City of Colaine in Visions of Other Worlds, 1990, acrylic and enamel on wood, by Howard Finster. Courtesy the Collection of Sheryl & Kevin Wallace and Beatrice Wood Center for the Arts

Mirror House

Howard Finster, my father, and a path to beauty in our broken world

By Garrard Conley

The first time it happened, I must have been five years old, leaning over a ditch that cut through a neighbor’s vegetable garden—and there, where I had once seen nothing, I now saw a flash of gold. The wet soil caught the sunlight at an angle where bits of mica shone like luminous stars. For several minutes I stood transfixed. Then, in a daze, I plunged my hand into the mud; when it emerged, I saw a sparkle on the tip of my finger. I don’t remember telling anyone about my find. I wanted it to belong only to me. It didn’t matter if it turned out this wasn’t gold; the flash was proof that the soil was full of wonder.

By that age, I could already guess the general shape of my father’s response: Why, this is just fool’s gold. Haven’t you seen that before?

Growing up, I knew my father to be a man who spoke plainly about the world, someone whose primary goal for his son was for me to be a practical man. From the age of ten I began working hard for him every summer, mowing lawns, working on cars, “outworking the men,” his employees, at hauling whatever needed to be hauled, often in the oppressively humid Arkansas heat. I was never prouder than in the moments when he bragged about my endurance, my manliness.

Another side of him would come out at night, often after a mandatory session of wrestling, after he had held me in a headlock until I stopped “whining”—the term he used for my crying—and worked my way out of it. I became claustrophobic during these early years, and still am to a certain degree, but these sessions taught me to slow my breathing and focus on an element of the room to calm my spiraling fear. Once I was able to work my way out of his hold, he would relax. I imagine these lessons were no more fun for him than they were for me; they were his way of protecting me from what was to come, as he saw it: a life of violence and struggle as the owner of a cotton gin in a dying farming community of one hundred people. For reasons I didn’t understand, my father was always getting into fights, and the stories of his childhood and adolescence were stories of extreme near-death experiences.

Lying on our living room carpet, exhausted from wrestling, he would wrap one arm around me and pull me up to his chest, where I would lay my head and listen to his breathing. Then, often for hours at a time, my real father would emerge, telling me stories of his inventions, his Lovecraftian creations: the automatic toilet paper dispenser he developed blueprints for years before anyone else was talking about it; the wolf-orang, a wolf-orangutan chimera, waiting in our trees and pressing its furry face to the windows at night, searching for entry. My father told me he would protect me from the monsters, and I believed him.

The world is familiar to most people, even if they have not seen most of it. Especially if they have not seen most of it. In very short order, the concerns of life lessen our capacity for wonder. The CALS Encyclopedia of Arkansas provides one of the few surviving records of my hometown of one hundred people: “In 2001, the only remaining store and the cotton gin ceased operations, leaving the Baptist church as the only entity left in the community. Milligan Ridge, like many small Arkansas farming communities, could not compete with the forces of change.”

The lesson was clear: No matter how hard we tried, no matter how tough we became, we “could not compete.” Even so, in the mid-90s, when a corporate competitor wooed away most of our gin’s customers, my father did not give up. He was still the practical man who would find another job, another life for us. The one thing that did change, however, was my father’s nightly storytelling, which disappeared from our lives. I was thirteen. The part of me that was most like him—the one who dreamed wonders—was hidden away in an effort to become the man he wanted me to be, at least for a while, and a tougher exterior emerged.

My father moved us to another Arkansas town farther west, a larger town with a two-screen theater that played mostly G-rated movies and a Walmart Supercenter with a McDonald’s inside. My father, former cotton gin owner, became a Ford dealer overnight, and my mother, whose family had owned the cotton gin before my dad, wrote thank-you notes at a small desk in the dealership’s showroom. Summers I washed cars in the service department, befriending workers whose lives were full of violence: bar fights, jail, drug addiction. A man everyone called Wild Thing told me a story about his wife, who had been critically injured when a train collided with her car as she was driving back from an affair, X-rated photographs in the passenger seat. God punishes those who err from the righteous path, he told me. After it was obvious to me that I might soon be tempted to err from the righteous path with another boy, I found a girlfriend. We dated for a few years, hopping between movie theater and Walmart McDonald’s enough times to grow sick of them, until I broke up with her without explanation. When I left for college in 2003, my father had already surrendered to the Lord, suddenly becoming a Baptist preacher, while the Ford dealership floundered and eventually shuttered like everything else in our lives. A year later, my parents forced me to attend a conversion therapy facility in Memphis, threatening to cut me off from my family if I didn’t go. It would make me stronger, my father told me. It would protect me from the monsters out there who would want to hurt a faggot like me. I remember feeling as though the ground beneath my feet could no longer be trusted. I could no longer recognize myself in the mirror, dead eyes warning me that soon the rest of my body would be dead as well if I continued with my father’s lessons. I had seen enough of the world to know it had nothing more to show me.

Even so, from time to time I could still spot those flashes of wonder. After I returned from Memphis with my queerness intact, I read Thoreau and felt compelled to study the ants beside my college campus’s lake, watching the order they make if only you stare long enough. Once, after a dormmate and I made each other come several times in his room, I awoke to see those ants descending from the windowsill onto his soiled t-shirt with ferocious industry. Sex brought me back to my sense of awe, if only for a moment. After a while, though, even sex became familiar.

For most of us, the world shrinks and we try to do something about it. We plan for vacations, go for a Honolulu cure as Joan Didion would have it, find religion as my father did.

Speaking to me just last month on the phone, he sounded like a changed man, the one who once whispered in my ear about the wolf-orang. Gone is the man of headlocks and ultimatums; in his place is someone who regularly weeps at the sight of trees, who asks my forgiveness if he was ever wrong. “I fell asleep and witnessed a new invention,” he says, his voice more expressive than I’ve ever heard it. He tells me the sensation is of digging something whole out of the ground. He doesn’t want me to mention it here, for fear of prying eyes, so I will only say that it involves dogs and walking canes and that, like most As Seen on TV long shots, it could make millions. I have never known him to lie, so when next he tells me that Jesus bleeds onto his bedsheets at night, I consider this to be a bona fide vision. What some of us wouldn’t give to be spiritually bled upon, if only we knew that the blood came to us whole, unmediated by the usual human bullshit.

I can sometimes be ungenerous in the face of his conversion. I want to ask him where this person was when I needed him most. How is it that he can access this creative self so late in life while I, the man he created in his image, cannot? I want to tell him that I wasn’t the one who needed converting, that I already was where he is now but that he spoiled it with his lessons. He has made my reversion to a pure creative state nearly impossible. Because of him, sometimes it feels like I have already seen too much, I’m too world-weary at the age of thirty-five. I’m like the unflattering protagonist of Flannery O’Connor’s “Good Country People,” overeducated in certain specialized ways which make me narrow and ripe for plunder. “I’m one of those people who see through to nothing,” Joy-Hulga says, just moments before she is duped into loving a man who only wants to steal her artificial leg. The problem of growing old at a young age is that, just when you think you have seen it all, you can be blind to the things you really need to see.

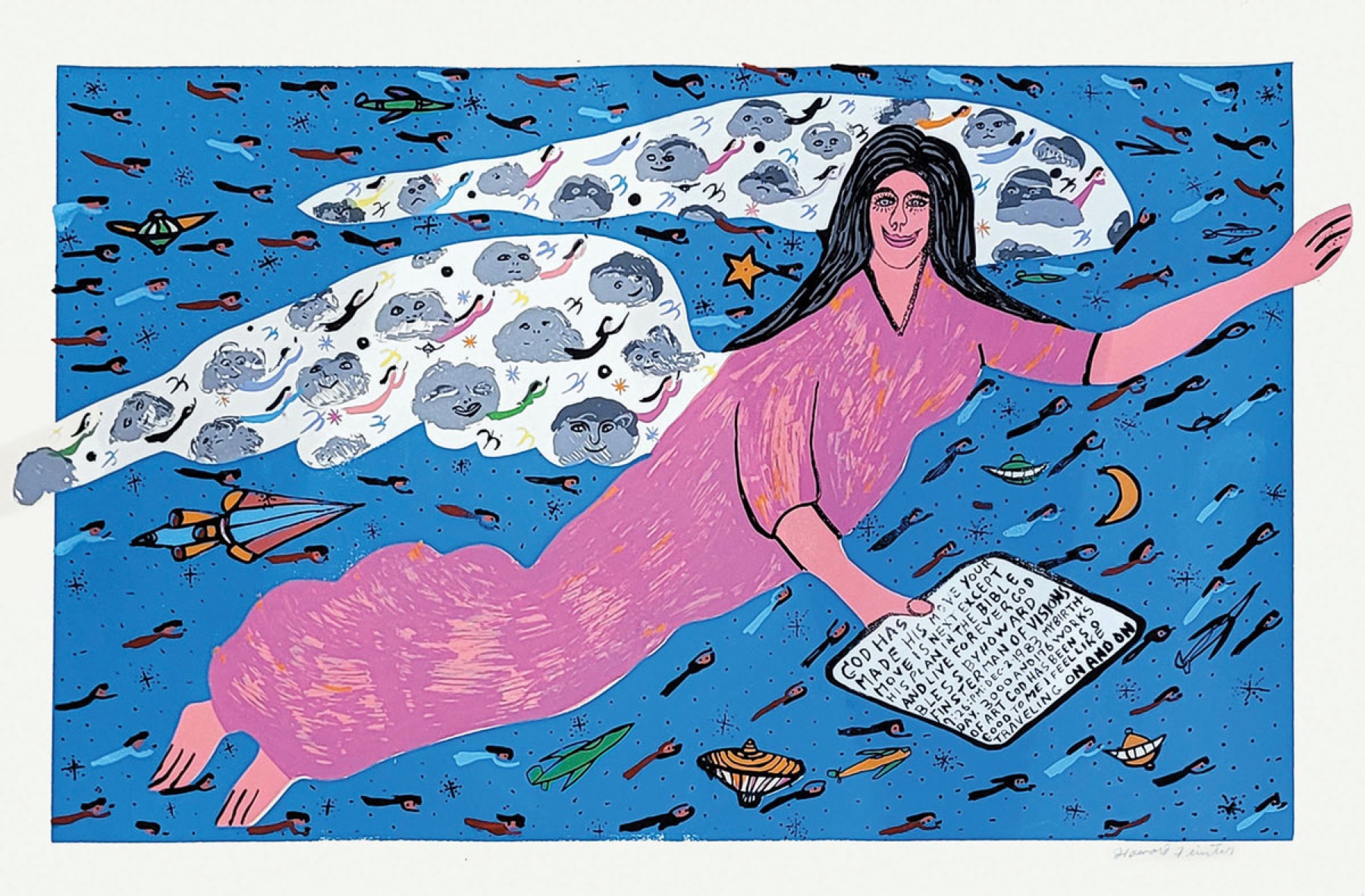

Birthday Angel, 2000, original silkscreen on paper, by Howard Finster. Courtesy the Howard Finster Vision House Museum

Where The Living Water Flows, 1990, enamel and marker on wood, by Howard Finster. Courtesy the Collection of Sheryl & Kevin Wallace and Beatrice Wood Center for the Arts

Photo of Howard Finster circa 1990. Photo © Jim Morgenthaler

Which leads me to Howard Finster, a self-proclaimed prophet, former Baptist preacher, and folk artist from Pennville, Georgia, who, at the 1976 Missing Pieces Atlanta Historical Society folk art exhibition, spoke of inventions like “’frigerators,” “washin’ machines,” and automobiles as “all in the earth . . . hidden.” In that same speech, recorded by Tom Patterson in Howard Finster, Stranger from Another World: Man of Visions Now on this Earth, Finster, age 60, stood before Governor Busbee and “Miz Busbee” and declared that every human discovery was first “hid in the earth” and that every artist must bring out the “Hidden Man o’ the Heart.”

Less than a year before this speech, at roughly the same age my father was when he received his calling to the ministry, Finster claimed to have witnessed a vision while repairing one of his bicycles. The way he told it over the years, in hundreds of interviews that shifted with the improvisations of a naturally gifted oral storyteller, Finster dipped his finger in some white tractor enamel “to patch somethin’” when he saw a face smiling back at him on the pad of his index finger. “Paint sacred art,” the face said. In dozens of recorded interviews, many of which can be found in David Fetcho’s documentary I Can Feel Another Planet in My Soul, the divine command never changes: “Paint sacred art.” Neither does the response. Incredulous, Finster tells the face he cannot paint. “How do you know? How do you know? How do you know?” the face says. “Well, how do I know?” Finster finally replies.

Like my father, Finster held dozens of jobs before he found his calling. Now he had only one job: to make art. In the decade to follow, Finster became one of the most widely known artists in America, a regular staple at Phyllis Kind’s trendsetting New York gallery, with bands like R.E.M. and Talking Heads commissioning Finster’s art for album covers, and Johnny Carson’s Tonight Show inviting him to sing and pick at his banjo. His ubiquity seemed to mirror his art: nearly every surface he painted was filled with minutiae. Where another artist might allow for the open sky of landscape painting, Finster often crowded his skies with impossibly tall towers, angels, scrolls, sermons which stretched across the horizon—a grand display of what some critics associate with horror vacui, the fear of empty spaces, though I have come to see Finster’s excess as a fear of waste. According to the Paradise Garden Foundation, whose goal it is to preserve and maintain Finster’s vision, Finster created 46,991 sacred objects by the time of his death in October 2001. He kept a running log beside him at all times, often fashioning stray bits of wood to suit the purpose. The one I saw, mounted to a wall in the Paradise Garden gift shop and gallery annex, resembled the markings a loving family might keep of a growing child as he aged out of the home.

I first discovered Finster’s work as part of the Stranger in Paradise exhibition at the Jule Collins Smith Museum of Fine Art at Auburn University. I was working as a TA for a poetry professor and, much like his students, who had been tasked with creating ekphrastic poetry out of Finster’s visions, I found the unevenly painted angels and devils, along with the depiction of a cavernous Hell filled with Finster’s Baptist sermons, both incredibly familiar and strangely foreign. My father’s drawings, which he sometimes used to illustrate the points of his sermons, were not so different from these. The evangelical tracts of Chick Publications, once so ubiquitous in Arkansas rest stops and gas station bathrooms, with gruesome depictions of death and Hell awaiting every unbeliever, were only a few degrees hotter than Finster. What was different, however, was the sense that all of these paintings were part of a larger sensibility, something just beyond the frame, which I had never seen before.

Though I would not step foot there until many years later, I must have sensed that a place like Paradise Garden existed. Finster’s largest project—and the one he declared was his most important—was a four-acre dreamscape in Pennville, Georgia, filled with sculptural objects recycled from whatever was on hand or donated at the time of their creation. Inspired by the roadside attractions and gardens of many Southern self-taught artists and entrepreneurs before him, Finster, “commissioned by God,” conceived of a place where he would “collect one of every invention in the world.” Over the years, however, as his visions developed, the project became much stranger, and much more complex: a massive tower made of bicycle parts; a concrete shoe the size of Finster himself, who can be seen reclining on the vamp with a rather mischievous expression in one of biographer J. F. Turner’s photos; a pump house made of Coke bottles; concrete walls and sidewalks embedded with artifacts like broken glass, marbles, and children’s toys, many of which were donated by fans over the years, sculpted into a kind of heavenly gateway; and the World’s Folk Art Church, a five-story round-tiered wooden structure which Finster, with no previous architectural experience, built atop an existing church, spire and all, much to the surprise and awe of Lord Aeck Sargent, the architectural firm working with the Paradise Garden Foundation to restore the church.

Stepping onto the property, as I did on a rainy afternoon in February, you might believe you are seeing a version of the South you have seen before. Here sit the discarded bits and pieces people left behind in the struggle to survive, the junkyard where rapidly mechanized industries came to die, the site where fire and brimstone scripture meets kitschy phrases like “angels are perfect.” As I approached the Rolling Chair Ramp, a wheelchair-accessible elevated walkway connecting two halves of the garden, I spotted pod-like glass enclosures beneath the walkway which had been filled with rusted cogs and piles of abandoned machinery, Finster’s so-called “inventions,” which in my family’s experience had done very little to keep the South economically prosperous. No doubt at some point there had been reason to celebrate their creation, though now I could only think of the houses I had seen on the drive here whose yards were filled with discarded cars and washing machines, the kind of junk Hollywood loves to fetishize in its depictions of Appalachia. Yet the longer I stared into these pods, perhaps because I was clued into the idea that this garden was conceived as art, I began to detect striking associations among the objects, a kind of dialectic hum which made me reconsider my former views.

One pod was so decidedly incongruous it could have come from an Eisenstein montage: silver samovar sitting atop a hospital gurney—they were twins, creature comfort and sickness. I was reminded of days in my youth when, pausing from my lawn mowing duties, I would sneak into some shed at the outskirts of the cotton gin to examine the objects inside. There was always some unseen force lurking in the arrangement of rusty tools, something powerful I couldn’t name, terrifying and too big to put into words. Later, when I learned about the history of the cotton gin’s relationship to slavery and the exploitation of Black labor—when my mother, after much prodding, told me that, as a little girl, she had seen a white bus filled with Black laborers who picked the fields and were paid by the pound—I associated that feeling with my growing awareness of this country’s brutal past. As Eula Biss writes in “Time and Distance Overcome” regarding the history of the telephone pole and its role in the lynching of Black men: “Nothing is innocent . . . but nothing, I would like to think, remains unrepentant.” I wanted to believe that Biss was right, yet I could never be so sure these objects were repentant, or, to state it more directly in my case, that my family ever was, despite their assurances that they were neither racist nor homophobic. If they were so sorry, why had they kept quiet for so long? Why did these apologies come only after being prodded with difficult questions?

On a personal level, a few years ago, when my father told me he was sorry for what my counselors had done to me “at that camp,” I did not experience his apology as repentance. I had waited so long for that moment, and now that it had arrived I found I had no way of measuring his heart. The problem with repentance as it is historically defined is that only God can see it; we cannot know another human being’s interior. It only gets more complicated with objects—or artifacts, as Finster aptly names them. They can rarely if ever exist in a vacuum; they take on the associations of history and come to be seen as an extension and symbol of our civilization; as such, their only true repentance exists in a world where the wrongs have already been righted, and that world does not currently exist. Once, when my friend, the author Garth Greenwell, and I were on tour together in North Carolina, I offered him some vapid comment about the beauty of the houses, many of which were done up in mock plantation style, to which Greenwell replied that they looked like violence to him. For some of us, nothing aesthetically pleasing in the South ever remains purely so. But if you view the world this way at all moments of your existence, the violence extends outward indefinitely and there is no sacred place on this earth, there is always some dark association ready to bubble up wherever you are. The question, for me, becomes not so much a moral as an existential one: How can we find joy and beauty in a broken world?

Here I was, standing in the middle of an art installation by a man so very much like my father, a man who preached a hundred Baptist sermons, someone happy to paint Eli Whitney and His Cotton Gin, with “God ment for people to be clothed. This is the facts of the truth” scrawled on his canvas. I have more than once been accused of being a masochist, but I believe that my presence in Pennville, Georgia, that February afternoon had less to do with torturing myself than with searching for this path to beauty in a broken world: not by pretending that the world didn’t exist, as was my usual method, but by digging through it to find that young boy who had been left behind in Milligan Ridge, the one so very pleased to discover a brilliant flash of gold. Finster claimed he could channel his visions into a heavenly paradise, and I couldn’t deny that 46,991 artworks helped make his case. One day you look down to see the answer to life on the tip of your finger. The associations change in an instant; artifacts become strange and wondrous when juxtaposed. Gone is all doubt and struggle. In their place: a true home on this earth for all who want it, one that can never be taken away by the “forces of change.”

After my first walk through the garden, I headed to my Finster-themed Airbnb bungalow sitting at the property’s edge and drank an entire bottle of sparkling wine.

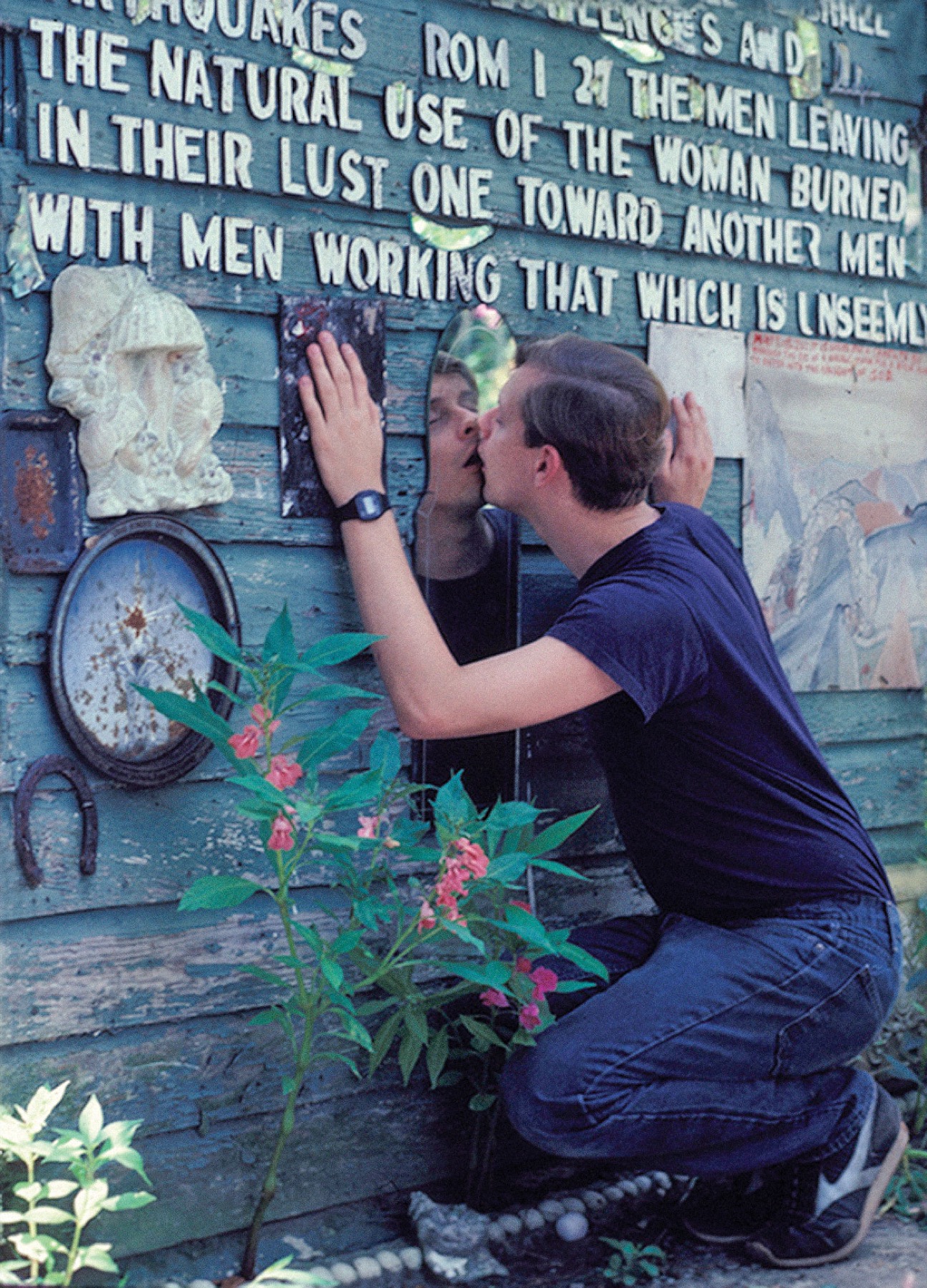

Photo of Robert Sherer at Paradise Garden by Robert Poss. Courtesy the artist

I was not the first queer artist to make the pilgrimage to Paradise Garden in search of a home. Just three months before his death from AIDS, Keith Haring, whom Finster referred to as “Chief Haring,” visited the self-taught artist in his studio, helping construct a giant Coke bottle sculpture and later inspiring Finster to create two of Haring’s signature faceless figures for the garden. When I awoke the following morning, hungover, I was surprised to find roughly a dozen wooden cutouts of child-size Haring figures, all in cheery primary colors, propped beside a small wooden building just outside my kitchen window. Later that morning I asked Donnie Davis, operations coordinator of the Paradise Garden Foundation, why these figures had been stacked as they were, seemingly hidden away from visitors.

“They used to be on the fence,” Davis told me, “but they started to rot. They were made by local high schoolers.”

The image was disorienting, another jarring juxtaposition. I had first encountered Haring’s figures while standing before his famous Once Upon a Time mural in the bathroom of Manhattan’s LGBT Community Center, where they fucked and sucked and spawned from the tips of giant penises in orgiastic abandon, a tribute to gay male promiscuity before HIV and AIDS, and the fear that came with them, ravished the queer community. It was odd to think of Haring’s figures facing a rural neighborhood in which, within only a few blocks of my late morning run, I had spotted several Thin Blue Line flags and a sign which simply read god. guns. trump. As Davis led me through the Rolling Chair Ramp Gallery, which featured hundreds of donated art pieces and handwritten notes from Finster’s fans, I now viewed the phone numbers lovingly inscribed beside several entries with a new pair of eyes, part of that same drive for intimate connection I had discovered in cruisy bathrooms across the country.

“Howard welcomed all who visited,” Davis assured me.

I was beginning to understand this about Finster—perhaps I had always understood this, his willingness to proselytize in the same way as Christ and men like my father did—but I still wondered what brought Haring here aside from what little I could glean from my superficial understanding of folk art. I found one explanation from Gil Vazquez, president of the Keith Haring Foundation, in an interview with Sotheby’s: “Keith was attracted to the innocence of that and the purity of [Finster’s lack of formal training]. There was just something innocent and naive about it—it had nothing to do with the art world and nothing to do with aspirations to be a known artist.”

From J. F. Turner’s Howard Finster, Man of Visions:

I was a farmer. I could plow, cultivate, plant, sow, gather, and preserve, all it took to be a farmer. But I finally quit. I done hammer out blacksmith irons with white heat and shoed mules, but I finally quit. I begin preaching as a pastor and pastored churches for many years, but finally quit. I mounted animals, stuffed them, treated them with formality-hide, and even skinned a chicken so small its skin was almost thin as tissue paper. I stuffed him, sew him up and mounted him on a board, standing up and eating corn from a little pan, and had corn in the pan. But I finally quit. I told a few fortunes as a mind reader but I finally quit. . . . I became a textile employee and learned to wind thread and work with cotton fabrics, but quit. I became a machine fixer in a glove mill and could fix machines, but I quit. I worked in a dye house dyeing cloth, became a cloth inspector, and quit. I took up carpenter work, built houses, remodeled flooring, tiling, plumbing, and pipe work, but I quit . . . I even made bricks and blocks with my own mold and build my first home, but I quit. . . . In 1976 I begin folk art painting and I don’t think I will ever quit because I can do all these things together in folk art painting. I find no end to folk art painting, and I don’t think no artist on earth found the end of art.

—Howard Finster, 1976

Nothing seems to have ever been lost on Finster. He collected everything around him and repurposed it for his art. In this way, he belongs to the great Panglossian tradition of American artists like Walt Whitman, who worshiped invention and humanity indiscriminately. Of objects: “You name any valuable thing that is of benefit to the human race and you are naming something that is being wasted every day in our country.” Of people: “I never met a person that I didn’t love.” Perhaps what brought someone like Haring to Paradise Garden is this sense that nothing is truly wasted in a life, that art is endless even if life isn’t, that the bad and the good can equally serve as fuel for creativity. “I built this park of broken pieces to try to mend a broken world of people who are traveling their last road,” Finster said. “I took the pieces you threw away and put them together by night and day. Washed by rain, dried by sun, a million pieces, all in one.”

Those last few sentences, part of a poem Finster revised over the decades, greet visitors in various places throughout the garden, a powerful thesis statement which, to someone like myself, has a complicated ring to it. The language of wholeness, of brokenness, of welcoming a lost sheep into the fold—this is also the language of so much harmful Evangelical Christianity. Cue R.E.M.

Yet this is also the language of love, I know. I have felt this wholeness with my family, with both my mother and my father. I have felt this with my husband, my closest friends. Sometimes, quite unexpectedly, I feel as if love has come to me whole, without asking anything in return: a true miracle. It invents and reinvents itself again and again. Imagine feeling this every day, never meeting a person you didn’t love. If you can truly feel this, you might believe in paradise.

From a quick Google search on my phone later that February afternoon, I also learned about Robert Sherer, a Southern gay visual artist who, at the beginning of the AIDS crisis, having lost many friends to suicide and disease, found a home in Paradise Garden. Sherer, who later shared his story with me over Zoom, said that he “wasn’t doing well mentally” at the time. “Howard knew that I was troubled,” Sherer said. “I was nihilistic, even suicidal.” Upon meeting Sherer, Finster told him he could stay on his property for as long as he wanted any time he needed. “I would go up there and stay for weeks or months at a time,” Sherer said. He used his knowledge of botany to help out in the garden, spending entire days with Finster, both of them in their own world together. They soon found they had much in common. Both had grown up on small farms in Alabama, both were artists, and both seemed to be outsiders viewing a world that was inherently strange, with Finster claiming at times that he was a “stranger from another world.”

“My dad is very much like Howard,” Sherer told me. “After all these years, when I hear him, I think, my God, that could almost be my dad’s voice.” Being around this father figure, according to Sherer, literally saved his life by giving him a space to dry up and escape the party scene in Atlanta.

There were differences between these men, of course, arising from the remnants of Finster’s past as a Baptist preacher. Sherer told me that Finster was worried Sherer would burn in Hell for all eternity. Once, Finster asked him to plant flowers around a small shack which featured hand-painted Leviticus verses, statements against homosexuality which live right next to those about shrimp and menstruation. Sherer, uncomfortable with the task but prepared to rebel in clever fashion, planted touch-me-nots around the base of the shack. Later, when Finster caught him showering outdoors with a male friend, both young men “in a state of excitation while making out pretty hot and heavy,” the result was unlike anything Sherer had expected. “He just said, ‘Y’all get dressed. The wife’s gonna make us lunch now.’” Finster was silent for the rest of the day. After several hours, Sherer finally asked if Finster was going to kick him off the property, to which Finster simply responded, “No, all I’ve got to say about that is: a man has needs.” What followed the next day was Finster’s joke: “What do they call gay people in the Deep South? Homo-sex-y’alls.” After that day, Finster seemed to distance himself from the damning verses on his shack, allowing them to fade with time.

“If only it could always be that easy,” I said. It seemed almost too good to be true, that my instincts had led me to a story where all of the typical Deep South bigotry was turned on its head.

I asked Sherer if he knew of any other gay artists who visited Finster. Oh, yes: Andy Warhol had phoned Finster at least once for a three-hour conversation about art. After hanging up the phone, Finster, in typical fashion, turned to Sherer and said, “I just spoke to some young artist named Andy Warhol. He told me he was an artist also.”

After my talk with Davis, the operations coordinator, I waited until sunset, hoping to see the garden at its most intimate. I was the only one on the property that night. After months in the suburbs of Atlanta for a new teaching job, I could finally see the night sky again, all the stars I had once tried to memorize but had mostly forgotten. Making my way through the mosaic pathways, I couldn’t help but notice the decay of Finster’s garden, the stark contrast between what I had seen in pictures during its heyday and what now stood before me. I thought of a poem a close friend had sent me a few days earlier, “Eden” by Ina Rousseau:

Somewhere in Eden, after all this time,

does there still stand, like a city in ruins,

forsaken, doomed to slow decay,

the failed garden?

Finster, on the end of the world: “The world started with a beautiful garden, so why not let it end with a beautiful garden?” I would never see it at its most beautiful, no matter how faithfully the Paradise Garden Foundation would be able to restore it, so I would have to make do with what was, with reality as it stood before me.

I discovered a small shack, really a glorified deer stand, raised above the trickling streams Finster had carved out to drain the swampland upon which Paradise Garden sits. The shack’s exterior reflected the dim stringed lights hung over the pathways; every inch of its surface was covered in hundreds of small rectangular mirrors held in place by rusted nails molded over their edges. The Mirror House, it was called. I thought of the Leviticus shack and wondered if that, too, had been repurposed to make something more beautiful. Once inside, I had the sensation of being suspended in the night air. Every surface of the interior was covered in mirrors: on the walls were large rectangular mirrors, and the floor was made of broken shards which looked to have been glued together. I stared down at my reflection. I couldn’t really see myself; all I could see, in what seemed like a limitless number, were shadows of myself.