The Second Sight of Henry Dumas

Envisioning Black (Im)possibility in the U.S. South

By Carter Mathes

Black in the Midst of the Red, White, and Blue, 2017, by Lonnie Holley. Courtesy the artist and Paulson Fontaine Press

I.

Well over a century ago, W. E. B. Du Bois famously characterized the complexity of being Black in the U.S. as the condition of double consciousness. This “two-ness” can be felt with a direct and physical immediacy in how one is confronted with white supremacy structurally or intimately. It can be understood through the psychic weight, the accretion of knowledge gained through experience and study that one builds and carries through careful and close analysis. Du Bois is clear that the double consciousness of Blackness is not simply deficit, obstacle, and pain, but a condition that also reflects the possibility of second sight. To have second sight is to be a visionary, a seer; while we all can’t claim that status simply by virtue of being Black, it is necessary to acknowledge not only how African American artists and wordsmiths have translated aspects of that second sight onto the page, the canvas, the score, or elsewhere, but also that these Black aesthetic inclinations permeate African American life in ways that are too often ignored at our own peril.

My grandfather possessed deep sight shaped by his roots and memories anchored in our familial history of Virginia enslavement and its aftermath. I learned from taking in his prophetic stories and visions how the space of time, memory, and geography outlining the relationship between African American–ness and the U.S. South is complicated, multi-directional. The South is simultaneously a collection of different but interconnected spaces, and an intriguingly ephemeral trace, a connective thread, a resonant echo of Black being.

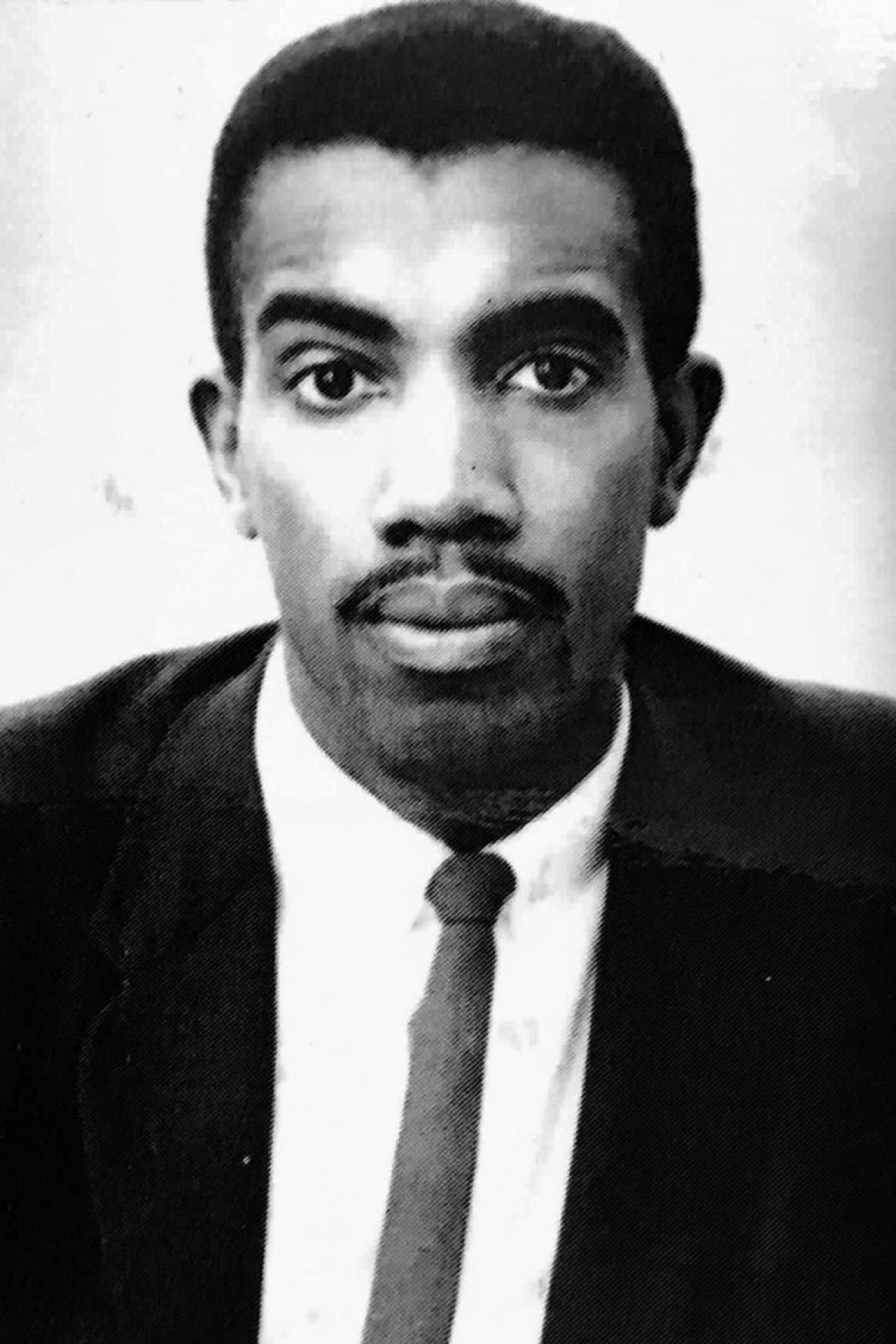

Henry Dumas was an all too often overlooked and understudied African American writer of the 1960s who died at the hands of a transit policeman in New York City at age 33 in 1968. He produced a vast and dazzling body of work that encompassed the multiplicity of experiences and expressions Du Bois described. Born in Sweet Home, Arkansas, in 1934, Dumas drew upon his rural Southern childhood, his urban adopted home, and his mystic imagination to both expand the scope of Black expression and ground it in a life I recognized in my grandfather’s stories.

I first encountered Dumas’s fictional omniverse—as Eugene Redmond, the late author’s editor and literary executor—has so appropriately deemed it, as a graduate student in the late 1990s and early 2000s while writing about the Black Arts Movement of the 1960s and 1970s. At the time, there had been very little attention paid to Dumas since a 1988 special issue of Black American Literature Forum. My mentor, Barbara Christian, had gotten to know the author’s contributions quite well from her close relationship to the movement as it took shape in New York City. On more than one occasion, she recalled the multi-sensory experience of Sun Ra and his Myth Science Arkestra leading a procession of artists through the streets of Harlem, a scene of revolutionary hope and Black futuristic sound. In Dr. Christian’s view, Sun Ra was part of a movement within the movement that included Henry Dumas, Jayne Cortez, and other more experimental and surrealistically inclined Black artists. Pursuing this trail on the heels of her instructive reflections brought me deep into Henry Dumas’s work, but so did my grandfather’s prophetic inclinations, his consistent awareness of mystery, and his strong belief in the supernatural and the not quite fully known.

“Will the Circle Be Unbroken?” is perhaps one of Dumas’s best-known stories. First published in 1966, the tale focuses on a legendary soprano saxophonist, Probe, who has mysteriously returned from exile with a fabled “afro-horn” able to project a “new sound” for an all-Black audience at the Sound Barrier Club. A mystical confrontation arises when three white hipsters, Jan, Ron, and Tasha, insist on gaining entrance to the venue so that they can experience firsthand the latest developments in the new Black music. The story reveals the hipsters to each be grounded in degrees of crises they cannot clearly recognize as they attempt to “break the circle of the Sound Club” and unlock the mystery of Probe’s innovations. Dumas critically inverts the insiderism that Jan, Ron, and Tasha each feel through musical, journalistic, and romantic connections to the music by instead showing the vast gulf separating each of them from what they assumed was theirs to know, as the force of the music hits them and leaves them in suspended states of existence in which each “mind went black.” While the story offers a resolution of the conflict between invasive whiteness and communal Blackness, the lasting resonance may lie in Dumas’s understanding that the sonic forms of things unknown, the music of elsewhere that Probe creates, can bridge the ancient and mystical formations of Blackness with the precise political immediacy of Black collectivity. “Will the Circle Be Unbroken?,” like many of Dumas’s creative forays into Black life and Black thought, asks us to sit with the magic of Blackness that rejects the authority of Western empirical thought, the magic that instead reveals the spiritual, ghostly, cosmological outer reaches of Black experience, memory, and possibility.

There is much weaving of words, characters, themes, images, sounds, motifs, and vibrations among the various works composing his fictional and poetic looms, as the spiritual power of Probe’s horn as a force of judgement and renewal echoes and reverberates through Dumas’s poetic request to “Listen to the Sound of My Horn.”

The mystical strains of Black possibility run throughout Dumas’s poetry, including the volume Poetry for My People, later reprinted by Toni Morrison as Play Ebony, Play Ivory (plus one “selected”), two short-story collections (plus one “new and selected” and one “collected”), and one novel (edited and published posthumously). Dumas’s interwoven Northern and Southern landscapes of Black life in many ways reflect his own geographic movements, rhythms, and sensibilities. By the time he was ten, however, in large part because of his precocious nature, Dumas’s family made the decision that Henry should move north to live with his great-aunt in New York City so that he could take advantage of greater educational opportunities. Moving between Sweet Home and New York City initially, Dumas’s orbit would ultimately expand beyond the north-south, rural-urban flows within the U.S. into the Arabian Peninsula, where he served in the U.S. Air Force during the mid-1950s. Dumas’s capacious literary range can be felt and heard through the fusion of Arabic chants, blues musicality, West African points of cultural reference, African American urban and Southern folk vernacular, and the Afrofuturistic dimensions of experimental Black music that appear in his writing.

The sound Dumas is imagining and rendering on the page in the poem “Listen to the Sound of My Horn,” not unlike his representation of Probe’s afro-horn in “Will the Circle Be Unbroken?,” projects and reflects visions of Black life, from the marking of “the time to rise for the fields” to the salvific “rhythm as the congregation kneels.” The living, breathing qualities of Dumas’s rendering of Black sound exist in the “note of air” as well as the “voice of your despair” and is pushed further through Dumas’s concluding lines asking the reader to hear the history and memory of “years long past” while also acknowledging the immediacy of the sound in all of its newness and future possibility of arrival, punctuated by his final rejoinder “Great music and I . . . have come at last!” The flowing sound keeps running like a Dumas word river as wide, deep, and winding as the Mississippi itself. His poem “Mississippi Song” opens up further connective possibilities between his works. Channeling the perspective of the river as both a thinking and embodied being, the poem offers prophetic guidance as to how a Black collective might “put the bones together,” relish in the “sun splatter” of the natural world, and announce the arrival of self-determination: “our name . . . our voice.”

Dumas’s sense of belief and righteousness offers a generative interplay between ideas of Black political resistance and visionary Black religious doctrine and practice. In my case, arriving at Dumas’s work through an academic lens has created a dilation of that lens beyond the academic that has allowed me to reflect on the ways place, exile, spirituality, and roots inform and emerge from the power and craft of narration. When I speak of narration, I don’t simply mean storytelling, but rather an embodied telling and understanding of what the telling can and can’t reveal.

II.

When I was growing up, I spent parts of summers with my maternal grandparents in Dorothy, a small, small town set back in the rural pine barrens of southern New Jersey. They had moved there from north Jersey by the early 1970s, around the time of my birth in D.C. The land was heavily wooded, sandy-soiled, freight-train-tracked, isolated-country-store-dotted, and flat in a way that reminded you that the salt air of the coast was not far off. It was in the context of experiencing that land as a central part of my coming of age, in a part of New Jersey that feels ecologically linked to the southeast more than the northeast, that my grandfather, Charles Carter, shared with me different hints of his past and the pasts before his. A storyteller, he would pass much time with me talking while working outside in the large garden where he experimented with new crops and new ideas (building a greenhouse, becoming a beekeeper, constructing a root cellar); or riding with me along the rural isolated roads on an old bike that wasn’t built for tandem but was big and sturdy enough to accommodate us both; or in the narrow rectangular curiosity- and book-filled room he had constructed off the kitchen. He spun yarns from his past and the pasts before his and wrapped me in his memories, his visions, his sense of history.

My grandfather was a quiet and small but powerful and very big-handed man. Slight but serious and nothing if not mysterious. He told me he had come back from the dead as a young man when he was working for a wealthy white lawyer in rural Pennsylvania. His parents had migrated in the late 1800s from Richmond, Virginia, to Steelton, a small rust belt borough bordering the state capital, Harrisburg, on the banks of the Susquehanna River—part of the Black southern migration encouraged by Pennsylvania Steel. The temptation and hold of the bottle on my great-grandfather, Lewis, pushed his wife, Martha, to relocate the family to the countryside away from the taverns of Black Steelton once she was able to secure a live-in job as a domestic on the Wilson family’s Mifflinville farm.

When he was a young man, an elder teen really, my grandfather became a butler and handyman in charge of various operations on the property. On some occasions he was tasked with handling highly flammable and combustible chemicals that were stored in a shed. One day while walking out of the structure, one of his white co-workers casually disposed of a still burning match while lighting a cigarette nearby. As Grandpa Charles tells it, he saw the match fly in slow motion toward the open door of the shed he was just crossing the threshold of, and was both mouthing “NO!” and trying to launch himself beyond the explosion engulfing him. He had third-degree burns across his lower body and a declining pulse. What he remembered, what he recalled to me, was waking up from the blast, but not really being awake, in the hospital. Even though he knew where he was and could see family members and doctors, no one would respond to what he thought was his voice when he called out. “They read me my last rites,” he said, and I wasn’t sure if he was also telling me this from the perspective of that inside person who is watching but can’t be seen or heard, or from what others told him later. He viewed the explosion in light of the fact that a scholarship for higher education, which he was awarded based on his high marks in science and math, was revoked due to his race. He’d had the rug pulled out from under him, and layered on top of that, almost lost his life. Piecing this together, I can tell now that my grandfather’s encounter with the other side pushed his awareness of other dimensions of being and knowing.

I rarely spent a day with him that didn’t include moments when we would be sitting together, and he would ask me, “Did you see that?” He told me that he could see angels, spirits, and presences that were moving between dimensions, and so could we all if we paid attention. The corners of our eyes reveal more than we care to know. If we let our vision linger through the corners and appreciate the stillness of long moments, we might sense the folds between dimensions and catch the spirits moving between them.

Now on the other side of years of life experience and knowledge gained since then, with the awareness that memory is anything but linear, another story my grandfather told me feels infused with his sense of justice, reparation, and attunement to the other planes of existence and possibility. I’m not sure where and when he first shared this with me, but when it enters my mind, I remember the cement front porch and the loose gray stone driveway leading up to the house.

An ancestor had passed down a story of bearing witness while working as part of a crew of enslaved Africans clearing marshland in the Northern Neck of Virginia. The group included a young woman trying to work with a baby strapped to her, repeatedly getting the crack of the whip to speed her work up. The slavedriver grew impatient with her pace and suddenly went to her, grabbed the baby and beat the child to death against a log while the woman, restrained by other enslaved workers, watched and wailed with, my grandfather said, “terror and damnation in her eyes.” She could continue to work or die in the immediate wake of this everlasting horror, and she chose to continue numbly. An enslaved man, a brother, sharply, quickly, whispered to her, “He get his.” The next day, the thick, wild terrain farther back into the marshland slowed down the crew. Another group of men, up ahead, called out to the slavedriver, saying a fearful word or phrase about snakes. When the driver rode over toward the group to tell them something like “clear or die,” they pulled him off his horse and out of sight into the bush. With his mouth covered, they machete chopped his body into tiny bits with a quickness. Bits of what used to be a man, but was never really human, were dispersed into the marsh. The group sent his horse off riderless; they knew the horse would likely come back later to the camp, empty, proving their story that the slavedriver had gone looking for something deep back up in the bush and just never came back . . .

The way my grandfather told this story, the convergence of the narrative substance and his sound—the way he projected the story through a steady, quiet, almost flat intonation that he’d suddenly and unexpectedly punctuate with his rendering of the eruptive sounds of a cry, struggle, machete chops, the atmosphere and depth of perspective, as if he were there on the scene—imprinted me with a sense of racial justice and reparation at an early age before I knew what I was hearing fully meant. Or maybe this is the time when we actually know more of what truths can and should mean. That is, prior to being channeled into the many different societal folds that erode and steer us away from the magical possibilities of being.

III.

The idea of truth is always fungible, and the various intersections of Blackness and the felt truths of being within contexts of white supremacy simultaneously enhance and erode that fungibility. Put another way, what it means to be Black is all too often at once multi-dimensional from within and singular from without. Dumas’s creative visions speak to the multiplicity of Black insight. Not unlike his sonic collaborator and mentor Sun Ra, who also looked toward Black futures extending beyond the parameters of the here and now, by anachronistically going to the ancient past of Egypt, Henry Dumas wrote a significant portion of his oeuvre as a fictional exploration of returning to the U.S. South as a source of Black life—as both history and future possibility. “The natural world was full of negotiations, contradictions, beauty, and brutality,” as his biographer Jeffrey Leak puts it. His widow, Loretta Dumas, notes that Henry excelled in his new urban fast-paced surroundings, while also regularly returning for visits to Arkansas, maintaining what she refers to as his “country allegiance.” When visiting her family in Westwood, New Jersey, in the 1950s, at the time somewhat of a rural New Jersey hamlet, Henry was taken with the countryside setting and told her father, “You can take the boy out of the country, but not the country out of the boy.”

Dumas’s relationship to the South is infused with wonder, mystery, possibility, and loss. His Southernness as a Black man and as a creative artist is filtered through his memory and relationship to the rural landscapes surrounding Sweet Home, and was augmented through the sonic and philosophical explorations of Sun Ra’s sound and philosophy. Dumas’s relationship with Sun Ra blossomed during what would be an ascendingly productive part of his life and artistic career that was cut short at the hands of a New York City transit policeman on the evening of May 23, 1968, under still not entirely clear circumstances. Reflections on the shooting are derived from conversations between several of Dumas’s friends and the police who were at the city morgue the next day when Dumas’s friends came to identify his body. Dumas’s friends were told that the incident was seemingly precipitated due to an altercation between a knife-wielding Dumas and a group of individuals on the 125th St. and Lenox Avenue subway station platform. In attempting to intervene, the transit policeman apparently felt threatened and took the life of Dumas as a result. The officer recounts firing his weapon in an official statement, which, according to Dumas’s biographer, Jeffrey Leak, is the only account that remains, as the records were seemingly destroyed when the New York City Transit Police became a bureau within the NYPD in the mid-1990s.

Dumas had returned to New York to be the best man in his friend, Bill Seiboth's wedding after he’d relocated to the Midwest in early 1967 to work at Hiram College in Ohio with the Upward Bound program and later as an editor for the Hiram Poetry Review. Dumas published three poems—“Ngoma,” “My Little Boy,” and “Montage”—in the inaugural issue, while the third issue contains a document penned by Dumas and entitled, “AN INTERVIEW WITH SUN RA: Excerpts from a Longer Article (in Progress).” Parts of the interview can be heard on The Ark and the Ankh: Sun Ra/Henry Dumas in Conversation 1966, a 2004 IKEF record label release of twenty-four minutes of dialogue between Dumas and Sun Ra recorded at the storied Lower East Side nightclub Slug’s Saloon.

The interview excerpts reflect the strong connection and affinity Dumas felt for Sun Ra’s ideas of Black sonic metaphysics and cosmology. He frames the excerpts with Sun Ra’s definition of music as “a living soul force . . . a plane of wisdom . . . the universal language,” and describes Sun Ra as a “musician with a great message of spiritual rehabilitation and wisdom . . . tirelessly working among Afro-Americans.” In some ways, the connection Dumas expresses with Sun Ra’s ideas reflects what he may have recognized as the proximity of their positions on the frontiers or far horizons of Black possibility and futurity. Dumas also seems well aware of the fine line between the visionary and prophetic qualities of such a positionality poised on the promise of radical new discovery, and the social and artistic marginalization one often experiences in claiming that ground in the face of “infantile critics” lacking any tolerance for what seems to push notions of rationality and artistic value beyond the boundaries of mainstream acceptability and comprehension. Dumas’s words do not blink when Sun Ra explains himself to be “on another plane of existence,” and describes his Astro-Infinity music as “beyond freedom . . . the design of another world.”

The last excerpt that Dumas includes may be the most telling. Sun Ra makes explicit connection between the sounds he is creating musically and natural forces that can “give some order and harmony to this planet.” According to Sun Ra the natural world is an enabling force that “gets under you and drives you to do what you thought you couldn’t.”

The connection between these two Southern Black visionary artists, seers in the deepest senses of the word, revolves around the possibilities for otherworldly, at times interstellar expansion and possibility that can emerge from the landscapes and natural elements marking the everyday. The fantastic, for Sun Ra, was intertwined with the quotidian. Accessing other planes, other dimensions of being was not about literal space travel. Rather, Sun Ra felt that reorientations and adjustments had to be made within Black consciousness so that Black people might foster and grow with “new mind-cepts” that break destructive patterns of “worshipping death instead of trying to understand the ways of his Creator.”

Dumas forged ahead with expansions of Sun Ra’s ideas not only through his creative literary work, but also in penning the liner notes for the 1967 release of Sun Ra and His Myth Science Arkestra’s album Cosmic Tones for Mental Therapy. Several tracks from this album, originally recorded in 1963, can be heard in the background of the recorded conversation at Slug’s Saloon. Dumas’s brief liner notes echo and resonate with the oblique visionary perspective of Sun Ra in situating the cosmic within the immediacy of the psychic and bodily:

WHEN YOU CAN MOVE IN A DIMENSION FASTER THAN LIGHT YOU SOLVE THE RIDDLE OF TIME AND YOUR MIND’S COSMOSIS COMPLETES THE EQUATION: LIFE EQUALS DEATH, FOR IN THE EXPANDING UNIVERSE THE INFINITE DESTROYS THE ILLUSION OF LIMITATIONS WHICH TRAP MAN TO THE PLANET EARTH.

Dumas’s affinity with the teachings of Sun Ra discloses how deeply he understood the sense of exile and displacement in the space between Sun Ra’s visions of prophetic and apocalyptic Blackness and what Sun Ra saw as most Black people’s inability to realize the truths within his words, his cosmic equations, his sounds that reached into other dimensions.

IV.

For Dumas, in addition to his recognition of the alienation that Sun Ra knew, his own sense of exile was amplified by the distance he felt from Sweet Home. Exile, the concept so central to my bridging of Dumas, my grandfather, and myself, is not simply to be felt in its negative connotations, but also as a kind of tension between displacement and possibility, because the absence that it brings creates the conditions for continued searching and seeing. To figure out why here is not present and what here actually is demands a proximity to the elsewhere.

Dumas’s short story “Echo Tree” offers a rich distillation of this weighty sense of belonging and longing through his portrayal of two young African American men walking through a windy Southern countryside in search of a mythical and powerful tree to commune with the spirit of Leo, the brother of one of the young men, and good friend of the other, who has recently passed away. We learn that Leo’s brother has returned to the countryside after living for a time in New York City. The city, Leo’s friend says, echoing the knowledge he recalls from the brothers’ grandfather, “messes you up.” Leo’s friend is a conjurer, a disciple of Leo’s brother, who taught him “how to use callin words for spirit-talk,” and has also warned him of the dangers of even inadvertently cursing the tree, a warning he reiterates to Leo’s brother: “If you curse the echo tree, you turns into a bino.” Dumas leans into the tension around Leo’s brother’s remove from the natural world and the spiritual dimensions of his homeplace, perhaps as a way of signaling the tensions of Southern geographic and spiritual exile he felt himself. Turning “bino” is to pass into an ignorant, perilous state of disbelief in which “the spirit leave out your body, you pukes, you rolls on the ground, you turns stone white all over, your eyes, your hair. Even your blood, ’n it come out your skin, white like water.” To be bino is to be internally exiled from oneself by choosing to ignore the power of the spirits surrounding our everyday. “You just gotta know how to talk to the spirits,” Leo’s friend states. “They teach you everything.” Minnie Rose Hayes, Dumas's cousin, and current Director of the Henry L. Dumas Foundation, has explained that the short story seems to reference a natural abundant space of fruit and nut trees only blocks from Sweet Home that the community knew as Echo Valley, a place where one “could make sounds, call out names and it actually would echo over and over again.”

Dumas’s stories set within Southern rural landscapes are distinguished by this seamless blending of the quotidian and the fantastic. In the titular story of his first collection of fiction, “Ark of Bones,” he brings us into the Southern rural world of two young Black men, Headeye and Fish-hound, as they walk through the land surrounding the Mississippi river. Headeye surreptitiously guides Fish-hound, mojo bone in hand, to a point in the river where they encounter “the damnest thing I ever seed . . . the biggest boat in the whole world . . . what I took for clouds was sails.” Dumas’s representation of this ark, what Headeye calls a “soul boat,” almost hovering over the water and beckoning Headeye and Fish-hound, references Biblical ideas of Noah’s ark and Ezekiel’s prophetic vision of the Valley of Dry Bones, as well as Sun Ra’s reconfiguration of ark symbology within his formations of sound and spectacle. Once the two young men enter the mythic ark, they witness an ancient, otherworldly Black crew harvesting bones from the river’s bottom and storing them in the “great bonehouse” of the ark’s hold. Dumas narrates these moments of the young men’s encounter with this eruption of the mythic in the Southern countryside with a prophetic focus on Headeye, who has been chosen and anointed a guardian of his people by a priest on the ark. After the encounter with the ark, Headeye ventures off to further his mystical duties, telling Fish-hound, “I’m goin, but someday I be back. You is my witness.”

Within the recurring, slightly interwoven elements of Dumas’s Southern landscapes, the prophetic formation of Headeye’s character might be seen as reemerging in the character Fon, who shares his name with the title of another pivotal story in the original Ark of Bones collection. “Fon,” a reference to the West African people of the Dahomey kingdom (present-day Benin), is a shortened name for Alfonso, a young Black man who has been apprehended by a group of white men who plan to lynch him. What seems initially to be an all too recognizable tale of Jim Crow–era violence instead becomes a depiction of Black resistance in which white supremacy is first psychically displaced through Fon’s mystical power, seemingly derived from ancient African connections, and then brutally vanquished by mysterious arrows that pierce the necks of the white men as they prepare to lynch Fon. Dumas concludes the story with Fon’s reflective voice: “That was mighty close. But it is better this way. To have looked at them would have been too much. Four centuries of black eyes burning into four weak white men . . . would’ve set the whole earth on fire. Not yet, he thinks, not yet . . .”

The brick supposedly thrown by Fon is presaged by a moment in Dumas’s unfinished novel Jonoah and the Green Stone, when a brick is thrown by Jubal, the titular character Jonoah’s adopted brother possibly named in reference to the originary musician of the Old Testament, a central character who resonates with the visionary capacities of both Headeye and Fon. Once again it is the Mississippi River at the center, and in this case a 1937 flood that has created chaos and displacement for Jon, a six-year-old boy adrift and alone, and a family who rescues him on its impromptu raft. The family and Jon, who Papa Lem, the grandfather on the raft, dubs Jonoah, combining his name with a reference to Noah which befits the ark-like situation they find themselves in, are forced to take a racist white man, Whitlock, on board. Jonoah wanders in and out of the South across decades as he grows into adulthood, continually in search of answers to unanswerable existential questions that revolve around his layered exilic status of displacement (from his original and adoptive families, from his past generally, and therefore from a land and place to truly call his own) and his relationship to the Civil Rights Movement as he experiences elements of it in both southern and northern locales. The unfinished novel often feels like a dreamscape, Dumas’s prose moving in and out of hidden metaphors and glimmers of allegory, as well as the fractured meditations of Jonoah.

“To dream is to know,” I remember my grandfather telling me on more than one occasion. I realize that this phrase must have meant many things to him, not all of which I’ll ever know. But I do feel the vibration of these words of his in reminding me always that when your existence is poised on various kinds of precarity, the substance of visions is as real as the earth, the air, the water. It is not easy to situate oneself, if even for brief moments, on the other side of time, the other side of somewhere, to gloss the wisdom of Sun Ra. For Henry Dumas, my grandfather, Barbara Christian, and Sun Ra, the convergences between place, memory, and the ethereal held great possibilities beyond but also always informing our most pressing sense of here and now. This writing is an elegy to the convergent legacies of ancestors known in different ways. I write in this present political moment not simply to honor them, but in affiliation with this orientation toward roots, struggle, and the potential for new kinds of Black futurity, as Dumas reminds us, “to illuminate the greater part / of ourselves / to add structure to the music we hear / to add dimension to sound.”