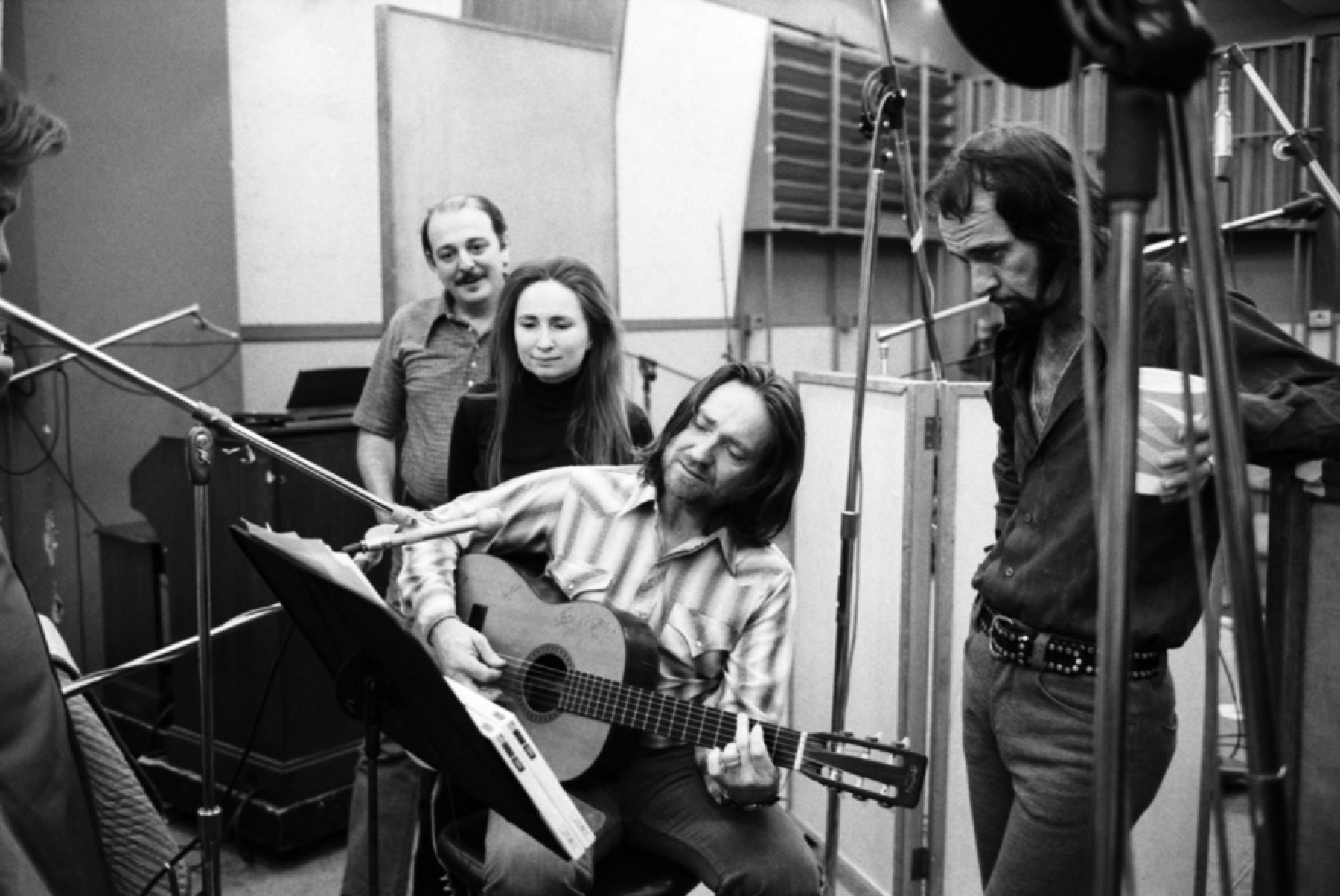

Paul English (right) at Willie Nelson's 1973 Atlantic Session. © Estate of David Gahr / Getty Images

Watching Willie’s Back

By Joe Nick Patoski

Paul English was talking about breaking someone’s legs, cheerily using the threat as a means to get to the punch line of a story. The four men listening to him in the back of the touring bus hung on every word—because it was Paul, because it was very difficult deciphering his nasal mumble filtered through a twang, and because whatever he said was likely to be true.

“I told Lana we could do something,” Paul was saying. “We could break his legs. We have to do something to him. We cain’t go and leave him walking. We’d of done that to him. That’s nothing.”

He was discussing the shoot-out at Ridgetop back in 1970, just outside of Nashville, when Willie Nelson and Paul English defended a house full of family against Willie’s daughter’s husband and his gun-toting brothers, one of many larger-than-life incidents that have been burnished into legend over the course of the career of Paul English’s boss and best friend, Willie Nelson. In this particular story, Willie’s daughter Lana’s husband, Steve, had hit her, prompting Willie to go over to their house and slap Steve, pissing off Steve so much that he and his brothers drove over to Willie’s house and started shooting. The altercation ended with Paul firing .380-grain bullets from his M1 rifle into the bumper of Steve’s car to “get him to go on, goodbye.”

When Steve returned to apologize the next day, Paul told him he was glad he had kept driving away. “Otherwise, I would’ve had to aim to kill, rather than shoot to miss,” Paul said in a low growl that suggested a ruthless predatory killer, followed by a sharp cackle. Everyone hearing the story laughed. But Paul wasn’t kidding.

For almost fifty years, Paul English has spent his nights literally watching Willie Nelson’s back, as his drummer. The rest of the time he has functioned as Willie’s more figurative back—a job that runs 24/7.

From the drummer’s chair, English sees everything, just like the catcher on a baseball team. His oversight goes far beyond maintaining the odd, minimalist beats that guide Willie’s music. For him, the drummer’s chair is the perfect perspective for running the most storied touring organization in country music. More important than being Willie’s drummer, or his best friend, is Paul English’s combined role as the road boss of Willie’s traveling company, tour accountant, protector, collector, and enforcer, roles embellished by his proud past as a hoodlum, pimp, and police character. For all the good vibes that the Red Headed Stranger imparts at his Fourth of July picnics, Farm-Aids, and wherever he plays “On the Road Again,” there’s an understanding shared by one and all in this band of gypsies: Mess with Willie Nelson and the next thing you’ll see is the wrong end of a gun held by the Devil himself, Robert Paul English.

Say what you want about economics, ethics, efficiencies, legalities, and proper ways of conducting commerce in the world of entertainment. Anyone who’s survived six decades in the music business understands the value of having a police character in your organization. As Willie explained to an associate who’d wondered why he kept an asshole like Paul on the payroll, especially when he couldn’t keep time as a drummer: “He’s saved my life.” More than once. Besides, as the singer Delbert McClinton has observed, “Everyone in this business needs an asshole.”

That sort of explains why the asshole drummer who can’t keep time was once the highest-paid sideman in the business, getting 20 percent of all of Willie’s action as well as a fat salary for drumming and for doing the books, which he has done since he signed on in 1966.

Those songs, such as “Nightlife” and “Family Bible,” that Willie famously sold for fifty bucks a pop, giving up his publishing rights? Paul got them back.

No telling what his method of persuasion might have been, but with Paul there is always, always—to this very day—the veiled threat of violence bubbling under the surface. Often as not, the perception is tied to Paul’s fondness for guns, at least one of which is always somewhere on his person.

Largely thanks to Paul, Nelson was able to survive on the rough and rowdy honky-tonk circuit traveled by Nashville recording artists in the 1960s. He was also instrumental in running the road part of the business when Willie ascended to one-name superstar status in the 1970s and 1980s.

At eighty-two, a year older than Willie and four years off a minor stroke, Paul has slowed down considerably. But in the musical subgenre known as outlaw music, where country and rock have mixed it up ever since Waylon and Willie and the boys stepped forward, Paul English is that rare bird who really is an outlaw, a hoodlum-made-good as sideman, sporting so much character for a character that his boss wrote not one but two songs about him: the autobiographical “Me and Paul” and “Devil In A Sleeping Bag,” complementing Leon Russell’s tribute, “You Look Like the Devil.”

As his son Paul Jr. observed, “If you’re writing songs about shooting people, it’s nice to have a guy who’s shot people up there onstage with you."

The high cheekbones, long sideburns, thin beard and goatee, the widow’s peak and slicked-back hair framed by designer glasses (whose tinted lens mask a glass eye) all telegraph Beelzebub, despite his age. Although he no longer wears the black satin cape with red lining that was once his trademark on stage, and he doesn’t appear to carry his “bidness” in his sock anymore, darkness shrouds Paul’s lanky frame—black shirt, black slacks, black hat, and black boots. It’s his favorite color, he’ll tell you.

Paul English at Willie Nelson's Atlantic Session. © Estate of David Gahr

Of all the characters in the merry-prankster rolling revue known as Willie Nelson and Family, no one—not even Willie—casts a shadow like Paul, Willie’s shadow for life. He first drummed for Willie on the fly in 1955, on Willie’s radio show on KCNC in Fort Worth, and he drums for Willie today, assisted for the past thirty years by his younger brother Billy, who also plays percussion.

Inside the Family, Paul is the ultimate authority. He’s the Judge. It’s the same role he played back in Fort Worth in the 1950s and early 1960s when the Dixie Mafia ruled the underworld. If two hoodlums had a beef that they couldn’t take to the police, they’d go to Paul. No matter what he decided, his word was accepted as law, because Paul English had the reputation among characters as a man who was even-handed, judicious, and demanded respect.

“I was a good street hustler because I treated it as a business,” he explained.

He was born in Vernon, the North Texas hometown of hep jazz trombone pioneer Jack Teagarden, and moved with his family to the north side of Fort Worth, a rough-and-tumble part of a rough-and-tumble cow town. The Englishes were ardent Assembly of God church people, except for Paul’s older brother Oliver, who chose the life of a working guitarist, and Paul. (Younger brother Billy stayed with the church and played in evangelist Kenneth Copeland’s band until he permanently joined Willie’s band in 1984, and promptly fell off the wagon.) An accomplished boxer who competed in the Golden Gloves, Paul left the straight life behind when as a teenager he started hanging out in Hell’s Half Acre, the notorious honky-tonk strip located at the south end of downtown along Commerce and Calhoun Streets. “It was a whole new world,” he said.

After fighting and beating a gang of toughs who tried to jump him, Paul joined the Peroxide Boys, known for their chemically treated hair and their penchant for petty theft and jimmying pinball machines with BBs and wire for cash payouts. Running with characters named Cowboy and Lunkhead, he graduated to breaking and entering and general delinquency. The cops knew him by name. He claims to have been arrested over one hundred times. “Three busts in one day—staying up late until three o’clock in the morning, got out at seven, went back at noon, got out, they didn’t have any charges, they just put me in, then back in at nine again. We were penny-ante then.”

The desire to live the hoodlum life was understandable. Fort Worth was a wild, wide-open place with a colorful underworld that earned the city its reputation as a Little Chicago. Fort Worth’s gangsters were so lowdown, the real Mafia could never gain a foothold. Its Thunder Road, the Jacksboro Highway, was a strip of motels, bars, restaurants, and nightclubs that also functioned as illegal gambling casinos, whorehouses, and gutbuckets. (Speaker of the U.S. House of Representatives Sam Rayburn and local civic leaders preferred the gambling and drinking action at Pappy Kirkwood’s 2222 Club.)

Paul had plenty of role models—characters such as Tincy Eggleston, Cecil Green, future Las Vegas casino czar and Dallas “boss gambler” Benny Binion, who ran a Fort Worth vending company, and Binion’s nemesis, Herbert “The Cat” Noble, so named for surviving nine attempts on his life, only to get blown to pieces opening his mailbox. “They were all knocked off around me,” Paul once told a reporter. “There were as many as five blown up in a weekend.”

The characters maintained a moral code. “Fort Worth gangsters had families, everybody kind of worked together, they all knew each other’s family, they all needed one another, and of course the police over here were a little softer,” explained Richard Davis, a card dealer at Pappy Kirkwood’s. “There was more honor among thieves in Fort Worth. When those people started getting blowed up and killed, they deserved it. No one was killed without permission and it was usually for things like beating up on prostitutes or getting out of line with the law.”

Those characters inspired Paul to briefly experiment with explosives as a form of payback, on behalf of the Peroxide Boys, “but I wasn’t very good at dynamite,” he allowed. “We tried to throw dynamite into a bar for somebody else. It blew up here, and blew up over there, but only put a little hole in the roof. Didn’t do any damage. But I think they got the message.”

To this day, he remains proud of being featured in the Fort Worth Press tabloid’s Ten Most Unwanted criminal list five years running, and being a fixture on the daily Perp Walk police staged for newspaper reporters. “We’d go make that circle and [the cops] would go, ‘These people are known to have done time in the number two tank.’ The number two tank was where the drunks are.”

Still, Paul English managed to avoid doing time, with one notable exception. “I did go to jail for nine months,” he admitted. “For something I didn’t do. That’s really the truth. I swear to God I didn’t do it. I was seventeen years old. There were these two brothers. We had to go by and pick up the older brother, and we drove around. He said so-and-so went out of town. ‘Let’s go raid their refrigerator.’ That’s what they did. Me and this other guy from Fort Worth, he was one of the gang, we said, we don’t want to go in there. We waddn’t gonna have no part of it.” But Paul and his buddy were arrested for burglary anyway, when the getaway car he was driving broke down.

“My dad, bless his heart, he got a twenty-five-dollar lawyer, he got us out on a misdemeanor.”

During that nine-month stretch, which included field labor in the county pea patch, English learned two valuable lessons: “I met a good thief who told me, If you’re going to be a thief, be nothing but a thief and plan to spend two-thirds of your life in prison. He said the best route to take was in the rackets, because there was no jail sentence, there’s more money, and you’re dealing with a higher class of people.”

He also learned how to play chess.

The stretch in jail compelled Paul to go straight for a couple years, working alongside his cousin tooling decorative leather saddles (his leatherwork adorns the cover of the Willie Nelson album Tougher Than Leather). One day in 1955, he tagged along with his older brother Oliver, who had a noonday gig playing steel guitar on the Western Express radio show on KCNC. The regular drummer on the thirty-minute program, Tommy Roznosky, didn’t show, so the program’s host, Willie Nelson, suggested Oliver’s little brother fill in. Paul had never drummed before, though he played trumpet at school.

Paul had been a big fan of the Western Express show and was surprised when he went to the studio and learned that the host was about his own age. “I thought he was an old man,” Paul said of Willie, whose radio persona was the “ol’ cotton-picking, snuff-dipping, tobacco-chewing, stump-jumping, gravy-pot sopping, coffee pot dodging, dumpling-eating, frog-giggin’ hillbilly from Hill County, Texas.”

Paul was up for the challenge.

“They had a snare drum, and my older brother said, ‘Just start going one and two and three and four.’ That’s all I could do,” Paul said. “Someone gave me a bass Salvation Army drum, and I hooked a pedal up to it and sat on a Coke box and managed to hook some bongo drums to the bass drum,” he recalled. “They told me to just keep patting my foot. They kind of counted out every song for me, just one, two, three, and four.”

Paul sat in on the radio show for three weeks. Willie was sufficiently impressed that when he scored a gig at a beer joint called Major’s Place, he asked Oliver to bring his little brother along again, so he could get paid to play. Eight bucks a night. The gig lasted six weeks before Major’s shut its doors for good. “The money wasn’t that great, but I loved playing, and I got to play in front of the girls,” Paul said. “The girls loved musicians.” He was hooked.

Oliver and Paul ran a car lot at 2222 North Main and they sold Willie a 1946 Buick convertible, one owner, black with red leather upholstery. “I paid $165 and the $22 tax and sold it to Willie for $175 on time for $25 down,” Paul said. “I lost money on the deal.” But it didn’t seem to bother Paul, who had become smitten with the musician’s life, picking up gigs wherever he could. He worked some of the rougher joints in town, such as the County Dump, which happened to be adjacent to the county dump on Fort Worth’s east side. “They couldn’t get anyone to play there because it was so rough,” Paul said. “My brother and I picked up a trumpet player who didn’t want to go. I told him it wasn’t rough anymore—we carry guns. That night, there were two fights and one knifing.” The trumpet player didn’t come back.

Paul’s cousin Arvel Walden sometimes worked with Paul as a two-piece at a joint that hired them to make enough noise to cover up the craps game going on in the back of the club. On one night that Arvel took off, his replacement was stabbed.

Meanwhile, in 1960, Willie arrived in Nashville, where he flourished as a songwriter, a sideman in Ray Price’s Cherokee Cowboys, and as a solo recording artist. Paul returned to the rackets after the leather trade dried up (“They didn’t know what good leather tooling was”), finding his sweet spot as a pimp fronting prostitutes.

“I started having girls at twenty-two,” he said. “I knew this girl, asked her if she’d like to work, went from there. I was a good pimp,” he recalled in a soft voice tinged with fondness. “I never did beat a girl. We called men who did that wimps. How you gonna beat them up to make them stay?”

English preached expediency to his girls. “I’d tell them to light a cigarette, put it in the ashtray, let it burn. When it’s burned down, it’s time to go. It don’t take very long.”

He started running girls out of the Western Hills Inn resort in suburban Euless, even though the house took a higher cut. “The bellman took forty percent and there was a ten percent taxi tax,” he said, explaining that it was worth the reduced percentage. “It was the people coming through there—cowboys, movie stars,” Paul said. “We had Desi Arnaz, he was a good trick. He always wanted a party. They’d give girls five hundred dollars walking in. They’d do the trade after that. They’d get more money for the other stuff.”

He expanded his enterprise to Dallas, Waco, then to Houston, Texas’s biggest city, and was pulling down $3,000 a week, enough to purchase several rent houses. His so-called career also allowed Paul to continue playing music as a hobby, frequently sitting in with Ray Cheney’s house band at the Stagecoach Inn on Fort Worth’s east side, with his cousin Arvel, and with Good Time Charlie Taylor & His Famous Rock and Roll Cowboys, whose cardboard posters featured the handsome floating head of Paul, replete with Sal Mineo curl and pencil-thin moustache, as “The Bip Bop Drummer.”

Paul kept close track of Willie’s career. In 1962, Liberty Records released . . . And Then I Wrote, Willie’s debut album, singing his own compositions, some of which had been hits for other artists. Paul went to a radio station with the new vinyl album and had the record transferred to a tape cartridge so he could listen to it on his newfangled Autostereo Stereo-Pak four-track stereo tape cartridge player as he drove to check on his interests in Houston and in Waco.

Paul and Willie stayed in touch. Paul bought Willie a guitar and loaned him money whenever he was short of cash. After Paul relocated to Houston, he would provide a place for Willie to stay whenever he was playing in the area, sometimes with a working girl who lived downstairs: “I let her go to bed with him. Her old man was in the penitentiary.”

During one Houston stopover in 1966, Willie asked Paul if he had Tommy Roznosky’s telephone number. He needed a new drummer, because Johnny Bush was ready to step up and be a full-time front-man and singer. “You don’t want to call him,” Paul insisted. “Let me play drums with you.”

It was a stretch. Paul was hardly a polished pro, but country drumming required a steady beat and not much more. But would Paul be willing to take a cut in salary? Willie asked. Paul didn’t hesitate. He had it made as a character, and had saved enough money that he could afford to join Willie’s band. Paul saw it as a calling; he really loved and cared for his friend. Willie was a genuine Nashville recording star, but he worked in a very rough business. He needed a character like Paul to protect him.

“The club business was rough, so you went in with a you-motherfucker-you-better-pay-me attitude from the start,” Willie told me for Willie Nelson: An Epic Life. “When I was with Ray Price, he’d always say, ‘You guys hurry up, let’s go. Let’s not give the sumbitch an excuse not to pay us.’ Every day he would say that. And he was right. They were just looking for an excuse not to pay us.”

One night in San Diego shortly after Paul had signed on as one of Willie Nelson’s Record Men, Johnny Bush, the drummer-turned-singer who did the band’s accounting on the road, started throwing up blood after a day trip to Tijuana. “I had to take him into the hospital and go do the books that night,” Paul said. “When he came back, Johnny didn’t want any part of it. He said, ‘Take it.’” Doing the books came naturally to the son of an accountant.

With Paul on board, the pay became more dependable, even though there were inevitable missteps, like the only time Paul got stiffed settling up after a gig in Florida. Paul and the owner were niggling over the $900 performance fee; the club wanted to pay only $750. “If Willie would’ve kept out of it, we would’ve got paid something,” Paul said. But Willie managed to make his way to the office during the haggling. When he blurted, “All or nothing,” that left Paul in a tough spot. “I was trying to get more when Willie came in. So I just got mad at the [club owner] and ran out to the bus to get my pistol. But when I tried to get back inside, they had shut the steel doors in front of the club. I tried to kick the doors open but couldn’t. They had cops working for them anyway.”

“But you know what? Two months later, that guy got blown up,” Paul added. “I didn’t have anything to do with it.”

If a club owner didn’t understand Paul’s method of gentle persuasion, he would make plain his intentions. He once commandeered a forklift outside a club in New Mexico and used it to raise the recalcitrant club owner’s Thunderbird, taking the car keys with him and leaving a note that read, “Come see me.” The contracted performance fee was paid in full. Word began to travel about Willie’s bagman.

“I wasn’t a really nice person when it came to collecting,” Paul said. “You see, I have a good reputation. A character means exactly what he says. A character has got to have a lot of character. I never drank, didn’t smoke until I was thirty-four, have never had a needle stuck in my arm outside a hospital. All that wasn’t done where I came from. A character has to treat everybody right. When you call a friend a friend, you have to treat him as a friend. It’s respect. Being a character means respect.”

It wasn’t just getting respect from the people who ran the beer joints that Willie was working. Patrons had to be kept in line too. On an off-night in Phoenix, Willie Nelson and His Record Men were hanging in a bar when Doyle Nelson, Willie’s stepbrother, who was driving the band bus, came to Paul with a problem. Two guys he’d been playing pool with lost their bets but wouldn’t pay up. Paul walked into the poolroom with Doyle and confronted the two men.

It was just for a quarter, one man protested.

“Pay him the quarter,” Paul instructed. “Anybody who won’t pay on a bet is a rotten motherfucker.” These were clearly not men of honor. Fists flew. Paul was pounding one miscreant when the other came up from behind and pulled him off by wrapping a pool cue around his neck. Paul reached into his pocket and swung his right arm up, placing the barrel of his .22 pistol in the assailant’s right nostril, ready to fire. Just then, Willie conveniently walked into the room, declaring, “Paul will whip any one of you guys, and I’ll take the other.” The fight was already over.

English’s reputation grew to the point that verbal intimidation was often all he needed. He had invested in Johnny Bush’s career, but wasn’t happy with how Bush’s label, Stop Records, was promoting their act. “I’m from the old school where if you make a contract with somebody, you better honor it,” Paul said. “If you don’t, there are consequences.” Pete Drake, the pedal steel session player who co-owned the record company, had not lived up to the contract. So English paid him a visit.

“I don’t care if I made a quarter or lost a quarter, I want to settle,” he told him. “I’ll take that record and go across the street.”

“You cain’t do that,” Drake insisted.

“I can do that,” asserted Paul.

Then he added, “I’ll tell you what I can do. I can take your ass out in the woods and tie you up with barbed wire and leave you there in the middle of nowhere. If you can escape on your own, fine. Otherwise, I’ll come back every day so you can thank me because I let you live one more day.”

Drake bought out English, satisfying all parties.

Paul became Willie’s protector. “Willie was a bad drunk. When he got really liquored up, he’d want to drive,” Paul said. “I’d have to take the keys from him. He didn’t know what he was doing, he was so drunk on whiskey and pills.” Paul got Willie into chess and into golf and paid Willie’s utility bills, even though he was owed $5,000 in back pay. Over the course of several years, Paul sold several rent houses to keep the enterprise going, because Willie wanted to play, and because Paul believed in Willie. “Back then, we were making what we could make,” Paul said. But he sure wasn’t in it for the $100 weekly salary.

At Willie’s urging, Paul purchased a black satin cape with red satin lining at Sy Devore’s in Hollywood and started wearing it onstage, cultivating his image as the Devil, “the prettiest angel in heaven,” as Paul liked to say. Shortly after he bought it, he was wearing the full-length cape on the elevator of the Holiday Inn in Hollywood where the band was staying, along with a black shirt, black pants, red patent leather boots, and his sculpted goatee, when the elevator door opened up.

Paul stepped off the elevator just as Little Richard was entering, wearing his own cape. “But Little Richard’s cape only came to his waist,” said harmonica man Mickey Raphael. “Paul walked out, head held high. Little Richard walked in, and did a double take.”

When Paul added some dry ice to create a smoke effect around his drum kit for a gig at Panther Hall in Fort Worth, he discovered the cape getup was a chick magnet. “When I got offstage, there were fifteen girls waitin’ for me, wanting my autograph,” he smiled.

For his part, Willie helped Paul tamp down his anger. “I was really hostile,” Paul said. “If somebody was to say something wrong to me, they would have a fight. I finally learned from Willie to turn around and say, ‘Thank you very much.’ And they’d stand there with a guilty look on their faces and wonder, ‘What did I just say?’”

“Characters believe that violence breeds violence, but Willie is given to a lot of tolerance. I’m sure I’ve changed his attitude towards a lot of things and he’s changed mine.”

Willie’s third wife, Connie, was introduced to the other side of country music stardom through Paul. “All I’d seen of guns was on TV,” she said. “I knew they had them for protection on the road, I knew stories about Paul. That was just family. And protection. He was protecting Willie and the family and anyone in the house.”

“With Paul,” she said, “Willie’s always safe on the road. We named Paula after him.”

When Willie Nelson’s home at Ridgetop outside of Nashville burned down just before Christmas in 1970, the band and their families relocated to a foreclosed dude ranch in Bandera, Texas, near San Antonio, and eventually found their way to Austin, traveling in an armor-plated Open Road camper that was filled with enough arms for a small invading force, and usually occupied by several kids rolling joints.

As Willie’s renown grew, the money got decent and getting paid became a lot easier. At the first Willie Nelson Fourth of July picnics, beginning in 1973, instead of having to shake down the money-man to get paid, Paul was the money-man, walking around with $100 bills hanging out of his pockets, a bone-handled skinning knife conspicuously on his hip, and a pistol stuffed in a sock, practically daring anyone to fuck with him. He also provided the extra service of draining the tarp covering the stage after heavy rains by shooting a hole in the fabric with his pistol so the show could go on.

By this time, Paul had already endured the biggest takedown in his life when his wife Carlene committed suicide in Austin in 1972. Paul dropped seventy pounds and lost so much interest in drumming that a second drummer, Rex Ludwick, was added to the rapidly expanding Family band, along with a second bassist, Chris Etheridge, to complement Bee Spears. Willie paid tribute with one of the saddest songs he’d ever written, “I Can’t Believe You’re Gone.”

Willie’s longtime pedal steel player Jimmy Day, whose history with Willie extended back to his first demo sessions in Nashville in 1960, offered a wisecrack instead of sympathy, and paid for it when he remarked loudly one day at Willie’s house, “Shit, if I had to be around you all the time, I would’ve killed myself too.”

Without saying anything, Paul pulled his .22 from his boot, aimed toward Day, and pulled the trigger.

“I didn’t shoot at him,” Paul said after the fact. “I shot way over to the left about twenty-five yards away from him, down the hill. When I left, I said, ‘I’m going to shoot him the next time. Jimmy’s going to pay for it.’ About that time, Willie’s youngest daughter, Amy, said, ‘Don’t kill him, don’t kill him.’ I couldn’t do that, so I hit him on the head, threw him downstairs, I went down, picked him up and put him in the car. I let him know the shot was wide and that if he came on my property, I could kill him.” Point made. Willie fired Jimmy Day.

Jimmy Day never liked Paul. He didn’t respect him as a musician and resented his close relationship with Willie. Jimmy was a picker through and through, a genuine pedal steel maestro. What Day did not fully appreciate was how Willie was creating his own distinct sound playing off of Paul’s light touch, Bee Spears’s mystical bass lines that followed a rhythm pattern only he and Willie could decipher, and Mickey Raphael’s distinctive harmonica wail.

Day would reappear at Pedernales Studios, Willie’s personal recording studio west of Austin, in 1981 to play on a session with Willie and Roger Miller, reuniting the three former members of Ray Price’s Cherokee Cowboys. By chance, Paul happened to drop by the studio. When he spied Day, he made a beeline toward him, saying, “Now, I’m going to tell you something. I told you not to ever come around me.” He landed three rapid-fire punches that sent Day tumbling with his pedal steel guitar landing on top of him, before Willie jumped on Paul’s back.

“Why did you have to do that?” Willie protested, mildly.

“I had a feeling there had been a security lapse,” Paul mumbled. Nothing further was said. It would be another ten years before Paul allowed Day to return to Willie World.

With a string of successful albums, starting with Red Headed Stranger in 1975 and running through Wanted: The Outlaws and Stardust in 1978, Willie blew up into a superstar, even though the organization retained some of its old-school ways. Paul refused to let the band take the stage when they were playing a private party for HBO until the $70,000 check he was handed was turned into cash.

When Ray Benson, leader of Asleep at the Wheel, had to get in the face of an El Paso promoter for turning up the lights before their set opening for Willie was finished, Paul saw what was happening and pulled Ray aside.

“You having problems?”

“Yeah, this fuckin’ promoter is jacking with us.”

“Here, take this,” Paul said, offering Ray his .22 pistol.

When Jerry Lee Lewis and two associates appeared on stage in the middle of a show in Memphis, and the Killer took it upon himself to lift up a corner of the piano being played by Bobbie Nelson, Willie’s older sister, Paul pulled out his pistol and placed it in the floor tom of his drum kit while he played. “I let him see my gun,” he said, “And he didn’t get on Bobbie’s piano.”

Paul English feared no one, not even the biggest concert promoter in rock, the acid-tongued Bill Graham, of Fillmore fame. Mark Rothbaum, Willie Nelson’s business manager, got crosswise with Graham at an August 1980 show in Sacramento.

“We were playing Hughes Stadium, an open-ended football stadium,” Rothbaum recounted. “There are a carnival and Ferris wheel in the open end of the stadium that Bill Graham had rented. The bill was Waylon, Haggard, Emmylou, and Willie. Willie went on last, about four in the afternoon. Bill was being Bill, taking me to task about the sound. We’d hired Showco to do the sound for us and it was bouncing around the stadium. I’m behind the stage in an open area, watching Willie play and Bill comes up and starts pointing at me.

“‘Sound’s no good. The sound is shit. Why did you bring this piece of junk?’”

“That’s the way Bill was,” Rothbaum said. “I would take more from him than anyone. He earned it.”

“As we’re talking, I see Paul jump off the bandstand and see Paul running towards us. Graham has his back to him. Paul knocks him down, pulls out a gun and aims it at him, telling him in that stuffy, nasal whine, ‘You don’t disrespect him. You don’t point at him.’

“I said, ‘Paul . . . put . . . the gun . . . down.’”

English put down his pistol, put his arm around Graham and walked him back behind the stage, talking to him the whole time, before sitting him in a folding chair. “Don’t talk to my people that way,” Paul advised Graham. “We’re working here. You might could fire us, but I could fire you from the human race.” English summoned over one of the Hell’s Angels who were doing security for the show and told him to sit with Graham until Paul was finished playing.

“Paul felt the responsibility to defend me,” Rothbaum reflected. The paternal head of the Family felt that way about everyone. “I’ve never had that kind of protection from anyone,” marveled Rothbaum, who was something of a pitbull himself. “Push did come to shove, and he shoved.”

One of the first shows Rothbaum attended after Willie made him manager (after Rothbaum took the fall for Waylon on a cocaine rap) was in Nebraska. “Two FBI agents showed up and said they came to talk to Paul,” Mark related. “No problem. I took them backstage, got them some coffee and sweet rolls, and called over Paul saying, ‘Paul, these two agents want to talk to you.’”

Paul glared at the agents. “I’d like to fucking talk to you,” he hissed, “but I cain’t, so you cain’t talk to me.”

Rothbaum couldn’t believe what he was hearing, so he solicitously said to the agents, “Bear claw? Danish?”

Rothbaum was thunderstruck. “Keith Moon, David Lee Roth, Led Zeppelin—those guys are pussies,” he said. “Paul is the devil. He’s a badass.”

“I’ve faced some tough people,” he said. “Forget Miles, forget Waylon, or Willie. I have never faced anyone like Paul. The gun is his way of communicating. He may not be the most articulate speaker, but if he wants to make a point, he can do it. A thousand times I’ve seen him intimidate. Together, we made a pretty good presentation on behalf of Willie Nelson.”

English similarly managed to avoid testifying in front of a grand jury in Dallas investigating a drug smuggling ring, involving people uncomfortably close to Willie. “I didn’t have to testify. Willie didn’t have to testify. Willie got a lawyer to go up there. I went up there on my own. I just refused to answer anything. They asked me if I knew a certain guy. I refused to answer that.”

He’s dodged more than a few figurative and literal bullets, although one leg has fragments from a long-ago shooting and scars decorate his fists. “I’ve had a few fights,” he said somewhat wearily, holding up his left hand. “I got this one October 29 in Houston in ’79. I was playing and a guy who had a full beer threw it at Mickey. He missed him by just this much. I had security bring him over in the back. He used to be a boxer, he said to me. Well, I used to be a boxer too, I told him. Come on over here. He was looking for my right hand. I caught him with my left. I hit him more than once.”

But all that is in the past. “It’s different now,” he said. “They send half the guarantee as a deposit. It’s not near enough fun.”

Success, fame, and age have sanded English’s rough edges considerably.

He married Janie and raised a second family. When the Internal Revenue Service presented Willie Nelson with a $32-million bill for unpaid taxes in 1988—“I told him and told him,” Paul said of Willie’s tax troubles—the band spent an extended stretch off the road while lawyers and accountants resolved Willie’s tax problems. That translated into the Family’s IRS Kids—the birth of several children, including Annie and Willie’s two sons, Micah and Lucas; a pair of daughters born to Suzanne and Buddy Prewitt, the lighting director known as Budrock; and a new brood for the Englishes.

Robert Paul Jr. learned early on that his namesake was not like other daddies. “When I was about ten, me and my cousin Joey were playing hide and go seek, and for some reason opened up the piano, and there were two big sawed-off shotguns and several assault rifles. The piano was literally a weapons cache.”

Paul Jr.’s favorite piece remains discreetly out of view at home. “It’s a big .45 that looks like one of those guns they confiscate from Mexican drug lords,” he said. “It’s silver with a gold trigger and engraved with filigree depicting my dad having an orgy with several women down the left side of the barrel; on the other side, he’s eating some girl’s pussy out. If I’m pointing it at you, right over the barrel, it says, ‘Welcome to Hell.’”

Over the years Paul Jr. has come to realize the importance of firearms in burnishing his father’s reputation. “There’s an old picture of my dad and Willie, sitting in a chair, that’s been hanging in my house for years. Two years ago I noticed two guns my dad was carrying.”

The good news is, Paul’s reputation does most of the talking these days. “It’s nice when you don’t have to be shooting people,” said his son, who would like to honor his father by making a movie about him. “Without Paul, Willie’s story is half as interesting. The music’s still gorgeous but there’s no shoot-out at Lana’s house. All these stories are part of the legend and serve to define outlaw as outlaw, legitimately outside the law. He was the real deal. You knew somebody onstage had a gun, and it was probably the guy on drums.”

And there remains the song “Me and Paul,” the story of two vagabond musicians who almost get busted in Laredo for having marijuana, who earn the scrutiny of airport security, and who get so out of sorts they miss their featured appearance on a country music package show in Buffalo. You hear it sung at almost every Willie Nelson show, and when Willie kicks off the tune, Paul visibly straightens up and smiles as the spotlight turns to him, picking up the shuffling rhythm on his snare drum.

Easier times have not diminished his stature. “I still go to Paul for advice,” said Mickey Raphael, the sixty-two-year-old “kid” in the band. “I learned a lot about character, honesty, no bullshit, fairness. Even if [Paul’s decision] didn’t come out in my favor, I knew it was the word. You had to have a leader.”

“I never would have gotten hired if it wasn’t for Paul. Paul was the one I’d see when I got paid, the one who took care of you. It was almost like the Stockholm Syndrome. Here I am riding around on a bus with these lunatics.”

“He’s like a sleeping dog,” Mark Rothbaum said of Paul. “He’s okay if he’s asleep. But if he’s not asleep, he’ll cut you down. He’s mean. He’s got a mean streak in him. The guy don’t scare. Paul and I have not had a bad word between us. We’re after the same thing—for Willie to be respected. Together, we mean business.”

New boy Kevin Smith, the bassist who replaced the late Bee Spears in 2012, said he didn’t know his status with the band until Paul informed him he was added to the payroll. Paul’s words carried weight.

And the star of the show, Willie Nelson, simply says: “He’s my best friend.”

So the gun-toting eighty-two-year-old character who does the books every day on computerized spreadsheets on his touring bus, plays chess with his boss long-distance via iPad, and resolves problems among the crew or with promoters before he escorts Miss Bobbie Nelson to the stage and takes his place on the drummer’s chair, keeping time and watching Willie’s back, sees no reason to stop.

“It’s a good life,” he said, cracking the slightest grin. “I’m playing with my best friend. Why should I quit?”

Enjoy this story? Subscribe to the Oxford American.