Reference card for the Plantation Echoes recording from American Folklife Center, Library of Congress

My Father Is a Witness, Oh, Bless God

By Blain Roberts and Ethan J. Kytle

2019 Southern Music Issue Sampler featuring South Carolina

Track 17 – “My Father Is a Witness, Oh, Bless God” by the Plantation Echoes

On several occasions in the early 1930s, George Gershwin left his native New York City for the languid clime of Charleston, South Carolina. Like the thousands of tourists who visited every year, Gershwin reveled in the area’s scenic beauty during his stays—frolicking on the beach, playing golf—but he was really there to work. Gershwin traveled to Charleston at the insistence of DuBose Heyward, the local author of the best-selling novel Porgy, an exploration of African-American life in the city that the celebrated composer had determined to set to music. Heyward, who was white, reasoned that if the developing opera, Porgy and Bess, which would debut in 1935, was to sound authentic, Gershwin needed to be exposed to Gullah—the distinctive language and culture crafted by enslaved people on isolated plantations in coastal South Carolina.

On one of those visits, Heyward took Gershwin to nearby Wadmalaw Island for a private performance by a new musical group he greatly admired. Established in early 1933, the Plantation Echoes were made up of fifty Gullah field hands who enjoyed singing spirituals, most dating back to slavery. A handful of the singers were, in fact, former slaves themselves. Heyward’s praise of the Plantation Echoes was effusive. “The entertainment is not only highly unique but enlightening,” he later remarked. “There is an electrifying quality to the ‘shouting’ and the performers’ ability to shift from one time to another in perfect unison is a revelation.”

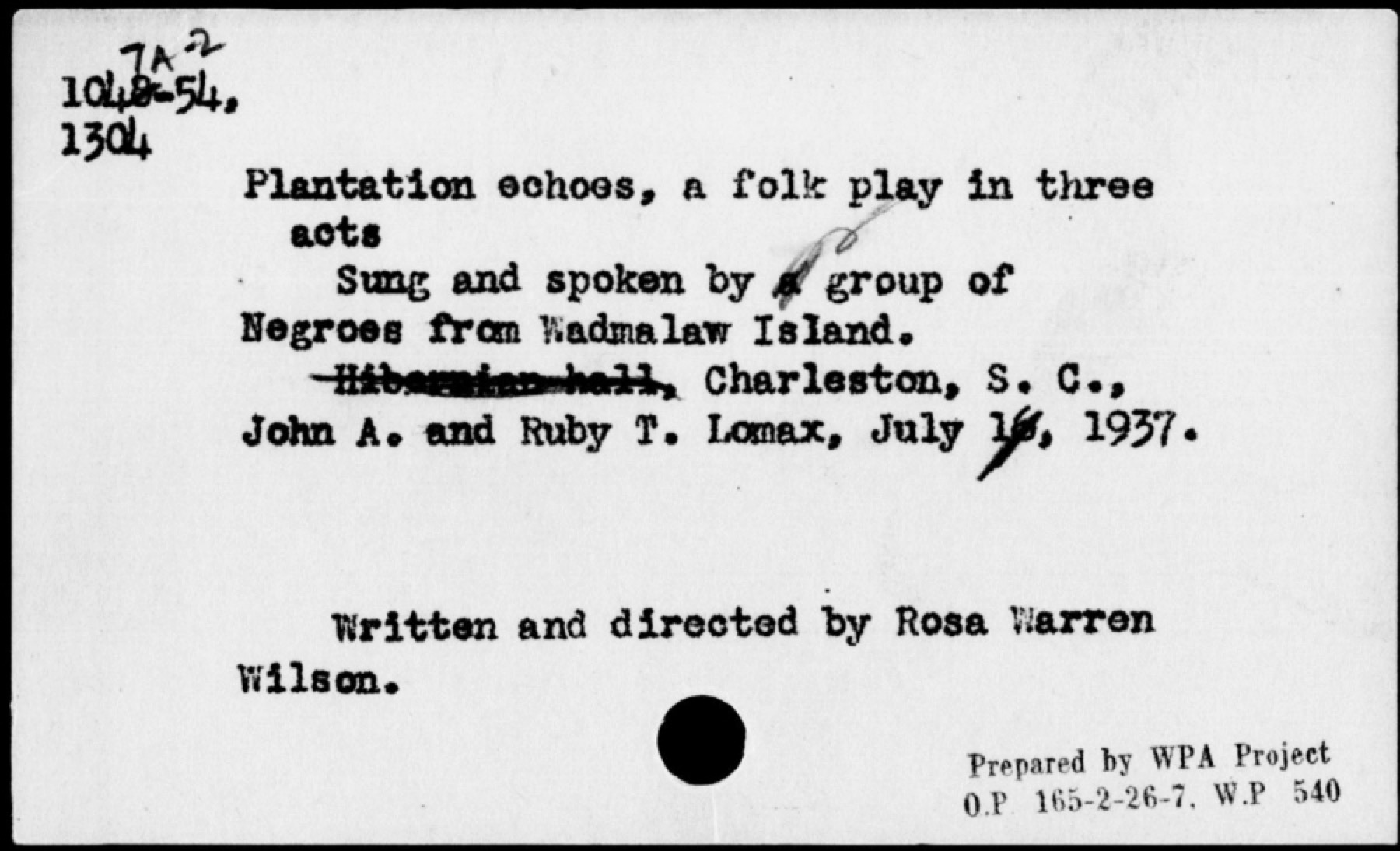

Others found the Echoes’ shows electrifying, too. “I think any American audience will be . . . moved by your singers,” folklorist John A. Lomax told the troupe’s white organizer, Rosa Wilson, after recording a 1937 performance for the Library of Congress that included “My Father Is a Witness, Oh, Bless God.” “The chorus singing and clapping both were especially natural and effective. I recommend the performance heartily.”

Produced and arranged by Wilson, who owned the Wadmalaw plantation on which at least some Plantation Echoes members worked and lived, the group’s three-act show sought to represent a cross-section of Gullah life and culture in three scenes: a spiritual meeting, a twilight burial service, and a barn dance. The stage set evoked an Old South plantation, replete with logs, cotton stalks, an imitation cabbage patch, and “an old-time plantation bell” used to call in the enslaved laborers at the end of the day. Press coverage emphasized the Echoes’ simplicity and lack of self-consciousness, as well as the group’s fidelity to the traditions of their ancestors. The first-act spiritual meeting, reported the Charleston Evening Post in 1934, “was conducted without any changes, in exactly the manner in which it has been carried on for generations past.” The Echoes were eventually featured in National Geographic and on multiple occasions invited to participate in the National Folk Festival in Washington, D.C. Into the 1940s, the group gave regular public concerts in Charleston and the surrounding area.

Three other Charleston spirituals troupes, formed in the decade before the Echoes, had already helped make the city worthy “of musical pilgrimage,” according to an Atlantic Monthly critic. Yet amazingly, ironically—perversely—the members of these three groups were white, not black. The Southern Home Spirituals and the Plantation Melody Singers employed vicious racist stereotypes; they blacked up their faces and exhibited the buffoonery that had defined minstrelsy since the early 1800s. But it is the third group, the Society for the Preservation of Spirituals, that proves the most bewildering, at least to twenty-first-century eyes and ears.

Created by descendants of slave-owning families from area plantations, the SPS rejected the trappings of minstrelsy and instead performed slave spirituals dressed in the clothes of the antebellum master class—cavalier tuxedos for the men, hoop skirts for the women. And the group’s pronouncements are equally perplexing. The SPS not only claimed that its elite white members were the proper guardians of slave spirituals; it also insisted that the songs they sang had nothing to do with the pain of enslavement. “The Society for the Preservation of Spirituals,” said SPS member Caroline Pinckney Rutledge, “is anxious to correct the erroneous, yet general impression that the Spirituals were ‘slave music’ or the ‘music of bondage sung by a race in their oppression or degradation.’” The enslaved, the SPS maintained, had been content and well provided for.

The emergence of the all-black Plantation Echoes represented a potent threat to the SPS’s claim to authenticity, and the white troupe declined to appear at Charleston’s popular Azalea Festival in 1936, unless it was to be the only spirituals group on the program. Festival organizers, for their part, were happy to showcase an all-black spirituals group if tourists wanted to hear one, and the Echoes had been popular in previous festivals.

For all the Echoes’ value, the group, as a black commodity in the Jim Crow South, could hardly escape the paternalistic assumptions and prejudices of white Charlestonians. Founder and director Rosa Wilson sacrificed her time and money to promote the Echoes—she even sold two pigs to finance their first public concert in 1933—and she had a reputation for being “soft-hearted” toward African Americans. Still, Wilson’s stewardship must have made it difficult for group members, especially for the field hands who worked on her plantation, to question her authority or her decisions. And like the SPS, Wilson believed that Gullah spirituals were as much her music as they were her black performers’. “I feel that we are greatly indebted to our foreparents for our spirituals,” she announced at the 1937 show that Lomax recorded, “for they willingly taught the old slaves the Bible and hymns which is the foundation of our spirituals. These slaves taught their children. And so on through many generations by word of mouth have the spirituals and folklore of the nigger come to be a part of the land we love, South Carolina.”

Rosa Wilson’s racist rhetoric, self-serving narrative, and brazen cultural appropriation are difficult to stomach. But she, like DuBose Heyward, got one thing right: Gullah spirituals are an essential part of South Carolina music and history, reminding us of the torment of bondage—and the hope for a better day.

Return to the South Carolina Issue liner notes.

Order the 21st Southern Music Issue & CD featuring South Carolina.