The Guidebook to the Evaluation of Revelatory Phenomena

By Jeremy Griffin

Illustration by Carter/Reddy. Photograph by myskiv - Adobe Stock

1993

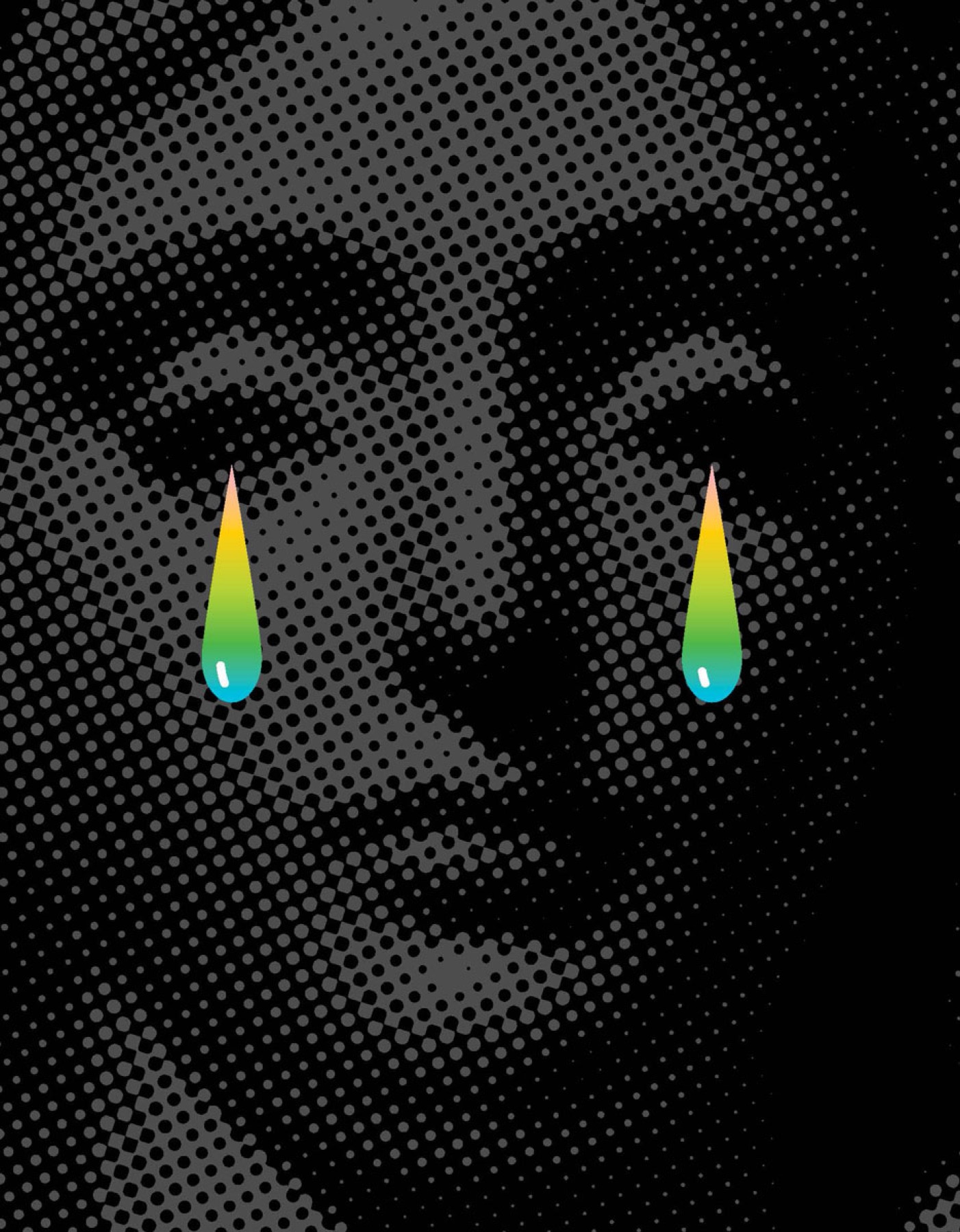

At over seven feet tall, including the three-foot base, the statue was big enough that Connelly had to teeter on a wobbly stepladder to examine the eyes, which were bulbous and heavy-lidded, as if the figure were on the verge of sleep. It was a bronze depiction of the Virgin Mary, sculpted around a plaster cast, and if the parishioners of Our Lady of the Nazarene were to be believed, it had been weeping oil for the past two days.

“You haven’t seen anybody tampering with it?” Connelly asked Father Ortiz, who was hovering behind him like a giddy child, worrying the tiny wooden cross around his neck.

“Never. Nobody here would do that.”

You’d be surprised by what people will do, Connelly almost retorted, but as a priest he was supposed to remain optimistic. He didn’t want to come across as cynical, a drama queen as Allison would have called him. His late sister, ever the pragmatist. And while it never failed to make Connelly feel chastened, now he would give anything to hear it again, to be teased by his big sister once more.

With his Polaroid, he snapped a few pictures of the statue’s face, slick with moisture, like water dribbling down a rockface, and then shook the flimsy prints to develop them. With his free hand, he dipped his fingertip into one of the two tracks of liquid and sniffed it. Sweet, florid. “It’s scented.”

“It’s sacramental then, yes?” Father Ortiz asked.

“Can’t say yet,” Connelly replied, descending the ladder. Palming the sweat off his forehead—like everything else in the church the AC was on the fritz, and the sanctuary was stifling—he stood back to examine the statue in its entirety, the figure’s veiled head angled downward in an attitude of serene benevolence, palms together at the clavicle.

“Esto es un milagro,” Father Ortiz whispered, bringing the cross to his lips. It is a miracle.

Connelly didn’t bother to point out that it was far too early to make such a determination. Not to mention that, according to the sixty-page Guidebook to the Evaluation of Revelatory Phenomena, disseminated through the Vatican’s Office of Pontifical Commissions, the diocese couldn’t make such a proclamation—that was up to the Holy See, and it generally took a few hundred years. Besides, in all likelihood there was an earthly explanation: the Church, for all its mystery, was no stranger to hoaxes.

Still, no need to dash the father’s hopes just yet. Or, for that matter, the hopes of the fifty or so congregants lingering outside in the parking lot to see the statue, La Virgen Llorona as they had come to refer to it, to witness proof of the divine. They would find out soon enough that there were no rewards for their faith.

After giving the figure a cursory examination, Connelly and Father Ortiz retired to the father’s office to review the camcorder footage one of the congregants had taken the previous day. The room was little more than a converted supply closet in the back of the chapel, rank with old incense and mold, barely big enough to accommodate the battered metal desk behind which both men now sat. Leaning in close enough to the small grainy TV screen that their heads almost touched, they observed the shaky footage of the liquid streaming down the length of the statue. A chorus of gasps and invocations rose from the crowd of observers as the oil dampened the cream-colored cloth on which the statue sat.

“Tomorrow we’ll take a look at the ceiling, see if there are any leaks,” Connelly said.

“We checked. It was patched last year after Hurricane Andrew.”

“I still need to look.”

“Yes, of course.”

On the screen, the point of view swung away from the statue, out over the roomful of witnesses, some of them praying silently with their eyes shut, others holding their arms aloft in exaltation.

“And I’ll need to talk to these folks,” Connelly added.

“These are good people.” Father Ortiz replied, a thorn of defensiveness in his voice. “They wouldn’t have anything to do with this.”

“I understand,” Connelly said. “This is just protocol. It’s required.”

With a nod that said he wasn’t entirely sold on the idea, the father returned his attention to the screen. What Connelly wanted to say but had once more stopped himself from voicing for fear of invoking his sister’s imaginary mockery was, Everyone has something to hide.

Our Lady of the Nazarene was a boxy brick structure situated on a boggy parcel of land just outside of Ville Platte. The white paint was flecked and peeling, the steeple canted to one side like a party hat. Half of the stained-glass windows were shattered, covered over with waterlogged cardboard. Connelly couldn’t help thinking that the sixty-five congregants would have been better off abandoning it, finding a new house of worship, someplace other than this crime-ridden burg of shuttered businesses. But then, as in the case of his own diocese in Shreveport, the local townships had never been exactly welcoming to immigrants, an attitude that he had been trying for some time to rectify through outreach programs, but with little success.

This, anyway, was the archbishop’s reasoning for tapping him to investigate the statue, because of his relationship with the Hispanic community. Despite his reservations about languishing in the south Louisiana summer sun for who knew how long, Connelly had accepted the appointment, because if someone was indeed playing a trick on the members of the church, it seemed imperative that he be the one to expose it.

Then again, having never taken part in this sort of inquiry, he had no idea what to look for. He was only thirty-five, practically a child in his profession, vice-chancellor of his diocese for less than a year. It probably would have made more sense for the archbishop to have sent a professor or scientist, someone with critical expertise, but discernment of a purported revelatory event could only be undertaken by someone with “sincerity and habitual docility towards Ecclesiastical Authority”—this according to the Guidebook, which Connelly carried in a blue report binder, allowing easy access for note-jotting, and which he had spent the past few days poring over like a student cramming for a test.

Of course, had the archbishop known about Connelly’s state of mind ever since Allison’s murder the previous fall, he surely would have yanked him right out of Our Lady of the Nazarene, possibly even removed him from his own parish. Which might not have been so terrible, because at least then he wouldn’t have had to stand up in front of his congregation week after week blathering about God’s benevolence, his feeling of fraudulence only amplified by his unshakable love for the Church. He loved the sense of community, the rich history of tradition. And his parishioners, he loved them too. He dined with them, went bowling with the youth group. Even something as dismal as administering last rites had its charms because it made him feel useful, an instrument of good.

Strange, then, to know that if anyone could appreciate the glaze of doubt that had settled over his brain, it would have been Allison, the only other churchgoer in the family. As the youngest, Connelly had always been closest with Allison, only two years his senior. Because of their parents’ hectic work schedules (their father a lawyer, their mother a commercial Realtor), and because his other three sisters were much too old to find him interesting, Allison had spent much of their younger years looking after him. They played together in the forest at the edge of their neighborhood, scrabbling up the magnolia trees, lazing amidst the thick-leaved branches. On weekends, they would stay up late watching TV together, sprawled on the living room carpet with their feast of Nilla wafers and bottled sodas. Even now, Connelly couldn’t see a Coca-Cola ad without recalling those evenings with his sister zoned out in front of That Girl and I Dream of Jeannie.

Ironically, it was also Allison who had questioned Connelly’s motivations when he announced to the family, at twenty-two, his interest in attending seminary. In her view, entering into the priesthood was as weighty a commitment as joining the military. “It isn’t a joke, you know,” she’d warned him. They were sitting on her back patio, the rest of the family inside. Overhead, gnats swirled in the glow of the porchlight. “You can’t just coast.”

“I know that. I’m serious about it.”

“You’ve never been serious about anything.”

“That’s not fair,” he protested, though she had a point. He had never been a model student. It was only by the grace of a couple of sympathetic professors that he had eked through college the previous spring, at which point he’d realized how much he’d longed for the stability that the Church had brought him when he was young. He’d always liked helping people—as a teenager he’d gone on mission trips and worked with Habitat for Humanity—and he wanted to impart that sense of stability onto others. He added, “People can change, you know.”

“Not that much.”

“Since when are you such a cynic?”

She batted a mosquito away from her face. “I’m a Christian, but I’m also a realist.”

“Come on, Allie. I was really counting on your support.”

“I’ll support you no matter what,” she said in the tender tone one might use to say goodbye to a friend. Only those closest to her knew that her stony veneer was a façade, that beneath it she was warmhearted almost to a fault. “I know this is a big deal for you. I just need you to understand the kind of commitment you’re making.”

That night, after his daily phone debriefing with the archbishop, in whose voice Connelly could hear the unseemly exhilaration of a man who believed a cardinalship might be in his future, he ordered a BLT from room service. “What brings you to town?” the waitress asked when she delivered the sandwich twenty minutes later.

“I’m doing some work with a local church. I’m a priest.”

The woman’s face lit up. She paused transferring the dishes from the dining cart to the small table in the corner, where Connelly had been studying the bleary Polaroid snapshots, searching for an aperture in the figure, an opening through which to pour the oil. “Wait, are you talking about the statue? The one that’s been crying?”

“You heard about that?”

“Saw it in the news. La Virgen Llorona?”

Connelly deflated a little. Evidently, his advice to Father Ortiz to avoid the press had gone unheeded—although maybe it had been naïve to think that exposure was avoidable at all. Everybody loved a good scoop, especially one that threatened to embarrass the Church. Nonetheless, this would only make it that much more devastating to the community when the whole thing turned out to be a joke.

“Well, I guess the secret’s out,” he said.

Stuffing her hands into the pockets of her black slacks, she said, “So, what do you think, is it a sign from God?” With her narrow frame and bun of hickory-colored hair, she reminded him of Allison, a kind of practical beauty. But then, everyone reminded him of his sister these days.

“I have my doubts.”

“Why?”

“Because if He really wanted to reveal Himself to us, He should start by addressing suffering, not by dazzling us with parlor tricks. Otherwise He’s not much better than a party magician.”

Right away Connelly wished he could cram the words back into his mouth. This wasn’t confession; the woman was just being nice. Plus, hadn’t he counseled people about this very thing, about not holding God accountable for the ills in their lives? The Lord didn’t cause pain without allowing something new to be born, or so claimed Isaiah 66:9. However, now that Connelly had found himself on the receiving end of tragedy, he could think of no better place to direct his anger than the Almighty.

“Sorry,” he muttered, removing a wad of bills from his wallet on the dresser, far more than necessary for a tip. “It’s been a long day.”

“No worries,” she responded, tucking the money into her shirt pocket, nodding her thanks. “I’m Episcopalian anyway.”

On a Tuesday morning the previous September, just before ten o’clock, a man named Gary Iverson strode into the Fort Worth DMV, where he’d been employed until two weeks prior, and sent a spray of semiautomatic gunfire across the lobby. Eleven people were killed, including Allison, who had been there to renew her driver’s license. At the burial, during which Connelly had sat paralyzed beside Allison’s husband and their three children, the priest—a friend who had volunteered to officiate—had read from Revelations, verse 21:4: “He will wipe every tear from their eyes. There will be no more death or mourning or wailing or pain, for the old order of things has passed away.” Later that night, Connelly, unable to sleep in his sister’s chilly guest bedroom, retrieved his Bible from his bag and turned to the passage. Countless times had he recited it for grieving spouses and children and siblings and friends, always enlivened by its hopeful sentiment. Now, though, as he slumped on the edge of the bed in his underwear peering down at the page, the highlighted verses and the notes scribbled in the margins, it seemed to take on a new sort of heft. Something had indeed passed away, of that he was certain. As for what the new order would be, he couldn’t say.

Before he was able to stop himself, he’d torn the page out of the book. For a few moments, all he could do was sit there with it in his lap, unsure of what to do next. He’d never defaced a holy object before, and it felt both obscene and thrilling, not unlike his and Allison’s clumsy forays into cursing when they were kids. When he was certain there would be no smiting from on high, he folded it up and tucked it into the book. Ripping the page out was one thing, but he could hear Allison cautioning him against disposing of it altogether. To her, that would have seemed too final, a door he could never reopen.

Because most of the congregants spoke little English, and because Connelly’s Spanish was rudimentary at best, Father Ortiz translated during the witness interviews, which Connelly captured on a handheld recorder. The questions all came directly from the Guidebook: Did the interviewee know anyone who might benefit from the potential hoax? How, in their estimation, might such an event be faked? If real, did they believe the event to be the work of God or Satan? For the most part, the responses were all the same—nobody knew anything, and Connelly had a feeling that even if they did, they wouldn’t tell him. Most of them regarded him with the apprehension reserved for law enforcement, and in fact that was precisely how he was beginning to feel, like a cop on some gloomy police procedural, pulling at threads that went nowhere.

“The Lord has revealed Himself to us, why don’t you believe it?” one woman said, the church secretary, Anna Lucia Alvarez, who had been seated only feet away from the statue when the phenomenon began.

“It’s not that I don’t believe,” Connelly responded. “But I have to be impartial.”

“How can you be impartial about God?”

“That’s what I’m trying to ascertain, if it really is God’s work.”

“Look around, Father Connelly.” The woman gestured to the small, shabby sanctuary, the rotting pews and the cracks zigging across the concrete floor. She was squat, late seventies probably, her plump face as coarse as a relief map. “We don’t have a lot of money. The Lord knew that if he showed Himself to us, people would come and we’d be rescued. La Virgen Llorona has saved us.”

Connelly studied the woman the way a person might study a postmodern painting, a mixture of admiration and perplexity. She was certainly right about Our Lady of the Nazarene having been rescued from bankruptcy. Whereas the church had barely been treading water a few days ago, now it was drawing in more relief than anyone knew what to do with. In the past three days alone, people from all over the country had sent in over forty thousand in cash donations, and the money was still coming, sometimes in the form of cash-filled envelopes deposited at the base of the statue during visiting hours, alongside the trinkets and letters and candles and photos of loved ones that supplicants would leave in hopes of invoking the Virgin’s grace. But then, that was the issue, wasn’t it? A church on the brink of foreclosure suddenly comes into a fortune—who wouldn’t be skeptical?

Later that afternoon, after the interviews, Connelly and Father Ortiz sat quietly in the priest’s stuffy office. Through the opened windows, over the clatter of the ancient desk fan, they could hear the clamor of the crowd, which had swelled to the hundreds after the footage of La Virgen Llorona had hit the local news. It had taken him nearly ten minutes that morning to find a parking spot amidst the sea of vehicles spilling into the overgrown fields on either side of the parking lot and then to shoulder his way through the mob to the church doors. Some folks had carried poster signs bearing Bible verses; a few others toted giant crosses as if they were auditioning for The Passion Play. Camera crews roved throughout, interviewing anyone who would talk, while a handful of shameless vendors hawked bottles of water and cans of soda for outrageous prices.

“Have you thought about what you’re going to tell your parishioners when this turns out to be hoax?” Connelly asked the father.

“If.”

“Right, if it turns out to be a hoax.”

The priest leaned back in his seat and laced his fingers across his large belly. He was plump in the jolly way of men who have come to terms with their appetites, his bulging ears tufted with silvery fur. “I’m hoping I won’t have to.”

“I just worry about getting their hopes up.”

“Let them hope.” The man touched the cross resting on his broad chest. “These people have very little. For some of them, the church is it. Let them believe that God is speaking to them.”

Connelly let this sit between them for a moment. “That doesn’t strike you as a little reckless?”

Shrugging, the father smiled like a doting parent to a precocious toddler. “What can I tell you? Faith is reckless.”

Iverson’s trial had been predictably short, barely a week. The prosecution assailed the jury with blown-up images of the crime scene, the bodies slumped in molded plastic chairs or splayed out on the scuffed tile floor. Blood spattered the walls like paint cast off a brush. The defense did its best to present Iverson as helplessly troubled, the victim of childhood emotional abuse and neglect, but from his seat in the gallery it was clear to Connelly that the jury wasn’t buying it. And so, when the judge handed down back-to-back life sentences with no chance for parole, nobody—including Connelly—was surprised.

A couple of weeks after the sentencing, Connelly went to see Iverson in the county correctional unit where he was being held before his transfer to Angola. His hope was that looking the man in the eyes might yield some clarity, a chance to forgive, as he advised his own flock to do. However, as soon as the guards had stashed him in the windowless meeting room, used by attorneys to confer privately with their clients, his resolve began to flake away: regardless of what the Scriptures commanded, he didn’t want to forgive this man. A jarring realization, but there it was—in spite of everything he was supposed to stand for, Connelly wanted to know that his own fury was righteous and just.

After nearly twenty minutes, the door clanked open and a handcuffed Iverson shambled into the room, dressed in a blue work shirt and pants that were at least two sizes too big. He was escorted by a towering, square-jawed guard who shoved him into the metal chair on the other side of the bolted-down table, a bit more forcefully than seemed necessary, though Iverson didn’t resist. Once the guard had retreated outside the door, a deadly silence fell over the room.

“Do you remember me?” Connelly said after a few moments.

“Does it matter?”

“I’m Allison Connelly’s brother.”

“If you say so.” Iverson, who had the uninterested aspect of a student trapped in a lecture hall, adjusted his chunky prison-issue glasses, the cuffs clinking between his wrists. At forty-one, he was unremarkable in almost every way: not too tall or short, pasty-skinned with loose auburn curls, bulky but not unmuscular, the kind of person you would forget thirty seconds after meeting. Why this bothered Connelly, he wasn’t sure. Someone murders your sister, you expect something monstrous, something beyond human. But there was nothing extraordinary about the man sitting across from him now. He was just that, a man, a far cry from the demonic entity the prosecution had propounded. “So, what do you want?”

“Honestly, I’m not sure,” Connelly said.

“You come all this way and don’t know why?”

“I want to know if you’re sorry.”

Iverson laughed, a throaty clucking noise. “That’s what you’re looking for, an apology?” He leaned toward Connelly as if to share a confession. “Fine, whatever. I’m sorry for what I did, okay? It wasn’t personal.”

Connelly rubbed his eyes, a headache simmering in the back of his skull. “Why did you do it?”

“I just wasn’t in my right mind, is all I can tell you.”

“Are you in your right mind now?”

“Think so, yeah.”

At first, Connelly didn’t even realize he had sprung out of his seat, not until he heard Iverson grunt in surprise as he gripped a fistful of his wavy hair while the fingers of his other hand wormed their way into the man’s mouth to insert the folded-up page from his Bible, which he’d managed to finagle out of his pocket just before clambering over the table. Iverson gagged and sputtered, though to Connelly’s surprise he didn’t struggle. Curiously, he seemed to accept being force-fed the slip of paper as part of his punishment, which was somehow worse than if he’d tried to defend himself, because it only intensified Connelly’s crazed desire to see him suffer. Fight back, he thought. Give me a reason to hate you. Even when the guard, alerted by the scuffling of chairs, glanced through the wire mesh window and then turned his back, leaving the mass murderer to be assaulted, Iverson didn’t call for help. He just let Connelly cram the page down his gullet, docile as a circus animal.

Once the man had choked it down, coughing wetly into his bound hands, Connelly eased back into his seat, the blood still throbbing in his temples. All at once he felt ridiculous. How many times had he advocated that the suffering of good people was all part of a greater plan, something too vast and complex for the human mind to comprehend? How many times had he trotted out the stories of Job and Noah as evidence? Thinking about it now, watching Iverson spit a clump of soggy paper onto the tiled floor, made him feel stupid and deceitful, as though he’d been knowingly propagating a lie.

Breathlessly, Iverson said, “Anything else?”

But Connelly just sat there motionless, staring at the scuffed-up tabletop, his face the color of raw meat. Overhead, the caged fluorescents buzzed like insects. In a near-whisper, he said, “No.”

Struggling up from the table, Iverson shuffled toward the door and called to the guard outside, “We’re done in here!”

By the end of the week, the news of La Virgen Llorona had made national headlines, the camcorder footage having been picked up by several major networks, and Connelly had turned down nearly a dozen interview offers with nationally syndicated outfits. It wasn’t just his adherence to the Guidebook’s directives on media engagement—“the Ordinary shall express no public judgment unless authorized by the archdiocese”—but also the fact that he had yet to stumble upon a plausible explanation for the statue’s tears. The sample he’d sent to the university lab in Lafayette had revealed very little, other than that the substance was chrism oil—olive oil mixed with balsam, used in confirmations. Available to anyone.

“You’re famous,” the waitress said when she arrived with his patty melt Friday evening, referring to the picture of him that had been aired on a talk show that morning, a headshot taken from the Shreveport diocese directory.

“I didn’t have anything to do with that,” he said. “They didn’t ask me for permission.”

“I take it the investigation isn’t going well?”

“I wouldn’t say that. There’s just nothing to report.”

“Is that a good thing or a bad thing?”

“Depends on what you believe, I guess.”

A sizable portion of his afternoon had been spent on the phone with the statue’s manufacturer, bouncing from one department to another until he managed to get ahold of a supervisor in the assembly plant. “And you say this thing is crying, is that right?” the man asked after Connelly had laid out the situation for him.

“In a manner of speaking, yes,” he replied.

“What’s that mean, ‘in a manner of speaking’?”

“There is oil coming from the eyes, and we’re not sure how. Could it have been trapped in the bronze?”

“Not likely. It would have been burned out in the heating process.”

“So, you don’t have any idea how this might be happening?”

The man let out a long breath, the sound of someone who had reached the end of his patience. And who could blame him? The whole thing was ludicrous, made even more so by the fact that divine intervention was becoming more plausible by the day. “I don’t know what to tell you, sir. But it sounds to me like someone’s jerking your chain.”

Now the waitress set the covered plate down on the table and said, “Why don’t you just break it open and look inside?”

“Can’t. There are rules.” Grabbing the Guidebook from the dresser, Connelly showed her the passage on page twenty-eight declaring that blessed objects were not to be wantonly destroyed in the course of inquiry, a violation of canonical law.

“Jeez, there’s a guidebook for this?” she scoffed, flipping through the volume, which was fringed with multicolored Post-it tabs.

“There’s a guidebook for everything.”

“Okay, so then a drill, right? You could just cover the hole with bronze epoxy. No wanton destruction.”

Connelly paused as he was lowering himself into his chair. “Bronze epoxy?”

“You don’t know about that?”

“No, I don’t.”

The woman seemed amused by this. “You can order it over the phone, bronze epoxy and pigment. Cost you maybe ten dollars.”

He sank into the chair as if he’d just been delivered life-changing news. Bronze epoxy. She made it sound so simple, so obvious. Like the answer to a child’s riddle. Yet, instead of the gratification he might have anticipated, all Connelly could think about was his conversation with Father Ortiz days earlier, the breeziness in his demeanor. What was it the man had said? Faith is reckless.

“How do you know about this?” he asked the woman.

She shrugged as if the subject were too boring to pursue. “My stepdad was a welder. I know more about metal than I probably should.”

“I wish you would have told me sooner.”

The woman rested her arms on the room service cart. “Honestly, I figured you already knew.”

In their final conversation, two days before Gary Iverson’s attack on the Fort Worth DMV, Connelly and Allison had argued over the phone about their father, an eighty-two-year-old widower whose decade-long battle with dementia had left him unable to recall the names of his five children, let alone drive or shop for himself. More than once he’d wandered away from his home and gotten lost, only to be picked up by a squad car and taken to the station for Allison to retrieve. As the only sibling who still resided in town, she had spent the past several years as his sole caretaker, hauling him all over town for doctors’ appointments, managing his arsenal of medications. Helping him to navigate his increasingly frequent bouts of senile paranoia.

And so, when Connelly, who had spent his share of time ministering in nursing homes, had suggested relocating him to an assisted living community, she’d balked: “I’m not going to just stick him in some home.” The way she’d said “home” made it sound like a slur.

“It wouldn’t be like that,” Connelly said. “There are excellent facilities where he can get the care he needs.”

“Meaning what, that I’m not providing it for him?”

“That’s not what I’m saying, Allie. All I mean is that you can’t do everything for him. You have your own life. There are specialists for this sort of thing.”

“Why do you always think you know what’s best for everybody?” Allison countered. “Like, we’re all just begging for your guidance, is that what you think?”

Connelly cleared his throat, trying to keep his voice free of irritation. He could appreciate his sister’s frustration; you put enough of yourself into something, it’s irksome when someone suggests that your efforts are unsustainable. Nonetheless, he only had so much patience, and perhaps it spoke to their bond that she knew exactly how to expend it. “Allie, my job is to guide people.”

“Sure, when they ask for it. But not everybody is looking to be saved. Believe it or not, some of us really are fine without your intervention.”

The conversation ended shortly thereafter, Connelly lying about needing to return some emails before bed. The next morning, he found a message from her on the machine, recorded close to midnight. From the crooked lilt in her voice, it was clear she’d had a few glasses of wine: “Hey, it’s me. I just wanted to tell you that I’m sorry I lost my temper. I know you’re just trying to help, and I appreciate it. I think we just have different ways of approaching problems, and that’s okay. Anyway, call me back when you get a chance. Love you.” Only later, after the funeral, would he consider that it was his own guilt that prevented him from calling back right away. Because it wasn’t her anger alone that had put him off—it was the fact that she’d been right about him.

Sitting across the desk from Father Ortiz, Connelly watched the portly priest finger his wooden cross in the absent manner of someone picking a scab. He described his conversation with the waitress, explaining how the two of them had spent fifteen minutes studying the three dozen photos, looking for some abnormality, something out of place. On some level, he’d hoped that she was mistaken, if only to justify the efforts he’d put into the inquiry thus far. And so, he was almost crestfallen when they finally spotted it on the top of the statue’s head, a minor shift in texture like a long-healed scar, made almost invisible by the shadows—what he could only assume to be a blotch of painted-over epoxy. When Connelly, suddenly overcome by the accumulated fatigue of the past several days, had said he hoped he wasn’t keeping the woman from her work, she’d scoffed. “Didn’t you notice this place is dead? This is like the most interesting thing I’ve done in weeks.”

From there, it wasn’t hard to deduce the rest, how the heat had evaporated the oil inside the figure, trapping it in the plaster, allowing it to seep out through the pair of slits the perpetrator had scratched into the undersides of the eyelids, which were too small and well-concealed to be seen by the camera but which Connelly had discovered this morning during a reexamination.

“You’d make a hell of a detective,” Father Ortiz commented when Connelly was finished walking him through the investigation.

“I’m just doing what they sent me to do.” Between his knees, Connelly twisted the Guidebook into a tight coil. Sweat pooled against his lower back. “You haven’t asked me who did it.”

“Do I even want to know?”

“I’m thinking Mrs. Alvarez.”

After the discovery, Connelly had gone back over the interview recordings. It wasn’t what the woman had said but how she’d said it: her defensiveness, it seemed too manufactured, a put-on. This became especially apparent near the end of the conversation, when Connelly had asked her why she thought God would want to save her church in particular, out of the countless struggling houses of worship around the globe. On the recording there was a long period of silence, during which the woman had glanced at Father Ortiz, who nodded for her to go on. At the time, Connelly had thought nothing of this, but upon hearing it again something had clicked, like tumblers in a lock falling into place. Squaring back her small shoulders as if preparing for a brawl, the woman had said decisively, “You’re wasting your time, Father Connelly. It is real. It is not a hoax.”

Now Father Ortiz laced his fingers behind his head. “That’s some accusation. Anna Lucia Alvarez is an old woman. I don’t see how it’s possible.”

“It’s not, unless she had help.”

For a long period, neither of them spoke. Connelly held the man’s eyes, a look that conveyed sympathy and recrimination at the same time. A tiny smirk played at the corners of Ortiz’s mouth, the red plums of his cheeks bulging. It wasn’t hard to see what made him such an effective cleric. Connelly had considered this late last night when, having resigned himself to sleeplessness, he’d climbed out of bed to stand at the hotel window, watching the traffic barrel down the cratered highway, past the dilapidated shops and restaurants, the vacant storefronts with their fractured panes. People headed to better venues. This wasn’t the kind of place you stayed if you had a choice—Father Ortiz understood this, just as he must have understood that faith was a shield: without it the world could crush you. Except, there was a reason the shield hadn’t been used in wartime since the Middle Ages, wasn’t there? It was too heavy and cumbersome, a liability on the battlefield.

“So, what now?” the man finally asked.

“Now I make my report to the archbishop.”

“Am I out of a job?”

“That’s not up to me.”

“Do you think I should be?”

“You’re asking the wrong guy.”

“No, I don’t think I am,” Father Ortiz said. He clasped his hands on the desk, a teacher having a heart-to-heart with a troubled student. “I think you understand what we’re trying to do here. And I think you can appreciate what will happen to these people if it’s taken away from them.”

Could he? It was true that Connelly had been almost sorry to have seen the patch of epoxy in the photograph. A part of him, he realized, had been holding out hope that the phenomenon was authentic, a sign from above. Now, all he could feel was the same frigid numbness he’d experienced after Allison’s burial, as though something precious had been taken from him by forces he was ill-equipped to confront. It was almost enough to make him divulge everything—his sister’s murder, the trial, tearing the page out of his Bible, his visit to Iverson in the detention center. Desperately, he wanted to unburden himself of it all, to unload everything he’d been lugging around this past year, and he could tell from the way the father was looking at him, like a man who knew all too well the value of confession, that he was ready to accept it.

But no, Connelly couldn’t bring himself to confess, just like he hadn’t been able to forgive his sister’s murderer, because maybe not every resolution deserved to be celebrated. Some questions, it turned out, really were better left unanswered.

Instead, he muttered his thanks to Father Ortiz for his hospitality this past week, to which the man gave a knowing nod but said nothing, and then Connelly drifted into the sanctuary, where La Virgen Llorona loomed over the throng of worshippers, a gracious overseer. He shouldered his way through the bodies, issuing soft apologies each time he stepped on a toe or bumped an elbow, until he found himself standing in front of the statue, alongside folks curled up in praise like shuddering fists or gazing up at the Virgin with the open-mouthed wonder of children, the heaps of knickknacks on the floor resembling a street vendor’s inventory.

It was as he was kneeling to deposit his rumpled copy of the Guidebook—the only thing he had left to offer now that he had run out prayers—that he heard the volume in the room plummet, the same kind of quiet that descends over a theater before a performance. Thick and full of expectation. Peering around behind him, Connelly saw that the roomful of disciples had turned its attention to him, their faces alight as they waited for his verdict. Slowly, he came to his feet, and with the same trepidation he always felt before a homily, he searched his mind for something to satisfy them, something that felt like it might be true.