eyebrows with eyebrow pencils. We drew a mole above our lips, the only identical feature on both our faces.

MmaTumo’s yard, where the wedding was held, was like the other yards in our ward. Most had chain-link fences, sometimes with a hedge or green-milking tree planted along the fence. Most had a main house in the center of the yard, flanked by smaller houses, sometimes a mud hut, sometimes a one-room brickhouse or a two-and-a-half.

MmaTumo’s had a mud hut that she usually used as an outside kitchen. It had been improved before the wedding, a layer of mud reapplied and decorative patterns drawn on the wall in different colored clay. A new addition to the hut was the lapa where the bride and groom would be given instructions for their new lives. The tent had been set up opposite the main house such that, from the gate, it obscured the mud hut. When you entered from the main gate, the tent was the matter of pride one saw first.

Tebogo and I went straight to the tent. The balloons on the entrance were half-deflated. Inside, a group of kids fought over the ones that had floated to the ground. The fancy chairs behind the top-table were unoccupied; the bridal party had gone to change into their second outfits. Half-empty bottles of wine littered the top-table and all the tables inside the tent. Ceramic plates retained leftover samp and cabbage, and meat-stripped bones. The tent itself was half empty. Most people had gone to watch a choir performing outside.

“Let me go outside,” Tebogo said, “and see if I can see Auntie. If I can’t, I will come get you.”

I went to sit at a table at the very back of the tent. I looked around for Mama, for Papa, for Sixteen, for any of my friends. I hoped dessert would still be coming.

I wondered if the patient could hear the music from the wedding. I imagined her dying, all by herself in the house, her body discovered hours later. I wondered how Mama would take it, whether she would go around the house with her eyes swollen and red, whether she would ever call me Boi-nyana like she did when she was happy. I thought about being back in my room, waking up to R. Kelly smiling at me from my wall.

The first two weeks the patient was home from the hospital, Mama took time off from work. During the day, she carried steaming bowls of bean soup and soft porridge back and forth between the kitchen and the patient’s room. Women from the neighborhood trooped in and sat in the sitting room, talking in loud voices over tea Tebogo and I made: “Mma, wena, did you hear about MmaTsiako’s daughter?”

“Owai, as for my uncle, MmaBoikanyo, there is no person there either. We are just counting the days.”

“I can’t believe that I never heard that RraEtsile’s little niece is gone.”

“Oh, yes, yes, she is resting. Poor girl, she was in so much pain.”

Inevitably Mama would have to bring out the pile of funeral programs she kept in a nightstand drawer and fish out the one that a visitor could not place. The women would look through all the other programs, sighing and clucking as their tea cooled on the coffee table. Then they would go into the patient’s room, their voices low and reverent, coaxing her to tell them how she was feeling. I heard her—coughing, coughing. Her voice, hoarse and exhausted, murmured alongside and weaved with Mama’s sometimes. Then her low laughter, different and new, was interrupted by coughs, and my mother’s gentle cajoling. When the women left the room, their voices returned to their normal loudness, and they called out to Tebogo and me to offer them a drop of water to prepare for the heat they would be walking out into.

Tebogo did not return to get me, so I walked around, keeping a wary eye out for Mama, Papa, or any of their friends. I saw Peo and Neo among the group watching the choir and walked up to them. They swatted at me playfully.

“Shee, kante, where have you been?” Peo asked.

“Just home,” I said. “Protecting my complexion.”

“Owai, what complexion,” they laughed. “You are still as black as coal.”

“You are still as black as the tar on the road to Gaborone.”

“You are still as black as those pots full of seswaa right now.”

“You will still be black at senior school next year.”

Their jokes stung, but were better than how they would mock me if they knew I had been wiping crusts from my aunt’s eyes. I saw my father in the crowd of people dancing. He saw me mid-song, smiled, and raised his hand to wave at me. Then I could tell he remembered I was supposed to be home, and he frowned, looking around.

“Sharp, I will see you,” I said to Peo and Neo and walked away into the tent again. As I sat down, a surge of ululations started up. People who had been sitting under the shade of trees got up and walked forward, so I knew that the bridal party had changed and that they would be dancing back to the tent. I stood against the tent, right by the entrance, on the left flap where I knew I would be able to see them when they came in. A photographer ran in, climbing on tables and chairs. The bride, her white veil gone, kept her face down. Her hair was in a push back. She was like a magnet; everybody hurtled toward her and her bridal party, but did not get too close, held off by her poise, her small and coy movements. She and her groom walked up to the top-table and sat down, flanked by their bridesmaids and groomsmen. The women had changed into blue German-print dresses with white embroidery around the sleeves. The men’s shirts matched the women’s dresses, but their embroidery was on the collars. Some of them, from the top-table, smiled and waved at faces they recognized. We all stared at the spectacle of their beauty, and filled ourselves with the pleasure we got from it.

Just then Mama came into the tent. I wondered if Papa had told her about seeing me. I tried to move away, to flatten myself into the fabric of the tent, afraid to breathe. But she did not see me. She concentrated on her movements. She kept her arms pressed against her breasts in the way that all the older women did before dancing, then she moved her shoulders up and down, she moved her upper body side to side. She bent first her right knee, then straightened and bent her left. She moved the excess of her body, slowly, proudly, seemingly uncaring that her headscarf had slipped off her head to reveal her cornrows. She danced, her eyes closed, a small, private smile on her face that I felt uncomfortable witnessing. Somebody chanted, “Dudu! Dudu! Dudu!” and only after some moments did I realize that it was my mother’s name that the voice was calling. Another shouted, “Does this child not have parents?” and a swelling of ululations answered him. I wasn’t sure if the person meant the bride or my mother.

Tebogo had found a bowl of trifle for me. Sixteen and his giggling friend had discovered my spot in the tent and now sat across from me at a table. The scent of ginger beer and wine filled the tent.

“Your beauty,” Sixteen said, “it fills me up.”

I looked around for any adults I knew. It was getting dark, and most people had gone to witness the bride’s final instructions for marriage. I decided to leave. Both Sixteen and his friend got up when I did, but only he followed me out of the tent. Sixteen walked behind me until we were away from the wedding, then he ran up, grabbed my hand, and forced me to stop.

“What are you doing?” I asked him.

“At least give me your phone number,” he said.

“Okay,” I said. “You can only call during the day, when my parents are at work.”

“Sure, sure,” he said.

He held his arms open and I moved into them, into his hug that smelled of sweat and grease from all the meat he had eaten.

“Sure, baby,” he said. “I will call you.” He walked me to the gate. All the way, I was nervous that my parents would emerge from the darkness behind me.

Sunday morning, I woke up thinking of Sixteen. Then I wondered when my mother would discover that I had been at the wedding. I had gone in to see the patient as soon as I came back. She had shrugged the blankets off herself, and I had sat her up so she could slurp the porridge and drink the water I gave her. I had wet a washing rag in warm water and wiped her face, and laid her down so she could sleep. Mama had not even come to check in on me when she returned. Still, I felt compelled to make amends, and went into the kitchen to start on the soft porridge.

The fridge was crowded with bowls and plates with various cuts of meat that my parents had received at the wedding. A piece of liver in a bowl, some seswaa for my mother and mokoto for my father. Mama would be mad if I ate any of it without permission, but I reached into one of the bowls anyway, for a taste.

As I was reaching into the bowl with seswaa, I heard a man’s voice say very loudly, “May the Lord’s Peace be with you!” I slammed the fridge shut and looked around.

“Peace be with you,” the voice said again, coming from outside.

A man in a white robe stood in the yard. Beyond him, outside the gate, a group of people from my mother’s church disembarked from a van. They came into the yard loud and boisterous, laughing among themselves.

“Mama!” I shouted.

The older women wore navy blue skirts, long-sleeved white shirts, and blue capes over the shirts. The younger women and men wore white robes, with navy blue sashes with the words FULL GOSPEL OF CHRIST thrown diagonally across their chests. All the women wore white starched hats perched atop their heads, because their push backs and braids and cornrows would not allow the hats to be pulled completely down.

“Your people are here, Mama!” I shouted again.

The congregation stopped and rearranged themselves into a choir outside the house, the women in front, the men at the back. The men lowered their heads to produce the bass to support the women’s voices. They clapped their hands and swayed in unison, and in a two-by-two procession walked into the house, their robes swishing back and forth.

Mama came out of the patient’s room tying her headscarf and draping a shawl across her shoulders. She met them in the passage and stood in front of the room, matching her clapping hands to theirs and taking their song up. Papa, Tebogo, and I joined the procession at the end and into the patient’s room, clapping and singing as well:

We are visitors in this world

We have a home up in heaven

This earth is not for us, friends

This world is not for us

We have a home up in heaven.

The congregation arranged themselves around the mattress. Mama pulled the patient up so she sat against the pillows. She kept her face, thin and unrecognizable, down. My face grew hot, in shame. The people all kneeled down where they were and started praying. I knelt, my feet touching the cold of the door frame, sweat collecting in my armpits. I opened my eyes and looked at the patient. Her eyes were open, too, wide and lively against the tautness of her face. They were the same eyes of my aunt Lydia who had once pulled up her shirt to show me the large birthmark on her stomach—darker than her skin, shapeless like a stain. She looked at me, and I looked at her, and as the people around us prayed for her recovery, she smiled at me.

Sixteen called the house from a public phone the following Monday. We arranged to meet at the foot of the Botalaote hill, behind my old primary school. The hill separated the ward from the school and the cemetery. Even as primary school girls, my friends and I believed the hill sheltered us from the omniscience of our parents’ eyes. On the school side, we could frolic as much and as roughly as we wanted and then, climbing back up and down to our homes, we assumed the obedient faces our parents needed.

Sixteen waited for me behind the school, looking through its fence at a group of boys playing soccer on the dusty pitch. I walked down slowly toward him, studying his body from behind—his legs, his arms, the contours of his chiskopped head, his neck melding into his back. I walked closer, looking at the way his butt protruded slightly in his tracksuit pants. I thought about his body beneath his clothes—his shoulders and chest, his thighs and knees, the only parts I could bear to think about. He turned around and smiled at me, and I stopped, a few feet away from him.

“Eita,” he said.

“Eita,” I said. I did not know where to look.

“Who is winning?” I asked, pointing to the shouting kids in the schoolyard.

“I don’t know,” he said, and I saw that he, too, was nervous.

“Come on,” he said as he reached out his arm. We climbed up, veering off the path beaten into the hill. He stopped under a tree whose roots had split a rock open. He pointed to the right of the tree.

“What’s this?” I asked.

“I found this place,” he said. “I like it.”

A rock jutted forward that one could climb upon and look beyond the school at the cemetery, beyond that to the tall Water Affairs building in the distance, to the small combis carrying people to the mall, or perhaps far beyond that. Under the jutting rock was a kind of cave, cool and dark, dank with the leaves littering its floor. We crawled in and the faint shouts of the soccer-playing kids sounded a world away.

“So,” he said. “I have been thinking about you a lot.”

“Really?” I asked.

“Yes,” he said. “What about you?”

“What about me?”

“I mean, have you been thinking about me?”

“Maybe.”

He laughed.

“What have you been thinking about me?” I asked.

“You know, just that I, heish, I am feeling you.”

The heat from my pleasure suffused my neck and my face. My heart beat loudly in my ears as he crawled over to sit in front of me.

“I mean, I love you,” he said in English. I lowered my face.

“What about you?” he asked.

“Me too. I love you,” I responded in Setswana, taking refuge in the lack of distinction between the words “like” and “love.”

“Okay, come here.” He sat me on his lap. He kissed my lips and I kissed him back, teasing his lips open with my tongue. I touched the back of his head. I slipped my hands down the back of his t-shirt. His back was sticky with sweat. That pleased me, as did his heart beating against my chest. We stopped kissing and just looked each other in the face, smiling like fools.

“So, I am your boyfriend?” he asked.

I nodded.

“No other boys, right?” he said. “I am privatizing.”

Tebogo said I was stupid for going out with Sixteen. A boy just a year older than me, a student, what good would he be to me, she asked, other than lending me pencils and pens.

“You don’t even have a boyfriend,” I said. We were in our room. She was lying on her bed, stretching her legs then bending them so her knees touched her chin.

“I want a man with a car,” she said. “He can drive me to school, drive me to the mall, give me money.”

“An old man,” I said. “Old leather.” There was a heap of dirty clothes on the floor beside her bed. Her soccer boots, caked with mud, sat upended by the door.

“He can take me to hotels,” she said. “So I can really, really eat my youth. Take me to a Miscellaneous game. Up the Reds! Up the Reds!” She whistled.

“I don’t care,” I said. “I don’t want your games.”

I knew that this—love and boys and relationships—was my own private experience, something I had over her, something for which she needed my knowledge.

“So, what have you two done anyway?” she asked.

“I shouldn’t tell you,” I said. “Things grown-ups do.”

“Please,” she said. “You are a child.”

“Oh, I am a child?” I said. “A child who was kissing her man yesterday.”

I flopped my body back onto the bed and sighed luxuriously to show her that this was a feeling that she could not understand, something much more than could ever be put into words.

“I miss him,” I said. “I miss my man.” A pillow thudded into my face from Tebogo’s direction.

Over the next weeks, I snuck away from home. Again and again. I left after lunch and ran back just before my parents drove in from work. Sixteen and I, we returned to our little enclave, a way for us to be out of sight. Sometimes we climbed up and dangled our legs down the overhanging rock. Looking out at the cemetery, I would think, sometimes with envy, sometimes with pity, about how the lives of the dead would never again change. In the quiet of the cave, we entered a new world where Sixteen would soften his voice, call me “baby,” swallowing mouthfuls of saliva, kissing my face and my neck, unbuttoning my shorts, pushing his always cold hands under my t-shirt to cup my breasts. He would take off his t-shirt and lay it on the ground for me to lie upon, and still the rocks would protrude through the shirt and poke into my back and my shoulder blades. I would adopt a baby voice, whiny and childish, and say, “No, no, I am not ready.” In some ways, I said “no” because I was afraid of what would come from him touching me like that, and in other ways because I thought it was what I was supposed to do—to play coy, withhold myself from him.

On the afternoon that we made love for the first time, I returned home, leaves mashed into the back of my head, so ground into my cornrows that I was still removing flecks of them on the Sunday I undid my hair to plait it again. I was convinced that the oily smell of condoms had seeped into my skin. I thought my mother would know as soon as she came close to me, so I stayed in bed all evening with a phantom headache. But even when I had arrived home, I found Tebogo sitting up on her bed reading and she did not say anything. She looked up at me when I walked in the door and went right back to The Collector of Treasures. I knew now that one could feel different and new and still appear ordinary to the world.

There were some close calls, days when I miscalculated the time and arrived just after Mama or Papa got home. Then I would go to our neighbor and pretend that my mother had sent me to borrow salt or a cup of sugar, and bring the sugar into the kitchen. I hardly ever went in to see the patient anymore.

One day, I opened the door and there my mother was, watching a soapie.

“Dumelang,” I said.

“Boikanyo.” She did not return my greeting. “Where have you been?”

“I wanted to borrow a book from Peo.”

“Where is it?” she asked.

“Mma?”

“Where is the book you went to borrow?”

“She wasn’t there,” I said.

I saw her getting ready to yell at me, but at that moment the patient began a coughing spell. Mama tried to wait it out, but eventually she got up to attend to her sister.

In our room, Tebogo was sprawled on her bed; clearly, she had been listening. I thought she expected me to laugh about getting caught. I knew she herself had been sneaking out some days to go swimming at the Serowe Hotel pool. I knew she enjoyed the thrill of having this other life the adults knew nothing about. But I couldn’t laugh about it, even though it seemed I had escaped my mother’s anger. I sat on my bed. I bent down to untie the laces of my takkies and pushed them off.

“She asks for you sometimes,” Tebogo said. “Lydia. When you are not here. Sometimes she asks to see you.”

“I am very busy,” I said.

“Hee, busy girl,” she said. “Busy doing what?”

“Just leave me alone,” I said. “Pretend I am not in your room.”

“My room? This is your mother’s house,” she said. Then, when I did not respond, “You are so stupid.”

“I don’t want to see her, okay?” I said. “I don’t.”

“Okay, okay,” Tebogo said.

The first week of December I ran home as usual before 4:30 P.M. My father’s van was parked outside the gate. A group of women sat out in the veranda, all wearing headscarves. Old men sat under the mulberry tree in the yard, their hats perched on their knees. Their gray heads looked young and naked without their hats. I knew immediately. I went to find my mother.

In the sitting room, Tebogo was on the couch beside my father. My mother sat on the floor where the coffee table should have been, her legs outstretched, her shoulders heaving silently. Her head was bowed, her fingers splayed over her face, as if it held something private and unknowable. I went to her and laid my head in her lap and cried loud, hot tears. After a while I became aware of her fingers plucking leaves from my hair. Around us, I could hear women removing the sitting room curtains, could feel the evening light entering the room. I knew they would be applying ash to the windows, an announcement to the world that we were a household in mourning.

Many years later, I lived in Gaborone, only four hours away from Serowe. I was childless and unmarried, shared my house and my life with a man, a photojournalist, a few years younger than me. I had traveled to Johannesburg, Berlin, New York, Kasane, Nairobi, Lagos, Bamako, Bahia, and many other places, sometimes for my work as a lawyer, sometimes for my own pleasure and curiosity. In Gaborone, my partner and I didn’t go out much, wary of the younger people who had taken over all the best night-out spots, even the Sunday jazz bars. Instead, we threw small parties at our house. I cooked the simple food of my childhood—marakana that we ate soaked in milk, or with goat stew, phane fried in just onions and tomatoes that we ate with bogobe jwa ting. I bought flowers and lit the fragrant candles that we kept in case of load-shedding: the house smelled of French vanilla and lavender and cinnamon spice. Our friends, lawyers and journalists, writers and professors, suffered the drive to Gaborone North. They brought wines and whiskeys bought during weekend trips to South Africa, for in Gaborone the cost of alcohol had become prohibitive. They exclaimed over the additions to our bookshelves and the fine art—photographs, paintings, sculptures—we were collecting. They filled the house with laughter. We drank and ate, and sat around talking, trying to make meaning of the art, the politics, the scandals making the news.

Often, the conversation would turn to that span of terrible years, before 2002, when everybody was dying, five funerals every weekend, all families affected. We still could not, with all the travels and the education and the knowledge and the expertise accumulated among us, we still could not make sense of those years. So many dead.

I never talked about my aunt. I told myself that her memory was mine to savor. Instead, I would often tell people about a boy I knew, who died in our last year of primary school. A group of us students went to the funeral in our school uniforms and right after, when the other mourners went back over the hill, we crossed the dirt road to start our school day. Whatever group of friends I told, what always fascinated people was not the boy’s dying, but this image, this juxtaposition of school and cemetery, side by side, and a hill cutting them off from the ward. It was as if they thought that, away from our parents, we kids fraternized with the dead. There would often be one person who thought that I was embellishing, that I was making up these details for the benefit of a story, to create some sort of meaning. That skeptic seemed to assume that the hill—which I now knew to be just a hillock—the school, the cemetery were symbolic of something that I had overcome, something I had escaped. But the Botalaote cemetery was separated from Motalaote Lekhutile Primary School only by a narrow dirt road and behind them the hillock cut them off from Botalaote Ward. Those were the facts.

Some days our teachers sent us into the cemetery with black rubbish bags to pick up litter. We went in, wearing our white shirts and cyan skirts, our white socks and polished black shoes. The smart among us took off their socks, rolled them into balls that bulged from their side pockets. Our shoes sunk into the red sand. Often we would have to stop and empty our shoes of the sand, but the grains would trouble us between our toes for the rest of the day. We picked up plastic bags and newspapers, Coke cans and condom wrappers, everything, to make the cemetery a place the departed could sleep in some beauty. Some of the graves were elaborate, with black marble headstones and engravings of the Madonna and child; a few were so old that there were just mounds of red dirt and a board with a name and a date of death. Most had a black cage-like enclosure with green netting hugging the tops of the mounds. Sometimes we would find plates and spoons on the graves, remains of food. Sometimes belts and ties, smoking pipes and other comforts, offerings to the deceased by those left behind, lest they forsake us.

Enjoy this story? Subscribe to the Oxford American.