Courtesy of James K. Williamson

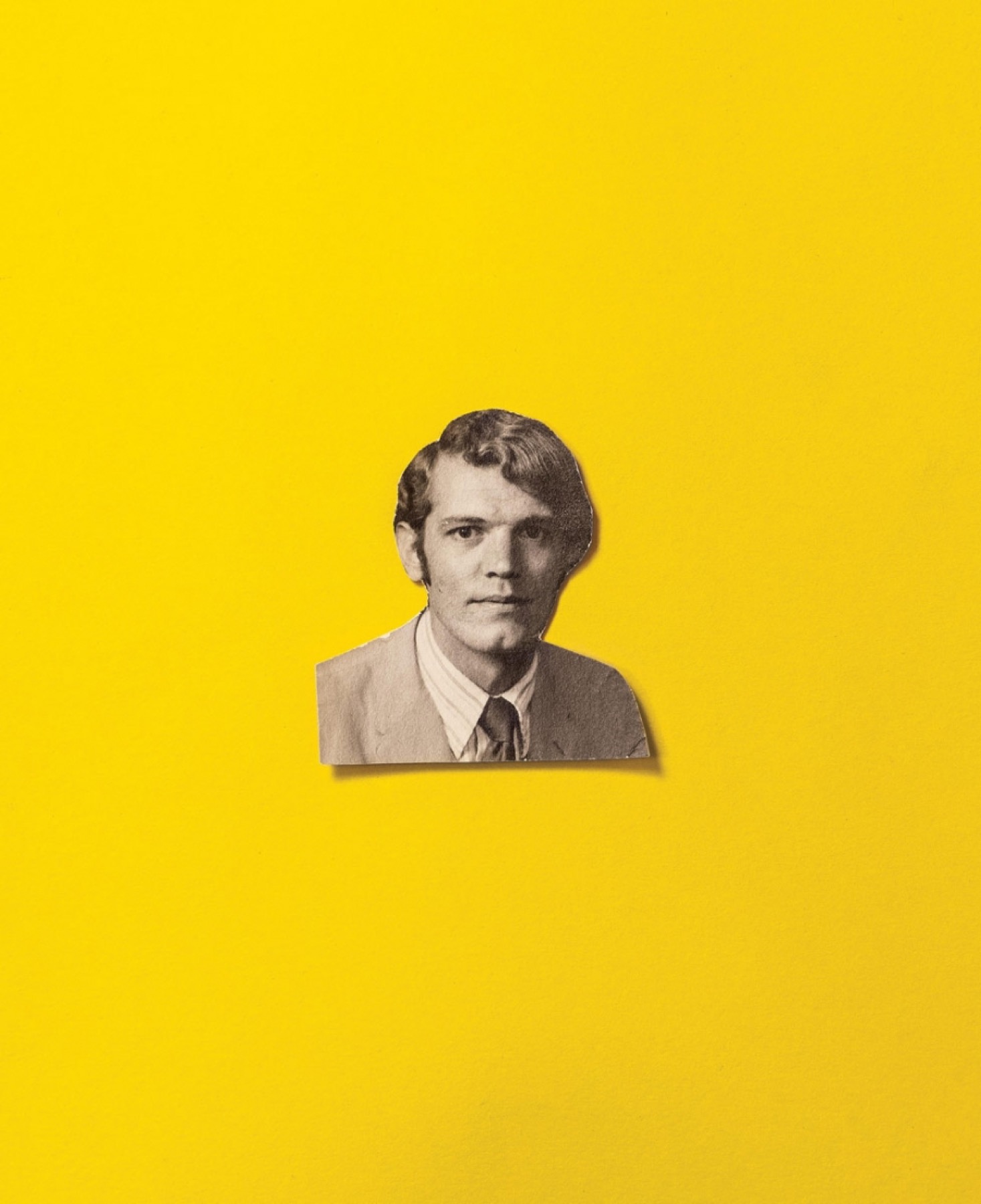

Everything He Wrote Was Good

By James K. Williamson

The pieces of Johnny Greene

As you know, I believe that when two choices are available, one should take the more dramatic, and always at a football game, pull for the side which has the ball.

—Letter to Martha Jane Patton, November 5, 1971

They formed an intermittent friendship and their sporadic correspondence lasted decades, through various chapters of Johnny’s unstable, peripatetic, and short life. Keith’s early hunch was right—almost. Johnny became a journalist whose work for newspapers and magazines—including Harper’s, Playboy, the New Republic, the Los Angeles Times, and People—focused on civil rights and gay rights and environmental destruction and Southern politics. He wrote on a breadth of topics during his two-decades-long career: articles about voting rights in Selma, GIs and prostitution in North Carolina, an offshore oil rig explosion in the North Sea; profiles of Pat Buchanan, Edwin Edwards, George Wallace; investigations of the Klan, of water usage in Georgia, of landfill contamination in rural Alabama; essays on the Reverend Jerry Falwell’s Moral Majority, on Jimmy Carter and the Democratic Good Ole Boys, on life inside the AIDS epidemic; and first-person experiential reporting on underground social movements from New York to Birmingham. But he never published a book, despite an alleged manuscript; he never became a household name—a Marshall Frady or Willie Morris, who wrote on similar topics for the same publications—and few in his immediate family understood him or the journalistic undertakings that consumed his life.

He died at forty-three of complications from AIDS in 1990, when I was two years old. His legacy and writings have been forgotten, misremembered even, by close family and friends. I had heard of Johnny in passing, and when I started my career as a journalist I asked my father about him. My father directed me to disorganized moldy boxes of old letters in our basement and he began unraveling his memories of Johnny, whom he had not dwelled on in years.

Johnny arrived in Darlington that November, and my father and grandfather drove him to an old graveyard containing headstones of shared ancestors. My grandfather also took them to a relative’s house to see the window pane that Johnny’s great-great-great-great-grandmother Elizabeth Rogers Poellnitz had etched her autograph into with a diamond ring before leaving for Alabama in 1834 (an anecdote Johnny used for a story later). Johnny’s obsession with genealogy and heritage was a defining theme of his life and career as he sought to chronicle history and his place in it, presumably fueled by feelings of dislocation in his family and in society as a gay Southern man. That evening Keith and Johnny drank at a local beer joint where Johnny proceeded to speak in a British accent. “He was a very unusual guy, the first time I met him,” my father said. “He was strange, such a showman.”

I hate Demopolis. I sure wish we lived in Eutaw, even if people do stare at you a lot, or Montgomery. As you said, people always look for the bad here. Just like Peyton Place to me, very evil. Everyone here is crazy, or just on the verge of it.

—Letter to Dorothy Greene Williams, February 5, 1961

Standing in the shallows of the Tombigbee River in western Alabama, Johnny held a crystal darter fish in his hand, a rare native species. The current swept between his legs and he admired the sunlight shining through its transparent scales. He was reporting on the river for Harper’s in the summer of 1976, following ecologists, hassling river development authorities, researching geological and economic history, and exploring the river’s twisting oxbows, chalk bluffs, and tributary creeks. That fall, holed up in the Hotel Chelsea in New York, he crash-wrote the first draft of an impassioned fifteen-thousand-word indictment of the Tennessee-Tombigbee Waterway, an obsolete barge canal project dubiously resurrected during Nixon’s “Southern Strategy.” The aim of his reporting, he later said, was to present “the feeling of what it’s like to grow up on the river, and then to see the wholesale destruction of it by brainless promoters in double-knit leisure suits, all for the blind Baal-worship of the words ‘progress’ and ‘industry.’” The story ran in April 1977, titled “Selling Off the Old South.”

The Tombigbee always loomed large in Johnny’s imagination, owing to the 1887 wreck of the side-wheel river steamer William H. Gardner, in which eight of his ancestors drowned. For Johnny, the canal project represented a rejection of not just common sense, economic prudence, ecological balance, and the public trust, but of the foundations of his own identity. In carefully accumulating detail, his article mines the experiences of his thirty years of life—lessons learned from a summer job loading lumber onto river barges; memories of civil rights crusades with the Selma Inter-religious Project; stories of growing up downriver in Demopolis—and examines Alabama’s political and social histories closest to the river’s edge. It was a futile endeavor; the canal was bound for construction in the face of so much history, science, and public protest. He concludes the story on that summer day in the river, a scene which reads as elegy:

The crystal darter flipped wildly about in my palm, and I wanted to squeeze the fish until it dissolved. There was no more I could do to save it than I could to save the river which had given substance and meaning to my life at almost every turn that I had taken.

By the time Harper’s published this benchmark piece, Johnny was thirty-one years old, jittery and lanky, more than six feet tall, and had worked as a journalist for a decade, in Alabama, in New York, taking posts and assignments from Charlotte to Norway. Editors saw him as youthful but dependable. Lewis Lapham, the longtime editor-in-chief of Harper’s, assigned him as a contributing editor of the magazine, a distinction he held for five years. “I trusted Johnny; I liked his sensibility,” Lapham told me. “Very early on, you hear a writer’s voice and you understand the first-person singular. . . . It was because of the way he writes.”

Johnny was an exemplar of the New Journalism of the time. “I generally try to write about what I’m doing and experiencing, so I can get somewhere near the truth of the matter,” he told Contemporary Authors in 1980. Another editor, Jonathan Larsen, praised Johnny’s reporting. “In profiles he could establish presence,” Larsen said, “to make a static interview come alive.” Linton Weeks, who worked with Johnny at Southern Magazine, wrote in an email, “Johnny Greene was a sharp, yet sensitive, reporter and a sensitive, yet sharp, writer. To an editor, that’s a rare and valued combination.” Across his writings, you see Johnny’s signature style: he infused his observations with the insistent pull of history. Like this two-sentence paragraph from “Selling Off the Old South” describing the river’s centrality to local ways of life:

But though the river no longer serves as passage from town to town, its life goes on. The Tombigbee continues to dictate to cattle farmers when they must move their herds to higher ground, children still learn to swim alongside the river’s sandbar and gravel-bar peninsulas and islands, and on summer Sunday mornings from distances up to a mile away, the long, slow, plaintive songs of white-robed Baptists can still be heard and sought out, the unaccompanied voices of the church’s members rising and falling, carried down the sheer, unperturbed river as effortlessly as the candidates move forward, one by one, to be immersed in the greenish-brown water.

Johnny used place as a recurrent theme, along with displacement. As a journalist, he was fascinated by communities, by groups of people and the environments which shaped them. As a person, his roads always led back to Alabama.

John William Greene Jr. was born in Demopolis on July 24, 1946. His mother, Frances Jones Greene, arranged for a cesarean on her birthday. (He complained of this late in life, “I’ve never had my own birthday. It’s always our birthday.”) He was her special child, his hair auburn, eyes brown. Frances, whom he called Muney, was a loquacious woman and an intense mother. She clung to him; he was her confidant. His only sibling, Dorothy, was five years older. Their father was reserved and often out of the house, on his cattle farm or out at the stockyard. It was a female-dominated household, with Johnny’s maternal grandmother living there, too. And like most white families in Demopolis, Johnny’s family hired a black nurse to care for him.

Dorothy remembers him as difficult, “an accident looking to happen.” Every day was a new problem. “I was just an easy child to raise and he was a hard child to raise,” she said. “They didn’t know what to do with him.” One relative shared an early memory of little Johnny as something of a fabulist, singing, “Here comes Johnny Greene from New Orleans, eating those juicy collard greens,” already narrating a fantasy of elsewhere. His mother’s side of the family sparked his interest in history and origins that pointed beyond Demopolis. According to a mid-career profile, he decided to be a writer at the age of six.

The civil rights movement and tumult of the early 1960s carved an awareness in him, which he later described as a gradual awakening. One hundred miles southwest of Birmingham and almost exactly halfway between flashpoint cities of Selma and Meridian, Mississippi, Demopolites experienced the major events of the movement with both an intimate proximity and a distinct remove. Johnny described it in a 1971 autobiographical essay, “Put Your Heart in Dixie or Get Your Ass Out”:

The civil rights movement did not begin or end on any particular day. Perhaps it never has ended. In a way, it might not even have begun. But for those of us in the small town of Demopolis, Alabama, who had heard vague details of a bus boycott in Montgomery and lunch counter sit-ins in Charlotte, the great drama of demonstrations and marches never materialized. We grew up unaffected by the movement, but in its shadow. Even if it had begun we were oblivious. Alabama beat Auburn in football, Auburn beat Alabama in basketball. There were dances to plan and attend, hay rides and picnics, club meetings and Saturday afternoons in Baily’s Drug Store.

But whether they wanted it or not, the movement touched Demopolis. “I cannot single out any one particular moment when,” he wrote, “I decided to become active in the civil rights movement. Maybe I never did.” Johnny snuck away to watch the buses of bandaged Freedom Riders pass by town; one night with friends, he witnessed police club a defenseless black woman. His mother tried in vain to dissuade him from activism, fearing the protests and the “white trash” that came out in response. His senior year in high school, Johnny campaigned for YMCA Youth Governor; he lost (“by a landslide”), knowing too well his speech did not align with local perspective: “Alabama must learn that there are some rights greater than States’ Rights. . . . We must realize that human rights are more important. We must stop being violent, we must learn that as a people committed to violence we bear the conscience of the nation.” When he left for college, Dorothy said, Johnny had few friends in Demopolis. He was apparently not hiding his sexual orientation (when she was in college and Johnny was still in high school, Dorothy said she told their parents he was gay). He later compared his hometown experience to Camus’s The Stranger. “Because I had black friends, most whites wanted nothing to do with me. Very often I felt completely isolated.”

In the fall of 1964, he went to the University of South Carolina, but found that he didn’t fit there either. After visiting my father’s family for Thanksgiving, Johnny grew restless and drank heavily. In a belated thank-you letter to Keith posted in January 1965, he described visiting New Orleans over winter break (“It was a mad house and everyone got bombed”). According to Dorothy, he had overspent his budget. The next letter came in May, with Johnny in apparent crisis: “Guess you think I have gone slap out of my mind or something. Almost. I am in Birmingham and this is the only thing I could find to write on.” He wrote over advertisements torn from an issue of Time magazine. “Short explanation—I dropped out of school. It was too much for me to take any longer.” Johnny’s father found him a job at the lumber yard and another, perhaps through a connection, as a copy boy at the Birmingham News.

He didn’t write to Keith again until the fall of 1967. “Of course I am still as extreme as ever, but Carolina was not very good for me.” He had settled back in Demopolis with little independence, to attend Livingston College while reporting for the White Bluff Chronicle, writing a Cholly Knickerbocker gossip column and filing movie reviews, which show him honing his voice and acuity, as in this assessment of The Sound of Music:

What intellectual substructure there might have been was neatly dissolved in some of the Baroque scenes, childish dialogue, and heartrending melodrama. Julie Andrews, who played Maria, the nun, proved rather definitely that poor acting can be ignored by an audience already moved to tears with sweet nothings.

In Demopolis he befriended members of the Alabama Teacher Corps, who nicknamed him “Communist John.” But his threshold of liberalism created high tensions. Differences between Johnny and his family—over his politics, sexuality, and interracial friend group—boiled over. One spring (no one can pinpoint an exact date; it was presumably 1969), Johnny hosted a clandestine party at a family hunting camp outside of town. The family found out and allegedly the party was broken up in the middle of the night. According to an ATC friend, there was a confrontation and then Johnny walked along the highway in hysterics. This incident was apparently a tipping point for Johnny, and he entered Bryce Hospital Ward, Alabama’s oldest mental institution, in Tuscaloosa. Sources from the time are conflicted about how he landed there—Dorothy doesn’t recall the details; some friends claim his family had him involuntarily committed, which was then legal. Of the many dramatic stories Johnny later told about his life in Alabama, he never published about his experience at Bryce.

At the time, more than five thousand people were housed there, among them artist, publisher, and nuclear physicist Bern Porter; other writers and artists; and a number of young civil rights activists. In Dorothy’s telling, a psychiatrist said to her, “He doesn’t ever think he does anything wrong. He never criticizes himself at all.” Johnny was committed for a medically determined period of time—at least three weeks, possibly up to a month. At this low point, Johnny called his close friend from USC, Ella Reese Hinson. “He said, ‘I’ve talked to the doctor so much about you that they gave me permission to call you,’” she remembers. “We talked for hours, and it was then that he told me he was homosexual.”

At Bryce, civil rights lawyers and activists intervened, offering guidance to young people “caught up in the system,” recalled Francis Walter, who was director of the Selma Inter-religious Project. Walter met Johnny, whom he recognized as misplaced, and helped arrange for his transition to vocational rehab; Johnny wasn’t made for cutting grass, but he could write grants. He joined the Selma Project, volunteering by day and by night partying at the Chukker, a notorious Tuscaloosa bar. “I don’t know anyone who lived life harder than Johnny,” said Richard Weaver, a poet and friend in Tuscaloosa. “When he went out for the night, you could be sure he wasn’t coming back.” Johnny described his escapades in these years as “beer-soaked escapism.” He finally graduated from the University of Alabama in 1971 with a degree in history.

In September that year, the Selma Project joined the march at the funeral procession for nineteen-year-old Margaret Ann Knott, who was run over and killed in Butler, Alabama, while protesting at an intersection in front of the town’s courthouse. Reportedly, thousands of mourners attended Knott’s funeral. Johnny wrote a vivid first-person report of the events for the Selma Project’s newsletter:

It was impossible to get inside the church, but I did manage to squeeze into the rear for a few seconds. The choir sang as I slipped back outside. There were no breezes anywhere. A lighted match was no problem, the flame did not even bend. The giant Black man who helped me get back outside announced in a loud voice, “Please clear the center aisle so we can get the corpse inside.”

Walter and others had noticed Johnny’s talent (Francis is a cousin to Eugene Walter, a founding contributor to the Paris Review) and encouraged Johnny to apply to graduate schools to pursue writing. Soon after Knott’s funeral, Keith received a small card in the mail, its trippy design embossed with the words MOVED TO A NEW GROOVE . . . Inside, Johnny had written only his new phone number and address in Manhattan, at Ruggles Hall on 114th Street and Amsterdam Avenue, across the street from Columbia University’s herringbone brick campus. He later recalled, “I was on a civil rights march in backwoods Alabama when I received my scholarship to go to Columbia.”

Courtesy of James K. Williamson

Courtesy of James K. Williamson

I’ve just about decided one of two things: (1) I have a special tendency to meet crazy and weird people, or (2) every single person in New York is either crazy or weird.

—Letter to Martha Jane Patton, October 18, 1971

“Unlike Willie, my plane never turned ‘North towards Home,’” Johnny wrote in a letter to a friend in Alabama, referring to Willie Morris’s bestselling 1967 memoir. Morris, who was from Yazoo City, Mississippi, and edited Harper’s from 1967 to 1971, considered the 1960s New York literary world one “of awesome brilliance, even when its brilliance was a little predictable, and excepted for three or four notable operators, not very colorful.” Morris later reflected, “To escape the South—all of what it was and is—I would have to escape from myself.”

Johnny went the opposite of Morris. He refrained from diving into the New York literary scene—“a slicker lot than the Chukker crowd.” He found work as a typist at the American Civil Liberties Union and, in his spare time, read the Atlanta Journal-Constitution (according to a letter, it was the only Southern newspaper Columbia’s library kept stocked) and indulged in Alabama sports clips his mother sent, hiding from the “groans and growls of New York.”

In a breathless letter to his friend and fellow Selma Project volunteer, Martha Jane Patton, he described an incident at a dinner at the Park Avenue penthouse of a Cue magazine editor, who called Johnny out: “Do you enjoy playing the Alabama hick?”

Johnny shot back, “I notice your mama and daddy never taught you how to hold a knife and fork.”

And somehow, that did it, that just about did it for me . . . I was just about too tired of being rided cause I’m from Alabama and everybody looks at me like “Where did he lose his translator?” when I ask for anything, even a piece of gum or candy.

In multiple letters, he compared New Yorkers to the patients he had encountered at Bryce—“terribly passive, spent, faces.” Just as he had in Demopolis, in New York Johnny found he was an outsider—and as in Alabama and South Carolina, he was treated like one.

Yet, at Columbia, he was being molded as a writer and he bloomed in the nonfiction workshops. “Columbia remains dear to my heart,” he wrote to Patton. “My writing class is like group therapy.” He completed his MFA in 1973 and then moved to the journalism school (of which I am an alum). While there, he picked up stories for the New Times, a young magazine championing the New Journalism mode. His career had begun to take off, somewhat to the chagrin of his professors. Years on, he relished in the story of how he had been reprimanded for skipping class while on assignment for the magazine in Washington, D.C., interviewing Nixon cabinet members during the Constitutional crisis:

One of my professors at Columbia Journalism tried to can me because I cut his class in order to interview Bryce Harlow. He was mad because the subject of the seminar that day was “How to Conduct an Interview.” And when the professor put the heat on—to the point of trying to have me booted from school—the editors of New Times had to call the dean of Columbia Journalism to see if they could “get Johnny excused from class in order to conduct interviews at the White House.”

Johnny didn’t finish out his stint at the journalism school, but by the summer of 1974 he was nonetheless a full-fledged writer and reporter, acting as a kind of Southern correspondent for the New Times and seeing his byline on a string of impressive pieces, like the at-home profile of former Alabama governor George Wallace, who was, Johnny arrived to find, sloth-like and disabled:

“Are we going to have a lively spring, Governor?” I ask, and George turns to me. I feel a cold vacuum between us—a distance that has nothing to do with our differing politics, a space between us that has to do with pain, cold physical pain.

In New York, Johnny hopped into Manhattan’s teeming scenes of absurdity, writing a number of pieces about the flashy, affluent parties centered around Andy Warhol and the gay discotheque Le Jardin. In a 1974 feature for the New York Daily News Sunday Magazine, titled “Sojourn Among Savages,” he wrote about his double life shuttling from New York to Washington—“between the world of the fashionable and so-called beautiful people and the world of politicians.” Again, like an outsider, he witnessed his peers’ indifference to politics: “It had been a zany season for me and, rolling with it, I had found myself cut off for a while from my own generation and what it was doing to itself.” But in talking with his contemporaries, I sensed a coyness on his part, a falsity in the narrator at a remove; Johnny embraced the party lifestyle.

“He was not a timid person,” said Joe Collins, a friend from Columbia, who saw Johnny as flamboyant and larger than life, noting how Johnny played up his Southernness. Collins also said Johnny was wild and sexually risky; the pair ventured to one-dollar bathhouses in the Lower East Side: “When he got in a bathhouse and he put his stuff in the locker and put his towel around him, he marched off, saw what was there, and went to it.”

Johnny didn’t write to Keith much during these years. I’m tempted to ascribe to this period in New York a neat conclusion of his self-discovery, as a writer and as a gay man. Near the end of “Sojourn Among Savages,” Johnny captures his views on his tragic generation, that the war in Vietnam and then the Watergate scandal had doomed them. The dancing, partying, and strawberry acid—it was all an act of collective self-preservation. “Something was missing,” he wrote. “I think it had to do with learning how to swim. We were all like people thrown overboard, thrashing about in the waves. If we bobbed to the top of one wave, we knew that we might sink with another. That was all that held us together.”

If he had been living a double life, it made for a twinned blossoming:

In Washington I had learned how to catch a taxicab and get from the White House to Union Station without losing too much time. In New York, I had learned how to dance, seen my reflection in the mirrors as I danced and finally come to accept that reflection.

“I had been here before, all across Dixie, along a hundred obscure Southern highways, trying to find a place where men could love one another in a region that denies them that love.”

—“The Male Southern Belle,” Christopher Street, 1978

Having impulsively taken a position at the Charlotte Observer—“to relieve a fit of pique”—in July 1974, Johnny drove out of New York overnight to North Carolina in a rented maroon Camaro. He plastered a poster of the Rolling Stones’ iconic Sticky Fingers crotch in the rear window—a sexual provocation in Billy Graham country. He wrote about the trip several years later, in his long autobiographical ethnography about homosexuality in the South for Christopher Street magazine, “The Male Southern Belle.” By the time he arrived in North Carolina on a Sunday morning, Johnny was shirtless behind the wheel, speeding and drinking beer, and looking for a liaison. He spotted a man on a motorcycle, “ugly as hell and beautiful,” in a leather jacket and dark sunglasses, his ideal Tom of Finland type. He thought the rider might be giving a sign, pushing his ass slightly over the bike seat, so he took a risk.

I had to time my move cautiously. Otherwise, I might fuck up and he might cut my throat. That can happen if you land some sick number whose idea of enchantment is to expose your guts with a can opener.

Johnny scribbled a sign on a scrap of paper and flashed it: WANT A BLOW JOB? The man gave him a signal and the two made for a motel room in Charlotte. After the sex, the biker left and Johnny’s temporary fantasy of a life of open love dissolved back into constricted reality. He was overcome with the return of his displacement: “I was back in the world I loved more than any other, the South, but I could not live there. I realized I had to find a way out, fast.”

There are only three months of clips at the Observer. Tracing Johnny through his bylines, it looks like he had relocated to Alabama by the end of the year, but I can’t pinpoint his exact movements. Through the rest of the decade, he was a roving correspondent, parachuting into stories and apparently in and out of touch with family. (My father didn’t hear from him for a decade between the early ’70s and ’80s.) Dorothy remembered that when Johnny came home for holidays “he would eat like he hadn’t eaten in a month. I guess he ate when he had money and didn’t when he didn’t have money.” He was like a pinball, always changing direction. In 1977, a profile in the Birmingham News Punch described him as “slightly tired, slightly pale, slightly nervous.” A friend from Tuscaloosa, Jeanie Thompson, said, “We started referring to him as our ‘wayward son,’ because he would just show up. He was a mess. A literal mess.” It reminded me of Marshall Frady’s description of the profile reporter’s life in Southerners: “After laboring for so long as a kind of broker or magpie collector of other people’s passions and struggles, you begin to feel you are receding further and further out of any real life yourself.”

Tuscaloosa was his closest thing to a home base. An old friend, civil rights lawyer Jack Drake, offered Johnny a free desk in a law office on University Boulevard. (Johnny listed Drake as his agent in Contemporary Authors.) “He’d disappear for a year and just be gone,” Drake remembered. He noticed Johnny enjoyed shocking friends, and even strangers, with graphic details from his escapades. This is reflected in his writing; first in the memorable New Times feature “Decadence By Invitation Only” about New York’s bisexual underground, and later in Christopher Street, a gay literary magazine that began publishing in 1976 and to which Johnny contributed a column, “The Outside Agitator.” As always, Johnny enjoyed divulging his personal life for narrative drama and as a footing for his societal critiques. As he wrote to his friend and editor Helen Rogan, “I need the bread, can bear some more notoriety and am committed to the cause of the gay male macho.”

“The Male Southern Belle” had little pretense of keeping a professional distance from his subjects, its nonlinear storyline ranging from swinging with a roommate in Tuscaloosa to affairs with a young man (also from Alabama) in London. There’s lust and love, and the dangers and thrills of cruising, underpinned by analysis parsing the region’s gay lifestyles, especially his pity for “extremely vain and excessively effeminate” men, whom he dubbed “male Southern belles,” saying:

The South was a region in which there was nothing gay about being homosexual. The male Southern belle was a victim of the South’s ruthless, snickering petulance, a survivor in a land of belligerent, latter-day Confederate cadets. And if the effeminacy of the male Southern belle was overt, it was also his only protection, as Darwinian as the fluid skin colors of a lizard.

Even though he critiqued aspects of Southern gay culture, Johnny wrote in defense of the gay community at large. He devoted one “Outside Agitator” to calling out Thomas McGuane’s latest novel, Panama, a cocaine-frenzied romp in Key West, for its “inconsistent, frequent, and oddly personalized cheap shots at gays—male and female.” Johnny met and liked McGuane (along with the novelist Jim Harrison) in Key West, and so he was surprised by the egregious characterizations of gay culture. In his usual layered manner, he cut his criticism with first-person memories and a sharp dissection of what McGuane had overlooked, the context of that specific place:

McGuane chooses to attack gays as “drunken queens” and “terrible fruit flies”—when the gays who “bump their bottoms frenetically” are actually the true anarchists in Key West, the real outlaws in Florida and every other state that has legislation against homosexuality.

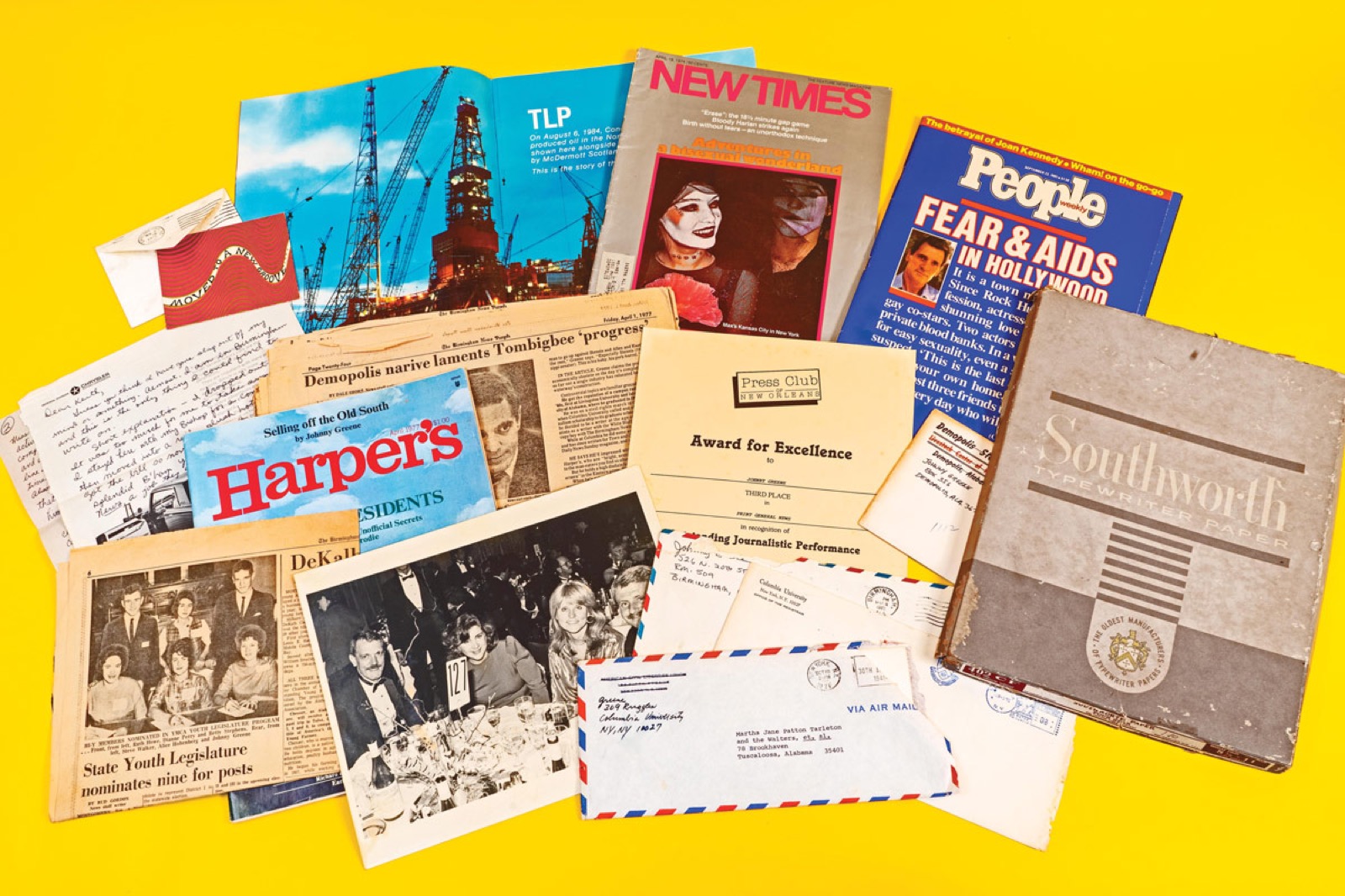

Friends swore Johnny could type one hundred words per minute, and by the end of the 1970s, approaching the height of his career, he had hit a high mark in production. “Johnny was like extreme journalism,” Thompson told me. “He wasn’t like Hunter S. Thompson, but for Alabama he was walking out on an edge.” His reporting and essays were durable at every angle, his journalistic interests expansive; while he was writing “The Male Southern Belle,” he was following up on the Tombigbee River story for Inquiry and beginning to report out the slaying of civil rights activist Viola Liuzzo for Playboy. Writing his portrait required that I interview more than thirty people from different acts of his life, because this was how his friends, colleagues, and family members remember Johnny: in pieces. (Martha Jane Patton knew him up to 1974; Keith heard nothing for nearly a decade; Dorothy mostly interacted with him at the beginning and end.) Throughout my six years of interspersed reporting, building his archive in my spare time, it has felt like being in on a secret that only a few people know. From what I know now—and this is a safe bet—no one has collected all the works of Johnny Greene.

With all of the travels I’ve had this past year I had somehow forgotten that even when cousins are distantly related, as we are, that family is just something for which there is no substitute.

—Letter to Keith, November 15, 1982

Dorothy was unsure which of Johnny’s belongings she had in the attic. In my mid-twenties, while living in Little Rock and Austin, I stopped by her house in Demopolis on drives home to South Carolina. From what I understood, few of Johnny’s possessions existed (Frances, who held on to things, died in 2002), but Dorothy said she saved boxes of his papers. I hoped to find something tangible to connect to the scattered memories and writings I was collecting in my research.

In 2013, I wrote Dorothy a letter to ask about Johnny; when she didn’t respond, I called. Clearly memories of her brother caused Dorothy discomfort. “When the subject is Johnny, I never know WHAT to expect,” Dorothy wrote in an email. There was a common refrain throughout our conversations: “I just didn’t know what he was thinking; we were just so different.” She distanced herself from him and from their mother, for fear of being engulfed in their disputes and tensions. But over the time of our correspondence, Dorothy showed a curiosity about his writing and Keith’s letters. She wanted to know if I could send her articles I’d found; she mailed me his 1987 address book, which led to a critical cache of letters from his former editor at Harper’s; she forwarded Johnny’s old friends to me, those who had reached out to her searching for Johnny; she provided me with Johnny’s detailed biography from Contemporary Authors. On my third visit, late in the summer of 2016, I was finally able to go up into the attic to look for whatever remained of Johnny.

It was September and the attic was like an Alabama sauna. I stepped carefully through the narrow maze of boxes storing Dorothy’s wedding china, her son’s old toys, bouquets of Christmas holly, her grandmother’s sock puppets, old copies of Inside the Auburn Tigers magazine. After a few hours of excavating, I finally found a plastic container labeled johnny’s things. We moved it to her dining room, where she covered the table with a bedsheet. Opening the lid, I watched a silverfish bug scramble out of an old Southworth typewriter-paper box. Underneath were framed letters from Richard Nixon, George Wallace, and Eisenhower aides. Dorothy pried the frames open and reminded me again that she was nothing like Johnny.

By the next afternoon, we had discovered another box and bag of johnny’s things. In her quiet living room, we sat in silent exhaustion. Pieces of the attic’s white insulation littered the rugs. I held physical copies of his stories, all decently preserved. Dorothy wore her reading glasses and studied an old letter. She seemed to be discovering her brother right alongside me. “Normally he didn’t confide in me and I didn’t confide in him,” she said to me recently. “We went through so much with Johnny through the years.”

He was seen as “ultra”—to use the word of a relative, who requested not to be named in this article—with an outsize personality. My father had described him to me as eccentric—strange, but innocent. Other family perceived Johnny as a bullshitter (some still do); Dorothy said he had delusions of grandeur. The same relative didn’t think he wrote about the family with wholesome truth, and that if he could exaggerate a story to woo his editors, he would. There was also tension in that his work as a roving reporter did not fulfill the traditional idea of a job or trade. So I was met with hesitance and reluctance from family initially, their memories of him less fond than those of his friends and colleagues.

In one of my many conversations over the years, a relative of Johnny’s compared him to Sarah Cameron, the mysterious central character in playwright Lillian Hellman’s 1980 experimental memoir, Maybe. The remark felt like a breakthrough in my research, a literary analogue of Johnny, someone who also had a fanciful, unknowable life. Hellman struggles to understand her acquaintance Sarah, a globe-trotting femme fatale who blends into the author’s memories over forty years, with unexpected run-ins from Paris to New York. She cannot manage to complete a full portrait. “I do, of course, remember many things about Sarah,” Hellman writes, “but often what I do think I know does not fit what I heard from her or from other people when they talked about her.” When she fact-checked Sarah’s tales, she found them prone to illusion. “But there are memories I have of her that I know to be accurate, although, as I have said before, I do not always know what she was saying or if what she said was sometimes based on her fantasies or the fantasies of others.”

Johnny appeared in spells, his relatives seldom seeing him for any extended time. Had he been friends with Jasper Johns in New York, as he wrote in his letters? Was he actually writing a piece about Darlington for the New Yorker? And did it include a fishing story about a squirrel-eating bass? What about tripping on acid in New York with a one-armed man named Richard? The Sarah Cameron allusion seems to have somehow been planted for me by Johnny himself, speaking down the years. “Of course Lillian Hellman came up,” said cousin Bubba Lyles, one of Johnny’s true believers. “He was a personal friend. He told me he had dinner with her. He would drop names.”

Johnny’s correspondence with friends usually dried up. Patton, for instance, lost track of him in the mid-’70s. An old friend of his from the Alabama Teacher Corps was completely unaware they had lived in New Orleans at the same time, in the 1980s—a missed

connection made even more improbable because they both worked on offshore oil rigs. And what about the woman he described in “The Male Southern Belle,” the one he named “Susan,” his co-conspirator on sexual exploits in Tuscaloosa. Is she the “Alice” whom he refers to in letters? “Alice sends her love, although she regrets that since she and I are no longer, we three cannot again form a multitude and share in the body and blood” or “Alice has gone and married herself off to some dude, so my fun and games are over, with respect to her.” And there have been unconfirmed appearances that sources swear by, like Johnny attending a roundtable on David Brinkley’s morning show in the 1980s.

I often think about what Dorothy said that day at her house, after we opened the plastic container from the attic: “You know him better than I ever did.”

I have asked the question “Doctor, do I have AIDS?” so often it is now a refrain that sums up my whole life.

In 1981, Johnny moved to Washington, D.C., to be an editor at Inquiry, a libertarian magazine published by the CATO Institute. One reporter he oversaw there, Keith Schneider, recounted a memorable meeting the following January. “I’ll never forget going to Inquiry’s offices in Washington,” he said. Johnny was reading the New England Journal of Medicine’s new report on cytomegalovirus, which studied four previously healthy gay men who began to have recurring fevers, swollen and infected lymph nodes, intense pain swallowing, and blurry vision—symptoms that could be misdiagnosed. Today we know that CMV is prevalent in populations with high risk of contracting HIV, though at the time AIDS was still underreported and little understood. Schneider recalled that Johnny looked up from his reading and said, “This is what I have.”

While in Washington, he sought treatment at the National Institutes of Health, which he described in a letter: “they seem to feel it’s just one of those opportunistic infections that hit people like me who have impaired immunological systems.” He had reconnected with my father for the first time in years, visiting my parents in Darlington. “Once he started going downhill, I could see it wasn’t Johnny anymore. It was a different person,” my father said, thinking of the last time he saw Johnny, around 1985. “To see a person that young become a wisp of themselves was real sad.”

By then, Johnny had left Inquiry and moved to New Orleans, where he truly settled down for the first time. He worked as an editor of Jaramac, an in-house journal of the offshore oil construction company McDermott International Inc., at times traveling to various oil rigs around the world (my father claims he wrote a musical about this work called “Tool Pusher’s Delight,” but it seems to have been lost). His CMV symptoms intensified, and according to a photo editor who worked with him at Jaramac, Johnny began missing deadlines. When he traveled, he had a prescription pill regimen. He eventually walked with a cane. He attended the Ochsner Clinic near New Orleans, but doctors were stymied by his combination of symptoms—it was, he wrote in one letter, “a disease no one there could diagnose.”

In 1985, the managing editor of People, Patricia Ryan, asked if Johnny would write an essay about his condition and his fear of AIDS. Hal Wingo, one of the magazine’s co-founders, told me that Johnny’s essay was “one of the more powerful pieces that we’ve had around.” He described it as a “breakthrough moment,” and said it was “a piece of work that we felt honored to publish.”

Each morning I wonder if this is the day purple spots indicating Kaposi’s sarcoma will appear on my legs. Frequently I set my alarm clock for odd hours to wake and see if I am sleeping through a deep night sweat. Daily I search my neck and body for swollen lymph glands. I monitor my weight, and each ounce I lose throws me into a tailspin, doubling my doubt and uncertainty.

Few staff members at Jaramac spoke to him after the People piece ran. Some said he was brave, but most turned away. The essay was published on June 17. By the end of that week, he was fired for “low productivity.” “Funny how that hadn’t been mentioned before,” he wrote shortly afterward in an op-ed for the Los Angeles Times.

It is true that people all over the country are being fired from their jobs because they have—or might have—AIDS. I’m not talking about high-risk jobs. I’m talking about ordinary jobs where ignorance about this disease has fed paranoia to the point that people fear sharing office space with a co-worker who might be carrying the virus in his bloodstream.

A profile of Johnny in the Advocate relayed that he was working with a New Orleans ACLU lawyer, but nothing came of the case. His new beat, he joked, was dissension.

“On Monday, I’m off to Demopolis, not having seen my parents in a year and having had strained relationships with them since the People adventure,” he wrote my aunt, Kyle James. The bachelor days were thinning out. He fell into a relationship with a younger man named Charles Olts—“Charles from Mobile” in his letters—who worked as a concierge in the French Quarter. Olts is presumably the person described in a 1985 letter to his friend Helen Rogan as “the current love of my life.” As he had written in the essay for People: “I make two changes in my life immediately. I avoid involvement with those who are not as AIDS-aware as I am. And I seek out for friends only those who can contribute to the quality of my life by reminding me to live simply and appreciatively.”

The co-bylines that appear at the end of Johnny’s career are indicative of his declining health. His last pieces reflected his lifelong obsessions, politics and sexuality: for People, a profile of David Duke, and his final solo publishing credit, “Gay in Birmingham: The Apollo Ball, RSVP,” for Southern. The latter story received a strong negative reaction from readers, which was not a first for Johnny, but he was disturbed. “The level of homophobia the article unmasked took us all by surprise,” he told the Advocate in 1988. “There was nothing controversial about the article. I’m afraid it shows how . . . backward the South—and maybe the whole country—still is on gay issues.”

In early 1990, he and Olts moved from the French Quarter to New Orleans’s lakefront, where “instead of abiding drunks 24-hrs. a day, we now revel in the songs of birds and the antics of squirrels,” he wrote Rogan in February. “It is, actually, a great area in which to recuperate from my recent operation,” referring to a gallbladder surgery. This is the last letter in my archive. Dorothy visited him during his recovery from surgery and not long after, he returned to Demopolis. “I think he came home to die,” she said.

Their mother, Frances, was the beneficiary on his life insurance policy and this was his final concern. “The insurance,” he said on his deathbed, and then his last word: “money.” John William Greene Jr. died on March 22, 1990, one mile from where he was born.

After his passing, editors paid a remarkable tribute, gathering at his graveside with a small group of friends and family. “His mother was a gracious hostess and it was an honor to be included out of respect for Johnny and what he did for us, the work he did for us over the years,” said Wingo. “Everything he wrote was good.”

Wingo’s statement resonates beyond Johnny’s work in journalism; you can see it everywhere, from the fiction he dabbled in to his dashed-off notes to his letters—including one he sent his friend Steve Suitts from the Selma Project, which contained a kind of experimental narrative poem that’s undated and titled “The Letter as a Short Story, the Short Story as a Letter.” It’s a moment of perceptive emotional vulnerability, a humanness.

Marigolds. They are like marriage. They are the stems one plucks from branches and sticks between one’s teeth to gnaw on as one walks between the burning lines, the burning fire of the terraces which perch, one atop the other, over the flame-tossed sea.

I do not want to spend the rest of

my life alone.Marigolds. They are without compassion, as if compassion were meant to be a commodity which each of us understands. I have no use for marigolds, unless I can see them. Otherwise, they are just one more thing to dream about and I had had enough dreams, I have had enough dreams, already.

In a way, I guess I am free.

The last letter my father saved is addressed from London in 1986. On a postcard, Johnny crammed, “The chance to be here again, one more time, however briefly, could not be passed over.” He said he was there to write a story on the Financial Times for Town & Country; yet another missing piece. When I was born, Johnny sent a silver Mickey Mouse piggy bank; it was a staple decoration of my youth and it’s still on a shelf in my childhood bedroom. I didn’t learn of its provenance until recently.

My father was farming in South Carolina and unable to attend Johnny’s funeral at Riverside Cemetery in Demopolis, overlooking the combined waters of the Black Warrior and Tombigbee Rivers. It was not far from the graveyard my father and Johnny visited decades before, when, on a drive along cattle pastures during a dry fall season, Johnny flicked a cigarette out the window. “And I remember Johnny had not grown up on a farm,” Keith said, conscious of the dangers of dry grasses. “When he just tossed the cigarette out of the window I was thinking, ‘Now this guy ain’t no farm boy.’” His obituary in the Demopolis Times stated: “He was a writer.” Nothing more.

Enjoy this story? Subscribe to the Oxford American.