Dizzy Gillespie in 1975. © Giuseppe Pino/Contrasto/Redux

I Remember His Sweetness

By Maxwell George

I

n November of 1963, William Whitworth landed in Manhattan. The twenty-six-year-old reporter from Little Rock had taken a job at the Herald Tribune, headquartered on West 41st Street, several blocks south of Times Square. Whitworth had been, as he later remembered, “obsessed with the idea of getting to New York,” and he fell into the heady scene at the Trib, “the writer’s paper,” as the sixties swelled toward their cultural crescendo. (Among his early assignments was covering the Beatles’s first American visit and appearance on The Ed Sullivan Show the following February.) New in the city, he reached out to a local contact, not quite a friend, but a correspondent with whom he’d been exchanging letters for a couple of years—a Mr. Gillespie. Dizzy.

“He said to get in touch with him when I got to New York, and once I was settled there, I did that,” Whitworth remembers. At forty-six, Dizzy Gillespie was a living legend, the king of bebop, who had by then, as noted in the New York Times, “exchanged his youthful bopster’s image for the role of elder statesman.” Bent horn. Soul patch. Black frames. Beret. That year he was running for president (To the tune of “Salt Peanuts”: “Your politics ought to be a groovier thing / Vote Dizzy! Vote Dizzy!”). Whitworth, a jazz head and an almost-professional trumpet player himself (he had turned down an offer to join the Stan Kenton Orchestra in favor of the Trib), would soon be kicking it with his hero in clubs around the city, sharing meals and accompanying him to shows. Their friendship lasted until Gillespie’s death from pancreatic cancer in 1993.

I heard a version of this story from Bill some years ago when I was living in Little Rock. In 2015, I was about the same age he had been when he moved to New York, and Bill had settled back in his hometown after a long career at the New Yorker and then the Atlantic, where he was editor-in-chief for twenty years. That year we spent a few afternoons together at his house, talking magazines and listening to records from his collection, mostly jazz. One day, I noticed a silver trumpet mouthpiece sitting on the shelf amongst his CDs and LPs. When I asked about it, he casually explained that it had been a gift from its original owner, his friend Dizzy Gillespie.

The William Whitworth byline has been retired since the early seventies, when he switched over to editing for good. An inquiry as to whether Bill might pick up the pencil again (he favors a yellow Dixon Ticonderoga No.2) to write about his old friend for this magazine was met with a gracious but unbending rejection. But as weeks went by, I couldn’t get the image of that silver mouthpiece out of my mind, along with the idea that, through Bill’s memories, we have access to the offstage, personal side of the colossal legend of Dizzy Gillespie. I asked to interview Bill for a story of this nature. He was shy about the idea, reluctant that it would come off as inflated or inconsequential; though I knew him to be tack sharp, he noted that he was hazy on the details and his peers from that time are dead (he is eighty-two). But when I called him at home from New York, where I now live, one afternoon in June, he dug into his ambered memories of Diz and the stories came easily.

Born into humble origins in Cheraw, South Carolina, in the rural Jim Crow South, John Birks Gillespie became a famously magnanimous and jolly celebrity—especially in contrast to his fellow bop luminaries, the tragic Charlie Parker, moody Charles Mingus, aloof Thelonious Monk, and egoistic Miles Davis. “He was always such a positive, upbeat, happy presence wherever he was,” Bill said, echoing a sentiment of nearly everyone who crossed Dizzy Gillespie’s path—a “great harvest of joy,” in the words of a photographer who traveled with Dizzy toward the end of his life.

All of Bill’s anecdotes about Diz played to this theme: here was a man, a titan of American music, whose genius helped revolutionize jazz in the forties, opening the door for its great modern period—the pre-birth of cool!—and yet who carried a “personality of warmth and openness and friendliness everywhere, with whoever he was dealing with,” Bill said. “That side of him was something that I remember as strongly as I remember his musical force and power and creativity.”

In his autobiography, Treat It Gentle, Sidney Bechet, the New Orleans clarinet/soprano saxophone improviser and composer, writes about the earliest jazz, an artistic blossoming which he had participated in: “That music, it wasn’t spirituals or blues or ragtime, but everything all at once, each one putting something over on the other.” This seems an excellent and deliciously simple working definition of this art form that by its founding spirit resisted classification. “Maybe that’s not easy to understand,” Bechet continues. “White people, they don’t have the memory that needs to understand it. But that’s what the music is . . . a lost thing finding itself.” And this seems an even truer definition. Jazz as a reclamation.

In something of the same sense, Toni Morrison writes of jazz as the signal of a higher plane of creative agency for African Americans, the first sign of an evolution in self-regard (these are some of the words she deploys), expressed in the assertiveness of choice, of imaginative freedom, which she examines at the level of the culture and of the personal, as was her art, in the novel Jazz. She writes in the speech “The Source of Self-Regard” of the music’s position in American cultural memory, “the fact that the appreciation of jazz is one of the few places where a certain kind of transcendence or race-transcendent embrace is possible.” Jazz as a transformation, a threshold.

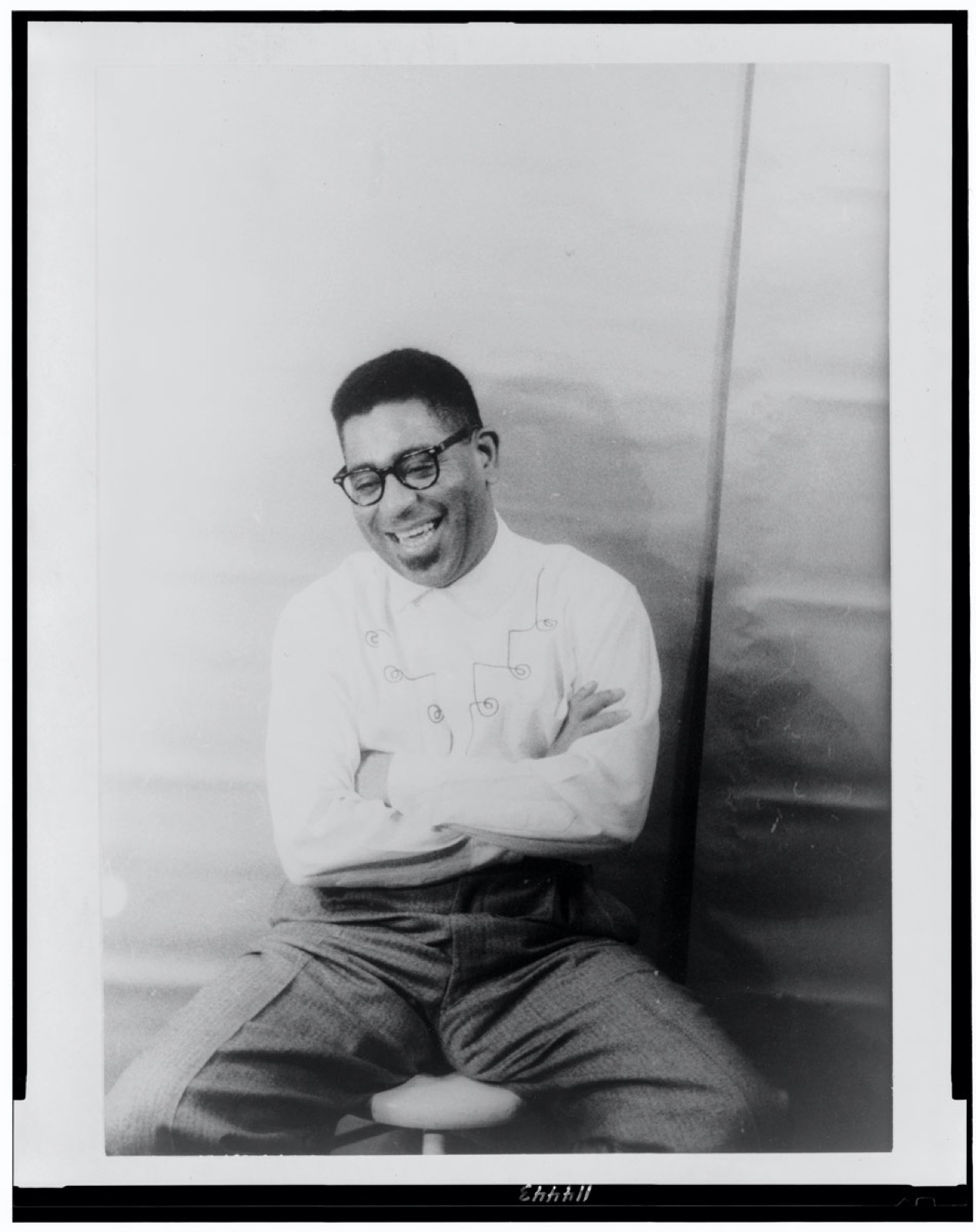

Dizzy Gillespie in 1955. Photo courtesy of the Library of Congress, Prints & Photographs Division, Carl Van Vechten Collection, LC-USZ62-114443

Dizzy Gillespie in 1955. Photo courtesy of the Library of Congress, Prints & Photographs Division, Carl Van Vechten Collection, LC-USZ62-114443

Bill and Dizzy met in St. Louis. In the early sixties, Bill was reporting for the Arkansas Gazette, his hometown’s Pulitzer-winning paper, and he heard about a weeklong stand Dizzy Gillespie was playing at a club in St. Louis and recruited a friend from the copy desk to drive up with him. “The music was thrilling,” Bill recalled. “Dizzy was still at the height of his powers.” They went to every show that week, arriving early each night to get a table in front. By the third night, they had become a curiosity to Dizzy, the pair of young white guys at his feet, and at intermission he asked what they were doing. “And we told him we were two guys from Arkansas who had taken a week’s vacation just to come here,” Bill said. “So he loved that.” By the end of the week, they were going to catch the late sets at other bars together. The next year, Bill brought Dizzy to Little Rock to perform, and the co-founder of modern jazz stayed at the Whitworth residence. Bill remembered it as an embarrassment; the audience talked through Dizzy’s set. Thirty years later, Dizzy told the New Yorker about it: “I stayed at Bill’s house with him and his mother. . . . I got a letter from Bill later telling me, ‘You should know that your being a guest in our house was a crowning achievement. . . . The sheets you slept in haven’t been washed, and all the brass players come from miles around to kiss them.’”

The exaggeration is almost believable. “I was always amazed to find myself in the presence of one of the greatest trumpet players, and the greatest jazz players on any instrument, historically,” Bill said. “You know, it’d been Louis Armstrong, and then Roy Eldridge, and then Dizzy. That was the history of jazz trumpet. It was amazing to me, to be allowed to be around him in that casual way. And it was fun, also, to see the way other musicians responded to him and the way he responded to them.” Once, they went to Birdland, the midtown club named after Dizzy’s late musical soulmate, Charlie Parker, to see Miles Davis: “We went downstairs and as the door opened, I could see Miles on the bandstand frowning, as usual, looking annoyed about something. And as we came through the door and Miles saw Diz, his whole countenance changed. He put on a big smile and he just turned into a little boy—he looked like a smiling little boy.” Bill recalled how Dizzy was always received in this manner, and how he made a point to put himself on the level: “He was a celebrity to other musicians, not just me, but to other famous musicians. So when we went into a club and the other musicians saw him, they would gather around him like fans and ask him questions. I can remember seeing him, more than once, going over to the piano keyboard to answer some harmonic question by playing chords and showing what he thought the solution was—how he would write it, how he would play it.”

Dizzy Gillespie saw himself as a kind of musical prophet. “I’d like to be known as a major messenger to jazz rather than a legendary figure,” he writes in his 1979 memoir, to BE, or not to . . . BOP, placing himself in a line of divinely inspired innovators who had advanced the music: from Buddy Bolden through Miles Davis. “There is a parallel with jazz and religion. In jazz, a messenger comes to the music and spreads his influence to a certain point, and then another comes and takes you further.” Dizzy’s understanding of his talent, his music, and his place in the world was informed by his conversion at age fifty to the Bahá’í faith, which asserts the gradual advancement of humanity toward universal fellowship. “So far as ye are able, ignite a candle of love in every meeting, and with tenderness rejoice and cheer ye every heart,” wrote ‘Abdu’l-Bahá, son of prophet Bahá’u’lláh.

“I never heard him say a negative word about any musician or any trumpet player,” Bill said, “even though I know—I just know—that he had feelings and opinions like anybody else. He didn’t really think that everybody was as great as they might think they were. But he never let on; he would never say anything negative about anybody. And so when I remember him I remember, more than his genius, I remember his sweetness. And I can’t say that about anybody else.”

“That’s the way I would like to be remembered, as a humanitarian,” Dizzy writes at the close of his memoir, “because it must be something besides music that has kept me here when all of my colleagues are dead. . . . So maybe my role in music is just a stepping-stone to a higher role. The highest role is the role in the service of humanity, and if I can make that, then I’ll be happy. When I breathe the last time, it’ll be a happy breath.”

In a way, Dizzy Gillespie embodied both Sidney Bechet and Toni Morrison’s articulations about jazz: the music as reclamation, the music as transformation. First, as an innovator, a new finder of the lost thing (or the discoverer of a novel way to describe it, with bebop) and then, later, as a measure of self-regard and of the transcendent embrace that we recognize about the music.

One of the last times Bill Whitworth saw Dizzy—maybe the last, though he can’t recall for certain—his friend was sick. Bill was back in New York, down from Boston, where he had moved in 1980 to take over the Atlantic, and he caught a set; Dizzy was playing alongside his protégé Arturo Sandoval. The maestro had lost a step. “Dizzy said to me that it wasn’t just his chops, it wasn’t just his trumpet playing that was declining, but it was his health,” Bill said. “He was barely able to play by this time.” It was around 1990, so they had known one another thirty years by then. Dizzy knew that he was dying and he wanted to give Bill a memento—one of his custom trumpet mouthpieces.

“And you’d have gone back to Boston clutching that thing closely, I’d imagine?” I asked.

“Oh absolutely. I still polish it occasionally, so that I can see his name on the side.”

Enjoy this story? Subscribe to the Oxford American.