Now I Don't Know Who I Am

By Lauren Du Graf

“Games, Dance and the Constructions (Unfinished Plywood) #23,” by Teppei Kaneuji. Courtesy of the artist and Roslyn Oxley9 Gallery, Sydney

Mixed (race) feelings about Columbia’s Toro y Moi

S

o what are you? It’s a question which compels a lie. The kind that primes you for an everyday sort of fraud. A lie that is tied up with this philosophically fraught business of is-ness—the compulsion to thingify, to label, to fix in the mind rather than to deal with a far more chaotic, contingent reality.

Mixed people know this question (and this lie) well. The question is a reminder that you are an anomaly. Answering it means assenting to a sort of race math, where a set of racial fractions is supposed to amount to a whole person, like a pie chart.

When I’m asked “What are you?,” I bristle, but I bear it. The details are significant. I’m not under the delusion that I live in a post-racial world. More than almost anything, I long to be understood.

I am a daughter of a Chinese-identifying immigrant from the Philippines and a white father of uncertain origin (he was adopted). It’s a confusing answer, yawningly detailed, but an accurate one.

Are you Chinese or Filipino?, people ask. Why do I have to choose? Why, in order to be legible, do I have to be clarified, to be proven? Like a child of a Kenyan and a Kansan with an Arabic middle name. Show us your birth certificate.

I wonder how the question has bled into my psyche. The ways I’ve avoided defining myself out of a sense of spite. The ways that feeling like an aberration has made me small, deferent. The ways I’ve grasped for agency to compensate for an imagined lack. The ways I’ve tried to feel infinite.

Sometimes, I don’t feel like playing along, and just say, “I’m a question mark.”

I sense a familiar question mark in Chaz Bear (born Chazwick Bradley Bundick), the thirty-two-year-old musical polymath and visual artist from the northeast suburbs of Columbia, South Carolina, best known by the alias Toro y Moi. The name, which sounds like TORO EE MWAH, is math that doesn’t add up, except as metaphor. In Spanish, toro means “bull” and y means “and”; in French, moi means “me.” He chose the name largely for how it looked; in translation, the meaning is “pretty much nonsensical,” he has said. Indirectly, the name’s bilingualism gestures toward his mixed heritage; Bear’s father is African-American, from Virginia, and his mother, like mine, moved to the States from the Philippines when she was in college.

From his early teens, Bear had shown himself to be a precociously professional bandleader. He fronted the Taxi Chaps, a three-person band inspired by Weezer and the Specials that had gigs at a smoothie bar where their Polaroid hung on the Polaroid wall. In high school and college, Bear helmed the Heist and the Accomplice, a tightly rehearsed, two-guitar band that made people dance and sounded like the Strokes.

“The joke was ‘You could be the next Hootie,’” said Cameron Gardner, who played drums in the band. Gardner is of course talking about the most famous band to have emerged from Columbia, Hootie and the Blowfish, a band which, like Toro y Moi, also features a black bandleader and white sidemen. (In a sense, the Heist and the Accomplice did become the next Hootie, but not as the Heist and the Accomplice. Bear and the bassist Patrick Jeffords went on to find success with Toro y Moi; Gardner and Dylan Lee, the Heist’s second guitarist, joined the touring band for Washed Out, led by Bear’s friend from the University of South Carolina, Ernest Greene.)

For a time, Toro y Moi had been something of a side project, a container for what Bear worked on by himself. There was a website, a Myspace page, and some CD-Rs circulated around town. But he started reaching out to blogs, and to his surprise, they listened. Things snowballed in 2009, the first year of the Obama presidency, a banner year for mixed people. It was also the year tech companies started to cash in on digital nostalgia with apps like Hipstamatic, which muted a garish, HD reality with retro patinas. Drawing from a softly faded palette of distorted electronic textures, the music fit the mood of a generation numbed by the internet and nostalgic for the simpler technologies that preceded it. The blogs called it chillwave, a compound noun that sounded like a relaxing setting on an oscillating fan.

That same year, one week before he was going to let Taylor Swift finish, Kanye West hyped Toro y Moi on his now-defunct blog KanyeUniverseCity. West posted “Talamak,” a glitchy, intricately rhythmic track blending shoegazey textures with a hip-hop feel. On “Talamak,” Bear made use of sidechain compression, a technique which put him in dialogue with an experimental vanguard of hip-hop producers that included J Dilla, Madlib, and Flying Lotus. It was a stylistic departure from Bear’s earlier, guitar-driven music. “I was almost jokingly attempting at r&b, doing my impression of what a J Dilla song sounds like, and then it turned into what the album was,” he said. Bear was something of a late bloomer when it came to hip-hop, which he had begun listening to in college. Suddenly, Ye was cosigning, anointing the track with a five-word annotation: “LISTEN TO THIS GOOD SHIT.” Everything Toro from this point on bore the imprint of his blessing.

The song’s title referenced a word in Bear’s mother’s language that many would have found untranslatable; in Filipino, “talamak” means soaked, serious, difficult to cure. In the Philippines, it is a word often used to refer to social conditions which have become so pervasive that they have metastasized into something incurable, like the rampant brutality and corruption that followed four hundred years of Spanish colonial rule, as José Rizal famously chronicled in his great novel Noli Me Tángere. Yet, as is often the case in Bear’s music, on “Talamak” he wasn’t singing about politics, but about romance:

When can we get together again?

Nevermind, I’ve lost you

How can I tell if I love you anymore?

Nevermind, I know I do

It’s a meditation on the vicissitudes of long-distance love woven with the poetics of paradox. Absence both tests and verifies a lover’s resolve. A separated lover has doubts, but realizes a form of destiny that is rooted in the ritual instincts of the body; “it’s my body’s plan,” he sings, “make another telephone call and think of you and me.” The lyrics are sentimental, but the delivery is detached, with the vocals set so low in the mix they’re barely audible. As if the thoughts were still somewhat secretive. As if the message could disintegrate.

There’s something quintessentially Toro about this song. While there is disquiet, there are no sonic controversies, no traces of pent-up rage. It has a light groove. It is ambivalent resignation buoyed by a catchy beat, cognitive dissonance as easy listening. It’s in the palatable ambiguity that I hear a question mark, the anomalous edges of a multiple consciousness tempered by the wish to be someone you can relate to.

Earlier this year, Toro y Moi released Outer Peace, the band’s eighth album in a decade. (I use the term “band” here liberally; Toro largely functions as a solo project, with Bear writing and producing everything himself. He employs a regular touring band, but the creative direction is largely up to him.) Toro has not just beaten the average shelf life of an indie buzz band, but is perhaps bigger than ever. It is under new management, and appears to be making a concerted play for a more mainstream following and more corporate money. Bear’s doing sponsored advertorials for designer denim and Cartier. The visuals are fresh. Toro is playing the kind of music that works at huge festivals, the kind that sounds good in the club, good in a coffee shop, good on a playlist. It still has the novel aura of a band freshly plucked from the underground.

Outer Peace is funkier and more danceable than the ambient groove on Toro’s last album—the moody, breakup-inspired Boo Boo (2017)—but then again, almost every Bear project sounds different. To call it evolution would be too simple. He adopts and abandons musical genres fluidly, aggressively trying on aesthetic alter egos for size (Les Sins, Sides of Chaz, PLUM, to name a few). One project sounds like seventies psychedelia, the next, French house. As a producer, he works with an enviably cool roster of rappers and r&b singers, including Tyler, the Creator; Dev Hynes; and Travis Scott. (Bear makes a brief appearance in Scott’s new Netflix documentary, in the studio with Tame Impala, smoking a joint and wearing tube socks, quietly shrinking into the couch.)

There’s a high-achieving aptitude to it all, a certain polyglot prodigiousness. He knows how to hack and fuse genres, how to enter and exit. Part of his genius is that he’s an unrepentant copyist; for a time, his motto was a saying gleaned from Paul Rand, the graphic artist behind logos for companies like IBM and Enron: “don’t try to be original, just try to be good.” The sentiment is memorialized in a track called “Freelance” on his latest album: “imitation always gets a bad rap, man,” he sings.

Bear has a gift for mimicry that is not unlike fellow half-Filipino Bruno Mars, one of the most skilled imitators of our time, or Arnel Pineda, the current Filipino frontman of Journey, who was recruited based on an amateur video uploaded to YouTube in which he was singing cover songs with impeccable accuracy. Filipino culture is ravenously musical and deeply imitative. The music scene is dominated by cover bands, one of the legacies of hundreds of years of colonization and especially the American occupation. Imitation does not get a bad rap to a Filipino because being a copyist is not only good art but, at this point in history, traditional music. Bear also has an ear for genre melding, like the Afro-Filipino Joe Bataan, born Bataan Nitollano and raised by a Pinoy father and an African-American mother among Puerto Ricans in Spanish Harlem, who famously helped fuse r&b and Afro-Cuban-inspired boogaloo into a special blend of Latin soul—Salsoul, he called it.

But there’s something else at stake in Bear’s approach to genre. Every album, every persona, feels like a ruse. If at first these elements were unwitting, they are now increasingly meta and conceptual, almost Warholian moments of self-awareness and art criticism, canceled out by gestures of “who cares?” On “Who I Am,” for example, the way one plays with musical form is connected to the way one can play with (and lose) their identity. Bear’s voice is mischievously pitched up, as if he took a light sip of helium before laying down vocals:

Kawasaki, slow it down

This might be my brand new sound

Psychedelic, oh, wow

Add an accent to your sound

Now I don’t know who I am

Now I don’t know who I am

Now I don’t know who I am

Now I don’t know who I

It’s a singsong chorus over a bouncy, four-on-the-floor house groove, and also a weighty self-appraisal by an artist who understands full well how identity, like genre, is often a matter of signification. Tempo, dialect, genre—all is mutable, all can be manipulated. Code switching on the dance floor.

Growing up, I often had the sensation that the language in my mouth was not my own. I still have dreams in which there are no words in my mouth. I think this is what led me to become a writer, a doctor of language and literature—power on the page. For this reason, I both appreciate what Bear is doing and sometimes can’t bear to listen. I wonder if there is another musician who is so transparently negotiating and fumbling with the uneven seams of his own ambiguity.

For the past seven years, Bear has been on the West Coast; after a stint in Portland, he now lives in Oakland. The city of Berkeley recently gave him a day in his honor. The chillwave sound has come to represent the clichés of a certain coastal hipsterism (think of Washed Out’s “Feel It All Around,” the theme song to the TV show Portlandia). But the South courses throughout Toro’s discography, especially early on. He has written songs about his missing a lover in Columbia (“Cola”), songs that mention wanting a better life than what was on offer in the South (“No Show”). The title of the album Underneath the Pine—his second, released in 2011—is a reference “to where I want to be buried when I die, which is home in South Carolina,” he has said.

Columbia is not just any corner of the South but one of the most conservative capitals in one of the most conservative states in the country, the city where the first state Secession Convention was held (until smallpox forced it to Charleston). It’s a city known for not dealing with the long shadow of its racist, slave-owning history (the state had the largest percentage of enslaved people out of any state, constituting almost sixty percent of the population in 1860), a city where racial politics tend to be swept under the rug until they can no longer be ignored.

A highway dedicated to a segregationist, the J. Strom Thurmond Freeway, still cuts through the city. Until 2015, the Confederate flag flew at the state capitol, across the street from the Whig, a bar where Toro y Moi once played.

It is a city which, in part, gave the world the quintessential American terrorist Dylann Roof, who was living in Columbia before he opened fire on parishioners in the basement of Emanuel African Methodist Episcopal Church in Charleston, who purchased his gun from a store in West Columbia called Shooter’s Choice. It is a city which, as Rachel Kaadzi Ghansah observed, has a manic sense of race. Roof grew up surrounded by black people; his closest childhood friend, Caleb Brown, was half black. It is a city where black and white neighborhoods have always been nestled alongside one another, as is common in Southern cities where blacks often walked to work in the homes of wealthier, white families.

In interviews, Bear has extolled apolitical virtues like hard work, kindness, decency, education, and nonviolence. But he has shied away from politics. He doesn’t want to get caught picking sides. His most partisan political engagement was, perhaps, a contribution to a compilation of one hundred songs that raised money for causes threatened by the Trump administration. Still, he was careful to note that his contribution, a love song called “Omaha,” wasn’t necessarily about politics, but about “showing support”: “Im [sic] not a political person. I’m not an activist. But I’d like to show my support somehow. Do you think we’re stuck in a system? The more we can educate ourselves on race, sex, and religion the better. Just be decent. Stop the violence.”

Why would a person of color—a celebrity of color—from Columbia be so politically opaque? Particularly in this historical moment. The question mark, again, surfaced. If he is not a political person, what is he?

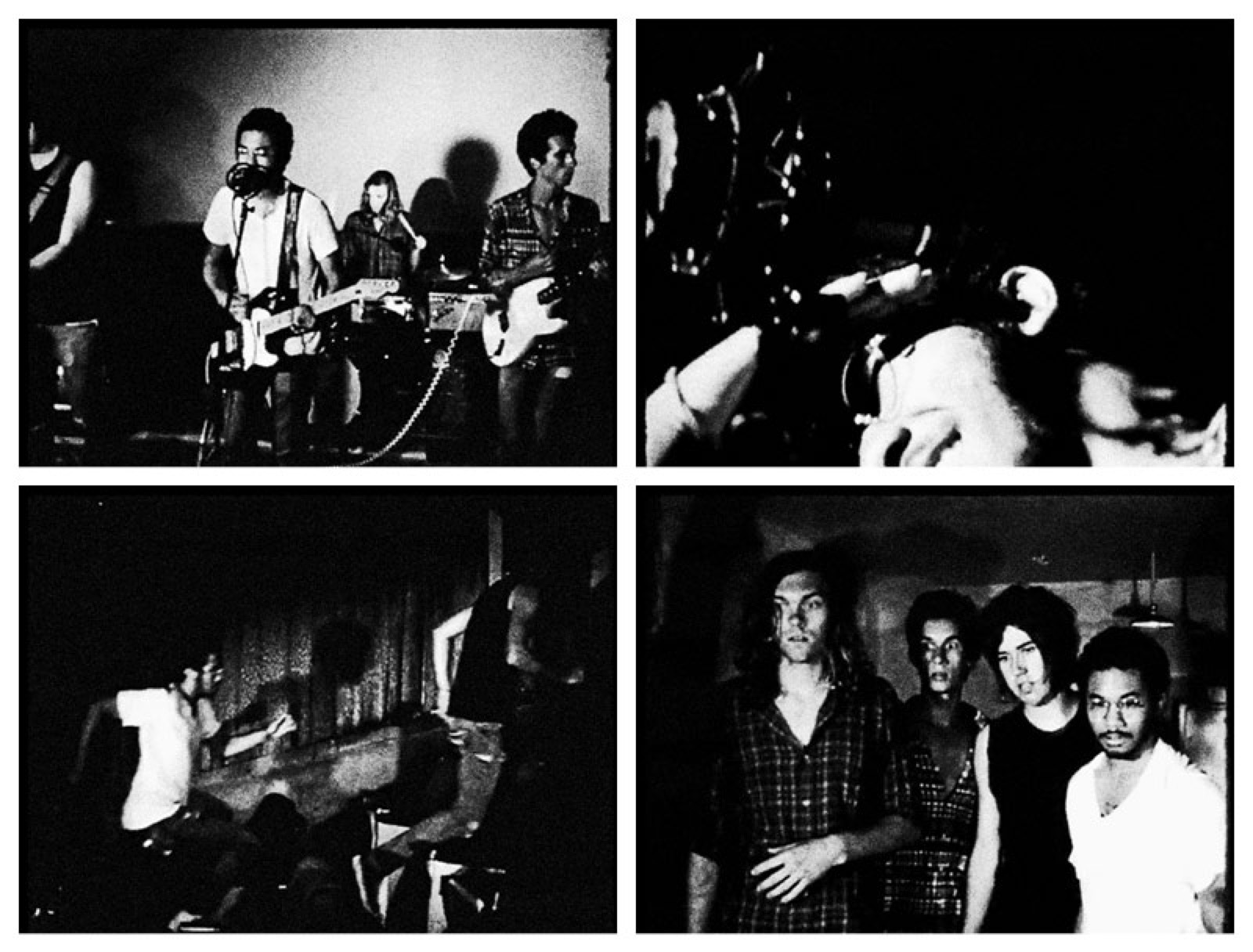

From the music video for “More Control” by the Heist and the Accomplice. Courtesy of Steve Daniels

From the music video for “More Control” by the Heist and the Accomplice. Courtesy of Steve Daniels

“Please stop me if I’m going too fast. There is a lot of ground to cover.”

Mike Jones and I were parked in front of one hundred thirty-nine self-storage units, just past the edge of the University of South Carolina’s campus, beyond a lane of old millhouses, a vestige of the city’s cotton mills, once among the largest in the world. It was a vacant, sepulchral scene, lit up like a football field at night. Until 2009, these storage units, known as the Sheds, were a central organ of the community, a bustling colony of musicians and their practice spaces. Doors flew up to create impromptu courtyards of sound. For a few years, Hootie was here, practicing songs like “Hold My Hand” and “I Only Wanna Be with You” before they landed on the record-shattering 1994 album Cracked Rear View, still one of the biggest-selling records of all time. “It was magical,” said Jones, who at forty-six is a veteran of Columbia’s music scene.

The magic of the Sheds ended when Clif Judy, a cranky neighbor in his seventies, successfully lobbied to have it shut down. “It’s an issue of an old fella getting tired of listening to them, with their tattoos, down there having a good time,” Judy told the Wall Street Journal, noting that his musical tastes tended toward Bach and Christmas music. “I’m relieved the law finally took hold.”

Looking out at the silent storage complex, I turned to Jones and said, “It’s almost like there is a force that is trying to extinguish you.” He leaned in and whispered back, “Exactly.”

You might never know it, but Columbia has some of the same indie heat that fueled nearby college towns like Athens and Chapel Hill. But it’s a few, crucial clicks more conservative, and without a midsize venue, it’s often deemed too small or too out of the way for a tour stop. So the local scene functions largely as a self-enclosed ecosystem; whatever goes down in Columbia rarely makes national waves. The nice way to say it is that bands here have been allowed to progress at their own pace.

Without the right venues, the scene lives in unconventional music spaces often on the verge of closure. One evening in August, Jones showed me several such places. In Five Points, the commercial district adjacent to the university, we ducked into a bar that used to be Rockefella’s—once a legendary music venue where kids moshed to Nirvana before they blew up, now just a larger-than-average college bar with a patio. We cruised past Papa Jazz, the memorabilia-crammed record store known for its exceptionally discerning staff, who are the reason the store has been able to serve Columbia for an improbable forty years (Bear is wearing a Papa Jazz t-shirt in the “Ordinary Pleasure” video). We peered into a skate shop where bands carve out a place to play near a wall of shoes. We drove around the low-rent perimeters of DIY crust-punk venues, where you once could get in for a donated canned good. We walked around Tapp’s, a vast multipurpose arts venue in an old converted department store on Main Street; in September, it was announced

that Tapp’s, too, would have to shut its doors by November.

It’s a fragile, underfunded scene run on scrappiness, resilience, and the enthusiasm of people like Jones, who, with a few interruptions, has worked (read: volunteered) for twenty-six years as a DJ at WUSC, Columbia’s noncommercial, free-format college radio station; for eleven of those years, he has hosted a locally oriented live radio show called The Columbia Beet. Work like this seems particularly noble in a city where the dominant culture is built on the twin altars of male violence: the military and football. Only five miles separate the university from Fort Jackson, one of the biggest training sites for the U.S. Army. It’s a city where weddings are planned around Gamecocks football games, where people walk around with shirts and hats that say COCKS.

In the northeast corner of the city, the Heist and the Accomplice had been training for their own battle, practicing between four to eight hours every Saturday, said Patrick Jeffords, who cofounded the band with Bear. “When we go out and play a show, we’re gonna smoke every band there. I want to be the best band. I had that drive, and still do with Toro as a live thing,” he said. By 2004, Bear and Jeffords had already cut two albums as the Taxi Chaps. With the Heist, the musicianship was becoming more angular, the guitar parts more intricate. Things were blossoming, and early.

Jones was one of the first music professionals to take the Heist and the Accomplice seriously. He had no choice in the matter, he said. “These kids were probably fifteen, sixteen, and they just blew us away.” In 2004, Jones co-produced the Heist and the Accomplice’s first album, as well as an EP in 2005. “They didn’t need a producer, really,” he said. “They knew what they were doing. The songs and performances were already fully formed. No local band I knew came near them in songwriting and professionalism.”

“If you listen to those records, we are all at one hundred, trying to outdo the other one,” said Dylan Lee, who played guitar in the Heist. “Especially live. Crazy, youthful energy and everyone is playing a million notes.”

The final stop on Jones’s tour that day was the radio station. On the way, he stopped to pick up a turkey sandwich for a DJ who had been stuck in the booth by himself. We ascended the stairs to the third floor of a brutalist, mid-century building at the heart of campus, mostly empty on a summer evening. Jones showed me into various rooms; decades of band flyers and radio station stickers were plastered on almost every available surface. He led me into the room of CDs and vinyl that DJs pull from, or at least used to pull from. In the “local” section, he pulled down albums by the Heist and the Accomplice. A breathless review was pasted on the inside of the cover of their debut, Vocals and Orchestrations: “This album may be Columbia’s only hope to be nationally recognized for having something to offer that is not filed in Adult Contemporary or happens to be the latest metal trend.”

I could feel some of the electricity listening to Connections Work, the Heist’s last album, in the car with Chris Wenner, who engineered the album. Wenner is a Columbia native who had returned to South Carolina ready to quit the music business after extended stints in Atlanta and Orlando working at rap and dancehall studios, burnt out by the excesses of the industry. He described meeting Bear, bright and driven, as the moment that pulled him back to his purpose. He hadn’t listened to the music in years and was visibly moved by how good it still sounded. He described feeling a certain sadness; the Heist ended right when it could have taken off.

I asked him why Bear’s vocals were always mixed down to a barely audible level. Bear wanted it that way, he said, although Wenner tried to persuade him to the contrary. In the studio sessions, they would record the band’s instrumentals first. Shy about his voice, Bear would record the vocals later, in private.

Toro y Moi performing at Music Farm Columbia in 2015. Photo by Sean Rayford

Toro y Moi performing at Music Farm Columbia in 2015. Photo by Sean Rayford

When I asked people who knew Bear in Columbia about his character, the remarks tended to fall into two categories.

The first thing most people have to say about Bear is that he works hard. Really hard. None of his friends have ever seen someone who could work so intensely, someone who could write and record songs so quickly, someone who never seemed to stop. His father, a banker, and his mother, a financial advisor, expected him to work hard, and it showed. He came from an upper-middle-class family, but he always had jobs: Chick-fil-A, Wendy’s (“I could run a Wendy’s by myself,” he said), Cartridge World, Carolina Bagel. For a time, he was a graphic design intern for Wes Donehue, now a top Republican political strategist in South Carolina who was lead digital strategist for Marco Rubio’s 2016 presidential campaign (just a gig, Bear’s friends say). Wenner estimates that Bear had written three thousand songs by the time they met, when Bear was in his late teens. Wenner repeated this figure several times during our conversations, as if I needed to hear it a few times to absorb what it meant.

The other thing people say about Bear is that they observe a certain detached and inaccessible quality in him. In Columbia, a lot of people like him, but few seemed to feel like they really knew him, even longtime associates. Bear is described as mysterious, unrelatable. “He’s a social loner,” said Jeffords, who met Bear at age seven, was on his peewee football team (“we sucked”), played with him in the Taxi Chaps and the Heist and the Accomplice, and still plays with him in Toro y Moi. Bear’s socializing mostly revolves around creative production, said Jeffords.

As with any artist, for Bear, being a hardworking loner had tremendous creative benefits. Staying home alone helped him become one of the preeminent bedroom producers of his generation. The rise of Toro y Moi came as the personal computing revolution and affordable (or piratable) software programs like Frooty Loops and Ableton caught up with older, more expensive technologies of drum machines and sampling sequencers. Concurrently, social music-sharing platforms like Myspace collapsed the distance between artist and the public. These were liberating technologies for social loners; the claims that the physical outside world had on one’s reality shrank. Being from the suburbs of Columbia mattered less than it ever did before, and maybe even put one at a competitive advantage.

Bedroom production, in a certain sense, had already been going on for decades. It was an economical workaround for Stephen Paley, in A&R at Columbia Records in the seventies, who moved a 16-track machine into the bedroom of an unmanageable Sly Stone after the label got fed up with paying for missed studio sessions. In the eighties and nineties, artists like Daniel Johnston and Ariel Pink composed on portable cassette recorders. But in the late aughts, the pipeline was suddenly immediate, and happening en masse. To many, Bear was the poster child of the movement. He did interviews, talking about working all day in his house. The Guardian featured Bear in the main image of a 2010 article titled “The Bedroom Artists Who Prefer Creative Solitude.” While the bedroom could breed “music that sounds as personal and as private as Brian Wilson’s secrets,” Tim Jonze wrote, the shift also seemed to result in a certain, almost apolitical, detachment. “How odd that a scene so indebted to the power of the net—the force able to connect the world—is the one that appears most shut off, most anonymous, most likely to be read as a statement of rejection from reality.”

Bear’s development as a bedroom producer accelerated after he met Ernest Greene, who hadn’t yet founded Washed Out. Greene was a graduate student in library sciences at USC. Lee remembered that Greene had a house in Five Points that was a party spot; people used to call him Ernesto. “We started exchanging music, and the next thing you know, we started working on stuff together,” Bear said to Westword. “I guess that’s when we both started getting recognized. That little time we had together definitely helped shape our sounds.”

Bear has said that before he met Greene, he hadn’t used a laptop to record music. He also learned how to sample by watching Greene, a technology that gave Bear the ability to liberate sound from genre. “When you sample music, you don’t hear genre, you hear grooves, you hear music for what it is,” said Bear.

When Toro y Moi found success reaching out to blogs, Bear suggested to Greene that he do the same. Like Toro, Washed Out blew up in the fall of 2009. Greene had been making music under the name for only a month when Pitchfork did its first feature on him. Greene needed to put together a live band for Washed Out, fast. He reached out to Bear, who suggested Dylan Lee and Cameron Gardner from the Heist and the Accomplice. The Heist never came to an end officially, but they haven’t recorded anything since.

Bedroom production was touted as the great equalizer, a shift that wrested power out of the hands of greedy industry honchos and restored it to the hands of the artists. It is easier than ever for people to record, produce, mix, and release their music to the world by themselves. But the shift has also made the music industry more individualistic. As the Heist, the band wrote songs collectively, but as Toro, the creative decisions are mostly Bear’s. “He would often start an album by starting to compile a playlist, and they were the things he was going to listen to to get inspired to make the next record. There wasn’t a lot of discussion about why or who or what. We would get an email suddenly that was the next record, and a date would be set up for us to meet up and practice for two weeks,” said Jordan Blackmon, who co-produced the Heist’s first album and was in Toro from 2011 to 2017, filling miscellaneous roles which included playing instruments, tour managing, driving, keeping books, and selling merch. “That’s something that I’ve always been kind of bummed about working with Chaz is I felt like he did everything solo, and I always thought it would be fun if we ever got the chance to create something together. But that never happened.”

Trying to neaten Bear’s identity into racial compartments doesn’t work. Bear was raised in a white suburban neighborhood and attended a predominantly black high school, where he says he was constantly reminded that he was not black enough. At home, his mom made Filipino foods like pancit and adobo. His African-American father listened to the Clash and Weezer. Cultural dissonance, natural as a pinecone.

“That’s where I come from, which is embracing three different cultures, so it’s hard for me to judge or to side with anything,” Bear told Office. “I still appreciate subculture, and I think that being open minded to all sides of culture is a plus. I’m a bi-racial person of color, who comes from a nice neighborhood, so I have privilege, but then I don’t at the same time.”

If Bear did have a community where he made sense, it was among a group of white skateboarders from the Northeast who were into punk rock and making music (the Northeast refers to the suburbs-esque corner of the city, an area that in the past few decades has been developed with subdivisions and shopping centers). Bear’s skater friends weren’t your average hypermasculine bunch of bros; they were teased and beaten up, called “freaks” and “fags” for skateboarding and wearing skinny jeans. And they were into making music. The coolest guy in the group was Aaron Graves, a pastor’s son with a true sense of Christian benevolence. In the group, Graves was the first to have Pro Tools and a four-track, and it was at Graves’s house that Bear got his first taste of bedroom production.

Graves was known as the baddest skater in the Northeast, which made people fear him until they met him. “I walked out of guitar lessons and saw this kid with a skateboard and long hair buying drum sticks,” wrote Bear on Instagram about the first time he met Graves. “The only thing I could think to ask to break the ice was if he knew the local teen skate legend, Aaron Graves. He simply smiled and replied ‘I am Aaron Graves.’ From that point on, we met up weekly to skate and he essentially taught me everything I know today.”

For his band, Those Lavender Whales, Graves wrote thoughtful and, at times, excruciatingly sensitive songs about wanting his friends to do well and feeling guilt for selfish thoughts, as in “The Arms of a Loving Community Around an Undeserving Individual”:

I don’t mean to hurt anyone’s feelings, but it just seems impossible not to do

I don’t mean to think about things inappropriately, but it just seems impossible not to do

My friends circle ’round each other when one is in need, and they always seem to know what to do

I always hope that one day I can help them out like that, but I never feel quite sure what to do

“And not a drop of that was insincere,” said Lee, who described Graves’s sense of religion as “almost like the way Brian Wilson was like, ‘Goodbye surfing, hello God.’ Or John Coltrane. There’s no reason not to love one another. He was a big influence on all of us. That’s a big reason we never put anyone else down. If someone was impressed by me, I would say, ‘You can do it too.’ That’ll never leave me.”

I got a glimpse of Graves’s sincerity through one of his closest friends, Chris Gardner, Cameron’s brother, who was in Those Lavender Whales with Graves (for a time, the Gardner brothers played alongside one another in Washed Out). We drove to Star Music, where Bear first met Aaron, in an aging strip mall next to a vacated Food Lion and what was formerly Blockbuster Video, evidence of the unforgiving metabolism of the suburbs. We drove to a nearby middle school and parked in front of the benches where they used to skate. Gardner pointed out where Graves had left a sticker that is still there. We sat in the lot and watched skate videos on my iPhone, including one called “Misled Youth,” where they first heard Modest Mouse. We passed through the Summit, a manicured brick-walled housing community with fake waterfalls and cul-de-sacs, pausing in front of Graves’s house. Gardner showed me the neighboring cul-de-sac where Bear’s family once lived. Which house was Bear’s he couldn’t be sure; they all look so similar. We parked in front of Ridge View High School, where Bear and Graves both went to school.

Graves was driven by an underdog ethos, inspired by musical entities that eschewed mainstream success and put their communities first, like Fugazi and Dischord Records in D.C., and especially Elephant 6, the musical collective just down the road in Athens, which gave the world bands he admired like Of Montreal and Neutral Milk Hotel. Along with Blackmon and Gardner, Graves founded the collective Fork & Spoon in the mid-aughts with the intention of pooling their resources to help bring the music of their friends to the world. Fork & Spoon eventually became a record label, issuing twenty releases between 2010 and 2017, including the Heist’s final album and “Sides of Chaz,” a 7-inch by Bear. A vintage website is operational; orders placed on the site are still fulfilled. But the label hasn’t been anyone’s priority for a while, especially since Graves got sick. Graves’s life came to a tragic close in June, when he passed away after a five-year fight with a grade 2 brain tumor.

When I dropped Gardner off at his car, I was jolted back to an alternate reality. It was nighttime at Five Points. Drunk college-age dudes in polo shirts and khakis laughed and yelled at me through the car window. A scene that seems frozen in time.

I’ll never get the chance to speak with Aaron Graves, but I could tell he gave his friends a love that was real and lasting, an example of how to move through the world with a selfless, open heart. I could see how you might think race didn’t matter in indie music, growing up under his wing.

The poet Terrance Hayes grew up twelve miles from downtown Columbia. He attended high school in the Northeast at the same school as Gardner, Spring Valley. In his poem “Root,” Hayes portrays an upbringing full of silences surrounding race:

My parents would have had me believe

there was no such thing as race

there in the wild backyard

Spending time in Columbia, I could sense some of what Hayes described. There were silences and edges that surfaced when I brought up Bear’s ethnicity. Some people said that they didn’t pay attention to it, that it wasn’t a factor in how people treated him. Others responded by saying that race is a touchy subject. There are silences behind these statements that feel like fear. As if by talking about race, you are exaggerating what otherwise might remain invisible.

“I don’t really think that race is an issue when it comes to the indie scene anymore,” Bear told the Huffington Post in 2013. “I notice at my shows that there’s a pretty diverse crowd, and I think the internet helps with that too. People are becoming more comfortable listening to indie rock and hip hop. It’s just a blend of culture now. More people are more unfazed by the issue of a musician’s race.”

After the warm welcome I received from his friends in the Northeast, I can imagine how Bear’s experience might have led him to believe this was true. But there’s also something about this sentiment that feels specific to Columbia. It is a town that has cultivated people of color who have become post-racial icons because, depending on who you are talking to, they’ve either transgressed racial boundaries, or ignored them. There’s former South Carolina governor and Trump cabinet member Nikki Haley, née Nimrata Randhawa, born into a Sikh family, who has suggested that Black Lives Matter is a movement that has “laid waste to Ferguson and Baltimore.” With Hootie, Darius Rucker found success on the wings of frat rock, and later, before Lil Nas X, as the only black person to top the Billboard country charts.

Toro y Moi makes Hootie and the Blowfish seem like civil rights activists. In “Drowning,” from Cracked Rear View, Hootie decried racism and Columbia’s Confederate flag:

Trouble with the world is we’re too busy to think about it, all right

Why is there a rebel flag hanging from the state house walls

Tired of hearin’ this shit about heritage not hate

Time to make the world a better place

By contrast, Bear made further statements diminishing the significance of racism in 2017 in a string of politically toothless tweets:

“We’re all a lil racist. racism isn’t the issue. violence is. stop the violence”

“i feel like us mixed ppl have a better view of the world. we never fit in with anyone.”

“you can only control y o u r perception. i love this world. order requires chaos”

“do good work and be nice.”

After facing immediate backlash, he issued an apology on Twitter (both the tweets and the apology have since been deleted). Jeffords said these tweets shouldn’t be interpreted as all Bear has to say on the topic of racism, because he was high when he wrote them. “He was just really stoned and he thought he was saying some real shit but he was just being stoned and being on Twitter,” said Jeffords. “When I woke up I was like dude, what the fuck, why would you say that? Twitter’s not the place for that. Like sitting on the porch and smoking a joint is a place to say those thoughts out loud so we can all laugh at you, and then you’d be like, oh, that’s kind of dumb.”

I don’t agree with what Bear said, but if I enter the stoned mind, I see where he was coming from. Being mixed, I’ve sometimes felt I had to balance competing racisms, two racist people living inside of me, who are also me, both bigot and marginalized, colonizer and colonized. Navigating this conflict has been the most normal thing in my life, as is the case with many realities we inherit which, in order to live through, we must turn all the way down.

Ahomari Raymond Turner, a Columbia born and bred musician who releases music as blue,girl and CYBERBAE, laughed when they saw Bear’s tweets. “I thought, You are so far removed because you have no idea what you are talking about. Columbia loves him. People only see what they want to. In my world, I remember being handcuffed at like six. A policeman came to my bus stop before school,” said Turner, who is black, queer, and gender nonconforming.

“It is weird, because he is black and Filipino,” said Turner of Bear. “I don’t know him personally. I don’t know what he was trying to convey. I have a friend who grew up in the suburbs and they think like that. I grew up in a predominantly black neighborhood. Police knew my neighborhood by heart. I have nothing against Chaz or Toro y Moi, but that sounds like something someone would say who grew up with privilege. It just shows you can grow up in privilege and be black and have no grasp on what is happening. I think the music he makes is great. What he did was smart. Get up out of here.”

In the past, Turner has spoken out about racism in the indie scene—racist bar owners, how hard it is to get opportunities in Columbia (where there’s “no faith in black artists”), how they have to go to the other side of town to see an r&b show. But since they’ve spoken out on these topics, Turner has been accused of being mean. The inability to speak openly has left them feeling isolated. “I try my best to keep my mouth closed and do what I need to do for myself. I’m pretty much a recluse these days, because I don’t want to deal with Columbia. You just can’t talk about things.”

Preach Jacobs, a writer and rapper, is far from a recluse; he writes a column on hip-hop and politics for the Free Times, works at Papa Jazz, and once ran for city council. But, like Turner, he has also encountered backlash from talking about race in Columbia, though it hasn’t stopped him. When his column comes out, the trolling is so bad that he told his job not to send him any mail responding to his articles, good or bad. “People have to understand you can have conversations about race without calling somebody a racist,” he said.

In August, I went out to dinner with Jacobs, Wenner, and the producer Chris Charles. We’d come from Wenner’s studio, Seaboard Recordings, where Jacobs was laying down vocals for a new track. (Bear had been there a few months earlier working on some songs when he was in town.) We were talking about musical intelligence in the digital era and how it coincides with a world where categories of race and genre seem harder to discern. Wenner suggested that Bear’s music reflects the musical IQ of his generation; with one hundred years of prerecorded music online, you don’t even have to go crate-digging—it’s all on YouTube. People have access to a broader musical palette than ever.

“He wants to make music that, when you take the cotton swab, put it in your mouth, and send it to Ancestry.com, and it comes back all these genres,” said Jacobs.

It sounds like melting-pot music, I said, for better and for worse. With all of Bear’s shifting personas, I said, I wonder who he is at his core. Who he is, down to his roots.

“I think that’s why his albums sound so different,” said Jacobs, “because he’s trying to figure that shit out.”

I am playing the role of curious journalist. Maybe Bear doesn’t know himself. His ability to master musical codes reflects his cultural multiplicity, and also a sort of digital intelligence, not unrelated to the era of algorithm, predictive outcomes, and creativity based on the swift, automatic recognition and mastery of form. I catch myself thinking outside of my body, sliding into theory. Of talking about someone as if I weren’t actually talking about myself. But that would be cynical—no, hypocritical.

In college, I studied Latin, Ancient Greek, French, and German. In graduate school, I wrote essays about how the poetry of Ovid and Catullus emerged centuries later in Chaucer and Shakespeare. For my doctoral dissertation, I wrote a bilingual, transnational study about how the literature of William Faulkner and Richard Wright surfaced in philosophy and film in France and Algeria. I sought connections everywhere. My own mixture didn’t seem worth studying. In fact, I was offended when professors encouraged me to work in Asian-American studies. It was such a cliché for academics of color to study themselves. Why did people assume autobiography was the only thing nonwhite people were capable of? I valued philosophical questions of being, but wrote off what I am as an inferior, somehow easier question.

In June, I went to the Philippines for the first time. It was a trip I had put off for many years. I had a block around going there, which became almost embarrassing as the years ticked on. For decades, my mom hadn’t gone back. The stories that I had heard about her youth described a person I didn’t know, a person she had in some ways sought to shield me from. She had grown up sleeping in a crib until she started kindergarten, then graduated to sleep in a military-style cot, which she shared with her brother. My aunt described having to use safety pins to expand underpants that she had grown out of because they couldn’t afford new ones. But the mother I grew up with did everything she could to make us look like we didn’t come from that.

I grew up in a predominantly white neighborhood in Seattle. I went to schools that were diverse, but divided along racial lines. I had mostly white friends. Glomming on to groups that didn’t look like me felt both inevitable and natural. But it also felt like a betrayal, like I was constantly cooking some sort of lie about who I really was, a lie that felt like it never quite worked. I, too, identify with the label of social loner.

It has taken time for me to directly address what has stitched me together and I’m constantly revising the story. It’s much harder to think through these things in public.

Every musician coming out of Columbia faces an uphill battle. But talking to Turner reminded me of the musicians who don’t find favor with white club owners, the ones who don’t have white backing bands or communities with the resources to push them onto the road, the ones who couldn’t move back in with their families while they got it together to make a next move. It’s not that Bear shouldn’t perform his racial identity the way he chooses. But to minimize racism creates the illusion that things don’t need to change. It shows he’s not in tune with the struggles of great musicians who truly live on the margins, who can’t stick and move like he can, who can’t play his game. I hope that Turner doesn’t stay a recluse.

Throughout the summer, Bear declined multiple interview requests, although he was aware of the contours of my reporting in Columbia through his friends I’d been speaking with. If I could have spoken with him, I’d have asked what he was searching for when he was writing thousands of songs as a teenager. I’d ask how he feels like a racist. I’d ask, Why didn’t you own that shit you tweeted and explain where it comes from? I’d ask what he had figured out, and what he had yet to fully understand about himself. Maybe I’d have tried to compare notes about our mothers, who both came over from the Philippines when they were in college. I’d tell him about my trip there and what it had revealed to me.

At the end of August, a couple weeks after my final visit to Columbia, I finally got to see Bear, although it was still from a distance. It was at Afropunk in Brooklyn, the annual sprawling blur of melanin and music, mesh and pasties, fashionistas and corporate sponsors. You’d have to be blind not to see the stunning celebration of Black difference, freedom in the visual and sonic articulation of identity, the monumental potential of Black economic power. Yet the event was muddied by corporate charade, the sort of sponsored, woke-branded content and influencer culture that felt the very opposite of freedom. Instagram had sponsored an elaborate photo booth; the Black selfie is a treasured commodity. Progress? Another line from Hayes, a truth as potent as the spectacle before me: Never mistake what it is for what it looks like.

On the afternoon of the second day, I found space on the grass near the front, just in time for Toro’s set. The announcer thanked Target for sponsoring the festival’s air-conditioned hair and beauty village. Earlier that week, Bear had released his latest project, smartbeats, an ambient EP sponsored by the single-use plastic bottled water company SmartWater. (“When I first heard the idea of smartbeats, I thought it was a really conscious decision to sort of make that leap towards wellness,” Bear says in an ad for the Coca-Cola–owned company, drenched in double-speak.)

Joints sparked as Bear, newly blond, and his band took the stage. They hailed from South Carolina, California, he announced.

“If I go onstage or go to a show, I like to reference more of the psychedelia, bohemian vibes, mixed with a little bit of raver,” Bear was quoted in an recent advertorial for AG Jeans. At Afropunk, he was doing just that, wearing paint-splattered pants and a tie-dyed Ram Dass shirt with the slogan becoming nobody. The self, obliterated. There was something existentially accurate about it.

The band performed well, sounding like the recorded version. There was perfection in Bear’s delivery, even in the ad-libs and the dancing. After playing “Who I Am,” he told the crowd, “That song is about not knowing who you are. You know who you are.”

When he performed “Ordinary Pleasure,” a bouncy single off of Outer Peace, something really started to grate:

Maximize all the pleasure, even with all this weather

Nothing can make it better

All this weather. I thought of the water bottles. The climate crisis. ICE.

Nothing can make it better

Maximize all the pleasure

I have tried to live through this music and have found something deeply familiar, and unsettling. I’ve thought of my own lust for maximal pleasure and refuge in the face of internal dissonance, global catastrophe, the living hell of Trump’s America. I was reminded of the sanctuary of my own adolescent half-breed bedroom, and the ways I live in it still.

Could anyone else hear it? I looked around. To my left was a woman in a bucket hat fashioned out of a blue Ikea bag. To my right was a woman wearing miniature functionless eyeglasses gyrating in a cloud of weed smoke.

Bear neatly brought the concert to a close, announcing that there were two songs left, and then one. Before leaving the stage, he raised a fist into the air.

“Fight the power,” he said, then pitched three Dasani water bottles to the crowd.

Enjoy this story? Subscribe to the Oxford American.