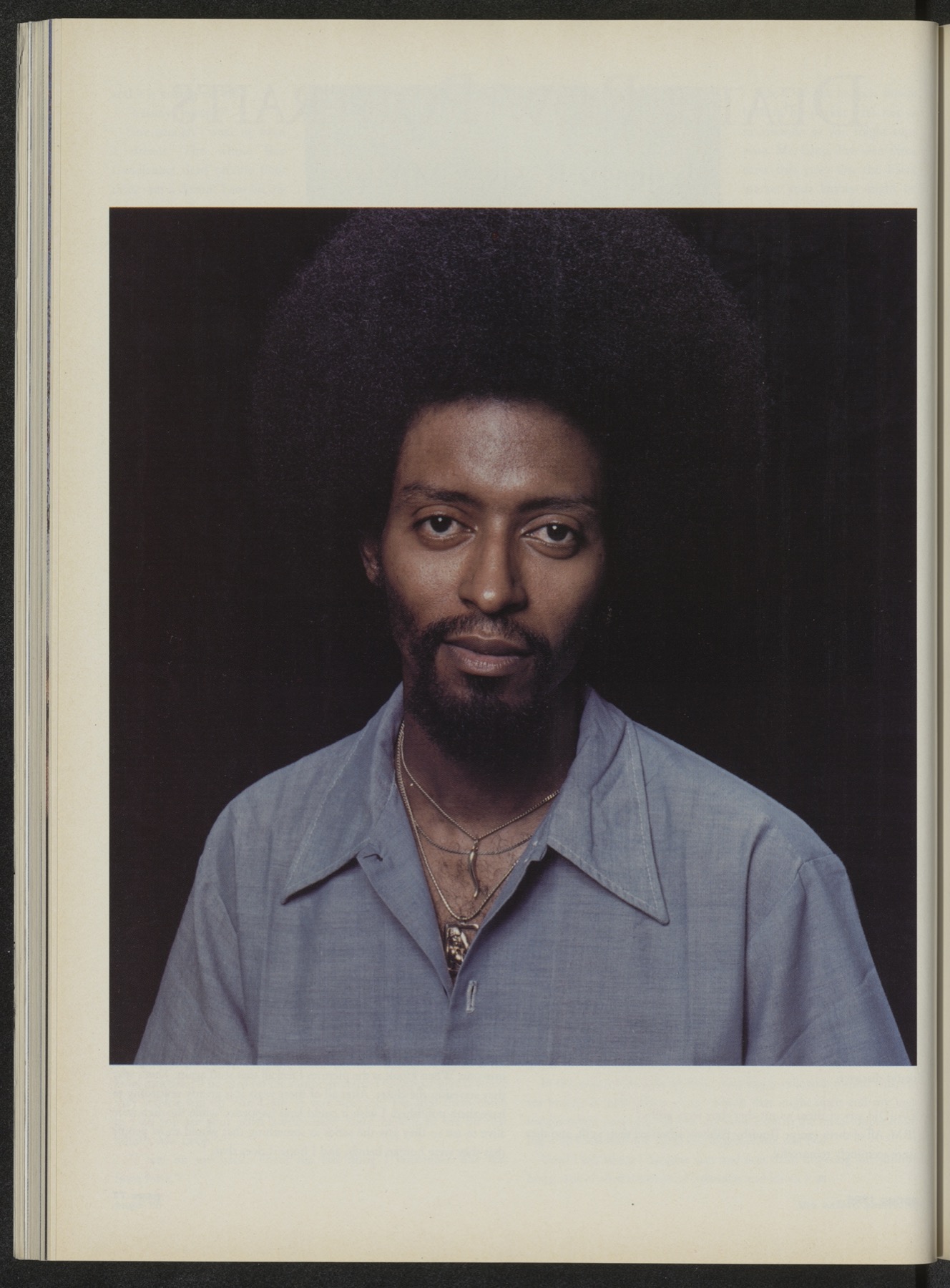

Death Row Portraits

By John Ramsey Miller

In 1982, John Ramsey Miller was granted permission to take portraits of death row inmates at the Louisiana State Penitentiary at Angola. The photographs were scheduled to appear in Life magazine but at the last minute the publisher pulled them.

They are shown publicly, for the first time, on the following twelve pages.

Mr. Miller allowed The OA to ask him a few questions about the project.

THE OXFORD AMERICAN: How did you first get the idea to make portraits of death row inmates?

JOHN RAMSEY MILLER: I had a friend with Amnesty International and we were talking about the death penalty one night. I said I was for it. He said if I knew those people I couldn’t be like that, and I told him that was bullshit. About a week later on tv I saw Colin Clark [a convicted murderer]. He was daring the state to execute him. He said either execute him or let him go. I thought it would be an interesting group of photographs.

OA: Was it difficult to get permission to take these photographs?

JRM: It was the most challenging and frustrating experience I had ever encountered. I had to get permission from each inmate, their attorneys, and then after that fight and numerous meetings and phone calls, I ran head-on into the Louisiana Department of Corrections. The permissions phase lasted over a year. I kept calling and calling and I guess they figured I’d never go away, so they relented.

OA: Why do you think the inmates agreed to do it?

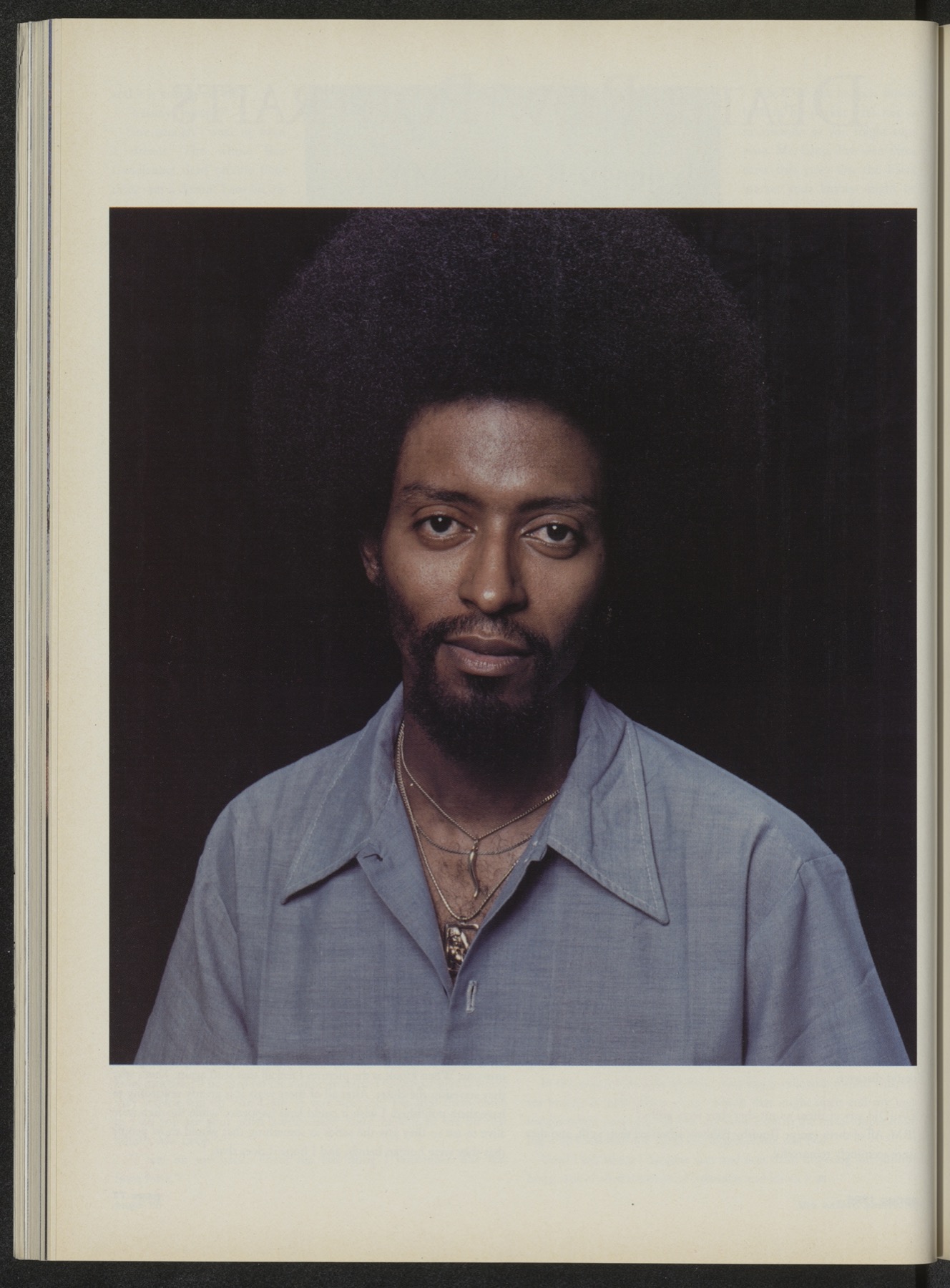

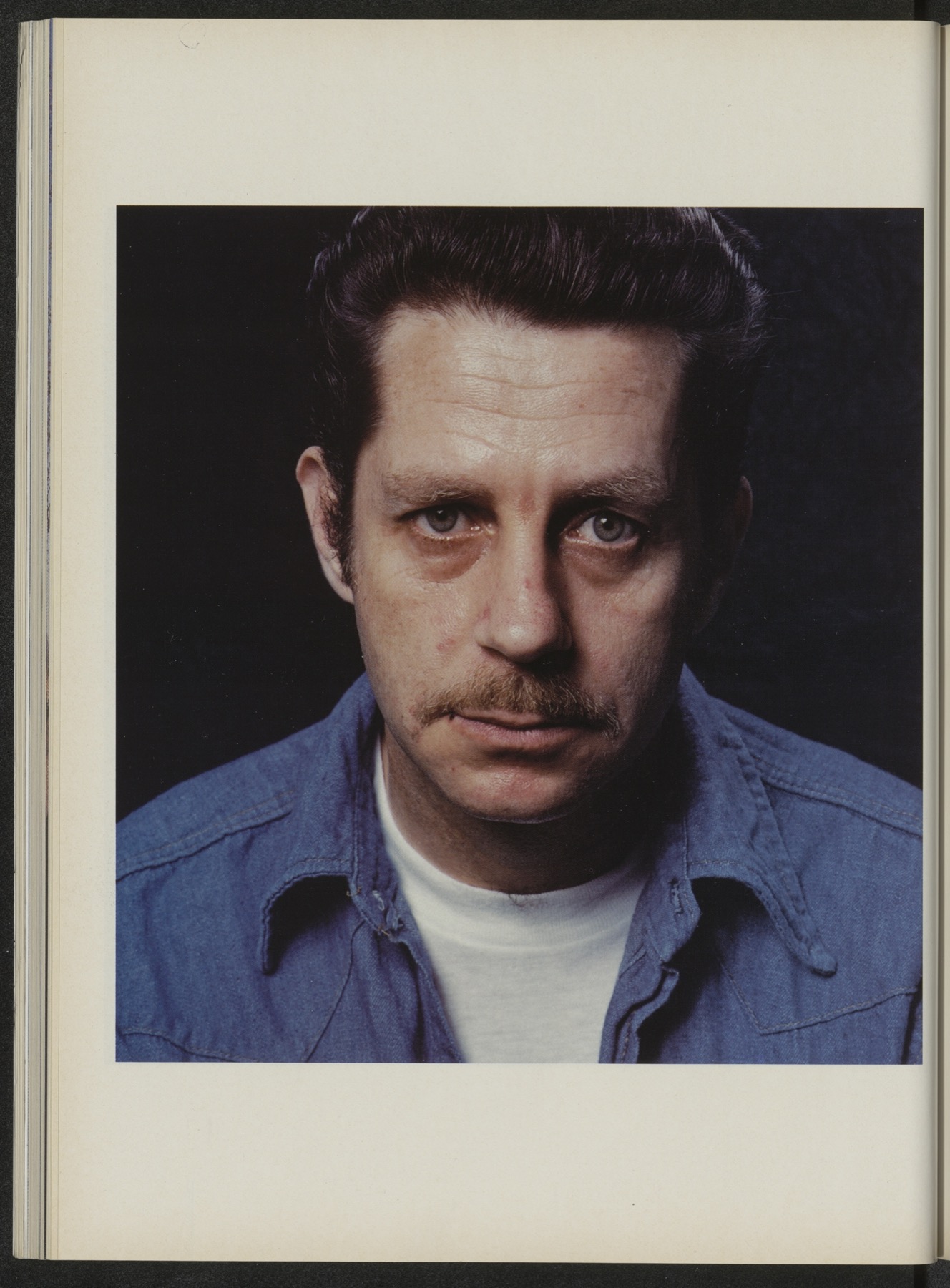

JRM: Their motivation was twofold. They wanted the world to see them as individuals, vulnerable human beings who had made a mistake, and rush to save them from impending death. Secondly, they wanted decent pictures of themselves for their loved ones.

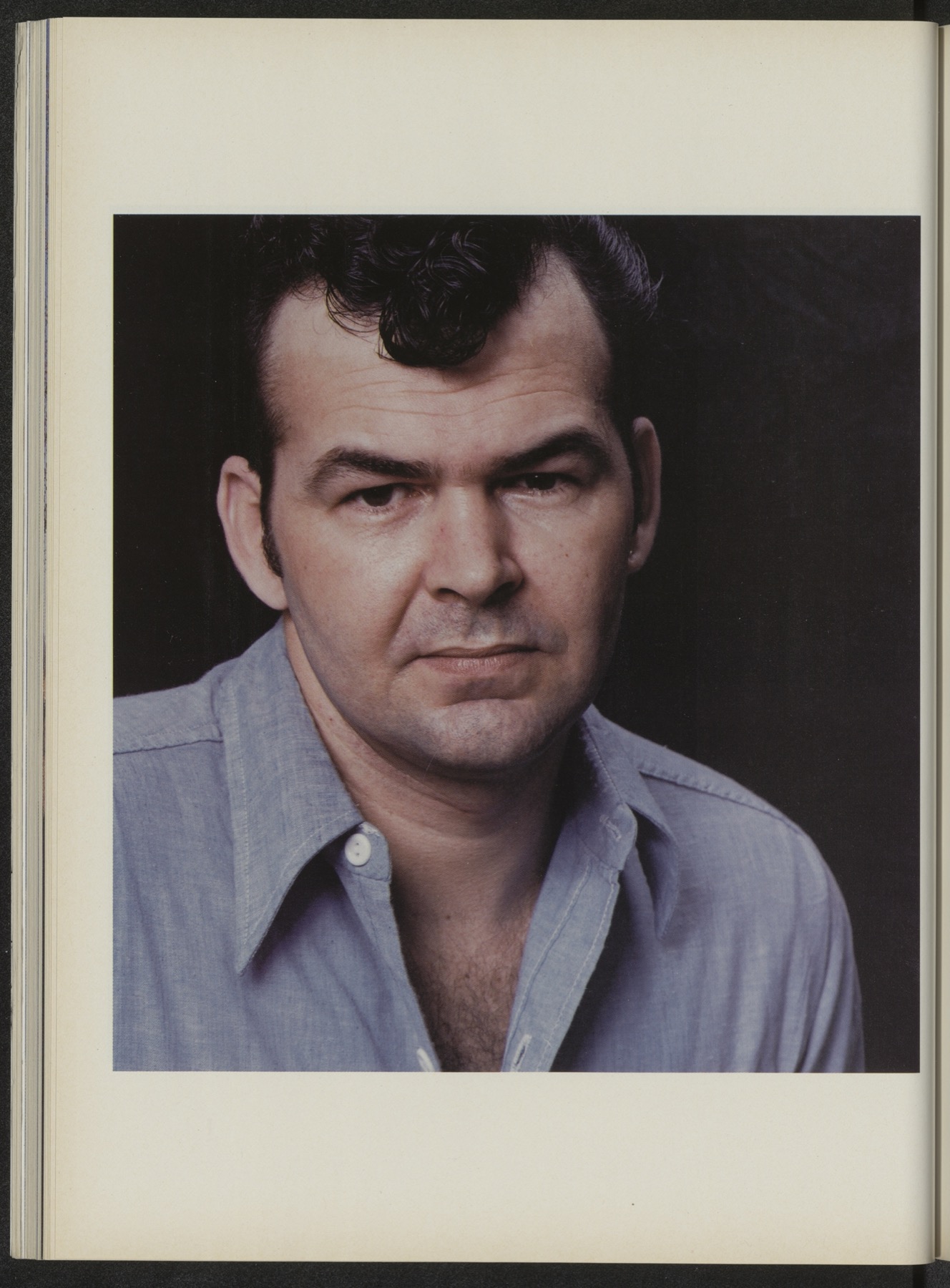

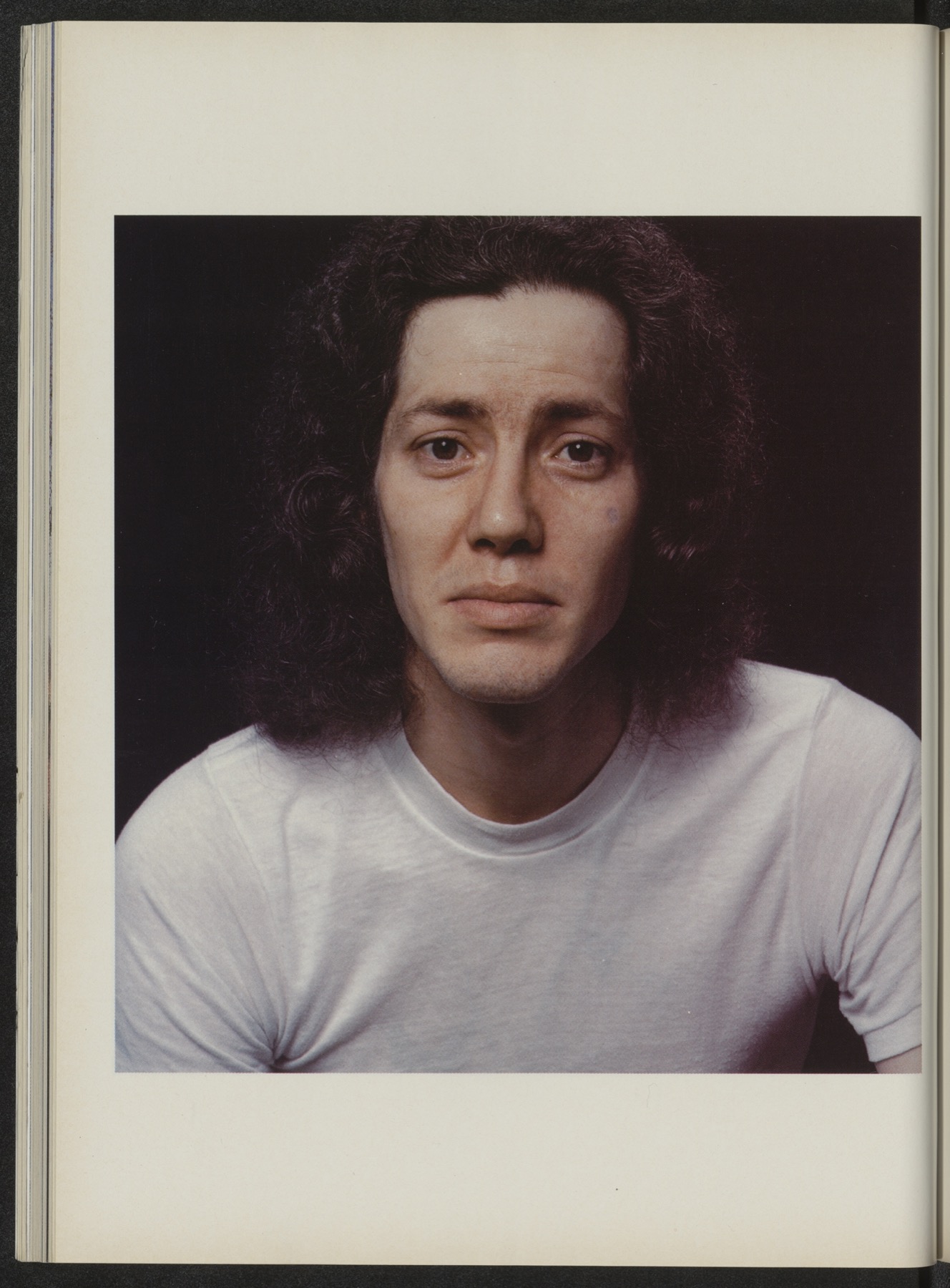

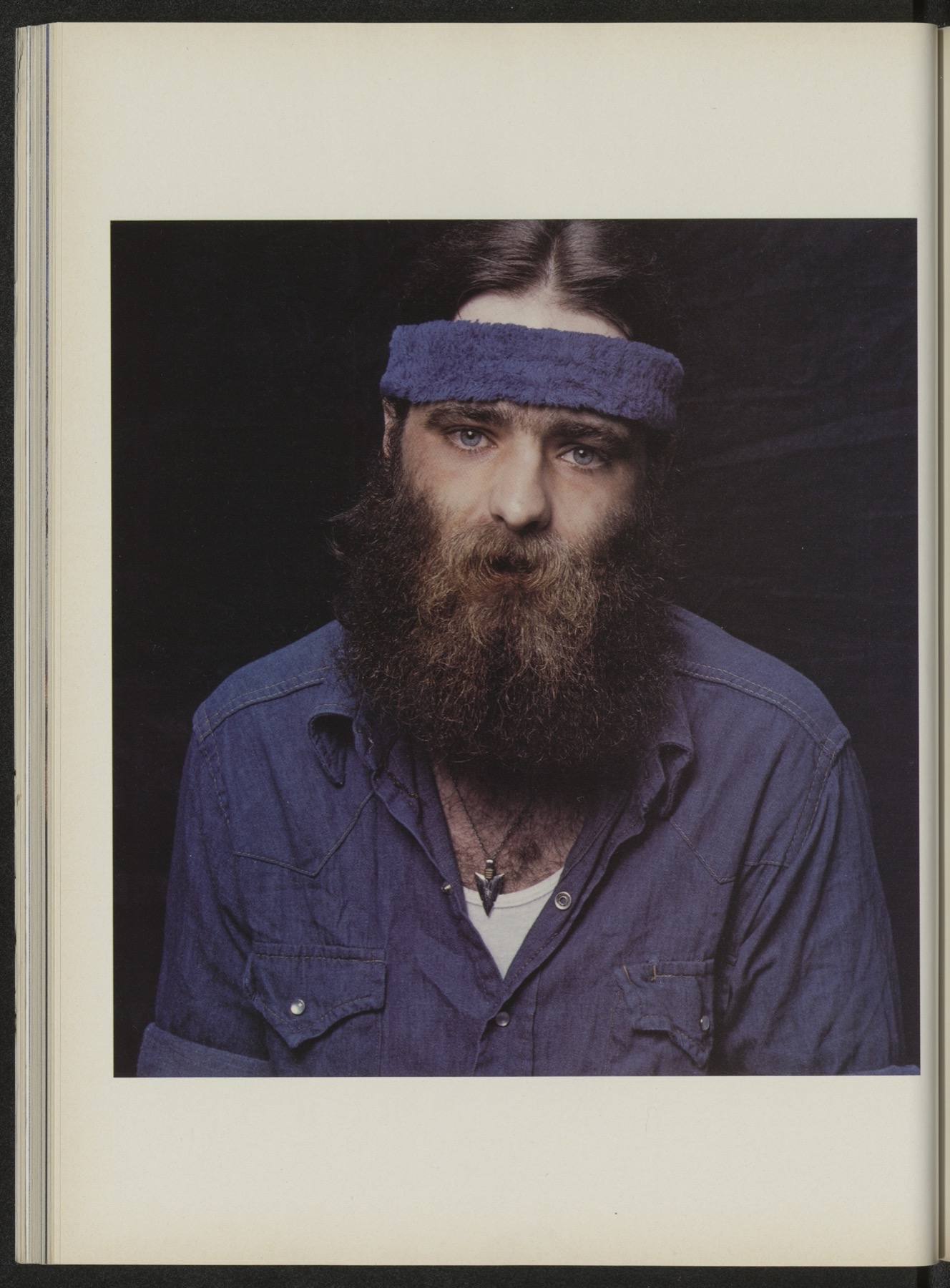

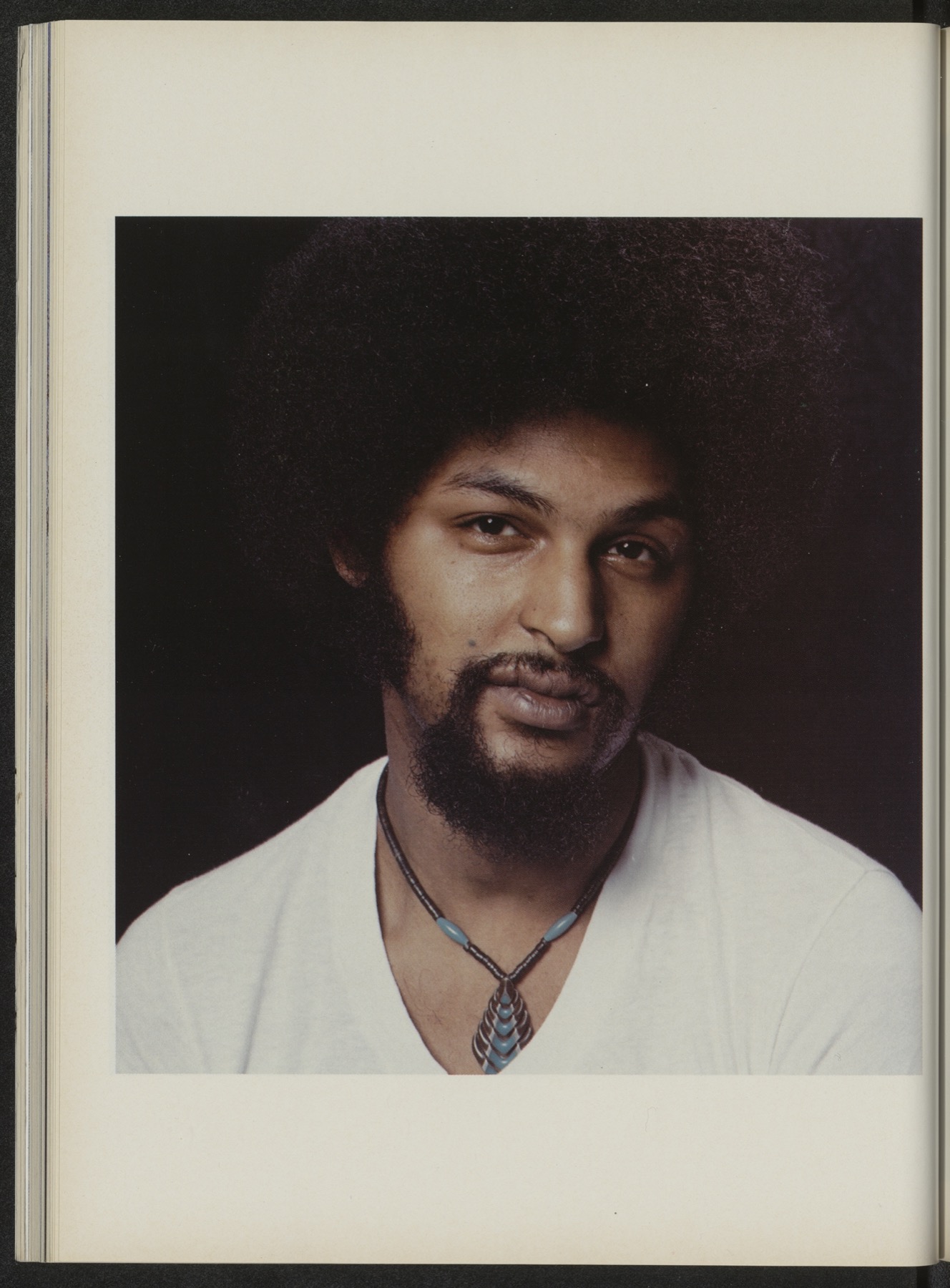

OA: What aspect of these men did you try to capture?

JRM: I was interested in the faces their mothers had seen, faces we could never see on the news or in the papers. If you look at the pictures you can tell that their eyes look just like yours and mine. No difference that I could discover.

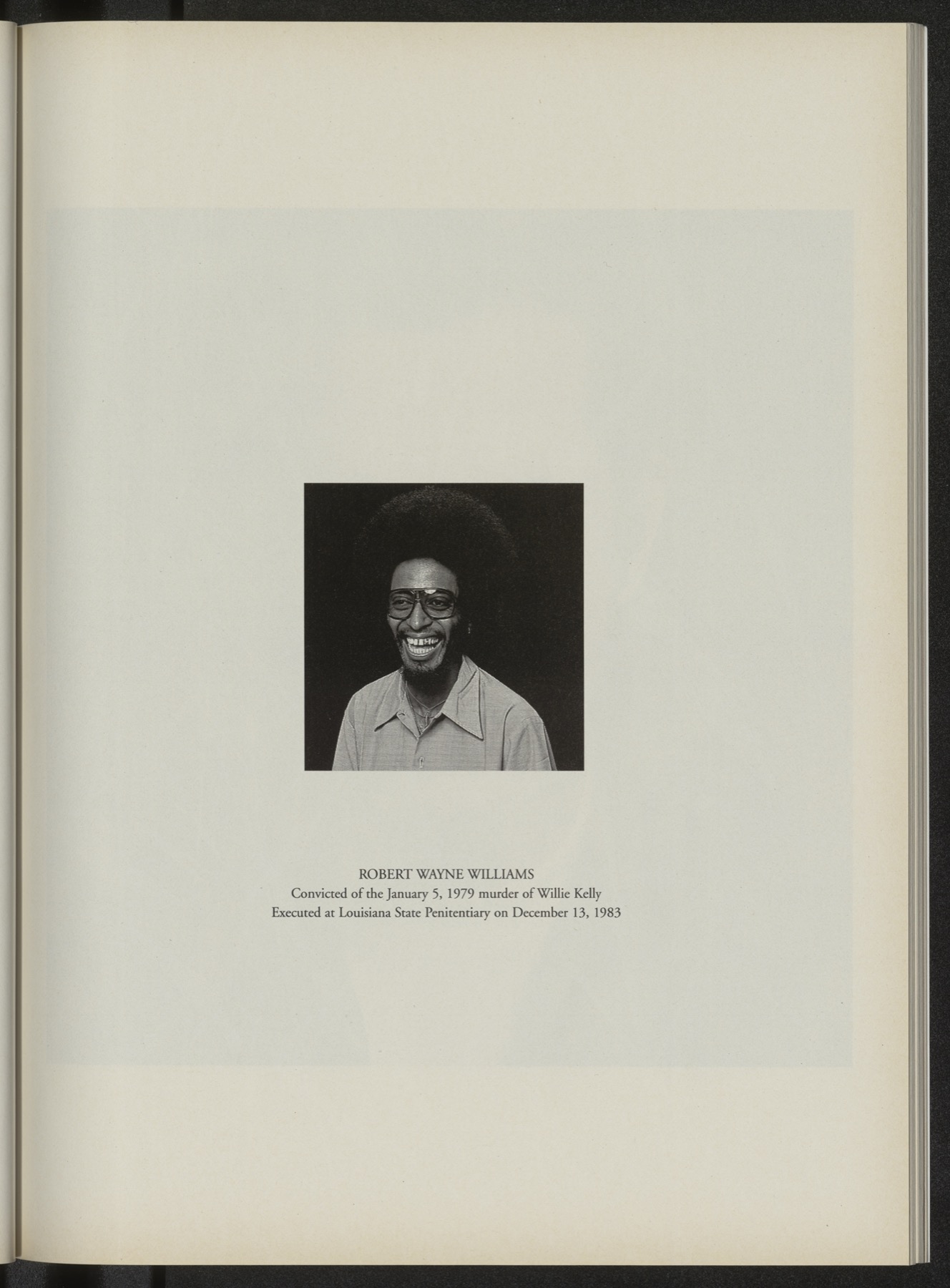

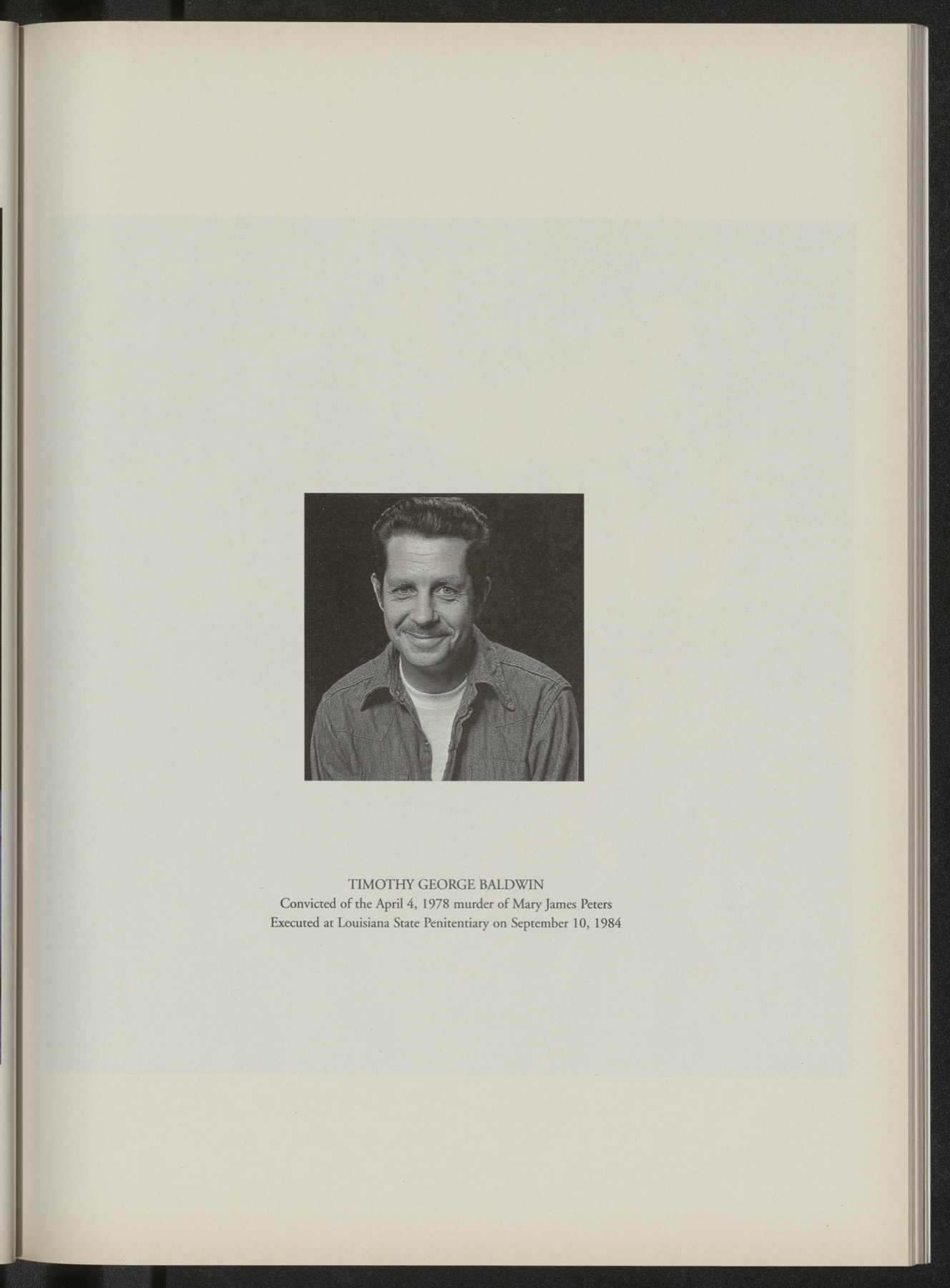

OA: Did any of them admit that they were guilty?

JRM: All of them except Timothy Baldwin admitted their guilt, and they were seemingly remorseful.

OA: What makes you say seemingly remorseful?

JRM: Well, you can’t tell. Ever. In the letters they always said they shouldn’t have done what they did but they would then say that nobody should do what was being done to them. It was always turned around, they seemed to think that what was happening to them was worse than anything they could have done.

OA: How did you make them smile for the photographs?

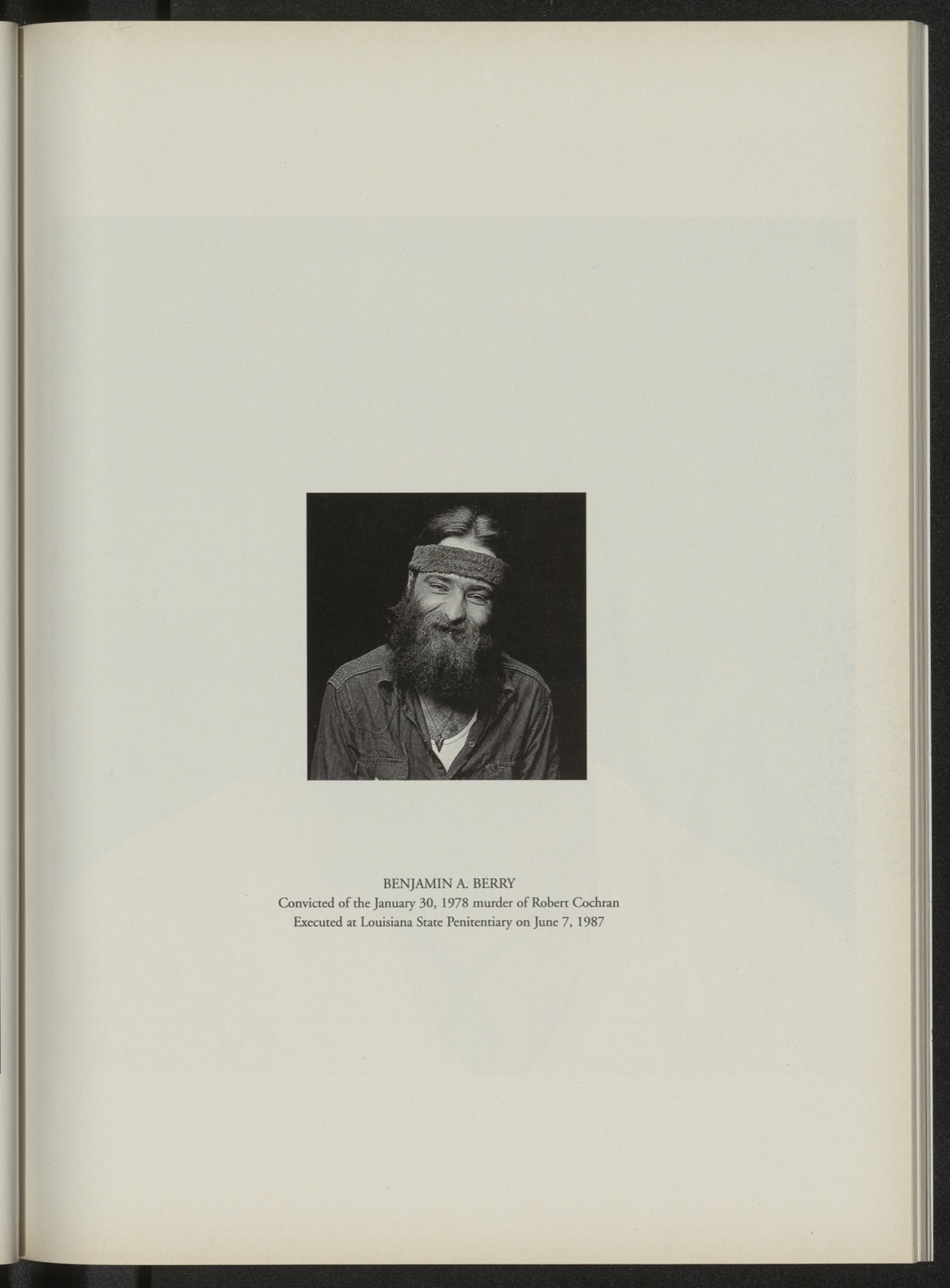

JRM: Just by talking and telling jokes. They’d tell me one and I’d tell them one. They were nervous at first, especially Timothy Baldwin, but once they relaxed it was pretty easy. Benjamin Berry didn’t want to be photographed smiling at all. I cracked him up with something I said, I can’t remember now what it was. I think he thought he looked foolish when he smiled.

OA: Did you develop friendships with any of these men?

JRM: No, I kept it at arm’s length. I didn’t want to be friends with them. I didn’t want them to depend on me and I didn’t want to depend on them for anything. Friendship is a thing that works on a very deep level—you can’t be their friend without getting involved. It was a cop-out on my part.

OA: What do you think of when you look at these pictures, fourteen years after they were taken?

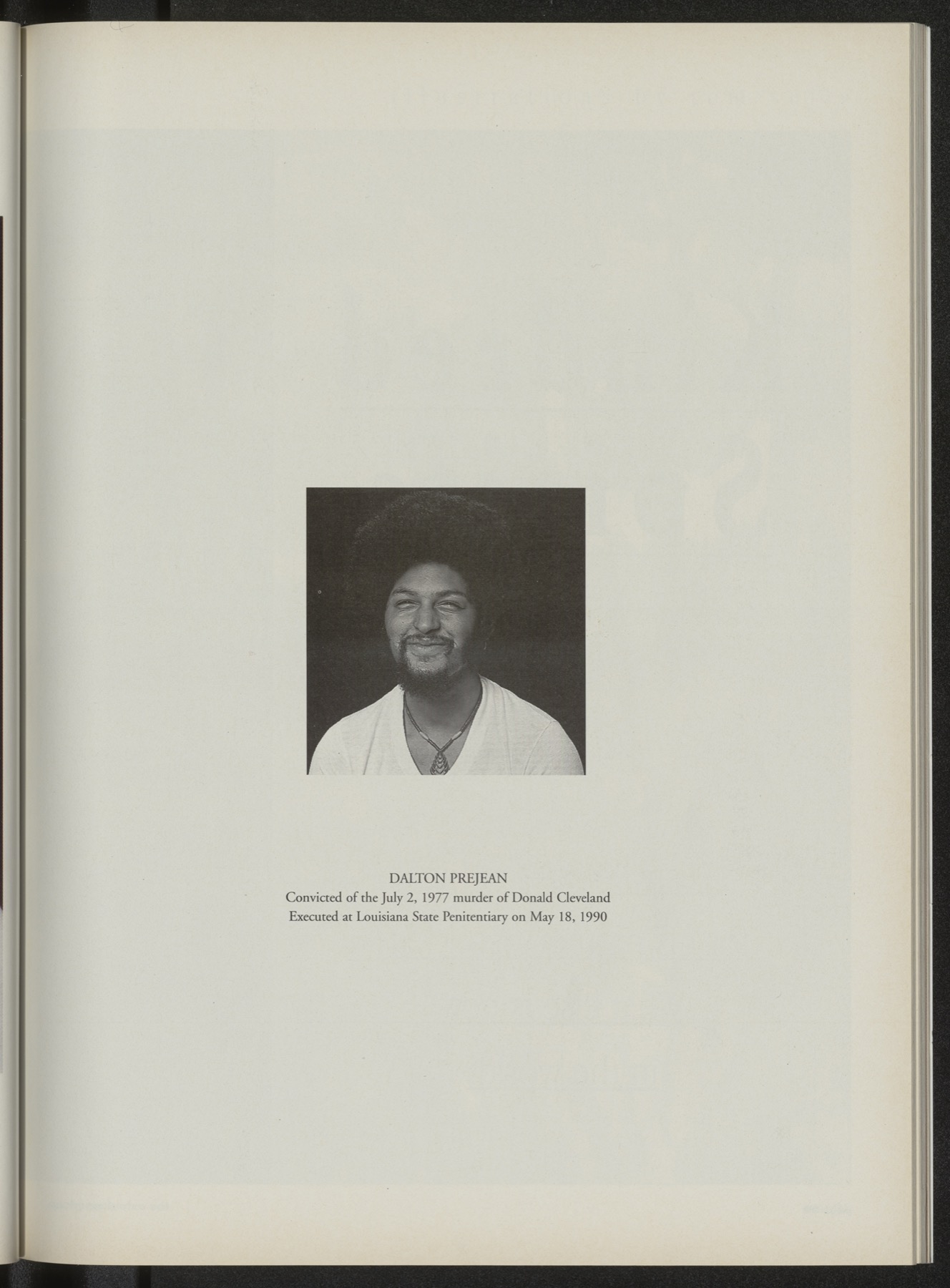

JRM: When I look at the pictures I see them like a film in my head, them sitting in the chair, grooming themselves to have the photographs made. It’s still painful. I remember the whole experience—the frustration and the anger and the futility of trying to deal with the system is all rolled up into one. When I look at the pictures I feel all that stuff again. That’s why they stayed in the closet. After all of these years it is greatly rewarding to have them published. I wish it could have happened while the men were alive to see it; they saw the series as something that would show people that they were human beings, and I hope it does that.