R.E.M. for the People

By Elizabeth Wurtzel

Illustration by Mike Reddy

Editor's note: This story first appeared in Oxford American's third issue in 1993. It was reprinted in 2020 for the Greatest Hits Issue, which was guest edited by Brittany Howard and compiled some of the most beloved music writing from our archive.

When I was in college in Massachusetts in the late eighties, what I remember most about the early spring-fever days was the way the dorm-room windows would be flung open to reveal that the student body seemed to be listening to one band and one band only: R.E.M. Indeed, you could walk across the budding grass on the campus green and hear one R.E.M. album blasting out of a building on the right side—say, the opening chords of “Radio Free Europe” from Murmur—and hear a different R.E.M. song—maybe the exuberant “Exhuming McCarthy” off Document—coming from somewhere off the left.

Now, mind you, I attended one of those northeastern schools-with-attitude where the political consciousness and intellectual pretentiousness of R.E.M. would seem to fit in well with the mood of the times—this was back when people were building shanties in the middle of the main quad to protest South African apartheid—so the band’s popularity was hardly surprising. But, amazingly, R.E.M. had sizable followings at all sorts of schools, even at southern campuses where Reagan Youth drove BMWs, where sorority girls and homecoming queens ruled the social scene, and business-majors with country-club backgrounds would be prone, if they didn’t know these guys were rock stars, to spit on the members of R.E.M. for looking like hippie trash. By sometime in the middle eighties, R.E.M. found themselves occupying that strange rock & roll realm where they were idolized by people who, in real life, would never have invited them to rush their fraternities. The sad rule for most of us is that our reach almost always exceeds our grasp, but R.E.M. was grasping and holding onto an awful lot more than they were reaching for.

The point is, for most people R.E.M. had their breakthrough success two years ago when Out of Time, their seventh album (not counting the collected b-sides on Dead Letter Office or the anthology called Eponymous), made it to #1 on the Billboard charts. But to me, the band was successful beyond the point of no return when the girl who lived next door to me my freshman year, someone called Libby who hailed from Greenwich, Connecticut, declared R.E.M. to be her favorite band on earth and played her collection nonstop. With just a wall to separate us I got it all—a steady diet of Murmur before breakfast, Reckoning at dinnertime and Fables of the Reconstruction late into the night. Since that could make even the meekest among us long for some Black Sabbath, there hardly seemed to be any reason to get into the band myself. Long before any R.E.M. albums went gold or platinum, the band’s omnipresence on the college scene made them as much an oppressive force in bookworm circles as the “mainstream” music they were supposed to be an “alternative” from was to the rest of the world.

Listening to R.E.M. also seemed to be a first step toward declaring yourself a member of some strange special interest group, or becoming a category in some marketing expert’s demographic study that would re- port that you, say, bought clothes at the Gap, drove a solar-powered car, lived in Seattle or Santa Fe, ate Terra Chips, drank Rolling Rock, subscribed to the Utne Reader, and would be likely to purchase reusable diapers once you started having babies. Or something like that. All this is to say that R.E.M.’s music became popular about the same time that a standardized, commercial notion of an alternative lifestyle was developed, so that all the bric-a-brac and bohemian touches that college students invented for themselves, and thought were just theirs, actually became something that could be bought at a shopping mall anywhere in America. For me, it was a sorry enough thing that without even trying I: had paisley-patterned tapestries on my ceilings and walls, took courses in post-structuralist literary theory, spent afternoons attending Eric Rohmer double features at the nearby revival house, tended to date men with long hair who wanted to be filmmakers—all of this was stereotypical enough without adding the R.E.M. imperative into the picture. Better to listen to Bruce Springsteen and be thought of as a mall-rat from New Jersey (then again, that amounts to slumming, a whole other cliché) than fall any deeper into earthy-crunchy collegiate reverie. And just as an alternative lifestyle began to pick up steam as a statement that could be exploited commercially (hence, you were suddenly able to buy jeans with holes already punctured in the knees, or to purchase fishnet stockings with runs already snagged up the sides), if you follow the trajectory of R.E.M.’s career, you can map out the development of college radio from a minor and mostly ignored student endeavor to an actual growth industry. Because R.E.M. became rock stars via the support of college stations, record companies suddenly realized that promoting at the university level was a marketing technique worth trying. Student disc jockeys tend to be passionate about music, they’re willing to talk up new bands that they’re hot for, and they’re an excellent tool for creating a band’s buzz. Their audience may be small, but if you get all the college radio listeners together, you’ve got a groundswell—enough people to get an album on the charts. R.E.M. had built itself up to multi-platinum status through gradual and incremental growth, and had maintained a base of deeply loyal fans throughout, mainly because their following began at the grass roots. Using R.E.M. as a model, record labels realized the importance of artist development and slow growth. They realized that the big hype might sell a million albums once but it won’t build a band for a long-term career.

It seems reasonable to say, then, that R.E.M.’s success taught some record labels a few honorable lessons. But it also skewed the term “alternative” to define a new branch of commercial music with its own set of standards and indicators that defied the norm to create a norm of its own—usually, anything that might be described as “quirky” or “abrasive” or both could qualify. While alternative music had always happened by accident—a band would discover somewhere along the way that they just didn’t fit into any pre-existing categories—suddenly “alternative” itself became an anti-category category: record labels set up alternative departments, and even bands that have become utterly mainstream—like R.E.M. and U2—can still be found on the alternative charts. Because of R.E.M., the oddball music that used to just barely subsist on the margins of pop music culture is now marketed as aggressively, and expected to sell just as well, as Michael Bolton.

All of this would be fine, except that what works for R.E.M. is not likely to work for most other “alternative” bands. Despite some strange notion developed somewhere out there that R.E.M. is offbeat and different, in truth the band has always created a jingle-jangle guitar-based prettiness that is simultaneously sweet and edgy, mixing the lush Rickenbacker folk-rock of the Byrds with the dark, dour alienation of the Velvet Underground to produce music that is really quite catchy. Playing off a guitar arpeggio and staccato drum beats that make a song sad and boppy at once is a really great idea—but it’s not one that is difficult for an audience to grasp. In fact, one of the most enjoyable aspects of R.E.M. is that the music combines so many pre-existing elements of the musical vocabulary that it’s always instantly familiar and easily digestible.

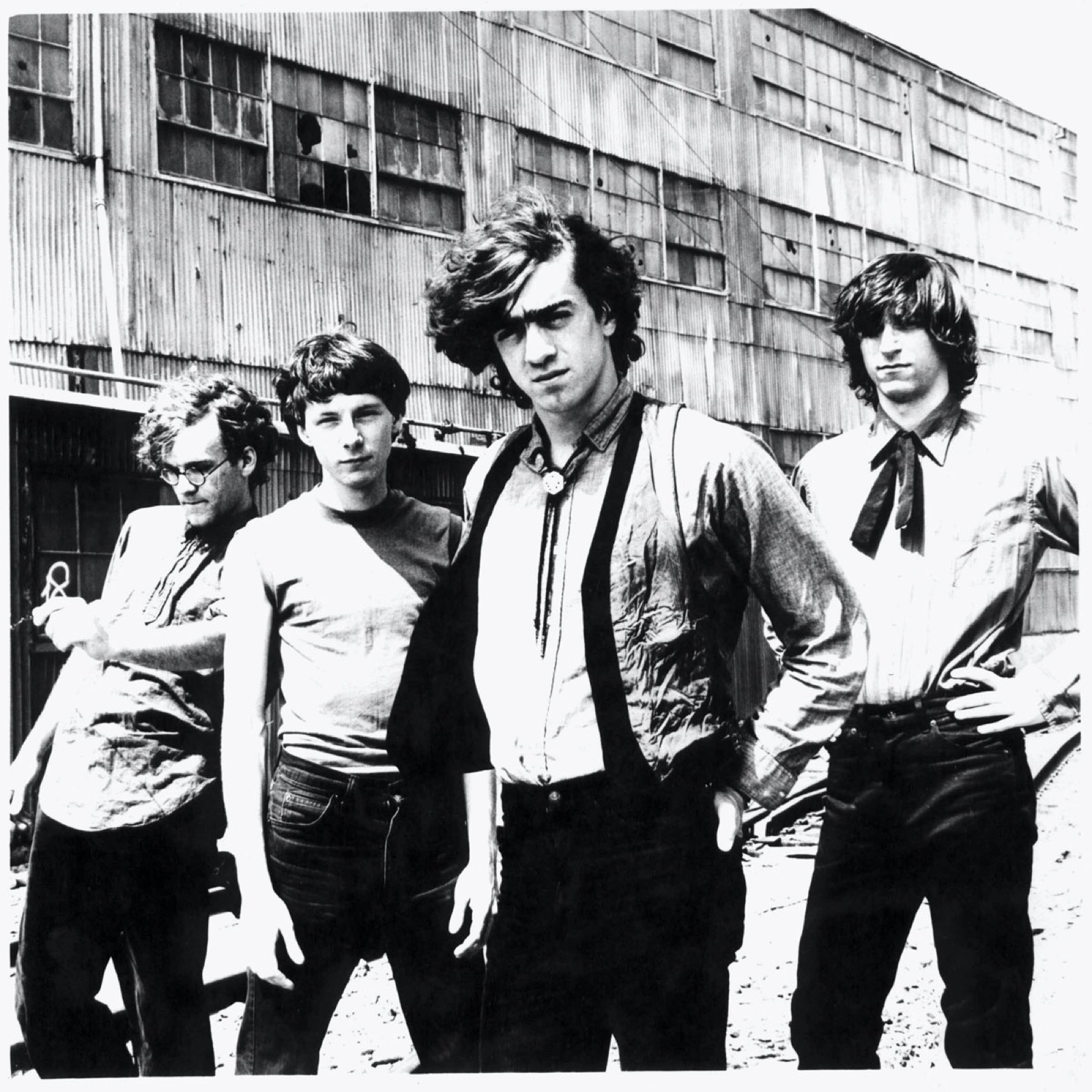

Photo of R.E.M. (1984) by Edward Colver

It was R.E.M.’s ability to sound like a pop band and still address an audience of hipsters that set them up for the kind of success they are now enjoying (just last year, Nirvana used the same formula: highly likeable pop songs combined with a grungy bad attitude). If R.E.M. became the ultimate college radio band—and along with U2, they most certainly were the underground airwaves’ strongest crossover success story—what it mainly served to prove was that college students are basically conservative and conventional in their musical proclivities, and that after years of a steady diet of punk rock—or of cacophonous, screechy noise music of one underground movement or another—they were probably quite pleased to find that something as melodious and pleasant as R.E.M. could now be passed off as alternative. By this account, if sound alone were all that counted, R.E.M. could have won me and millions of other people over years ago. Even though I never much cared for the band, I could always admit that certain R.E.M. songs were astonishingly beautiful—the gorgeously layered guitars on “Fall On Me” and the willful, fitful steadfastness of their cover of a minor sixties hit called “Superman,” both of them on Life’s Rich Pageant, were undeniably catchy. And “Stand,” “Pop Song ’89” and “Orange Crush,” all off of the major-label debut Green, were great, dance-happy fun. But I just couldn’t stand Michael Stipe’s lyrics. I don’t even mind that he slurs his words so much that they’re impossible to understand (Murmur has been jokingly referred to as Mumble); I just hate that Stipe is too deliberately obscure and too fixated on ecology and other politically correct stances to bother writing songs that the less right-minded among us could actually fall in love with. In a recent article in the magazine Pulse!, Stipe’s bandmates Mike Mills and Peter Buck were so stumped by questions about the songs’ meanings that the writer Ira Robbins concluded that deciphering the lyrics is “a task for which membership in R.E.M. apparently isn’t much help.”

Now, of course, for some people not knowing what Stipe’s talking about is the whole point. I’m sure there are listeners who like the way many of his songs are deliberately nonsensical, and I know there are many others who consider Stipe to be something of a hero because he doesn’t write sappy, silly love songs that pander to the lowest common denominator. But I always thought that R.E.M.’s maverick musicality could be combined with a simple, pretty set of thoughtful romantic lyrics to concoct sappy, silly love songs that were, somehow, not so sappy and not so silly. I always thought that if Michael Stipe would just play the game a little bit, R.E.M. could create a masterpiece of a pop album.

That’s precisely what happened with Out of Time, which was an R.E.M. album for the rest of us, for all the people who just didn’t get it. Although Out of Time opens with “Radio Song ’91,” a bit of social commentary that includes a quick rap from Boogie Down Productions’ KRS-One, the ills the song addresses—the stupidity of pop radio—are a bit more, shall we say, run of the mill than the usual. But after that, with the exception of the irritating, nitrous-oxide giddy “Shiny Happy People,” Out of Time is an album of love songs. From the groping uncertainty of “Losing My Religion” to the loneliness of “Half A World Away” to the desperation of “Low” to the ecstasy of “Me in Honey,” for the first time ever R.E.M. was creating penetrable, human songs. This was real-people music dealing with real-people problems.

There are plenty who felt that Stipe’s new concern with relationships, and his move away from the abstractions and wishy-washiness that had marked previous material, was a form of selling out—but I’m pretty sure that it was just a way of growing up. R.E.M. must have known it was time to make an adult record. Simple logic would seem to dictate that it is adolescent to be hung up on love and infatuation, and that it is much more grown-up to be concerned with the World, but R.E.M. proved that the reverse is often more true in the land of rock & roll—this is a band that has best expressed its maturity of thought not through astute social commentary, but in an ability to write about love and relationships with an emotional depth that requires some semblance of adulthood. And not long after Out of Time was released, U2’s album Achtung Baby came out, marking the first time that band produced an album that had nothing to do with apartheid or civil war in Ireland or world peace or political strife or much of anything other than Bono’s girl troubles. It cannot be a coincidence that two bands whose careers have followed a similar trajectory would come to the same creative point at about the same time. And it also cannot be a coincidence that these were both bands’ best albums to date.

So where do they go from here? It will probably be a few years before there are new signs of life from the U2 camp—it might take Bono that much time to recover from how foolish he looked in that leather lamé suit on the Zoo TV tour—but R.E.M. didn’t go on the road after Out of Time, and the follow-up appeared just a year later. Automatic For The People, despite the Marxist, agitprop ring of its title—it’s actually named for a Georgia restaurant—is a sober, somber affair that almost completely lacks the verve and energy of its predecessor. It seems to be the decompression after the tremendous inflation of Out of Time. In simple terms, Out of Time was a great, big, sweeping album, clearly R.E.M.’s bid for a magnum opus, and Automatic has a much narrower, softer focus, as if it were a zonked-out afterthought, or an attempt to say goodbye to all that. I don’t mean this in thematic terms—Automatic marks Stipe’s return to his usual global ponderings, alongside many more intimate songs—but musically this is definitely an album that was recorded sparingly and in a minor key. It is moody and introspective. Even though John Paul Jones, best known as the only member of Led Zeppelin not to make a pact with Satan, was brought in to do string arrangements—which would seem to imply all sorts of grandiose orchestration—any use of violins and cellos and whatnot is extremely simple and organic. Without reading the credits, you might not notice the strings at all. (I mean that as an extreme compliment to Jones—the world does not need another rock album with turgid, orchestral aspirations.)

Automatic opens ominously with the strumming acoustic guitar of “Drive,” the album’s first single, which many have noted bears an eerie resemblance to David Essex’s glam-rock classic “Rock On”—although I think David Bowie’s “Space Oddity,” which is about being alienated in the most literal sense, is a more accurate reference point. Beginning with the monotone chants, “Smack / Crack / Bushwhacked,” it’s clear that this is meant to be a downbeat battle cry for our times. The song by itself is a powerful, forceful statement that makes the most of Stipe’s deadpan delivery, but taken with the accompanying video it is absolutely startling. The clip is very raw—shot in grainy black and white, it shows Stipe in a flesh pit being passed around over the heads and hands of a huge throng of kids. Many of the frames are all arms and flashing light—with Stipe’s striped boxers occasionally peaking out of his shorts. Every so often, the camera cuts to a shot of another member of the band, lost in the crowd, which is getting watered down and broken up by fire hoses. Most people in R.E.M.’s audience will not remember the scenes of police officers hosing down the civil rights protesters in the early sixties, and they may only know cinematic reenactments of anti-war marchers being tear-gassed by the National Guard a decade later, but this new R.E.M. video creates the perfect image of a white riot, nineties style: here kids are gathered in a crowd, a crowd that seems to go on and on, a crowd protesting nothing at all, a crowd that’s just causing a disturbance for its own sake. As Stipe is passed around, he looks gaunt and sickly, and with his arms spread out, he seems to be playing with the image of Jesus on the cross. But giving this video that kind of meaning would be extremely over-determined: the point is that this is a meaningless mass. “What if I ride / What if you walk / What if you rock around the clock / Tick tock,” Stipe sings, and for once his non-sequiturs seem to have a purpose; life is reduced to its central and repetitive futility. You want teenage Armageddon? The video seems to ask. Well you can have it! In the meantime, Stipe’s voice acts as an inciter. “Hey / Kids / Shake a leg / Maybe you’re crazy in the head.” Hey kids, this is your wake-up call! But everyone is too busy passing Stipe around, living in the daydream nation, to even think of waking up. As the clip spirals to a close, images of a creepy, passive violence flash and linger.

Every time I’ve seen the “Drive” video, I have found it embarrassingly mesmerizing, but it is quite clever, and will probably remain so—although once MTV got it rolling on the heavy rotation juggernaut, it began to deteriorate into parody. Just the same, it serves as a fine reminder of the stunning visual charisma that allowed Stipe’s strange white-boy arm-flinging dance in 1991’s “Losing My Religion” video to stick out in so many people’s minds. It’s unfortunate, given this quality, that the band once again won’t be touring, although the subdued nature of this album probably would not work well live. Other than “Drive,” Automatic’s primary masterpiece is the low-key “Everybody Hurts,” a ballad about caring and empathy which pushes Stipe’s voice almost into a falsetto range that makes the song sound an awful lot like “Bridge Over Troubled Water.” In fact, “Everybody Hurts” is an anthem in precisely that vein, and it’s so sweet and sad and sorrowful and heartfelt that it would be kind of hokey if it weren’t so beautiful. To keep the song in balance, R.E.M. used an old metronome-like drum machine instead of real drums, giving the beat a wooden, mechanical quality, in juxtaposition to Mike Mills’s languid keyboards and Stipe’s earnest singing. The idea, Mills explained in an interview, was for the sound to be “human and non-human at the same time.” And “Everybody Hurts” is unique for R.E.M.’s body of work in that it offers one of the rare moments when Stipe seems to lose control, seems to be stretching his voice to allow emotion (as opposed to rumination) to get the best of him. Normally, R.E.M.’s touches of vulnerability have been provided by Mills’s background singing—and his vocal trade-offs with Stipe give the song real tenderness—but on “Everybody Hurts,” the elements are reduced to so little instrumentation that it is up to Stipe to provide all human depth, and he performs the task admirably.

Issue 3, Winter 1993

On the other hand, “Try Not To Breathe,” which has a winding, waltz-like pace, is the picture of Stipe in complete control. He seems to be contemplating suicide, perhaps Dr. Kevorkian style, and claiming he can take control of the most difficult task of all—the ability to stop breathing (“I will try not to worry you / I have seen things that you will never see / Leave it to memory / And dare me to breathe”). The song itself has a rolling, lilting quality that’s R.E.M.’s signature sound, which is why it seems calm and contented, despite the subject matter. Of course, mortality is a big topic on this album—sometimes dealt with in a humorous light, as Andy Kaufman and Elvis Presley, along with the “horrible asp” that troubled Egypt, are imagined in the afterlife in “Man on the Moon” (“Let’s play Twister / Let’s play Risk / I’ll see you in heaven if you make the list”), but more often in the mournful tone of the dolorous, heavy “Sweetness Follows.”

The nonsense quotient on this album is up to Stipe’s usual levels—on “Monty Got a Raw Deal,” Stipe even confesses that “nonsense has a welcome ring”—although perhaps, after all this time, it’s gotten so that I actually appreciate the seemingly random references to black-eyed peas, Nescafé and ice, Dr. Seuss, fallen stars, and The Cat in the Hat that Stipe makes in the wacked-out “Sidewinder Sleeps Tonight,” which seems, in the final analysis, to be a song about a diner payphone (don’t ask). I think that after the practice of actually writing linear, straightforward songs for Out of Time, Stipe’s gibberish has gotten better. But I’ll be damned if anyone can figure out what’s going on with all the sampled voices in “Star Me Kitten,” which is really supposed to be called “Fuck Me Kitten” (as in “**** Me Kitten”). At any rate, when Stipe finally asks, “Have we lost our minds?” it seems he’s at long last on to something.

Perhaps Stipe’s loveliest lyrics—which are almost old-fashioned and quaint in their way—are contained in the narrative of “Nightswimming,” an elegiac reminiscence of youthful skinny-dipping—of youthful everything—with images so strong you can taste the longing in Stipe’s voice:

Nightswimming deserves a quiet night

I’m not sure all these people understand

It’s not like years ago

The fear of getting caught

The recklessness of water

They cannot see me naked

These things they go away

Replaced by everyday

Sadly, from a musical vantage point, “Nightswimming” is one of the less interesting songs on the album, pretty but plain, all strings and piano, but the nature of nostalgia is often more pleasant than exciting. And the ability to look back and evaluate the past in a thoughtful, unsentimental fashion was the one missing element in the emotional growth R.E.M. tried for on Out of Time. That was an album so firmly grounded in the present tense that it never surprised me to find out that there were people—my stepmother, for instance, or kids under the age of consent—who actually thought Out of Time was R.E.M.’s first album. It had all the forward-thinking energy of a debut—and all the spit and polish you’d expect from an experienced group of players. There’s no doubt that Out of Time will always mark a climactic moment in the band’s career, and it will probably be a touchstone for everything that follows—that’s just the way it always is: everyone’s still waiting for Joni Mitchell to make another Blue, for Bob Dylan to come up with another Blood on the Tracks, for the Violent Femmes to match the fucked-up genius of their debut, and for AC/DC to do another Back in Black. It’s admirable that, rather than balk under the pressure or try to duplicate the success, R.E.M. decided to make a good, solid album that suits the place and creative space they’ve arrived at now. Automatic For The People sounds like an album by a band with a strong, illustrious history—and, one hopes, many good years ahead.