Chosen History

By Mychal Denzel Smith

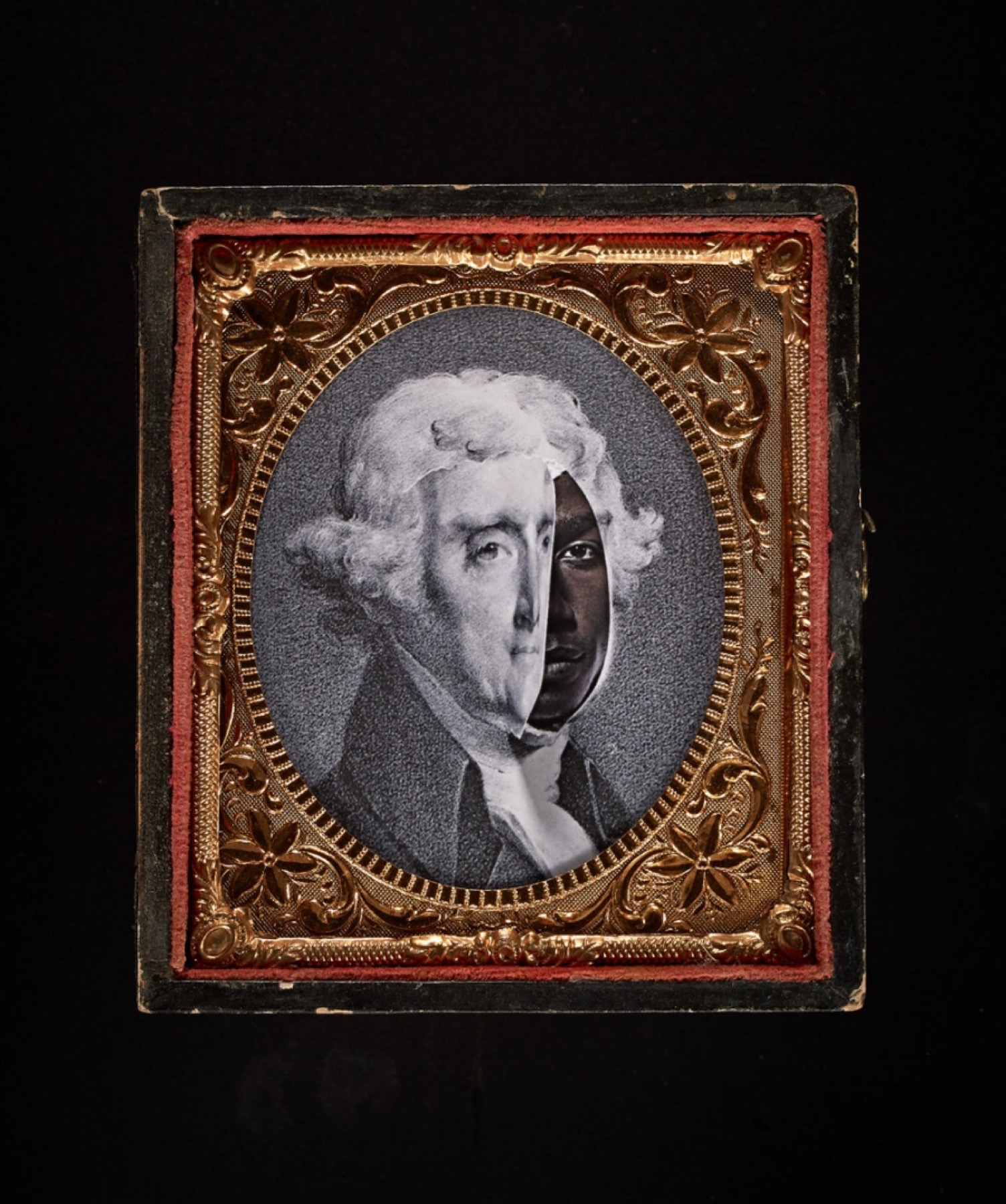

“Jefferson,” by Maxine Helfman, from the series Forefathers

Thomas Jefferson, Pharrell, and more notes on the state of Virginia

I wasn’t born in Virginia, and for a long time I was reluctant to claim the state. I was born in 1986 in Washington, D.C., where both of my parents were born and raised, their families having made it there as part of the mid-twentieth-century migration of black folks out of the South toward what they hoped would be more opportunity, more freedom. My father was in the Navy, and we moved to naval housing in Norfolk (which, if you’re from Virginia, is pronounced “Nor-fuck”) for a spell when I was a toddler before a three-year stint in Naples, Italy. Beginning in 1993 my father was stationed in Virginia Beach, where we settled and where I’d spend my formative years. My cousins from the “big” city of D.C. made fun of me for being from the country and I felt more than a little embarrassed in their presence.

Where we lived was far from country—not like the part of Virginia where my granny is from. Max Meadows is country. There still aren’t more than three or four stoplights in that town. Granny has demonstrated on more than one occasion the way they used to kill chickens with their bare hands, grabbing the live bird by the neck and twisting until it snapped. That’s country.

I’ve never killed a chicken with my hands, or with anything for that matter. I grew up on the corner of a cul-de-sac in a planned neighborhood made up of cookie-cutter houses with driveways, backyards, and fences. It was the suburbs, without any real urban center to sit adjacent to. Our accents didn’t carry much country flavor, unlike the thicker, slower ones you’d find toward the western part of the state. What was left of the Tidewater accent had been thinned out by the influence of people who had come from all over and settled there as members of the armed forces.

Still, I was guilty by association. Virginia was the South, and the South meant country, which meant slower, dumber, backwards, uncultured. In D.C., radio stations played the latest hit songs weeks and months before ours. If I decided to try out what I thought was new slang on my cousins, they would laugh because they had moved on to something else. Our mall stocked Tommy Hilfiger when everyone had moved on to FUBU, then finally got FUBU once the trend shifted to Rocawear.

My cousins grew up sophisticated, in my estimation. Their city had pro sports teams to root for and a public transportation system that allowed them to be independent at a young age. They had major tourist attractions in the way of internationally recognized museums and historic monuments. Where I lived, we had Mt. Trashmore, which is more or less precisely what it sounds like: a former landfill that was turned into a park (it was fun to run up the hill and roll back down). Virginia Beach was one of the few things that my cousins genuinely enjoyed about my home, though the water is the ugliest shade of Atlantic Ocean brown.

Everyone from everywhere had heard of D.C., but Virginia Beach required explanation. As a place, Virginia itself was met with disinterest. I only ever heard non-Virginians talk about us to complain about our terrible drivers (which, true) or mock our terrible tourism slogan (“Virginia Is For Lovers”). We were only in the national news when a hurricane headed our way. We had a black governor once, the first black governor ever elected by any state, but he was elected in 1989, before I even knew what a governor was.

There were no cultural works of great significance that used Virginia as a setting or a character. Artists did not come to our state for inspiration. No one was trying to capture our essence as a statement on the human condition.

If Virginia didn’t matter outside of Virginia, it did, however, matter to the Virginia Beach City Public Schools. In the fourth grade, history class centered on Virginia history, and toward the end of the year my class took a field trip to Jamestown. In fifth grade, we went to Colonial Williamsburg. I learned that four of the United States’ first five presidents were from Virginia (though I’ll admit that I had to look that up before setting it down here). Even as a child I didn’t find this fact worth remembering, at least not as some decontextualized data point. But I realize now what Virginia public school students were expected to internalize: that Virginia is mighty, powerful, and important, a place crucial to the development of the United States of America, the most mighty, powerful, and important nation on earth.

And it’s true—many important historical events took place in Virginia, not least of which was the founding of the first permanent English colony, in Jamestown, circa 1607. Even if schoolchildren elsewhere didn’t have to commit our presidential tally to memory, they couldn’t learn American history without learning this, and perhaps not without also learning that the first Africans brought to our country to be enslaved came through the same area in 1619 (though many historians say that they arrived in the Americas at least a century earlier). There was also Bacon’s Rebellion in 1676, the first popular uprising in the American colonies, which served as precursor to the Revolutionary War. It was a multiracial effort on the part of indentured Europeans and enslaved Africans, fighting against the tyranny of the ruling class, which, along with other factors, eventually led to the establishment of the Virginia Slave Codes in 1705, an attempt to ensure these two groups would never again join forces. It also had its roots in targeting and scapegoating Native Americans for issues of unfair trading practices and exorbitant taxation. By the mid-1700s, the Susquehannock people were nearly entirely killed off.

There is more. Later, in Richmond, Patrick Henry spoke his famous words in the lead up to the Revolutionary War: “Give me liberty, or give me death.” (Today, he is honored by having a mall named after him in Newport News.) The last major battle of the Revolutionary War took place in Yorktown, where General Charles Cornwallis surrendered in 1781. The Virginia Plan, credited to James Madison, helped to determine the structure of our national government, giving us the two houses of Congress, as well as the idea of determining representation in the House based on population (Virginia was the most populous state at the time). This led to the three-fifths clause, which held that enslaved people were to be counted as three-fifths of a person for purposes of determining population size.

So yes: Virginia liked to brag about its history, which made sense. Virginia was a major player in the founding of this nation. But it’s telling which aspects Virginia chose to brag about to schoolchildren.

How you tell a story, and what parts you tell, matters.

Thomas Jefferson is Virginia’s most celebrated son, born and raised in Shadwell, toward the northwest part of the then-colony. He, of course, drafted the Declaration of Independence, served as the first secretary of state of the newly formed United States of America, then as its vice president, then was sworn into office as president in 1801. In 2000, the year I started high school, a group of historians assembled by the Thomas Jefferson Foundation reported that a DNA study showed a high probability that Thomas Jefferson was the father of Eston Hemings. This confirmed the rumors that had persisted since Jefferson was still alive: that our third president fathered a child with one of his slaves, Sally Hemings. The foundation’s findings would become the final word on the matter, after the historian Annette Gordon-Reed reignited the conversation with her 1997 book Thomas Jefferson and Sally Hemings: An American Controversy. Though Jefferson’s defenders had tried over the years to suggest it may have been his brother, a cousin, or even one of his sons who fathered Eston Hemings, the DNA evidence was fairly definitive in pointing to the Founding Father. Americans had to face the fact: Thomas Jefferson was a rapist who fathered a black child. There can be no ambiguity about this, as Sally Hemings was never in a position to consent to sex with Thomas Jefferson. He owned her, and this is not euphemism; Jefferson held the legal rights to Sally Hemings’s body, labor, and life since she was an infant. Consent cannot occur under such conditions—only coercion. Hemings was about sixteen years old the first time she gave birth.

Jefferson was not the only slave owner to father children with his property, though the paternity debate surrounding him was so contentious because of what he means to the American identity. He was the intellectual father of this country, its chief moral philosopher. “All men are created equal” is a credo the U.S. prides itself on, albeit one it has never lived out. The man who wrote those words enslaved more than six hundred people throughout his life. Still, he was able to establish a reputation for being anti-slavery, as he made many public proclamations about the abhorrent nature of the institution. His original draft of the Declaration includes a passage condemning the slave trade and King George III for his role in its maintenance: “He has waged cruel war against human nature itself, violating its most sacred rights of life and liberty in the persons of a distant people who never offended him, captivating and carrying them into slavery in another hemisphere, or to incur miserable death in their transportation hither.” And yet, for all of Jefferson’s righteous indignation, he freed very few of the people he himself enslaved.

My history teachers in high school didn’t talk much about Thomas Jefferson’s rape of Sally Hemings, though they talked endlessly about the Louisiana Purchase. Oddly, as omnipresent as Jefferson was, I never went on a field trip to Monticello. To this day I have never been. Frankly, I don’t give a fuck about Thomas Jefferson, and he wasn’t much on my mind when the DNA evidence was released. That was the summer of “Shake Ya Ass.” It was the summer we all learned about Pharrell.

Now, when strangers ask me where I’m from, I say, “Virginia Beach. We gave the world Pharrell. You’re welcome.” Pharrell was the black cosmopolitan force that proved my home wasn’t country. He was a living rebuke of what Thomas Jefferson wrote in Notes on the State of Virginia, his only book, in which he says you would “never . . . find that a black had uttered a thought above the level of plain narration; never see even an elementary trait of painting or sculpture.”

His individual stardom is more than established now, but Pharrell started as one-half of the production duo the Neptunes, alongside fellow Virginia Beach native Chad Hugo. They were discovered by Teddy Riley, the producer often credited with the creation of New Jack Swing, that distinctly late-1980s/early-’90s mélange of black musical forms—funk, r&b, hip-hop, soul, jazz—and best summed up by Bell Biv DeVoe, one of the sub-genre’s most successful artists: “Our music is mentally hip-hop, smoothed out on the r&b tip, with a pop feel appeal to it.” Riley set up his studio near Princess Anne High School, where Pharrell attended, and found him, alongside Hugo, at a high school talent showcase. Pharrell did some production work and writing on one of Riley’s big hits, Wreckx-N-Effect’s 1992 party anthem “Rump Shaker.” The duo of Pharrell and Chad, under the Neptunes moniker, spent a few years apprenticing with Riley before they broke out on their own to establish their sound: sparse percussion and synthesizer riffs that gave everything an electronic feel.

It was the summer of 2000 that cemented their status as go-to producers. Mystikal was striking out on his own, away from the No Limit Records machine Master P had built out of New Orleans, and had turned to the Neptunes for a few beats for his fourth solo album. He initially didn’t want to release “Shake Ya Ass” as the lead single, perhaps because his actual rapping is a secondary element to the song. But a hit is a hit, and this would become the biggest hit of Mystikal’s career. Everything about it is infectious, even if you’re listening to the clean version, “Shake It Fast.” The song thrived in an increasingly ass-focused cultural landscape that had recently fallen for J.Lo’s curves, Sisqo’s “Thong Song,” and Juvenile’s “Back that Azz Up.” “Shake Ya Ass” hit a slightly darker, more sultry, almost forbidden note.

The song, and accompanying video, feel ready-made for sweaty midnight house parties with red lights and wall grinding. It also introduced the world to Pharrell’s strained and inviting falsetto. He could be heard on a few other Neptunes productions (and has a brief rap performance on the UK remix to SWV’s “Right Here”), but this was the first big hit where Pharrell was singing as an integral part of the song. “Attention all y’all playas and pimps, right now in the place to be,” he starts, almost sweetly, “I thought I told y’all niggas before, y’all niggas can’t fuck with me.” Hardly anything is more hip-hop than declaring your own superiority. “Now this ain’t for no small booties, no sir ’cause that won’t pass,” he continues before he drops his voice a few registers to say, “But if you feel you got the biggest one, then mama come shake ya ass.” Then Mystikal is back like a madman to direct the shaking, even as he warns, “Watch ya’self.”

The Neptunes made hits for Jay-Z and Ludacris, then Britney Spears and *NSYNC, moving seamlessly through the worlds of the hottest rappers and the biggest pop stars. As a duo, they became a sensation, the most sought-after hitmakers of the time, and Pharrell became a legitimate star in his own right because his voice was fundamental to the Neptunes’ sound. It didn’t hurt that he was handsome and not at all camera shy, unlike his camera-phobic production partner Chad.

No matter the setting, Pharrell possessed a rare ability to be himself. I envied this: He fit in everywhere at a time when I felt I fit in nowhere. And he did it without blending in. He called himself a nerd, as if it were something to be proud of, whereas I balked the first time I was called a nerd, afraid of it marking me as other. Pharrell thoroughly embraced his otherness. He named his avant-garde alt-rock Neptunes-offshoot band N.E.R.D. He was an unabashed Trekkie who liked skateboarding. He was as influenced by David Bowie as he was by A Tribe Called Quest.

I have never believed that blackness itself has limits—and Pharrell didn’t impress me as the embodiment of a statement about how it was okay to be a different kind of black. What I didn’t realize was that you could be this kind of other and still hang out with Jay-Z. Pharrell could move among the men who looked like the boys I knew who seemed to have things figured out, and with such ease. As a teenager, I longed for acceptance from those boys, who were not unlike my D.C. cousins. I copied their outward appearance, hoping that could win them over, but I only got to the fringe. Yet I was fascinated by Pharrell, he who seemed to say “fuck it” while living out his nerdy truth and supplying the soundtrack for those men to tell their tales of survival and street politics, but also their sexual exhibitions and misogyny.

I learned that Pharrell was from Virginia on MTV, where “Shake Ya Ass” was in regular rotation. Interviewers rarely asked him about Virginia, or only mentioned it in passing before moving on to his high-profile connections, his successful career, his model wife, and his unique artistic perspective. They were never curious about the place where his vision came together. When I heard them say where he was from, it was all I cared about.

I don’t think Pharrell thought of himself or his music as being some sort of instructional guide for kids like me; he was just trying to produce a jam. And he did. But he was also making cultural statements about male desire and forms of acceptable behavior, whether he intended to or not. Accusations of misogyny were never directed at him the way they were toward his rapper peers. I tend to think it’s because being a “different” kind of black protected him in some way, as if his “otherness” made the misogyny in which he participated less threatening.

I was entering Floyd E. Kellam High School when “Shake Ya Ass” dropped. High schoolers aren’t grown, but everything happening inside of them tells them they are. And suddenly the girls had bodies, or rather they’d had them all along and suddenly I was growing more interested in seeing those bodies, hopefully touching those bodies. I hoped a girl would let me touch her, but then I learned from the older boys that you had to go for what you wanted, so I reached out to touch without permission. No small booties either, because we had learned bigger was better, even if no one could actually articulate why.

At the few parties I attended throughout high school, I watched my friends walk up behind girls, grab their waistlines, and push their hips together like they were fucking for everybody to see. I was too timid to try this myself. I’m not trying to absolve myself, as though my shyness made my other advances less harmful, or argue that because they didn’t escalate to sex they’re somehow defensible. They’re not.

One girl at my school (I switched to the newly opened Landstown High School in tenth grade) was famous. She enrolled when I was in eleventh grade. I don’t know where she came from, but I know I thought she was the most beautiful girl I had ever seen, and that every other black boy in school thought so, too, because she looked like she could have been in the “Shake Ya Ass” video. She was fifteen.

I could rewrite this as my teenage daydream, where the popular girl noticed the shy boy—we had study hall together—and he showed her there was more to her than her superficial persona, and she fell madly in love with him because he had read a book once. That didn’t happen. We were friendly, and she thought I was cute in the way you think a fall sweater is cute but leave it on the shelf because you have a drawer full of better options. One day she kissed me on the cheek, and honestly I can’t remember what led to it; I may have died that day. Another day, a few of us were gathered around someone’s CD player listening to a song and describing what the girl in the video did, and she let us know that she could do that, too—then she did. Another day, I recall, she was quiet and withdrawn. None of us asked her what was wrong, not even me with the big crush. We just left her alone.

I don’t know how she ever felt about the leering, either from us or from the grown men who undoubtedly did so as well. I know she performed for us, that she gave us material for our fantasies. I know she was desired, but I don’t know what she herself desired. I know she could shake her ass like she belonged in a video; I don’t know how much she actually wanted to. Far be it from me to suggest she didn’t enjoy her own body and the ways it could move. The fault here is with those of us who watched her and never bothered to find out. The problem is that we have consumed black girls in a way that suggests to them they do not belong to themselves.

From May 2002, when the song was released, until I graduated from high school in June of 2004, not a single day went by without someone banging out the “Grindin’” beat on the lunch room table, a hallway locker, or a classroom desk. The drums were simply the hardest shit ever committed to wax, and barring some miracle of sonic innovation I will go to my grave saying as much. “Yo, I go by the name of Pharrell,” he starts barely a few seconds in, “from the Neptunes, and I just wanna let y’all know: the world is about to feel something that they never felt before.” His introduction is interspersed with the voice of Pusha T, playful and menacing, intoning, “I’m your pusher.” But those goddamn drums—they sounded like trash can lids keeping an irregular heartbeat, or a militia horse galloping across an all-metal football field, or . . . I don’t know. They sounded like my little part of Virginia was on the map.

The rappers behind the song, blood brothers Pusha T and Malice (now No Malice), together known as Clipse, were childhood friends of Pharrell and Chad. The Neptunes produced their debut album, Lord Willin’, which was released that August. Their second album, 2006’s Hell Hath No Fury, became a major critical darling, but it’s Lord Willin’ that sounds like Virginia. Timbaland and Missy Elliott had made albums out of Virginia before, but those two were focused on the bounce—infectious, fun, light, slightly strange music that got your shoulders moving up and down on an involuntary basis. And it isn’t that Lord Willin’ lacks some of that bounce, though it moves it down a register, employing the Neptunes’ signature synth riffs in minor chords to give them a more sinister feel, focusing in on the parts of Virginia that would never make the travel brochures or tourism commercials.

“Their existence,” Jefferson wrote of negroes in Notes on the State of Virginia, “appears to participate more of sensation than reflection.” If he were here today I’d slap him with a copy of Lord Willin’ and strap him down to listen. Jefferson never intended to publish Notes. It was originally written as a response to a letter of inquiry sent to Jefferson in 1780 by the French diplomat François Marbois. Over the course of five years he gathered the information necessary to answer the twenty-two queries regarding Virginia’s geography, laws, customs, natural resources, population, religious practices, economy, and so on. The answers were published, in French, in 1785, and Jefferson then revised them for publication in English in 1787.

To the final query, about Virginia’s history, Jefferson compiled a chronological catalogue of important state papers, which he wrote “is far from being either complete or correct.” In 2016, the poet Kiki Petrosino conducted a re-reading of Notes and offered her responses to each section. To this bit she writes of how Jefferson was correct in his self-assessment, but for reasons he didn’t quite grasp: “His

account of Virginia can’t be complete without the voices of all the people whose experiences contributed to its complex history.” Jefferson wrote as he was: an intellectual, a statesman, and a slave owner. Notes is about the Virginia he could glean from such a perspective.

No one asked Pharrell and Clipse to issue their notes in the form of Lord Willin’, but they crafted them with every intention of sharing with the world. They made a statement about where they were from—where I’m from—from the perspective of young, black hustlers maneuvering a state committed to hiding its dirtiest parts. These protagonists are the dirtiest parts, supplying party drugs to the people coming to Virginia Beach as a cheap alternative to Miami. And they did so because the illegal drug trade was the only realistic avenue to economic improvement in a place where the alternative looked like joining the military. Once upon a time, Pusha T, Malice, Pharrell, and I would have been useful to Virginia because we would have tilled the tobacco fields. The Virginia we grew up in was indifferent to our existence.

On the homage track “Virginia,” Malice raps: “Ironic the same place I’m makin’ figures at / that there’s the same land they used to hang niggas at.”

When I was a child, I longed for my home to mean something, for people to pay attention to it. Well, they did briefly in April 2007, when Seung-Hui Cho shot and killed thirty-two people and wounded seventeen others on the campus of Virginia Tech. They paid a little attention in 2008, when Barack Obama won Virginia, flipping our state from red to blue and recalibrating the electoral college map. Then briefly again in 2015 when Martese Johnson, a black student at the University of Virginia, was beaten bloody and arrested for misdemeanors he did not commit.

They really started paying attention in 2017, when a few hundred white men in khakis and polo shirts, carrying tiki torches, marched through the campus of Jefferson’s school and announced, “Jews will not replace us!” This was the vanguard of a resurgent Nazi/white supremacist movement, emboldened by the election of Donald Trump, responding to calls for the removal of a statue honoring Confederate general Robert E. Lee. Growing up I knew little of who Lee was, but I recognized his name because in Virginia, until 2000, we officially recognized Lee-Jackson-King Day—that is, one day honoring Robert E. Lee, Stonewall Jackson, and Martin Luther King Jr. The white men in khakis gathered to defend Lee’s legacy of treason and protecting slavery. The next day was the Unite the Right Rally, where thousands of white supremacists marched through Charlottesville’s Emancipation Park, which for many years was called Lee Park. The counter-protestors who showed up were met with violence. DeAndre Harris was beaten in a parking garage with metal pipes and wooden slabs. Heather Heyer was killed when James Alex Fields Jr. rammed his car into a group of counter-protestors half a mile away from the rally site.

A few months later, Ralph Northam bested Ed Gillespie in the Virginia governor’s race, an important win for Democrats not wanting to lose ground to Republican candidates who had cozied up to the Trump agenda. But only a year after Northam took office, there were calls for his resignation after photos surfaced from his 1984 Eastern Virginia Medical School yearbook that show two men, one wearing blackface and one a Ku Klux Klan robe. The photo of the two figures standing next to each other appeared on Northam’s yearbook page, though he denied appearing in it. Meanwhile, several women came forward with sexual assault accusations against Lieutenant Governor Justin Fairfax, who would step into the governor’s seat if Northam were to step down. (Despite these indignities, at press time both men remain in office.)

I moved from Virginia to Brooklyn in 2013; I believed that I could not be a real writer unless I lived in New York City. So, like a cliché, I packed up and moved north. As I drove the U-Haul up through the mid-Atlantic and the northeast, Pharrell often came on the radio. It had been five or six years since he had produced any major hits, and even longer since the time the Neptunes were responsible for nearly half the songs on the air. Pharrell was supposed to be done, moving into a quiet phase of his career where the heat had died down but he remained respected. He could be an elder statesman.

But the electronic duo Daft Punk called him in to cowrite and do feature vocals on “Get Lucky,” and Robin Thicke employed his production talents for “Blurred Lines,” and suddenly Pharrell was not just back on the radio but battling himself for the number-one song in America. He seemed to be having fun and I was happy for him. By then, Pharrell had become more than a hit maker. I chose him as my connection to Virginia because he made the state seem more meaningful, like more than just a place where I had to live. Other famous, talented people are from Virginia, but the athletes had been claimed by other places (Allen Iverson to Philly, Michael Vick to Atlanta), the other musicians were more associated with sound than place (D’Angelo, Timbaland, Missy Elliott), and others were simply not as relevant to me (but much respect to Arthur Ashe and Warren Beatty). It was nice to have Pharrell along for my ride to a new life.

“Blurred Lines,” though, caught an enormous backlash. Not just the legal battle presented by Marvin Gaye’s estate claiming the song took too liberally from Gaye’s 1977 hit “Got to Give It Up”—the estate was ultimately awarded $5.3 million in damages with royalties for copyright infringement—but from feminists who thought the lyrics had little respect for the rules of consent or women’s bodily autonomy. In the controversy, Thicke was the villain, the creepy misogynist who had done wrong by his then wife, actress Paula Patton. Once again, Pharrell was relatively untouched by the rancor.

Perhaps—no, certainly—I had chosen him because I hoped to have some of that absolution, as well.

I have watched the national interest in Virginia unfold from a distance, unsurprised by the events themselves, as the state so in love with its origin story has seemingly failed to grapple with the founding contradictions and dehumanizing ideologies of white supremacy and violent sexism. And I’ve felt the sadness of having my teenage dream come true—Virginia means something now, but that meaning has swelled from our nation’s unrest, a reality that has frightening implications for the livelihood of the state’s most vulnerable. It is still Jefferson’s Virginia (Petrosino writes: “He’s the shadow I can’t quite catch, a mean glint in the mirror”). What I mean is that Virginia is still rhetorically committed to democracy, liberty, justice, and equality, while it fails at realizing any of those ideals, unable to recognize its internal contradiction. It is a confused place, but its confusion is of its own making, through its stubborn insistence of only caring to remember its past glory.

It’s Virginia. It’s where Pharrell is from. It’s where I’m from. It used to be important. It’s becoming so again. People are paying attention. Welcome. What took y’all so long?

Enjoy this story? Subscribe to the Oxford American.