Two greyhounds at night, 2019, oil on panel by Clare Menck © The artist. Courtesy 99 Loop Gallery

The Tangled Past and Unsettled Future of Greyhound Racing in West Virginia

In the home of America’s last active tracks, tradition and uncertainty run neck and neck

By Michelle Orange

This story appears in the Summer 2025 print edition with the title “Comely in Going.” Order the Y’all Street Issue here.

They look ancient because they are.

Eight in all, each one led by a teenaged handler in a royal purple t-shirt, the dogs cut a silhouette at odds with their surroundings. Moving from the paddock to the gated starting blocks, they squat and sniff and occasionally bark, appearing most themselves, or most familiar, when flattened in profile: the elegant, tapered snout, stretched-out torso, and tiny waist; the massive haunches and sickle-shaped curve of the belly. The same stark, primeval outlines can be found in Roman mosaics and temple drawings dating back to 6000 BC. The Greeks, the Celts, the Egyptians—they all loved the greyhound, or its close relations. Bred and cherished for its perceived nobility as much as its hunting prowess, no dog has been depicted as frequently, across as many millennia, or by a broader range of humans.

Signs of that linkage are scarce on an August afternoon in Wheeling, West Virginia, home to one of this country’s two remaining active greyhound racetracks. Yet despite the shambling, urine-soaked starting-block procession and barren, unsplendid backdrop, there persists a sense of something wondrous happening, of watching eight walking hieroglyphs pass by.

Earlier, inside the viewing bay—an eerily quiet, glass-enclosed grandstand where roughly two dozen people sat hunched, in clusters and alone, marking their betting sheets and sampling concessions—I stood with Kim Florence, the president and general manager of Wheeling Island Hotel, Casino & Racetrack, and Glen White, a representative of Delaware North, the resort’s Buffalo-based parent company. There, we passed the last ten minutes of our hour together pointedly not talking about the thing we were there to talk about. Behind us, a handful of old men sat facing a wall of television screens simulcasting horse races from around the country. Below us, a tomato-red dirt Zamboni groomed the 548-yard track during the eleven-minute break before the next of the afternoon’s eighteen greyhound races, each of which lasts about thirty seconds.

Time was, even ten or fifteen years ago, Wheeling Island ran thirty races a day. By state mandate, they must hold live races on no fewer than two hundred days each year. Since 2019, the year after Florida voters approved an amendment to ban greyhound racing at the eleven remaining tracks in that state, the already diminished number of racing patrons at Wheeling Island has declined by more than half. These numbers are not the stuff of happy executives, or budget meetings. Florence and White had agreed to meet with me but asked that the details of our conversation be off the record. Our tour of the facility included a stop inside the track kennel, where 144 dogs made a proportional racket from within their stacked wire enclosures, and the adjoining adoption kennel, where eighteen former racers snoozed in individual stalls behind a purple velvet curtain. Meant to showcase the track’s orderly and humane operation, the tour had also circled, in purely corporate terms, the question at hand: If these dogs are no longer driving company revenue, why are they still running?

The answer requires an unfolding of the origami compact by which certain pursuits gain and lose legitimacy—acquiring social and legal licenses and then, less often, especially if they are profitable, having one or both licenses taken away. The history of wagering in the U.S. is one such compact: Once the purview of gangsters and their prey, gambling in some form is now legal, and indeed a source of government revenue, in all but two states. The history of greyhound racing is another: By 1930, ten years after a man named Owen Patrick Smith opened the first commercially recognized greyhound track in the country, in Emeryville, California, there were sixty-seven such tracks in operation—all of them illegal. Five years after that, Depression-era economics had changed the political calculus: Florida, Oregon, and Massachusetts had all legalized dog racing; twenty more states were to follow, despite moral and personal objections voiced by various legislators, church groups, and animal welfare organizations along the way. Though dog racing lacked the glamour and prestige of horse racing and never became as popular, greyhounds were easier to breed and less expensive to keep. They were also an exotic concern: The first greyhound was registered in the U.S. in 1894, and relatively few Americans kept them for hunting or as pets. Trained using a version of the mechanical lure pioneered by Smith, the dogs could be conditioned to run without apparent regard for life or limb, easily reaching racehorse speeds—up to forty-five miles an hour.

By mid-century, greyhound racing had national and state infrastructures in the form of kennel, owner, and racing associations; breeding and trade groups; and a latticework of connections to organized crime. The industry remained loosely regulated as it gained in popularity through the 1950s, a decade in which celebrities like Paul Newman, John Wayne, and Frank Sinatra were spotted at dog tracks across the country. Track and kennel owners fought habitually over payouts, and by the 1970s media exposés began to detail animal mistreatment and overbreeding; the use of live lures, like rabbits and possums, in greyhound training, or “coursing”; and the destruction of unwanted or underperforming dogs. What was then known as Wheeling Downs, a horse track that opened in 1937, was converted to dog racing in 1976. The decision owed in part to competition from two nearby horse tracks and to the state’s passage of a dog racing bill in 1975, after the Downs’ then president, Joe Cresci, told West Virginia legislators that, in order to stay open, a pivot to greyhound racing was the track’s “only hope.”

Owned and run in its 1950s heyday by a 350-pound racketeer named Big Bill Lias—the kind of local mobster, both feared and beloved, who handed out turkeys on Thanksgiving but whose wife’s gruesome murder remained unsolved—Wheeling Downs was an economic hub, drawing tourists and driving employment. Lias was acquitted on federal tax evasion charges in 1949, but a similar case three years later led to the track’s seizure. After trying and failing to run it themselves, the feds hired Lias back and, in agreeing to his salary of thirty-five thousand dollars, made him the second-highest-paid federal employee in the country—next to the president.

Lias’s name was among those read into the Congressional Record in 1970, three months before his death, when an Arizona congressman named Sam Steiger charged Emprise, a family-run, Buffalo-based sports concession and investment conglomerate, with corporate calumny and dealings with various mobsters, including Lias. Two years later, Arizona Republic reporter Don Bolles gave congressional testimony linking the company to organized crime; that same year, Emprise faced felony fines for racketeering and conspiring to hide the true ownership of a Nevada casino. In 1976, before dying of injuries he sustained in a car bombing, Bolles claimed that Emprise, the mafia, and a man named John were responsible for his assassination. A greyhound breeder named John Harvey Adamson was convicted of murdering Bolles in 1977. Though never directly implicated in the case, in the wake of all this, in 1980, Emprise changed its name to Delaware North.

“Here comes Spunky!”

Each race begins this way: a female voice announces the activation of a white fluffball affixed to the end of a two-foot pole. Electric-powered, the lure moves along a copper rail on the track’s inside edge: just the roller-coasting sound of it makes the kenneled dogs go nuts. “Spunky is on the move,” the announcer says next, always with the same intonation, relaxed and droll. The lure rounds the curve with alarming speed, about to whip past the metal starting boxes where eight muzzled dogs are hidden, some of them barking, desperate, it seems, to spring forth.

They have names like Hashtag Uppity, Flamin Paws, Mizzen the Point, and Corona Virus. None that I see are gray, or what the official greyhound color chart calls blue. Black-and-white, along with various shades and brindles of red, fawn, and dark brown are most common. In the day’s printed program, certain kennel, owner, and trainer names repeat. Due to dwindling returns, three kennels associated with the track have closed in the last two years; ten remain.

Without the Greyhound Fund, all sides agree, the dog racing business would have collapsed several decades ago.

When Kim Florence was first hired, in 2003, Delaware North, which purchased Wheeling Downs in 1988, needed her help marketing the $68 million expansion and rebrand of what was about to be unveiled as Wheeling Island Racetrack & Gaming Center. In 1990, a failing West Virginia horse track installed video lottery terminals on the down-low, becoming the first “racino” in the country. Four years later, the state passed the Racetrack Video Lottery Act, making the combination legit. Before its passage, however, the dog- and horse-racing industries moved to ensure their livelihood wouldn’t be quadruple-cherried out of existence. The Greyhound Breeding Development Fund, established in 1993, requires that a percentage of West Virginia’s video lottery revenue be used to both supplement dog race purses—the prize money—and provide direct support to the state’s greyhound breeders and kennel owners. In recent years, that number has come to between $15 and $17 million annually; at Wheeling, casino revenue accounts for over ninety percent of the racing purse. Without the Greyhound Fund, all sides agree, the dog racing business would have collapsed several decades ago.

The entrance to Wheeling Island features a towering fake-rock formation, down which actual water cascades. Up an escalator is a gaming floor with a roughly discernable tropical theme: the odd plastic vine and palm tree with thick pineapple bark; walls and carpet patterned in shades of lime, teal, and mango. Over 1,400 slot machines, most unmanned on a summer Wednesday afternoon, generate the usual zero-gravity din. Delaware North added slots and off-track betting to Wheeling Island as soon as it was legal to do so. In 2018, the company bought Mardi Gras Casino & Resort in Cross Lanes, West Virginia, just west of Charleston, the state capital. Another greyhound track-turned-racino, Mardi Gras—like Wheeling—expanded its purview to include table games such as poker and roulette following the 2007 passage of the West Virginia Lottery Racetrack Table Games Act. Article 22C expanded the protections granted to the racing industry, mandating that any West Virginia property seeking a license to operate table games must also operate a racetrack, and added a minimum number of live racing days for any table games license to remain in order. Licensure to add table games also depended on a local option election: voters in the relevant counties were asked if they approved of adding table games to the racetrack in their area, and a majority of them did. (Arkansas, Rhode Island, and Iowa all enacted similar “coupling” legislation; but all three states later decoupled greyhound racing from casino operations.)

A fight to undo this legislation, and to end the Greyhound Fund, was already well underway in West Virginia when Delaware North bought Mardi Gras. The next year, in 2019, the company negotiated with kennel owners at another of their properties—this one in West Memphis, Arkansas, where decoupling legislation had recently been passed—to phase out greyhound racing over three years. A sense of their barely concealed exasperation pervaded my time with Florence, an Ohio Valley native with a vizsla and a German pointer at home, and White, whose eleven-year-old Doberman, Lola, was waiting for him back in Buffalo. Competition from casinos in neighboring Pennsylvania, Ohio, and Maryland was ever-stiffening. Doing business in West Virginia, it seemed, was a very particular thing.

Before leaving Wheeling Island, I sat beneath a cloud-streaked canopy of sky and sunshine on the concrete patio beside the track. At a nearby table, a man in sunglasses and a navy tracksuit with a Keystone Pennsylvania logo sat marking his program. His name was Fred, and he told me he’d been making the hour-and-change drive to this track from Pittsburgh, where he’d worked in the railroads for twenty-five years, three or four times a week since 1985. Even without the crowds of yore, Fred preferred the real thing to a simulcast. He once won two thousand dollars but said his average take is closer to two hundred. Fred seemed surprised to learn that this was one of the two last active greyhound tracks in the country—and a little concerned. As for the dogs, and the argument about whether racing did them harm, or good—or neither—that was a question, he told me, opening both hands as though to bless some invisible thing on the table between them, for other people to debate, and have opinions on.

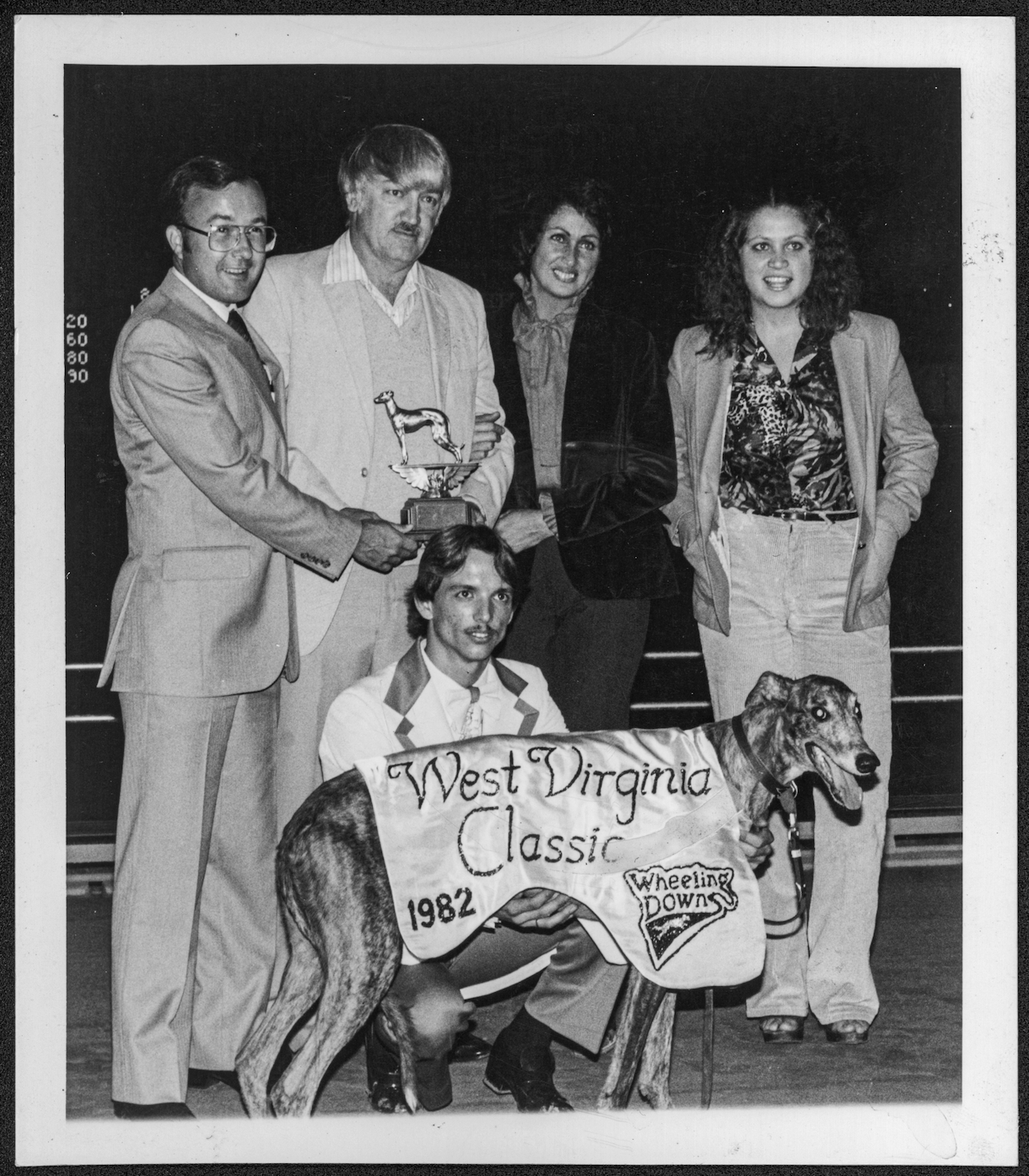

West Virginia Classic, 1982, Wheeling Downs Greyhound Racing. Courtesy the Ohio County Public Library Archives, Wheeling, West Virginia

I wondered if he had witnessed, in his nearly forty years of regular greyhound wagering, what I feared that afternoon: an accident, a collision, a fatal event.

At top speed, the greyhound inhabits its modern ensign: almost completely horizontal, a flying em dash. As the dogs cross the finish line, handlers a little farther down stretch a tarp across the track as a back-stop—but when the lure stops, for the most part, so do the dogs. (Among the responsibilities listed in a recent, $13.50/hour job posting for a Racing Leadout at Wheeling: ensuring that “injured or fallen dogs are safely removed from the track or going in the correct direction.”) In one of the final Wheeling races I saw, seven males competed against one female, SE Tilt a Whirl, who came in second. Fourth place went to four-year-old Good As It Gets, a dark brindle with white socks and a white tail-tip owned by a local breeder and kennel-owner named Steve Sarras. President of the West Virginia Kennel Owners Association and vice-president of the National Greyhound Association, Sarras owned six of that day’s racers; his kennel was home to ten more. Only a race’s top four performers would receive payouts derived from the Greyhound Fund. Most of that day’s $868,000 handle came from online bets made out of state, where most of the purse winnings would go as well.

I said goodbye to Fred, leaving him to the rest of the day’s betting. I wondered if he had witnessed, in his nearly forty years of regular greyhound wagering, what I feared that afternoon: an accident, a collision, a fatal event. A dog flying ass-over-teakettle and snapping its long equine neck. Three days prior, a dog named Klarity suffered a career-ending fracture during the fourteenth race of the day. Across the preceding two years, the state documented over a thousand greyhound racing injuries. In 2024, eleven dogs were euthanized, statewide, as a result of their injuries. Some dog deaths, like that of GF St Barts, who raced in a torrential downpour at Mardi Gras on April 5, 2022, are not noted in the records: because Barts died of a fractured skull on the track, and not at the hands of a state veterinarian, his death was not added to the tally. Video footage of that race has been removed from the track websites, which house a catalog of replays dating back to 2015. Footage of five of the sixteen races that resulted in a dog’s death between January 2023 and May 2024 cannot be found in the archives.

It is possible to know all of this and still stand transfixed by the spectacle of eight outlandish animals straight tearing up a track. The semblance of wildness—of pure, beastly instinct—crossed with a semblance of order, and control. As with horseracing, the risk of catastrophe is part of the rush. Much of the arguing about greyhound racing is bound by this cognitive gap, with one side describing a win-win in which dogs—clearly and specifically built to haul ass—do so for our enjoyment and economic gain, and the other citing the many problems, perversions, and cruelties involved in forcing one variety of a favored species to do our esoteric bidding—under the banner, no less, of honoring their natural instincts.

Why does a man gamble? What makes a greyhound run? Can freedom and compulsion ever coexist? How plausible is it to discuss what any domesticated creature loves, or hates, or truly wants to do? Put another way: When it comes to dogs, in particular, where might centuries of human intervention end and any trait or proclivity we might credibly call “innate” begin?

The puppy in my hands, nine days old and the size of a Kondor potato, had been put there by Steve Sarras not long after I arrived at his breeding farm in Windsor Heights, eleven miles up the Ohio River from the Wheeling track. Shortly after we shook hands, Sarras had brought me into the small, barn-like structure where new litters whelped and newly weaned pups were housed alongside brood moms done with their weaning, and dogs either sitting in time out or recovering from their time-out-related wounds. In a stall toward the back, a nursing pup dropped an unceremonious foot or so to the ground as its mom rose, panting and wiggly, to greet us. Standing inside that stall with Sarras, I smiled absently each time he suggested I pick up a member of the nine-puppy litter—sired, as is standard, via the sperm of some long-dead racing legend. It seemed unwise in the way a hit of Ecstasy on the job would be unwise. Eventually, he thrust one forward, rendering me insensible to everything but the boneless, silky weight in my palm and its blind, undeterred clamor for food, for warmth, for its long-bodied mom.

At fifty-three, tall and broad in his black t-shirt and beat-up jeans, with a beard to match his ring of close-cropped, salt-and-pepper hair, Sarras was forthright, warm, and practiced in his brief. Demonstrating the health and well-being of his wares had become part of Sarras’s job in recent years. In the ninety or so minutes we spent at the farm where he and a small staff, including his college-age son, Nikolas, look after about seventy-five dogs—all, except for the mothers, under twelve months old—Sarras spoke even of his sense of besiegement with the calm of a skilled politician. Proud of the work he had done to develop and maintain what had been a derelict property before he purchased it in 2021, he emphasized the circulation of the money he received from the Greyhound Fund back into various communities, including this one. He is often on the road, ferrying former racers to adoption agencies throughout the South and Midwest especially. Adoption programs ramped up in the early 2000s, as evidence of the routine killing of failed or used up dogs came to light. One such case involved the discovery, in 2002, of the burial of what was estimated to be up to 3,000 greyhounds on the Alabama property of Robert L. Rhodes, a security guard at a Florida track. For decades, owners had paid Rhodes ten dollars a head to transport, kill, and bury their unwanted dogs. At sixty-eight, Rhodes told a reporter he had been putting bullets in greyhound brains his entire adult life—humanely, he insisted. They didn’t feel a thing.

As Sarras and I stood in the kennel’s entryway, giant blocks of frozen raw meat sat thawing in the twin sinks between us. Having drifted inside, Nikolas loomed behind my right shoulder as Sarras spoke of his father, Manny, who emigrated from Greece to Massachusetts in 1969. Connections he made at Raynham-Taunton Greyhound Park, the track near his Brockton home, led Manny first to purchase a few dogs, then to build out a kennel and breeding farm. Both of his sons helped out growing up, as Manny saved to realize his dream of sending them to college. Despite having studied to become a physical therapist, Sarras, newly married and contemplating kids of his own, decided racing was the safer bet. Though he joined the family business full-time some years after the industry’s 1992 peak, when seventy operational tracks nationwide took in $3.5 billion in betting, it offered a steady living through the period of decline that preceded the 2008 general election, when a referendum on whether to ban racing appeared on the Massachusetts ballot. The result was decisive: fifty-six percent voted yes. Soon after, a commentary published in the Boston Herald suggested, with some bitterness, that voting had split along class lines: the richer the town, the softer it could afford to feel about the hounds. It went seventy-thirty in tony Concord, for example, “where gambling is not what fuels dreams, where chocolate labs sleep on beds from L.L. Bean.”

The Massachusetts phase-out lasted thirteen months. Sarras and his brother decided to try their luck in West Virginia and Florida, respectively. Manny, Sarras told me, was working to reverse the vote until the day he died, at age sixty-nine. “Nik, when did he die?” he asked his son, still standing behind me.

“October 20, 2009.”

“He remembers the day,” said Sarras, his voice tight. “I’ve blocked it out.”

Greyhound breeder Steve Sarras with some of his dogs on his farm in Wellsburg © Chris Schulz/West Virginia Public Broadcasting

Sarras declined to show me his eighty-four-dog kennel in Beech Bottom, four miles away, where all of the Wheeling Island racers are housed, about a thousand dogs in total. (Roughly a thousand racing greyhounds are now bred in West Virginia each year.) Regulated by the state, the kennels are surrounded by security fencing and have what Sarras described as a rigorous vetting process for visitors—too rigorous, he insisted, for us to bother. We had left the kennel and were walking the grounds where older puppies live in a couple dozen shacks, a few dogs per shack, each one stationed at the far end of a narrow, fifty-yard turn-out pen. The late-afternoon sun gave a liquid-gold light. Cluster after cluster of dogs, frantic and sweet-faced, scrambled to greet us as we passed, their long, snuffling noses seeking our fingers through the fence.

At twelve months, Sarras moves the dogs out of state, to places like Kansas and Oklahoma, for at least six months of training. He described this process as focused on desensitizing the greyhounds to the noise and feel of the starting boxes, teaching them how to run straight and take corners, and using a lure-like contraption made of squeaky toys, car wash mitts, and two-liter soda bottles to spark their excitement. As with every other aspect of greyhound racing, allegations of cruelty and mistreatment surround these training practices—specifically the use of live lures to entice the dogs into a frenzy, creating the Pavlovian imprint to be triggered by mechanical lures on the track. Footage recorded by an anti-racing activist between 2020 and 2021 shows trainers in various states, including Oklahoma and Kansas, using live and dead rabbits to incite the greyhounds. One video, taken in Kansas in July 2020, depicts Ursula O’Donnell, one of several people arrested in connection with the case against Robert L. Rhodes in 2002, pulling a live rabbit out of the back of her red pickup truck, tossing it into a field, and releasing several greyhounds to give chase. The dogs, all muzzled, quickly converge upon and maul the rabbit before dispersing; the rabbit eventually rights itself and hops away. O’Donnell’s property sits two miles from the National Greyhound Association’s headquarters.

The work of running and defending his business, Sarras emphasized, is never-ending: “If you followed me around for a week, you’d be like, Why do you do it?”

Asked about practices like live-lure training, the confinement of dogs for up to twenty-three hours a day in wire enclosures stacked inside the racing kennels, the use of anabolic steroids (methyltestosterone) to prevent estrus—and therefore, anti-racers argue, keep female racers competitive—and the feeding of grade 4D meat (unfit for human consumption, it comes from cows found dead, dying, diseased, or disabled), Sarras invoked the logic of incentives, good business, and basic common sense. Treating his investments well—some dogs are bought and sold for up to thirty thousand dollars—is in his best interest. In their pursuit of a steady flow of donations from people who don’t know any better, Sarras claimed his opponents slant the facts to inflict maximum damage and erase mitigating context. In refuting their charges, he worked sometimes to restore that context, and sometimes to blur it even further: a bitch in heat would create havoc in a kennel; women’s birth control is also technically a steroid. The Greyhound Fund is not a subsidy because it doesn’t draw on taxpayer money; removing it hurts the animals and all the people employed in their care. The meat is cheaper, yes, but the savings aren’t worth a kennel full of sick dogs; 4D meat is also a pet food staple. Live-lure training is illegal,and one of the alleged offenders never produced top-tier racers, so it doesn’t even work. His dogs are demonstrably fit, happy, and ripped as hell: if that’s what twenty-three hours a day in a cage gets you, you can sign Sarras up. It may be true that racers occasionally stroke out, have seizures, or drop dead of a heart attack at the finish line—that’s also, not for nothing, pretty much how his father died. Here and then gone, just like that.

The work of running and defending his business, Sarras emphasized, is never-ending: “If you followed me around for a week, you’d be like, Why do you do it?” I repeated the question back to him. “You just love the dogs,” he replied. “You just love the dogs.”

As we finished our tour of the compound, Sarras noted a military plane overhead, returning to the air force base nearby. “Art’s son is actually stationed out there,” he told me. “He’s like a helicopter pilot.” We had discussed Art Thomm earlier, when I asked Sarras about the growing role of lobbying in his line of work. Having lobbied himself, especially in 2017 and 2020, when anti-racing bills were last put up for a vote in the state legislature, Sarras realized the West Virginia Kennel Owners Association needed a bigger gun after the other two states still racing greyhounds post-2020, Iowa and Arkansas, both closed their tracks in 2022. A former state lobbyist for the National Rifle Association, Thomm is well-connected in West Virginia and beyond, a solid ally in what Sarras characterized as a “David versus Goliath” kind of fight. About a system that requires lobbyists, and their considerable expense, Sarras is resigned: he didn’t make the rules, or the First Amendment. The job, as he sees it, is to counter the propaganda pumped out by what he calls the antis, animal welfare and anti-racing groups. Believe their lies, Sarras tells legislators, “and you’re going to destroy your state.” The shadow of his father’s sudden death, and the anguished final months of Manny’s life, are palpable in these moments. Sarras promised to show me a letter from a shuttered Massachusetts racetrack. “You’ll see the carnage that they left behind—how many jobs lost, how many state dollars lost.”

Though he never mentions it by name, when Sarras speaks about the antis, the “they” who are hoodwinking the public, warping the truth, and wordsmithing to inflame and elicit a negative response, he is almost certainly referring, foremost, to the Massachusetts-based nonprofit GREY2K USA. Co-founded in 2001 by Christine Dorchak and her husband, Carey Theil, GREY2K has done more to eradicate greyhound racing across the United States than any other organization. It is because of their organizing, fundraising, and coalition-building that the question of whether to abolish greyhound racing was added to the Massachusetts ballot in 2008. In Brooklyn Goes Home, their co-authored 2023 book, the couple describes amassing thousands of volunteers to gather the 150,000 signatures necessary for their ballot initiative to move forward, only to lose the vote and start the process all over again. Having won on the second try—the group’s first major success—they claim the defeated industry refused their efforts and those of the state to help adopt out the dogs and retrain track workers. Theil, who achieved national chess master status in his twenties, retrieved the sign from Wonderland Greyhound Park, just north of Boston, which ran its last race in September of 2009, and hung it in his Arlington office. It is GREY2K that hired the investigator responsible for the live lure videos.

I wondered if Sarras conceded anything to the antis, if they had ever made a solid point. “They’re a lot better at, you know, impressing the general public than we are,” he replied. “But then again, I don’t have time to do that. Look how hard it was for you to have a sit-down with me—because I’m taking care of dogs. I’ll guarantee you I take in a fraction of what they take in and I’ll guarantee you I give more money to adoption than they do, and more money to charities in local communities than they do. I do more in terms of taking care of dogs than they do.”

Before I left, Sarras, standing in the long driveway parked with several kennel trucks, his hazel eyes squinted in the sun, told me he sees this as a lifelong fight. “And they want it that way, too. Put it this way: if there’s no racing in West Virginia anymore and they’re successful here, where are they going to get money from? They’re going to have to go—and they’re already doing it now—overseas, linking up with groups out there because…there has to be a cause. Now that cause could be fabricated. I mean, did you see any dogs that looked abused or neglected to you? I don’t know if you saw any at the track. Maybe you did, maybe you didn’t. But they all have pretty good lives.”

Earlier, in the whelping kennel, Sarras had shown me a picture of Camel, the pit bull mix he adopted at the beginning of 2023. “That dog was abused. That dog was neglected,” he said. In the pound for over a year, Camel—fearful, anxious, and a biter—had been returned several times. Sometimes aided by a phlegmatic greyhound, Sarras has worked daily to build Camel’s confidence, earn his trust. Did he really, I wondered, need another dog in his life?

“That’s what everybody says,” Sarras replied.

The dry, powdery snow that had covered Charleston, West Virginia, overnight was still falling the morning I met Carey Theil at his hotel beside the Kanawha River. The landscape had been remade in the three months since Theil’s last trip to the state capital, just before the 2024 election. It might still be the case, as he told me during our first conversation the previous summer, that West Virginia is “barely a democracy,” not far removed from “just guys running around with bags of money,” but the new old boy in power, incoming governor Patrick Morrisey, appeared more receptive to GREY2K’s overtures than the one he had replaced. Some of that receptivity was fortuitous: one of Theil’s two lobbyists, Conrad Lucas II, is also a member of Morrisey’s transition team. Sitting in the lobby of the Courtyard Marriott with an iced coffee, Theil—fair, bespectacled, and wearing the same tan suit in which he, together with wife Christine Dorchak, recently gave a TED Talk—exuded a balmy confidence. The November visit had included a meeting with someone “who would have a big say in the debate going forward,” he told me, declining to give a name. “You know, I mean,” he added, smiling. “It wouldn’t be hard to guess.”

Political gamesmanship came perhaps a little too easily to forty-seven-year-old Theil, a chess prodigy whose Oregon youth involved both obsessive study of that game and animal rights activism alongside his mother, Connie. In the past, his work as both a spokesperson and a tactician for his cause provided an outlet for the cutthroat competitor lurking behind a rather mild exterior. He recalled, with some embarrassment, the pleasure he took in making an Iowa attorney fly to Boston so that they could negotiate at GREY2K headquarters, beneath the old Wonderland sign. These days, Theil speaks of his ego as one among many wily opponents. Dorchak, a Boston native who devoted her life to animal welfare after her Black Russian Terrier, Kelsey, saved her life in 1992, came to focus her efforts on greyhound racing. She entered law school in 2001, studying at night to better counter an industry wrapped in legal and governmental protections. While Dorchak drafts bills, handles legal briefs, and secures fundraising (between 2019 and 2023, GREY2K took in an average of $1.1 million per year), Theil gets to do what he calls “the fun stuff”: execute a ground game against the cadre of legislators, lawyers, political operatives, and racing folk he has tangled with for almost twenty-five years.

Florida was Theil’s white whale. For ten years, he came up short against the state where dog racing had been most lucrative and where its interests were most entrenched. “They were so powerful,” Theil told me. “And so good at making the levers of power work to their advantage, that the only way we were ever going to win was somehow to adapt and grow. As an opponent, they transformed us.” Tactics that Theil had rejected early on, like emphasizing how the dogs live, became go-to material. Bipartisan support was key, including from figures like Lara Trump and Matt Gaetz, both of whom supported the ballot initiative, which passed with sixty-nine percent of the vote. At that time, Dorchak called Florida “the silver bullet in the cruelty of dog racing”; seven years later, one state and two tracks remain.

“I get a little depressed every time I come here,” Theil told me. “You really feel like this is a golden jewel that the rest of the country is overlooking.” Even before the Florida win, it looked like GREY2K had West Virginia in the bag: A 2017 bill to discontinue the Greyhound Breeding Development Fund passed in both the House and the Senate, only to be vetoed by then governor Jim Justice, a registered Republican who ran and won as a Democrat. Seven months after taking office and four months after vetoing the anti-racing bill, Justice re-declared himself a Republican during a rally with Donald Trump. No one I spoke to could explain the veto, beyond a statement citing concerns about tourism and job retention from Justice, a coal mine heir who Forbes recently reported owes business debts exceeding one billion dollars. In 2020, then West Virginia Senate president and GREY2K ally Mitch Carmichael introduced a bill that would both eliminate the Greyhound Fund and decouple live dog racing from casino operations. In an unusual turn, Carmichael faced opposition from his own majority whip, Senator Ryan Weld, who represents District 1, home of both Wheeling Island and the Beech Bottom kennels. “We had radio ads, we did a huge grassroots push, lots of constituent contacts,” Theil told me. “I was here a lot. And Ryan Weld basically told Mitch, ‘I’m going to beat you on this.’ They had a floor fight, Ryan crushed him, and the issue sort of went dead for a few years.”

Multiple anti-racing bills have been introduced since 2020, all of which have died in committee. A lead sponsor of two of those bills, former House delegate Chris Pritt, blamed their failure on the “outright…I guess you could call it corruption” that has maintained what he called a state subsidy for a failing industry. Based in fiscal pragmatism, his position was not insensible to the dogs: Not only was West Virginia barely recouping the expense of regulating the industry, but “the optics of this are just terrible. To me it’s a real stain on the state.” Speaking to me from Wisconsin, where he was attending the 2024 Republican National Convention, Pritt described the maddening roundelay that had been his time in an overwhelmingly Republican legislature, a body beset by lobbyists and vested interests. After a failed Senate bid, he was set to return to his law practice. Several hours after I spoke with Pritt, Governor Justice took the convention stage alongside Babydog, his English bulldog. Babydog, Justice told the delegation, predicted a November sweep of the legislature and the re-election of Donald Trump. Indeed, Justice himself was elected as the first Republican in his West Virginia Senate seat since 1956, replacing Joe Manchin. In Wisconsin, the crowd had chanted Babydog’s name. “She makes us smile and she loves everybody,” Justice boomed. “And how could the message possibly be any more simpler than just that?”

Greyhound race at Wheeling Island, West Virginia, 2008. Photograph courtesy glindsay65 via Flickr, Attribution-NonCommercial-ShareAlike 2.0 Generic

As we spoke about the new governor and the roulette wheel of political influence, Theil related a recent story he’d heard about his opponents. A gossipy bit of business—the particulars of which I couldn’t confirm—the story’s interest lay in its capture of the ethical and semantic gray areas within which so much of this fight has played out—amid debates about how to define the word subsidy, the difference between a crate and a cage, and what qualifies as animal abuse. Theil has had to get comfortable with one foot inside that space, both to better know his opponents and to keep their humanity in view. When I told Theil that Sarras believes GREY2K is driven by greed (“Look at their financials,” Sarras told me. “See how much money they spend on dogs. It all goes to lobbying and legal.”), he became very still.

“So, I don’t own a home. I have no savings. But I don’t care about money. I’m not motivated by that at all. I also think it’s deeply ironic: this is a story of how dog people took on a multi-billion-dollar gambling industry and won. If this is a David and Goliath story, it’s not in the way he thinks it is. Now, in fairness, I do think the dog men were never—it was always the track owners that were, you know, the heavy muscle. And I think the dog men were hurt by that relationship in a lot of ways. And I get it. I do get it. I think Steve… I think it sucks. He’s done this his entire life. His father did it, his grandparents did it. His son wants to do it. And it’s not just that it’s going away—it’s society telling him that his family tradition is cruel. To have the public turn against him, to have the track owners turn against him—it’s a bitter, bitter place. It’s a bitter pill to swallow. So, I have a lot of empathy for him, I do. And—I’ve felt this for years—but the fact that they don’t truly see who we are is very much to our advantage. I mean, know your enemy, right? Know yourself and know your enemy. And I want to be careful here because there’s ego in this, but I do think it’s true that we have a much clearer sense of them than they have of us. I think they’re telling themselves a little bit of a fairy tale, to put it bluntly. It’s easy for them to tell themselves that we’re these greedy animal rights people who are coming in, and everything we’re saying is lies. But I’ll tell you what: Steve Sarras kills dogs. If you could actually see all of his years in the industry, you’d see live-lure training and, I suspect, you’d see some dog killing. So, you know.”

The Greyhound Protection Act . . . opens by stating that the greyhound is the only dog breed mentioned by name in the Bible.

GREY2K’s current strategy for closing out the dog racing industry in the United States, Theil told me, is three-pronged. The Greyhound Protection Act, a federal bill that amassed eighty sponsors after first being introduced in 2023, opens by stating that the greyhound is the only dog breed mentioned by name in the Bible. (Proverbs 30:29, which lists various creatures with attributes their creator finds pleasing; greyhounds are described, in the King James translation, as “comely in going.”) “It’s hard to handicap, because Congress is such a mess,” Theil said. “But it’s very real.” Then there is the intricate logistical fight to ban both simulcasting and internet betting on greyhound racing in the various states that allow and enable it. During a visit to Florida the week before I met with Theil, I stopped in at the Palm Beach Kennel Club, where a Sarras dog named Rob Gronkowski once won thirty-nine of his fifty-three races. Though the track is abandoned, I watched a Wheeling Island race on a ceiling-mounted TV inside, trying not to block the view of the man behind me murmuring encouragement to his pick.

Then—again—there is West Virginia. “I think we have the best chance this year that we’ve had in years,” Theil told me. Because of the state’s closed legislative system, “just one guy, quite frankly,” has been able to quash their efforts to undo racing legislation for half a decade. However various his motivations, according to Theil, Senator Ryan Weld “genuinely believes in his position,” and has used his personal conviction to rally a small coalition. “It’s just politics, it’s not the issue at all,” Theil said. “But they have outplayed us. Their champions in the legislature have more passion than ours, they’ve made smarter moves.” The House judiciary chair has not given any of the bills GREY2K has helped architect over the last few years a hearing in committee, Theil suspects, because of Weld’s intervention. “If that’s true, and I think it is, that was very clever, very well played.”

A recent turn in Weld’s political fortune (“He backed the wrong horse” in the previous month’s bids for Senate leadership, Theil said, and “now he’s a backbencher”) has opened a portal in the legislature. Even Delaware North, according to Theil—which is in regular communication with GREY2K, but only through intermediaries—is making a more direct push to the state. By the close of our conversation, another two inches of snow had fallen. The end, and not a mirage of the end, Theil felt, was finally in sight. A new anti-racing bill was introduced in the West Virginia House two weeks after we met. The smart move for Sarras, he told me, would be to negotiate a deal with Delaware North similar to the one they struck with Arkansas kennel owners. If he doesn’t, “we could very easily just run over him in the legislature, and have it done on terms that are not good for him.”

Earlier, I had wondered if Sarras’s avowed devotion to his dogs bore some relation to the rancher who tends lovingly to his cattle before sending them off to slaughter. The kind of farm-bred sensibility that city dwellers, eating Shake Shack burgers in their fancy leather boots, find increasingly alien, even abhorrent. Yet I saw a rough corollary in Theil’s description of crossing grassroots strategy with political sophistication; the challenge of trying to outwit systemic corruptions without replicating them; the discomfort of cutting a deal that benefits the horseracing industry in order to snuff out the one racing dogs; the personal and social hypocrisies that riddle our slow deciphering of animal rights. The reward of navigating the mess that surrounds it, he told me, is the purity of his narrow purview, the gift of caring about something more than himself, and the added bonus of having other people—like the chess opponent who looked him up before their tournament game the previous weekend—see you and your work as decent, humane, worthwhile. Theil and Dorchak, having grieved hard for their past dogs—including the greyhound, rescued from a notoriously brutal track in Macau, whom they memorialize in Brooklyn Goes Home—currently share a home with four black cats.

Headed for the West Virginia State Capitol, where he hoped to take a couple meetings, Theil would walk the same halls Sarras has roamed many times, over many years. Though they have never spoken, the two men, Theil told me, would be intertwined for life. I repeated that I didn’t doubt Sarras when he talked of his love for the dogs, that the difference between loving something and believing you do is almost impossible to parse. “I think I agree completely,” Theil replied, setting his drink down between us. “One hundred percent.”

It took two weeks in the West Virginia House of Delegates for Ryan Weld to know he wanted out. A native of Weirton, a former steel mill town north of Wheeling, Weld, a junior in college on 9/11, joined the U.S. Air Force shortly after graduating. He moved to Washington DC in 2003 and worked in intelligence operations there and elsewhere until his 2010 deployment to Afghanistan. Determined to move home after his return, Weld decided on law school, attending night classes in Pittsburgh and working in the Brooke County prosecutor’s office during the day. On the cusp of finishing his degree, Weld got a call from a political contact looking to recruit the then thirty-three-year-old for a state House run. His first session, in 2015, also marked the first time in eighty-three years that Republicans held a majority in the legislature. After two weeks observing the stultifying pace at which issues were argued in that body, especially as compared to the sleeker, more efficacious one across the rotunda, Weld made a plan. “When I was elected to the Senate two years later,” he told me, “I became the first Republican senator from Brooke County in exactly a hundred years.”

I had taken my time wandering the dim halls of the capitol, a 1932 build with a vaguely ecclesiastical, golden-plated dome, before reaching Senator Weld’s office. One bank machine outside the Treasurer’s office, two taxidermied black bears, and a corridor filled with governor portraits featuring slight variations of the same old, white, male face marked my path to the doorway through which Ava, Weld’s fawn brindle greyhound, could be seen lounging on a giant dog bed. She was racing under the name Dr. Disrespect on the late 2019 evening that Weld first visited Steve Sarras’s Beech Bottom kennel. “She is very disrespectful, as you can see,” Weld said of the dog in the wide collar, printed with tiny, hanging sloths, whose teeth chattered softly—greyhound for yespleasethankyoumore—when I stroked her neck where she lay. A semi-regular at the capitol, Ava has served as a silent ambassador for the industry and a stress absorber for the staffers who stop by for mini-spoon sessions in her bed.

Upright and trim in a navy suit and red tie, Weld has the formal but unfussy manner befitting, almost exactly, a product of the military, politics, and practice of the law. We sat at a table in the office he’s occupied for several years, a similarly formal but unfussy space. Football helmets from District 1 high schools line multiple shelves on walls otherwise filled with pictures. One depicts the second of his three dogs, a rescue named Trudy, sitting in his office chair; another captures the moment former West Virginia governor John “Jay” Rockefeller IV hoisted up baby Weld during an early 1980s campaign stop. I had tried for several weeks to reach Weld the previous summer, without success. When I mentioned this to Sarras, at his farm, he had pulled out his phone, called Weld as I stood there, and made the connection.

“I’ve been around mistreated dogs before. Those were not mistreated dogs,” Weld told me.

Though he calls Mitch Carmichael “one of my closest friends down here to this day,” when the then Senate president made ending greyhound racing a priority for the 2020 agenda, Weld, having voted against the 2017 bill, decided to do some research—specifically to see for himself “how these dogs live, how they’re treated, their environment.” After a House delegate put him in touch with Sarras, Weld and his wife Alex, both self-described animal lovers, were cleared to visit Beech Bottom, which they found clean, well-lit, and better maintained than the average shelter. “I’ve been around mistreated dogs before. Those were not mistreated dogs,” Weld told me. Encouraged by Sarras, they brought several hounds out of their enclosures, the first of which, almost two years old according to her ear tattoo, held fast to them for the next several hours. The couple mused about bringing her home someday; Sarras told them he retires most racers between four and five years old.

Two months later, Weld stormed the Senate floor with accusations of misinformation spread by GREY2K. He impugned a recent poll, funded by the group, in which a majority of the four hundred registered West Virginia voters they polled said they opposed the Greyhound Breeding Development Fund, and he disputed Carmichael’s claims, drawn from ten-year-old data, about the prevalence of dog deaths at the state’s two tracks. In the press, he and House delegate Shawn Fluharty emphasized GREY2K’s outsider status and accused them of buying votes in the legislature. Between 2020 and 2023, Weld and Fluharty received over $25,000 in combined campaign donations from Sarras, his wife, and Nikolas. (The family donated $26,000 more to other candidates in the same period.) Two weeks after Carmichael’s bill “went down in flames,” Weld got a call from Sarras: Despite having recently won a Wheeling Island race, Dr. Disrespect was ready for adoption. The couple named her Ava after watching a documentary about Frank Sinatra (a greyhound fan once married to Ava Gardner) and admiring the diva-like way that, upon first entering their home, she sauntered past her more chaotic and extremely displeased new dog-mates.

By his own account, Weld’s position on racing still rests entirely on his belief that it doesn’t harm the dogs. “I think if I was a legislator thirty years ago, twenty years ago, I might not have come away with the same feeling,” he told me, adding that there is more regulation now, and more policing. And there is his personal relationship with Steve, an association that convinced him Sarras “truly cares about the dogs.” Only a revelation of widespread abuse or neglect, Weld told me, could change his mind. When I pointed out that his Republican colleagues drafting bills were more focused on the math—a failing business model and possible redistribution of the Greyhound Fund—Weld launched into his own talking points about what does and doesn’t qualify as a subsidy, and the referendum question that voters in the relevant counties approved back in 2007. (“The question was, ‘Shall we have table games at a racetrack?’ Not, ‘Shall we have a racetrack at the casino?’ And so I think you’d face a little bit of a constitutional challenge there if you just said, we’re not racing anymore.”) Weld sees his colleagues as mis- or under-informed: “GREY2K has gone after a number of legislators who took the same position that I have, but they’ve never come into my district. They know it’s a losing issue, because of the history of greyhound racing and racing in general in Ohio County.”

Weld ended his campaign for state attorney general in late 2023, citing fatigue with a process that, he said at the time, “sometimes requires candidates to compromise their core principles for political gain….The never-ending asks for campaign contributions, as well as the constant deal-making can really wear on a person’s conscience.” The state-wide race, he told me, was all fundraising calls and outside agendas, and none of the small-pond stuff he loved about his Senate campaigns: door-knocking, parades and state fairs, stopping into McDonald’s to join the ubiquitous “bunch of guys, like an old yentas club sitting there, drinking coffee.” Former state auditor and House delegate John McCuskey went on to win that race, replacing now Governor Patrick Morrisey, who had served as attorney general since 2012. When I mentioned his power in the state Senate, the influence that has made him the main obstacle to abolishing greyhound racing in West Virginia, Weld’s expressive face fell mute before he spoke. “I have one vote in this building,” he said, adding, “I just got my ass beat on an amendment this morning.” He noted the recent Senate leadership change and erasure of his senior status with the rueful equanimity of a man better acquainted than he once was with what he wants and what he is able to do. Like the curtailing of his statewide ambitions—like Carmichael’s 2020 whipping and departure from office soon after—it’s the kind of thing any competitor must at least pretend to treat with philosophic detachment. Which is itself a luxury, perhaps, that West Virginia politicians know better than most.

Between handshakes and greetings in the capitol hallways, where the Wheeling University women’s rugby team moved about as a herd—their leader clutching a national trophy—Weld showed me both chambers and the recently completed murals of various historical scenes inside the dome. Conceived as part of the building’s original design, arguments about how to fund the murals held up the process for over ninety years. A lawsuit is now underway concerning the apparent addition of Babydog, Jim Justice’s canine sidekick, to a pastoral scene at Seneca Rocks.

Before we parted, I asked Weld, who called racing handle numbers “still pretty high,” what he thought of Sarras potentially striking a buyout deal with Delaware North. “How I see it is they are largely in control of their own destiny,” he said. “Whatever that might be, I’m going to advocate for it. If Steve called me tomorrow and said, ‘We’ve decided to shut her down and phase it out in the next three or four years,’ I’m not gonna tell them that they can’t. That’s their business. It’s their industry.”

He’d keep fighting for the dogs, who wag their bullwhip tails after each race.

The gaming floor at Mardi Gras Casino & Resort, fifteen miles outside of Charleston, West Virginia, was just shy of humming on a Tuesday night. As I passed a bank of Wonder Woman slot machines, a collective cry rose from a nearby blackjack table. The fun stopped at the threshold to the Big Easy Lounge, a viewing bay overlooking the outdoor track. Several unmanned table game kiosks prefaced half a dozen empty rows of graduated seating. A selection of mid-aughts pop and indie-sleaze echoed against the filthy glass, beyond which the surface of two misshapen ponds inside the racetrack appeared to shiver. It was cold, twenty-six degrees. As the dark set in past six o’clock, when the first of the evening’s fourteen races was set to start, the pockets of shadow that alternated between wide pools of stadium light began to deepen.

Back at his desk in Arlington, Carey Theil would review each one of these races, looking for clues, for injuries, signs of a race gone wrong. The night I was there, he would later note, marked the lowest daily handle in months. Two days later, evidence of a fall taken by a first-time racer named Superior Layla would go missing from the replay footage; the next week, two dogs would sustain career-ending injuries on the same night.

Access to the outdoor trackside space was closed for the winter. The woman in chunky, leopard-print glasses at the casino floor security desk had been unsure if the dogs were racing at all. I walked back to the viewing bay as another pack of racers was led out to their gates. Several Sarras dogs were in the night’s running. A couple months before, Sarras had texted me a spreadsheet without comment: nine years of GREY2K financials, alongside those of PETA, the Humane Society, and the ASPCA. He’d keep fighting, he told me at the farm, for the workers who dedicate their lives to this job, who won’t be as happy or earn as much doing anything else. He’d keep fighting for the dogs, who wag their bullwhip tails after each race. You don’t see too many of them, he noted, getting dragged to the starting box.

On the track, the dogs did as they had been bred and trained and then prompted, at least once each week, to do. At one point my attention drifted to a lone handler who stood near the finish line, directly below me, as the next race neared its start. I fixed on the outline of his turned back, the black hood of his sweatshirt pulled up, the red leash hanging from his neck. Propped against the railing, arms crossed against the cold, the young man looked not to the starting gate but straight down at his feet, one slung over the other. The moment stretched out, distorted by burdens both plain and hidden from sight. It seemed to continue, unbroken, as eight muzzled greyhounds streaked past.

Support the Oxford American

The Whiting Foundation will double your donation—up to $20,000.

Your donation helps us publish more work like the article you're reading right now. And for a limited time, every gift will be matched up to $20,000 by the Whiting Foundation.

Prefer a subscription? You'll receive our award-winning print magazine—though subscriptions aren’t eligible for the match.