The High Shelf

By Dawnie Walton

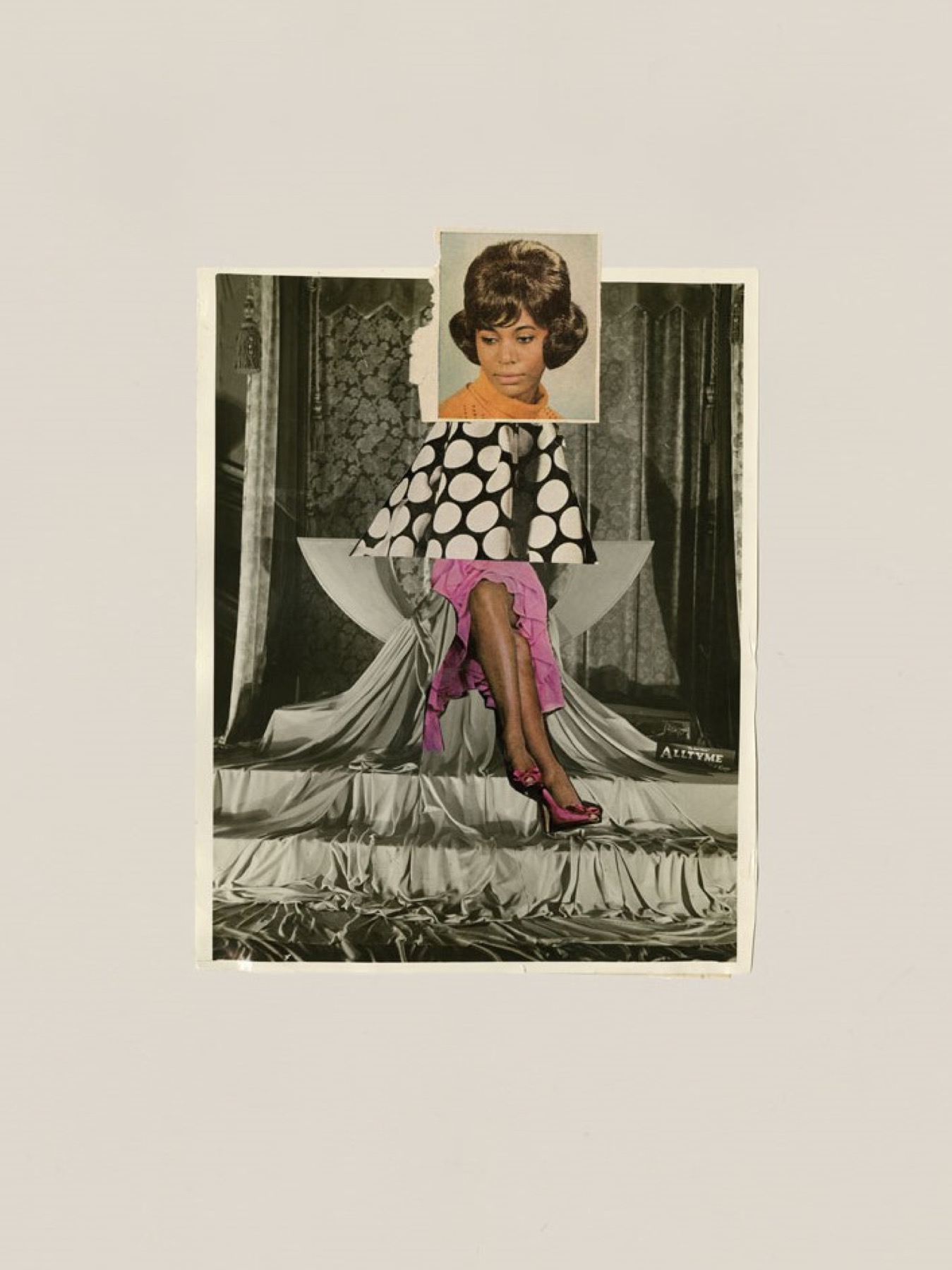

Dots (detail), 2016, found photograph and collage on paper, by Lorna Simpson. © The artist. Courtesy the artist and Hauser & Wirth

Not till after she’s had her dinner, braided down her hair, and slipped on her nightgown does Willa Mae get up the gumption.

In her living room, reclined to the middle stop of her late husband’s tan-leather La-Z-Boy, she stares at the episode of Family Feud blaring from the TV but sees only how her stunt will play out, step by step. Her children do not like such foolishness, she knows. But God forgive her, she does not care.

She wriggles to sitting position. Her feet find her fuzzy slippers; her hand, the remote control. She shuts off Steve Harvey and the old house plunges into a foreboding silence. But then the idea—exquisite, building, like the tickle of a sneeze—rushes in to thrill her. Yes, she thinks, I’mma do this. She pads down the hallway to her bedroom, her slippers whispering shush-shush across the plush mauve pile.

There, draped down the cold side of the bed, is the outfit she’s picked special to visit with her neighbor tomorrow. The floral blouse she’s already pressed and tucked inside a black cardigan, and it goes real nice with the bottoms that look like dark blue jeans but actually aren’t. Knee-high nude stockings poke out the legs of those. She’s even got jewelry to “elevate the look,” as she’s heard those TV stylists say: a long, silver chain of oblong links running inside the collar of the blouse and a thick bangle of hammered silver cinching the cardigan’s right cuff. In the lamplight, Willa Mae gazes at what she’s managed to put together. She had other options once, nicer pieces, but this is the best of what the children have allowed her to keep. And she has laid the clothes out with great intention, as if readying them for her spirit to jump in.

But then—Lord have mercy, then—she lifts the bedspread to reveal where the clodhoppers lurk. She tilts her head back and squints, asking herself if maybe, just maybe, she’s been too harsh. But no; the clash is more obvious than before. So ugly they’d give poor Doris Cleghorne another stroke. Willa Mae clenches her mouth, convinced.

She’ll walk barefoot across McMillan Street, she vows, before she wears those damn shoes again.

On a Sunday last December, Willa Mae had a fall. Just one hard tumble in eighty-four years, but it was enough to put the children on her case. She’d been fully dressed for church when it happened. Wearing the spectator pumps she’d snagged in the Black Friday blockbuster deal—the heel a little higher than it had looked on the TV, she had to admit, but still thick, and not much more than an inch and a half. She’d been coming through the living room to let Junior know that she was ready, that he could go on and warm up the van, when she tripped on a shipment of kitchen wares she hadn’t had a chance to put away yet. Junior had sprung from the couch, trying to catch her arm, but her son was getting up in age too, his reflexes dull. So down Willa Mae went. In the end a top right molar had to be pulled; it was cracked clear to the pulp. But the fall could have been worse than a scrape on the knee and her teeth crunching together. Her old bones had held up fine, vibrating just slightly as she hit the floor. The carpet had been a good investment after all. She’d thought of Senior then, how even in death he was telling her so, and despite herself, she'd laughed and laughed.

But her daughter, Carole, didn’t see the humor. “You got too much junk, Mama,” she’d fussed on the phone that night, after Junior brought Willa Mae home from the dentist. “How are you supposed to get around, the house all junky like that?”

“Don’t you worry ’bout my house,” Willa Mae had mumbled, her mouth still numb from the anesthetic. “My house been my house since before y’all hit the scene.”

But Willa Mae should have known the battle wouldn’t end there. Her youngest was stubborn, and more than a little sneaky. A couple days later Carole had called back, talking about Christmas. Talking about how she and Junior had discussed it and they would handle the details. Talking about how their first year with Senior gone, Willa Mae shouldn’t have to worry about a thing, except relaxing and enjoying the day. “Fine,” Willa Mae had said, tonguing the new hole in the top of her jaw. But only because she was curious, and had finished her holiday shopping already.

Still, she’d felt anxious that bright Christmas Day, sitting on her front porch and watching for Carole to arrive with the food. This was the first time in ages she hadn’t cooked. If some disaster happened over to Carole’s house—if the girl dried out the bird or tipped too much vinegar into the collards—Willa Mae had nothing in the way of a spread. Not one egg to devil, not even a sweet potato pie. Only the From Santa with Soul compilation CD she’d rush-ordered with twelve minutes left on the deal countdown clock. For the third time, after the Temptations and Donny Hathaway, her little pink boom box cycled back around to her favorite, Nat King Cole. Waiting, watching, Willa Mae let his golden croon soothe her. The rails of her rocking chair bumped reassuringly against the orange extension cord she’d attached to the boom box, to siphon juice from the house.

Across the street, Doris Cleghorne, who had lived in the yellow bungalow kitty-corner from Willa Mae for what felt sometimes like a thousand years, was taking out the recycling. She carried two big clear bags bulging with colorful wrapping paper in one hand and pinched a lit cigarette in the other. Doris’s brood had come to see her the previous night, to get their Christmas Eve plates and exchange presents, and there had been so many relations they’d turned Doris’s front yard into a parking lot. Some of the young ones had rolled down the block with their stereos pumping, the heavy bass making Willa Mae’s windows judder. She’d had to get up from her Law & Order to peek out the blinds and see what in the devil was going on. She’d peered out at her own struggling grass, which Junior had been fighting so hard to keep healthy since Senior had passed, and she’d glared in the direction of those rowdy Cleghornes ambushing Doris’s lawn with their rattling heaps. Standing in her nightgown, clutching the receiver of her cordless phone, wishing for all the world she had the powers to conjure up a fence, Willa Mae had whispered to herself, with an ugliness that surprised her: I wish somebody WOULD.

Christmas Day, though, called for more charitable thoughts. For loving thy neighbor. And so on her front porch she hummed along with old Nat, whose holiday classic she’d always loved (even though Jack Frost rarely found his way to Florida), and when her favorite part hit, Willa Mae sang out, loud enough for even a Cleghorne to appreciate: “And folks dressed up like Eskimooos . . .”

Doris’s head snapped up then. She waved the hand with the lit cigarette, then took a long drag. “Well, ain’t you a pretty picture!” she hollered, in that rusty voice of hers.

Willa Mae smiled and waved back, the bangles on her wrists tinkling like silver bells. Her neighbor, she saw, was wearing her typical tracksuit and tennis shoes. Doris seemed to have an endless supply of each item, mixing them up to make hundreds of versions of the same uniform. Mainly these outfits were differentiated by color, logo, and whatever garish thing happened to be emblazoned across the jacket’s back. The roaring mascot of the Jacksonville Jaguars, say, or a glittery heart with an arrow shot through it, or, if the suit was a gift from her grandchildren, flaking white letters running across cheap custom-screened poly. (“O.G. SAVAGE!!” Whatever that meant.) Willa Mae had to admit that the sporty look was a fine one for Doris, who in her prime had been nearly six feet tall and broad in the shoulders—rather mannish, Willa Mae sometimes secretly thought. But for Christmas, Doris had thrown in something unexpected, something new: giant sunglasses that ate her eyebrows and bit into her cheeks. Bright rays glinted off the rims.

“Had a house full last night, I see,” Willa Mae said, and leaned down to pause the music.

“Ms. Washington, I swear they ’bout wore me out.” Doris tossed the bags into her blue bin, snuffed the cigarette under her sneaker, and stepped down off her curb, looking both ways before cutting over to Willa Mae’s side of McMillan. “Ain’t got a leftover left.”

Willa Mae chuckled as her neighbor approached. No matter how many times she’d told the woman to call her by her Christian name, Doris just wouldn’t do it. (And Doris wasn’t but nine years younger—that was nothing, when they were both so old.)

Now Doris was standing at the foot of Willa Mae’s front steps, and with the hand that had been holding the cigarette she pushed the sunglasses up her nose dramatically. Willa Mae was no ninny; she knew what Doris was attempting to do. She could see very well, now, the twinkling doodads—rhinestones? cubic zirconia?—embedded around the lenses of the sunglasses. Could see very well that the lenses, tinged pink, gave Doris’s skin a rosy glow.

Yes, Willa Mae understood that her neighbor loved these glasses. But she also could see that drawing attention was an awkward pose for a woman like Doris. A woman like Doris was the kind Willa Mae’s mother had once admonished her never to be: one who was “afraid of her own beauty.” Who chose comfort and convenience and lost all femininity in the trade. (“Be like that,” Willa Mae’s mother had once warned her when she was fourteen, gesturing toward a woman shopping at the farmer’s market while daring to wear a head scarf, “and you’ll never keep a man.”)

Finally, Doris dropped that hand, that unnatural display, and made an airy gesture toward Willa Mae. “Ooh, looka here!” she said. “You got you a new do for the holiday, didn’t you?”

And though Willa Mae could have resisted showing off, resisted the kind of grotesque vanity that had shocked her while watching various TV programs about housewives, she could not help but preen in her newest luxury. The wig had come in the last shipment, along with the CD, and when Willa Mae had first pulled open the bag that held her new hair, she had felt electrified, despite a wafting, plasticky smell. She could air the wig out on her Styrofoam stand, she knew, or spritz the air around it with Febreze. The important thing was that the style was gorgeous. A chic, close-cropped cap of feathered layers. Silky through the fingers, sheeny as a baby doll’s. It made her feel better over losing that tooth. And what was the harm in that?

“Got it off my QVC,” she said, peering down at Doris. “They named it the Kiki, but I call her Diahann—after Ms. Carroll. May she rest.”

“What a glamorous woman she was,” Doris said.

“And a head for business too,” Willa Mae allowed. “Sold her own wig line once, you know.”

Doris flicked at the concrete banister that framed up the left side of Willa Mae’s steps, and took her regular perch. “I tell you, ever since Finesse messed me up I sure don’t know what to do with this mop of mine.”

“Well,” Willa Mae sighed. Doris had many excuses for why her hair always looked a mess, but the one she used most often had to do with the time, nearly five years ago, that her nephew, then in cosmetology school, chemically burned her scalp while trying to apply a relaxer. Willa Mae had heard this story too many times in the few months she and Doris had become friendlier, but it was awful tragic. Willa Mae could see it was damaged, so skimpy that even the child’s barrette Doris wore to fasten it at the kitchen was constantly threatening to fall off. Even if she were to get a wig, what on earth would it hook on to? Thump thump thump, went Willa Mae’s rocking chair, and something in the rhythm reminded her to have a heart.

“Them sunglasses real nice on you, Doris,” she blurted. “Real nice.”

“Oh, you like these?” Doris beamed. “I thought they were too young, but I guess they look all right.” She took them off, wiped the lenses with a cloth she pulled from some mystery zippered part of the tracksuit, slid them back on. “You’ll never guess who they from.”

“Who?”

“Maurice’s new girlfriend,” Doris said. “He brought her home this year from New York. Such a sweet little thing . . . Maybe that boy will finally settle down.”

“Mmm-hmmm, hope so. You raised him up right. I bet he just waiting for the right one.” Thump thump thump. “Would take a load off your mind, I know it.”

They went quiet and thoughtful then, as they usually did when the subject involved Doris’s youngest, or lotharios in general. So Willa Mae hit play on the Christmas CD. Little Michael Jackson chirped about mommy kissing Santa Claus. Doris gently kicked the back of her tennis shoes against the concrete, in time with the jangling music, and up on her porch Willa Mae rocked to match.

For nearly nine months now, since Senior had died, the two of them—the last owners standing in a neighborhood overrun by in-and-out renters—would sit like this in nice weather. Usually when the sun was sinking, and always on Willa Mae’s side of the street. Usually not expecting much of each other, Willa Mae thought, just the comfort of company, of another woman’s undemanding presence. Maybe a compliment here and there. Usually they’d run out of things to say, and then they’d sit content as they watched the sky go orange, then pink, then purple. Usually they’d go back inside their empty houses when the street lights cut on. But this was a blazing-bright Christmas Day, built up to be special. Unusual.

They turned toward the hiss of car tires rounding the block: finally, Carole. As the Acura came to a stop in front of the house, Doris rose, swatted at her nylon-covered backside, and fluttered a hand in greeting. Willa Mae, her heart surging, gripped the sides of the rocking chair and stood up too. She smoothed the front of her red mock-turtleneck sweater dress, slipped into her suede green kitten heels.

Carole popped out the coupe and opened the trunk. “I got this, Mama, you sit back down,” she ordered. But Willa Mae stayed in position at the edge of the steps, her hands outstretched, ready to receive. Her daughter sounded tired, she thought, but still looked very nice in her leopard-print cowl-neck blouse and black jeans, her leather ankle booties with the dancing fringe. And her lips were painted that pretty, rich burgundy . . . Oh, how Willa Mae loved that color! It was the same flattering shade Carole had worn for her official Wendy’s management portrait, hanging on the wall of her restaurant. After Senior retired, he would carry Willa Mae across town to Carole’s location every Saturday afternoon, dropping her off while he went to play whist with his buddies from the VFW (or so he said). And because Carole would be busy back in the kitchen managing her knucklehead staff, Willa Mae would sit as close to her daughter’s 8x10 as possible while enjoying her hamburger lunch. Alone at a little table for two, Willa Mae would use a plastic knife to cut her single-with-cheese in half, and she’d shake out her French fries on the tray’s paper liner, and squeeze out a teeny pool of ketchup, and wish her sugar was low enough to risk the Frosty. But those days were gone. She didn’t have anybody to drive her regular to the Wendy’s now, so she could sit and enjoy the portrait. Now she settled for the wallet-size version of Carole’s pretty picture, and when her Kenneth Cole Reaction trifold had arrived in the mailbox, that photo was the first thing she’d slid behind the wallet’s clear plastic pane. She’d show it off to people when Junior came over on Tuesdays to run her on errands. Her Carole was the only Black female franchisee in the whole county, she’d tell bank tellers, the nurses at the doctor’s office, the cashiers at Winn-Dixie. And not a one of them who saw that picture could believe her daughter was anywhere close to fifty-two.

“Ms. Cleghorne, Merry Christmas!” Carole said as she pulled from the trunk four covered roasting pans and placed them on the Acura’s roof. And Willa Mae felt that old dyspepsia, bubbling up from somewhere deep, as she watched her daughter step into Doris’s embrace. The past was the past—Willa Mae knew that—but she couldn’t help but flash back to the time when Carole was eleven and had asked Doris to be the subject of a school report. What was it like to have a job as a bookkeeper?, Carole had wanted to know. As if Willa Mae had nothing useful at all to say about keeping things in running order.

“Sharp shades you got there,” Carole was telling Doris now.

“Thank you, baby. And Merry Christmas to you, too.” Doris made a move to go, her tracksuit swishing. She looked back up to Willa Mae on the porch. “All right now, Ms. Washington,” she said, with a strange little salute. “You all have a good one.”

Willa Mae scurried to open the screen door for her daughter, who was lugging in the biggest of the pans. It was either the turkey or the ham, judging from the way the foil crested, mountainous, but Willa Mae couldn’t smell a thing as Carole bent down to kiss her cheek on the way inside. That meat stone cold, Willa Mae predicted. She’d have to turn her oven to 350°, dribble a little water in the roasting pan, wrestle that turkey or ham or whatever it was inside to let it warm up nice and slow under the foil—just enough so it didn’t dry out.

But just as she was about to drag the boom box inside and get to work, she caught the sight of Santa Claus—the one stitched onto Doris’s back—in full retreat, his jolly face at odds with the slump of shoulders hanging over him. Maybe Willa Mae was imagining it, or maybe she had just learned a lot from the body-language episode of The Talk, but she sensed a sorrow emanating off Doris. And why wouldn’t that be the case, on a Christmas Day? Doris had been living on her own for so many Christmases now, and Willa Mae had just joined the club herself. Having endured her first Christmas Eve in solitude, having felt irrationally angry watching the Cleghornes be merry in their gathering across the street, Willa Mae had wondered: Did she still have call to be so cautious around Doris, after all these years? It was true that she hadn’t invited Doris past the front porch since 1980; neither had Doris ever asked to come in. It was also true they each had their reasons for that. But they both had survived, and the reasons were dead. This could be the year, Willa Mae decided, that envy would fly free of her spirit. That she would rejoice and be generous.

She came back out to the edge of the stoop.

“Doris!” she shouted, and waited for her neighbor to turn back around. “I’m sure we got a extra plate over here. If you wanna.”

What happened was that Carole asked for her wallet and called, right then, to cancel the credit cards.

In her bedroom, Willa Mae takes everything that’s loose off the top of the nightstand—the clock, her blood pressure pills, her dog-eared mystery novel and the small metal lamp by which she reads it. She carries the items out into the hallway, then kicks off her slippers and leaves them there. (She’d never tell her children this, but she actually does feel stronger, more rooted, barefoot.) She walks back around to her side of the bed and, finally, she’s ready to try.

At first she tugs the nightstand from the top, one hand gripping either side, but her arms are weak and the thing won’t budge. It’s more solid than any of the wicker-bottomed dining chairs in the house, and squat enough for her to clamber up—that’s why she’s built her plan around it. But it’s rosewood, which means it’s surprisingly heavy. She’s afraid she’ll lose her balance this way. Fall and bruise her tailbone bad. And to reach the closet she’s got to lug it far, all the way around the bed and across the expanse of carpet.

She stops and thinks. Just to see, she pushes against the wood instead, pressing into the side with her good hip, and although she feels the nightstand tilt slightly, bowing toward the bedroom’s back wall, it’s not moving in the direction she needs it to go. She needs pull, not push.

Willa Mae crosses her arms, twiggy underneath the thin cotton nightgown. All these decades in this house, and she can’t seem to remember ever having moved any furniture. But somebody must have done it! Senior had the wall-to-wall installed sometime in the late ’80s. They’d had a good amount of money saved, Senior and by extension Willa Mae, for the children. But when it had finally accumulated, Junior was already off and working, his summer job assisting a contractor having transitioned into something steady after high school, and when the time came for Carole to leave home she’d told them with proud, gleaming eyes that they didn’t need to worry. She had it handled—a full ride to Bethune-Cookman and a cashier’s job at Wendy’s besides. “Why don’t you take that money you saved and go on a trip?” she’d suggested to Senior as he scanned the scholarship letter for himself, his own eyes beginning to water. “The Bahamas or somewhere. Daddy, you’ve just been working so hard.”

Willa Mae had begun to hope, then. Could she and Senior really be the kind of couple to go on a vacation? Could she wake up and be spared, for once, the drudgery of making Senior’s same old breakfast? Could she pretend to be someone else, another woman? Better yet, could they simply see each other as they once had been, before the children—could he be her Lawrence again, and could she be his Lil’ Bit? Scrambling his eggs and charring his red-hot one morning, Willa Mae considered their Carole, how different and exciting her options were turning out to be, and she thought, Maybe. For a few weeks she began to hum along with that catchy cruise-ship commercial, the one with Kathie Lee Gifford twirling on the deck, checking out the buffet, singing in a strapless white evening gown about how her friends would never believe it.

But in the end, Senior had decided to use the money on home improvement. That was the most sensible thing, he’d decided, and as he got older he was sick of feeling even the slightest bit of cold in winter, on the handful of days the temperature dipped below forty. Besides, he’d said, Junior would be giving them grandbabies soon, little ones who’d be running around, slipping and sliding everywhere, and this had made Willa Mae remember the days of wielding tweezers, plucking splinters out of her children’s feet as they bucked and howled.

This was the way Senior had always gotten Willa Mae to give up: harped on what was best for everybody else around her. And so she’d stopped talking about the cruise soon enough, stopped hoping. Senior went to the hardware store one day and brought home a big book of textured swatches, and that was that. At least he’d let Willa Mae choose the color.

In fact, with the budget her husband meted out for such things, she had chosen everything for their house on McMillan Street, from the lavender fleur-de-lis wallpaper in the bathroom right down to the pronged plastic doohickies for eating corn on the cob. In that way, the house and all its treasures were hers. All of them investment pieces, some more costly than others. The nightstand was actually an end table she’d acquired from remnant stock at the electric company, back when the downtown headquarters was under renovation and the bosses were offering employees a discount on the old furniture. When Senior had said he’d take her for a look around, Willa Mae armored herself, putting on her most flattering fit-and-flare dress and, in the privacy of the bathroom, practicing how to hold her head high. Her husband had stopped working out in the field by that time, his physique softened and long past the dangerous days of scurrying up utility poles, and yet imagining him in an office made Willa Mae even more afraid. She had prepared herself to see the exact place her husband worked, had prepared to cross paths with secretaries and interns and perhaps even a few very modern women. But she never did see his office that day. Instead Senior guided their Cadillac to an adjacent loading dock where the furniture for sale had been moved out and stacked. Willa Mae had felt so silly and siddity then, poking around the dusty area in her very best dress while Senior waited in the idling car. The nasty rednecks the electric company had hired as haulers pestered her, rushed her: You buying something or not, lady? Years later, she’d learn from watching Antiques Roadshow that the table she’d hurriedly chosen that day was of a style called mid-century modern, and then Junior, while doing a renovation for some rich white folks across the river, had figured out what grain of wood it was. “It could be valuable,” she’d told Senior. But he mostly ignored her prattling about details.

Sizing up the table now, a widow nearly thirty years later, Willa Mae cares only about portability, sturdiness. And she needs a different angle of approach. She hitches up the hem of her nightgown and eases down to the floor, slowly, slowly down until she is on hands and knees, the thin white cotton gown billowing around her, and she can get a good look at the bottom of the nightstand. She sees the problem now: Its short legs, round and tapered, are sunk into stubborn divots they’ve drilled into the carpet. She grabs on to one, inhales deeply, and, on the exhale, the way the people do on the yoga, she moves—pulls the nightstand toward her. The hulk jerks forward. “Now we talking!” she says out loud.

Still, there’s a long way to the closet on the other side of the room. Willa Mae will need a more comfortable position than this—her knees can’t take much more direct pressure. She shifts onto her bottom and sticks her legs underneath the table, then reaches forward to take hold of the front legs in her hands. Bit by bit, scooching backward on her butt like a nasty old dog, she breathes and pulls, breathes and pulls, managing to drag the nightstand farther. Every couple minutes she pauses to rest, but when she makes it to the foot of the bed and catches a glimpse of the clodhoppers, dull and gray and tough as two slabs of rotten meat, the anger prods her on. Her children have some nerve, deciding that they know what’s best.

Because I’M the mama, she stews. I’M the mama.

The Christmas that Doris Cleghorne came past the porch, Carole seemed agitated. She was fussing about Willa Mae’s new pinecone-and-poinsettia centerpiece—“Beautiful!” Doris had rasped—because its large size made setting the dining table difficult. “Oh, now you wanna eat at the formal table?” Willa Mae had teased, tickled by her daughter’s efforts at domesticity, but Carole had only rolled her eyes and then poked around in the closets, trying to find enough space to put away the centerpiece. Eventually she just stuck it atop a big unopened box sitting in the corner of the living room. (“Couple sets of linens in there,” Willa Mae whispered to Doris. “Egyptian cotton. Got a good deal on ’em, too.”)

After a while the house started to fill: Carole’s second husband, Harris, arrived, and then a few of the cousins, and finally, with dinner threatening to go cold all over again, Junior came straggling in. The boy needed a haircut—his graying ’fro was mushrooming out the sides of his ball cap—but, as promised, he’d brought along a van load of the babies. Willa Mae’s great-grands trooped in the door behind him, each one hugging a bag of ice or a case of soda or a store-bought sweet. Brand names popped off their gleaming new clothes. The children’s eyes lit up at the sight of the gifts waiting for them underneath Willa Mae’s tree, an assortment of action figures and puzzles and games that she had been ordering and saving for them, but they managed to keep their cool. Apparently under orders from Junior, they’d stopped by the La-Z-Boy first to kiss Willa Mae on the cheek. And then she’d made them go over to the love seat and say hello to Doris Cleghorne, whose novelty sunglasses now rested atop her head.

“Santa was good to you?” Doris asked each baby, delighted, holding them by their precious little arms. Each one nodded shyly, politely, and Willa Mae swelled with pride.

“Go put that stuff down in the kitchen,” she told them, “and see what Santa left for you here.”

Doris laughed as they skittered off. “I imagine their mamas and daddies are getting in a good nap about now.”

“Probably been up since the crack of dawn,” Willa Mae agreed, and thought of her grandchildren, back when they were the ones underfoot, and before them, Junior and Carole. Those were the years she’d bought the boys green army men and Power Rangers, the girls Black Barbies and Beanie Babies . . . According to the gospel on QVC, Willa Mae had been tickled to learn, the kids were back to everything Pokémon now. Lord. She certainly had been blessed with a decent and long life—long enough to see how things could come around again.

But funny, she mused, that Senior had to die before the old house could see this much life return. From the island of the recliner she looked around at the bustle surrounding her: Carole and Harris setting up a card table and folding chairs for the babies to sit and eat; Junior, flipping through channels to find the game; the older kids, huddling over their cell phones and taking turns dancing some convoluted routine; and the younger ones, tearing manically through wrapping paper. She caught eyes with Doris, who had the good manners to eat not one but two plates. Who smiled and nodded back, just the slightest bit.

Willa Mae couldn’t remember the last time she’d felt so satisfied. If her days could be more like this, she thought, more filled with family—and, yes, perhaps a good friend—so what if Carole used Swiss instead of sharp cheddar in the macaroni? So what if the glaze for the ham had a funny aftertaste? Willa Mae didn’t have much of an appetite anyway, these days.

And so what, she reasoned later, if she loathed the one gift her children had conspired to give her? So what if Doris had made a sympathetic face when Willa Mae had opened the box, and again when Carole had announced that even the most stylish elderly women gave them five-star reviews on the internet? So what if one of the toddling great-grands had seen the shoes lying open under the tree and thought they were toys (some kind of musical boats, maybe?), and then pressed frantically at the neon-pink lightning bolts stitched across the toes, and then tore at the Velcro fasteners with his fat fists until the resulting racket gave Willa Mae a headache? The noise of resistance, of rice scorching in the pot, of static on the TV when a storm knocked the cable out—so what, so what, so what?

The bargain was irresistible. She could take an extra aspirin, she could wear the orthopedics every once in a while. She could be grateful, so grateful, if only more days could be just like this.

But Christmas was special, and then it was over. That was its trick. Willa Mae had tried to show good faith approaching the new year. Only because she knew it would make the children happy, stop them from worrying about her breaking her neck, she’d worn the clodhoppers a few times when they dropped by. At first with high hopes, imagining Junior and Carole so pleased that they’d start spending more time with her, or take her to the new outdoor mall on the Southside for lunch, or bring the great-grands to come and play in the yard. But nothing changed. Once, Junior picked her up for Tuesday errands and Willa Mae even wore the clodhoppers outside, hoping he’d notice. She honestly wondered how he couldn’t—it was like she was walking in potato sacks stuffed with memory foam. It was like pigs were flying and hell was freezing and Willa Mae Washington, to her shock and horror, had been caught dead. That is how it had felt for her, to put on those shoes. But when Junior dropped Willa Mae home and brought in the last of the groceries, he just kissed her on the cheek, took out the garbage from the kitchen can, and left. Same as always.

So Willa Mae went back to her own routines too, and the clodhoppers went back in their box underneath the bed. Even on her front porch she was impeccable—from across the street, more “beautifuls” poured out of Doris’s mouth (along with that nasty cigarette smoke she made sure to exhale before strolling over). Her neighbor, in fact, had seemed relieved by Willa Mae’s return to form. She’d even taken to teasing Willa Mae about the orthopedics, joking she’d had a nightmare they’d come to life one night and rolled over the stoop like a tank. “Bury ’em deep, Ms. Washington,” Doris had cackled, “else they gon’ come kill you.” The two of them had laughed until they’d cried. And nearly every day Willa Mae kept on ordering: T-straps and peep toes, jewelry, handbags, hats—all the things that made her feel dignified and delighted, and all of it, she was told, at extraordinary prices. The shipments came at least four times a week. She became friendly with the delivery man, who chatted with her sometimes, and brought inside the bigger boxes, and filled the rooms in Willa Mae’s house with joy.

Now that, it seemed, her children noticed.

What happened was that Junior picked her up after church one long communion Sunday, and as he pulled up to the house, Willa Mae saw Carole’s Acura and some other trucks parked outside. “Now calm down,” her son had said, cryptic, but Willa Mae’s heart was leaping. She was turning eighty-five years old in one week. She was picturing an angel food cake with strawberries, the great-grands in those paper cone hats. She was straightening Diahann, nearly hopping out the van, bracing for the “SURPRISE!” as she turned the doorknob.

What happened was that inside, she found Carole and Harris and three women she didn’t recognize rummaging through her things. Filling moving boxes and trash bags, keeping lists on yellow legal pads. What happened was that Carole was using business-y words like “reorient” and “declutter,” but Junior—her unflappable, easygoing boy—he had been the one to shock her the most, his voice shaking as he sat her down at the dining-room table and asked her how much of the benefit money she’d burned, ordering this hoard of junk off the QVC. What happened was that Willa Mae said she didn’t know, exactly, but she didn’t like his tone at all. What happened was that Carole asked for her wallet and called, right then, to cancel the credit cards. What happened was that she felt humiliated in front of strangers inside her own home, but for some reason Carole was the one to start crying.

But the strangers were nice. Professionals of some sort. Maids? Movers? One of the women took Willa Mae—exhausted, defeated, still in her church clothes—through every room, and had her choose one of each thing. One oven mitt, one towel set, one cardigan, one wig, one pair of dress shoes . . . Willa Mae couldn’t think straight. Her only decision was to take the Mary Janes off her feet and give them up. Instead, she whispered, she would keep the newest shoebox, even though it had not even been opened. She couldn’t remember what style the shoes inside were, or what color—she’d only wanted something new to open for her birthday. Then she watched as another of the strangers, a thick girl wearing an elaborate toolbelt, put together a wire shelving unit for her bedroom closet and stuck Willa Mae’s choice on the highest shelf.

“If you need to get something down from here,” Junior said, “call me or Carole to come help you.”

And when the dusk came down and the strangers loaded up their trucks to drive her things away, Willa Mae watched through the blinds and saw Doris Cleghorne. Standing on the curb, smoking her cigarette, shaking her head.

She’s left the cordless phone in the living room—but even if it was within reach who could she call, to catch her indecent like this?

Always with the cigarettes. Terrible addiction, Willa Mae had often thought whenever she’d spy her neighbor lighting up. Cancer sticks.

But it wasn’t cancer that ailed Doris now. Two weeks ago—four months, that is, since the Christmas Day they’d shared together—Doris had suffered a massive stroke.

Thing was, Willa Mae would never have known. After her humiliation, after the clodhoppers became the only real shoes within safe reach, Willa Mae had quarantined herself inside the house. Barely getting out of her nightgown before it was time to put it on again. Sometimes she went to the blinds to see if maybe she’d catch a glimpse of Doris outside. She did miss their little dusk chats, but the truth was, she wasn’t ready to do anything about it. Then one night the siren and flashing lights of an ambulance coming down McMillan startled Willa Mae awake.

The next day, she saw Doris’s youngest boy, Maurice, pull up across the street, an overnight bag slung over his shoulder, and she hustled out onto the porch barefoot to find out what was going on. Doris, he said, had managed to get to the phone to call 9-1-1. And as Willa Mae looked into the worried face of the poor boy who’d grown up across the street, she realized that she didn’t even have his mother’s telephone number.

She felt so ashamed over that.

She felt ashamed, too, over the one other time she’d invited Doris Cleghorne past the front porch. It was a Sunday in 1980, not long after Doris and her kids first moved into the yellow bungalow with no husband or father in sight. Willa Mae was forty-four; Doris, deep into her thirties.

The kids had made fast friends, of course, slipping in and out of each other’s houses. At first Willa Mae was concerned—what would her church folks say about the influence of rowdy boys whose mother had perhaps been around the block?—but then she reckoned that whatever had happened in Doris’s past, the kids were innocent (and, as it turned out, Doris didn’t go to church anyway). Willa Mae gathered snippets about the new neighbor from what the children told her: She worked for a Black dentist, keeping his records and books; they’d once had a stepfather who could play the guitar; she smoked Virginia Slims; she let the kids eat SpaghettiOs and sugar cereal. Every afternoon, once Junior and Carole had made it safely home from school, Willa Mae would peer out the blinds to watch little Maurice fumble with his front-door key across the street. She’d picture him dumping congealed noodles into a pot while the kitchen went dark, while waiting for his mother to get home, and she’d think, How sad.

But in the mornings, the families’ schedules coincided. All the kids ganged up for the walk to the school bus at around the same time that Doris Cleghorne (then a devotee of sleeveless blouses with pleated trousers) was rushing out the door and into her puttering Datsun. The year that Carole was eleven—the year of the school report—Willa Mae was mortified when her daughter raced across the street to catch Doris before work. Willa Mae had told her daughter a thousand times: Ms. Cleghorne was probably too busy to help with another child’s assignments. But Carole had always been stubborn, and more than a little sneaky. When she came back up on the porch to get her lunchbox from Willa Mae, she gloated, “She said she’d be honored to, if it can be on the weekend.”

When that Sunday rolled around, after the early church service Willa Mae threw together a box cake with lemon frosting and put out the good hand towels and touched up her lipstick and dusted and swept the living room, but what she wasn’t about to do was one more thing outside of the ordinary. She had jobs to do too, and Sunday afternoons were for laundry. When Doris and her brood arrived—the Cleghorne boys racing to the back room to roughhouse with Junior, Carole and Doris set up on the living room sofa with the cake and a pitcher of lemonade—Willa Mae excused herself, pulled the laundry from the washing machine off the kitchen, and went out the door that led from the kitchen into the backyard to hang the clothes on the line. She hadn’t given much thought to Senior, who was generally a silent, napping lump in the living room on Sundays, sprawled out in the recliner snoozing between sports matches, worn out from his week’s hard work.

And so Willa Mae had been shocked when she came back inside the house—the empty basket tucked under her arm, tiptoeing so as not to disturb her daughter’s big interview—and heard her husband’s low voice. In an instant she had known that Carole was no longer in the room, and the knowledge of that stopped her cold. Willa Mae held her breath and listened.

“. . . need any help over there,” Senior was saying, “a pair of strong hands or anything like that, you just let me know.”

There was silence, and then Doris’s murmur: “I manage fine on my own, thank you.”

“Oh, I’m sure you do. You just take care of everything, don’t you? I see how you bustle around.” More silence. “But I imagine that must be exhausting. I keep a good scotch, you know, and if you ever wanted to have a glass or two, a cigarette, a friend, I wouldn’t mind . . .”

“Mr. Washington,” Doris had interrupted, crisply enunciating every syllable of the name. “I’m sure your beautiful wife is just as exhausted as me, with two kids of her own and you to keep an eye on, too.”

Senior laughed. Willa Mae’s heart was in her throat.

Carole’s footsteps pounded down the hall. The floors, still hardwood back then. “Found one!” Willa Mae heard her daughter say, then the crunch of a cassette into the portable tape player, and the squeak of Senior getting up from the recliner and heading toward the kitchen. She fixed her face as he passed her to get to the refrigerator, and pretended she had just now come in from outside. She stood tall, gripped the laundry basket, and walked back into the living room. Playing her role.

Over the rest of their growing-up years, the children still raced back and forth across McMillan, in and out of each other’s houses. But from that day forward, when their mothers’ routines aligned, Doris would only wave, maybe shout a how-do, and go about her business. She never said a word about what happened in the living room that day, either to Willa Mae or anyone else in the neighborhood who might have had a tongue for gossip. And in exchange, Willa Mae got to hold on to her dignity. Sometimes, she looked at that kind of old-school discretion as a blessing, a gift. Most times, it felt like a ticking bomb.

Willa Mae has almost made it past the dresser, dragging the nightstand closer still to the closet, when she yanks once more and hears something tear. Her right breast nearly flaps out of her nightgown. She looks down and sees that one of the front peg legs has come down on the gown, pinning the gauzy material underneath it and making it tear at the shoulder. This is what happens when she’s not careful. She’s lucky she didn’t catch skin.

What to do, what to do? She’s left the cordless phone in the living room—but even if it was within reach who could she call, to catch her indecent like this? She tugs at the material, trying to free it, but it only rips more. “Well,” she sighs, looking up at the framed picture of Senior the children have left for her on top of the dresser. It’s a candid someone snapped at the retirement party the electric company threw in his honor. Early 2000s. He is hovering over his cake and glancing casual at the camera, as if someone with whom he is close, with whom he is playful, has just called his name. His mouth curls up with mischief. “Daddy’s so handsome in this one,” Carole had cooed after Senior’s funeral, dusting the photo lovingly. “Look at him flirting . . . He must be looking at you, Mama.” And again, Willa Mae had held her tongue. She’d unpinned her black fascinator, the fine netting of which had covered her face like a cloud throughout the ceremony, and remembered that of all the women who’d been at that retirement party—all those women who she could not say were as clandestinely decent as Doris Cleghorne—Willa Mae most certainly had not been the one to snap that picture.

How Senior might smirk to see her now, though, stuck as she is on the floor. “You doin’ too much,” he liked to tease once he was retired and Willa Mae would attempt anything new, like the gluten-free low-sugar cookie recipe, or the modified version of the sunrise salutation. She was only trying to show her husband that life didn’t have to end when the children left home or the job pushed you out or your friends up and died on you, one by one. But he mostly ignored her prattling about details.

Willa Mae still can’t clear the gown from underneath the nightstand, but she’s come too far to stop now. She yanks and yanks, pulling against the tear. Encouraging it. At first she only feels resistance, then the rip races down like a run in pantyhose. The entire left side of the nightgown falls away, and the right, struggling for one string of a second to hang on, slips off her shoulder. Gingerly, naked except for her underwear, Willa Mae wriggles backward, out of the fabric. She finds her footing and stands up, free.

It’s a risk to do this—oh, Lord Jesus, her back!—but there’s only a little farther to go now. She bends down from the waist to tug hard a few times at the legs, panting with the effort, the discarded nightgown getting tangled up worse, and when the front edge of the nightstand reaches the open closet door she walks around to the other side of it. With her hip, she pushes the wood until it is partially inside the closet, pushes against the few hanging clothes she’s been able to reach by herself. Pushes until there is just enough tabletop exposed for her feet. Her heart is exploding and the step up is high, but she can see the box now, the QVC logo hovering above. A flash of outrage grips her again: My house, she seethes, and I can get what I want.

Willa Mae grabs the jamb with her left hand. Inhales, and on the exhale raises her left leg, planting her foot on top of the nightstand. Inhales, and on the exhale pushes off with her right foot—up, old girl, up! She ignores the twinge in her hip as the joint rotates, and nearly hits her head on top of the jamb. But then there it is. A wobbly, most unusual sight: that high shelf, hitting right at eye level. That shoebox ready and waiting.

“Hah!” she cheers. “Hah!”

The next morning, before visiting Doris, Willa Mae runs a bath. When she finishes washing, she wraps herself in a towel, pulls the clodhoppers from under the bed, and drops them into the soap-scummy water, like the boats that they are. They bob for a minute—“WATERPROOF!” it says across the tongues, in the same horrible hue as the lightning bolts—but Willa Mae fishes for each and, crouched on the bath rug, she pushes them down until a balance tips and they are sinking of their own accord, waterlogged, ruined. She drains the tub and the clodhoppers glug toward the drain, done. She can’t wait to tell Doris.

She puts on fresh underwear, the stockings, the floral blouse and the cardigan and the slacks that look like blue jeans but aren’t. She puts on Diahann. The jewelry, she decides, is too much for today. She sits on the edge of her bed, the morning light filtering in through the blinds, and opens the rescued QVC shoebox. The last surviving pair. Inside, to her surprise and delight: slingback kitten heels, with silver buckles across their pointy toes. She pulls them out one by one from the tissue paper. The leather is as smooth as the seats of Senior’s old Cadillac, which she never did learn how to drive, and they are the butter-luscious color of French vanilla ice cream. Happy birthday to me, she sings, belatedly. When she twists the shoes this way and that, coaxing out the wad of paper balled inside each of the toe boxes, the buckles gleam even through protective cling plastic. She pinches the plastic between her fingernails until it peels away, and flicks it into the detritus of the shoebox. She slips the left one on and then the right. Already she can tell they don’t fit quite right, but she stands up anyway. Already she can feel the blisters forming, her feet struggling to spread to their full width and length.

Best to get a move on, then. Willa Mae checks the stove and the back-door lock, finds her pocketbook, and opens her front door. Feels the skin above her heels chafe as she shuffles across the porch, down the steps, and across McMillan. Outside the yellow house, the Cleghornes have piled up their cars something awful. She squeezes between them.

A shapely, sweet-faced girl answers Willa Mae’s knock and welcomes her inside. The girl has a New York accent and hair down her back and a sparkling jewel stuck through one nostril. She’s Maurice’s friend, she explains. “Oh, you the one Doris likes!” Willa Mae exclaims, and the girl blushes.

The kitten heels make a tapping noise on the linoleum in the kitchen, where a gang of Cleghornes, even Maurice, is cooking up a feast for later. Giant pots that can make many helpings, for portioning into Tupperware and freezer bags. They chop and stir and wash and dry, maneuvering around each other. The space is tight but the feeling is warm. Doris, she sees, is blessed. Even if the collards do smell a bit off.

Maurice, after popping a muffin tin in the oven, takes Willa Mae by the arm and helps her up the stairs. “You charmer,” Willa Mae jokes, and Maurice gives her a tired smile. His mother, he explains outside the bedroom door, has a long road to recovery. The hospital had wanted to keep her one more day, but Doris, despite having lost muscle control on the left side of her face, was able to communicate that she wanted to come home. And so her sons and their women will take turns looking after her.

Doris is in pajamas, propped up with pillows, the lower half of her body under the covers. It is hard to believe she was ever tall and broad, that until recently she was buzzing about in her tracksuits and tennis shoes, looking every bit the active senior. But it’s clear that she recognizes Willa Mae, the way she moves her neck slightly, her eyes going up and down. Maurice pulls up a chair next to the bed for Willa Mae to sit, then leaves them alone.

“Well,” Willa Mae sighs, and bends down to kiss Doris’s cheek. The side that droops. She looks around the bedroom. Endless bottles of medication sit on a TV tray beside the bed, but there are also silk flowers everywhere—violets and roses, orchids. Photos of Doris’s smiling sons hang in random patterns on the tangerine-colored walls. Her tracksuits line up in the closet, a rainbow of colors. Not exactly Willa Mae’s style. But nice, in their own way.

With her good arm, Doris gestures to the floor, toward Willa Mae’s gleaming new slingbacks. She burbles, stutters, attempts to form the word. “B-b-b-b . . . B-ewww . . .”

“Yes,” Willa Mae says, “beautiful, Doris. Your home is just beautiful.”