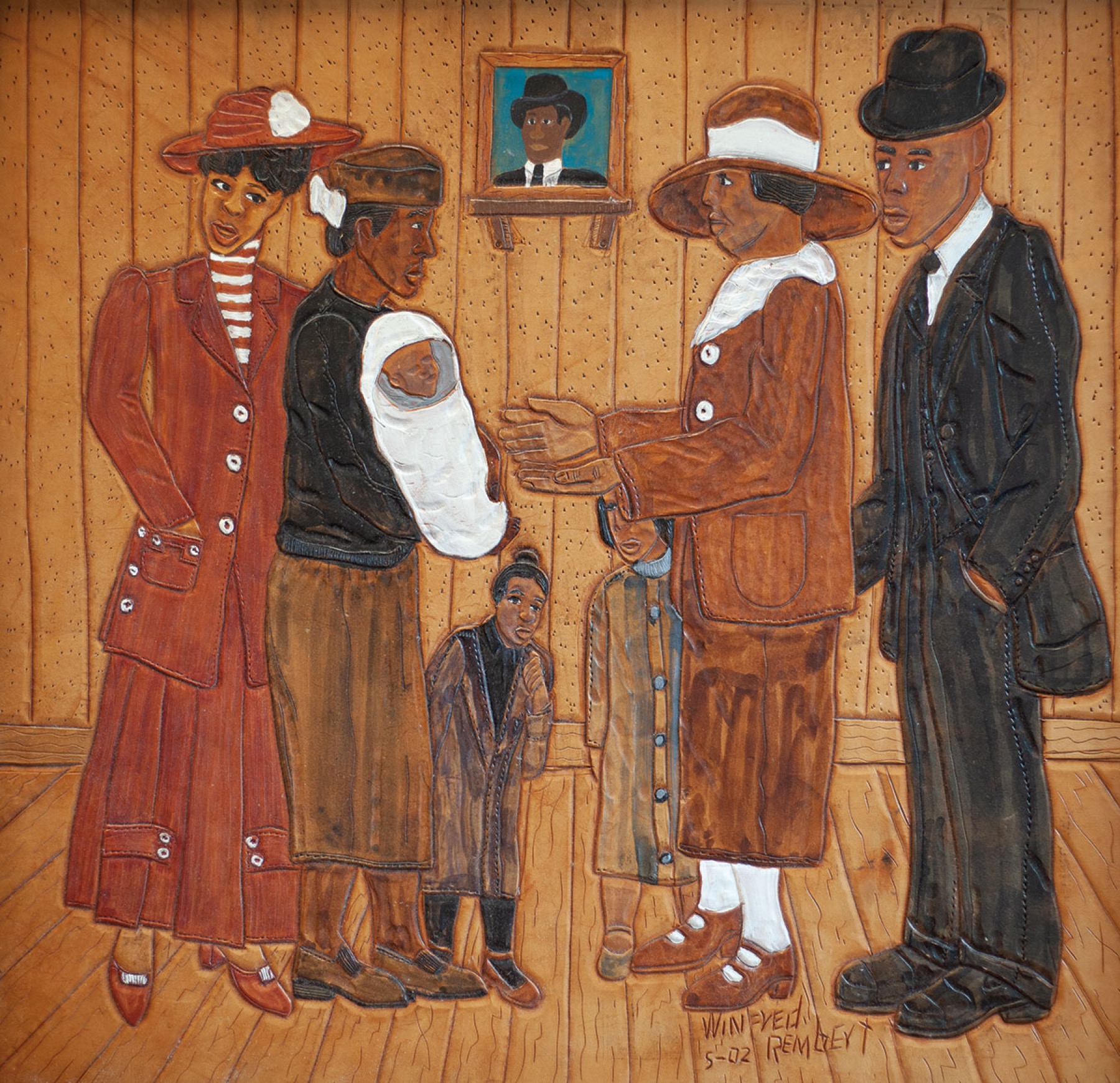

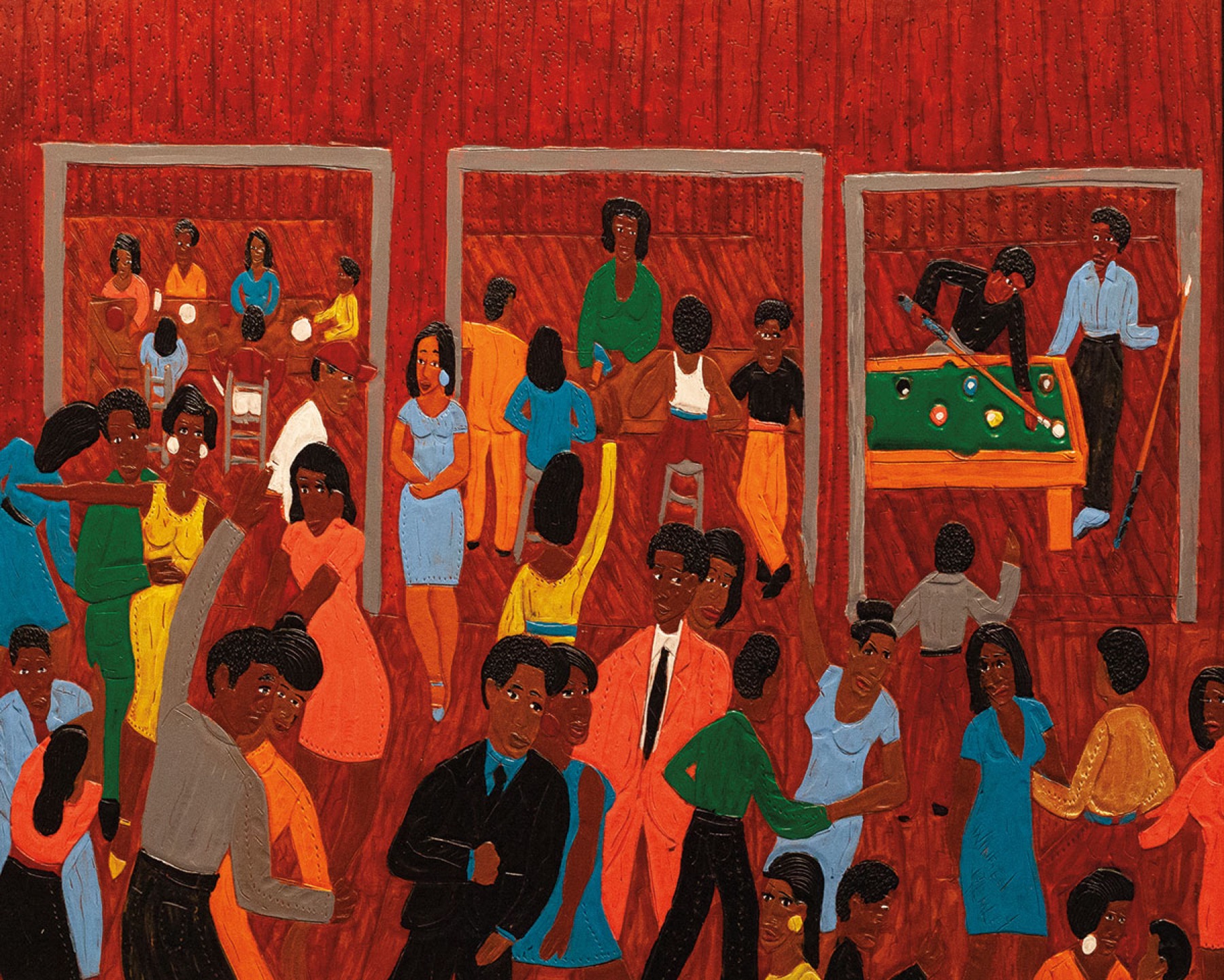

"Bubba Dukes and Feet's Pool Hall," 2002. Dye on carved and tooled leather. All works courtesy Fort Gansevoort, New York. ©2022 Winfred Rembert / ARS NY

Coda for Winfred Rembert

Two recent exhibitions feature scenes depicted in the artist's memoir, Chasing Me to My Grave

By Rebecca Bengal

Cotton, the earliest memory: as seen by a boy child riding upon the sack through the endless rows, a horizon like snow. “Just as far as I could see, all the way around, there was this white sheet of cotton,” the artist Winfred Rembert would write in Chasing Me to My Grave, his 2021 memoir of surviving an attempted lynching by a mob of white men as a teenager and of the astonishing life that followed. “I remember the cotton over the top of Mama.” Mama—not biologically, but the great-aunt who raised him as her own son, whose cures for his childhood aches were the tinctures she made of sugar and turpentine. Because in Jim Crow Georgia, you couldn’t depend on doctors to save you.

The field, the first thing he fled in rural Cuthbert: “When you get out there picking in it, though, you change your mind about how beautiful it is.” A runaway from age thirteen, in the late 1950s and early 1960s, he rested his head on gravestones, in the back rooms of downtown pool halls on Hamilton Avenue. It was the first time he’d encountered a world of juke joints and dancing and barbershops and other businesses owned by Black people—“I walked from one world into another when I came out of the cotton field and discovered all those smiling faces, all those people doing well and not picking no cotton.”

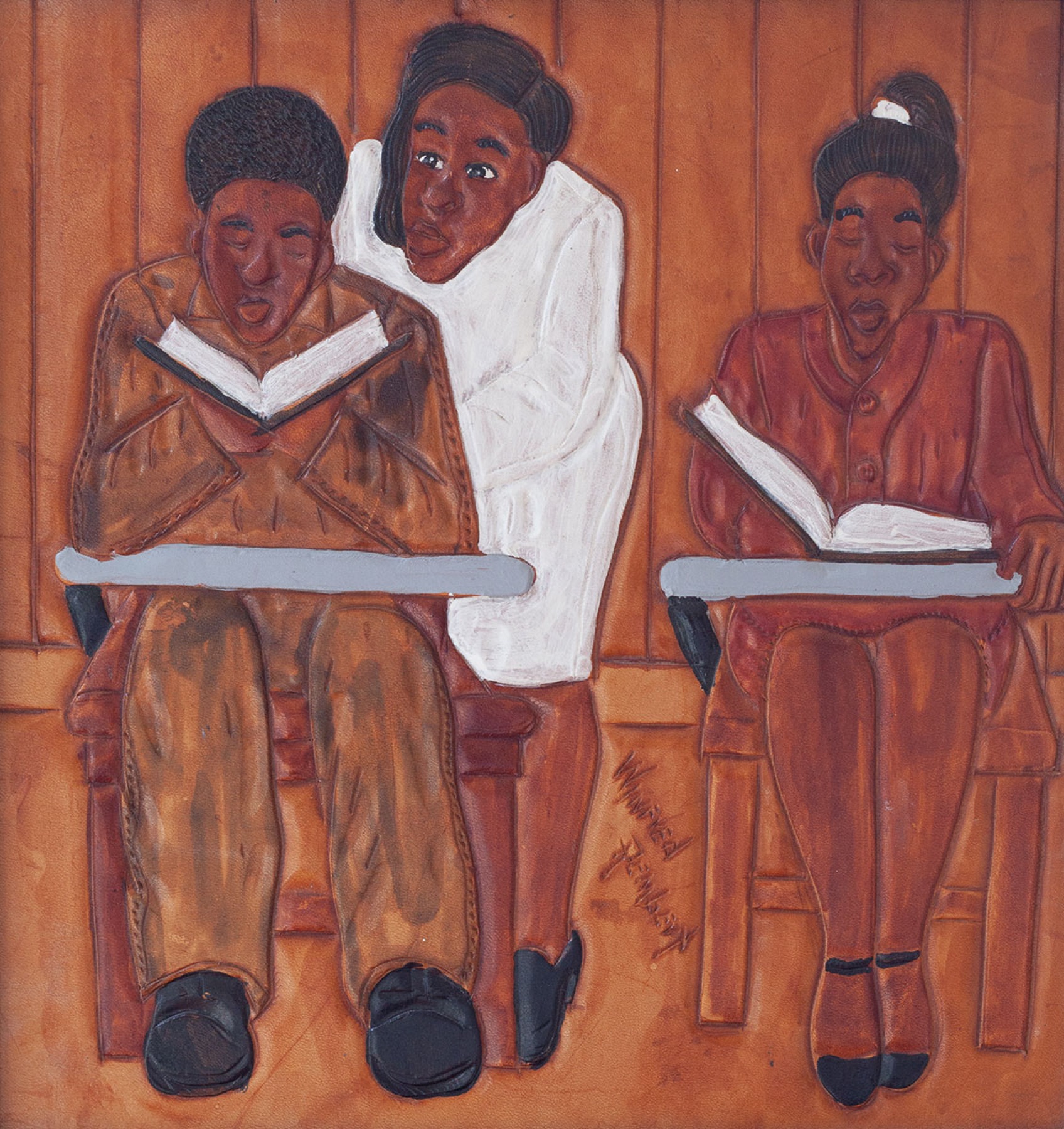

Sometime in the late ’60s, early ’70s, when Rembert was doing hard labor in prison, a fellow incarcerated man taught him the craft of making designs on leather. Rembert’s billfolds and purses, which he illustrated with drawings of musicians and dancers, got so popular that he could charge up to twenty-five dollars for them. “I also wanted to make beautiful things I could bring home,” he wrote. But it wasn’t until near the end of the century when Rembert—at his wife Patsy’s urging—began to turn hides into a canvas for his own life story. By this time, he was a father of eight. First on Stop & Shop grocery bags, and finally leather, he began to depict the scenes from his early life that, many years later and hundreds of miles north of Georgia, nonetheless still stalked his sleep and terrorized his nights. He recalls in the book how Patsy reminded him: “Winfred, you got to remember: [...] Nobody tells their life story on leather. Nobody.” Nobody in the art world anyway. Unintentionally, Rembert’s practice was in keeping with numerous Native American peoples of the Great Plains who for centuries painted tribal histories—tales of war, winter counts—on animal hides.

Narratively, Rembert’s leather artworks are kindred to Jacob Lawrence’s Migration Series: sixty paintings chronicling stories of the post–World War I movement of Black Americans from the rural South to points West, to the urban North. Seen in 2-D, on a screen, Rembert’s work has sometimes been mistaken for Lawrence’s. The philosopher Erin I. Kelly, who worked with Rembert on his memoir, first came across his pieces when she thought she’d found a painting by Lawrence in an online search. Seen as actual objects—which was recently possible from fall 2021 through winter 2022 in exhibitions at Fort Gansevoort in New York City and in a joint show at Adelson Galleries, with work on leather by one of his sons, Mitchell—the detail in Rembert’s work is riveting.

Working with a bevel, a pear shader, and an assortment of tools, some of which he made by hand, Rembert carved and rendered the tales of his life. He started with the settings—the hypnotic winding rows of the cottonfield, the places on Hamilton Avenue where he was welcomed with love. He painted scenes of his early life: Being given away as an infant by his birth mother to Lillian Rembert. The teacher who encouraged him to draw even though he didn’t make it to school often enough to learn to read (reading and writing would come later, in prison). Playing doll’s head baseball because no one could afford a real baseball and because they could name the head after a plantation owner. The cottonfields again. The backrooms of Hamilton Avenue businesses where NAACP and SNCC members met to organize. Climbing on a bus in 1965 with all the other young civil rights protesters to go to Americus about fifty miles away to risk their lives for the right to vote. Getting chased down an alley in Americus by two white men—and jumping into a car to get away.

"Chain Gang Picking Cotton" 2005. Dye on carved and tooled leather

Winfred Rembert was jailed in Cuthbert for taking that car for his survival in Americus. He was nineteen. He suffered a beating at the hands of a sheriff’s deputy, managed to wrest the deputy’s gun away from him, and escaped, only to be turned in by a couple in town he thought could be trusted. He was returned to the Cuthbert jail. Before sunrise, a mob of white men removed Rembert from his cell, drove him into the woods, violently stabbed and beat him, and hung him from a tree. The lynching was stopped by a faceless someone whose identity he never learned, a man he refers to in his painting as Wingtips, for the distinctive shoes he wore. “Carry him on back to the jail. He gonna die anyway,” Winfred remembers Wingtips saying. Back in his cell, for days Rembert squeezed a t-shirt tourniquet over the grievous knife wound he suffered at the hands of the mob. He ultimately served seven years of a twenty-seven-year sentence, much of it spent working on chain gangs. And for a long time afterward he spoke to very few people about what he had endured and what he had narrowly escaped. When he finally told Lillian Rembert, he recalls in his memoir, “it was like I’m telling her out of a movie or something. Mama, this really happened.”

“They took him for what they call ‘a ride,’” Patsy Rembert said this past fall from New Haven, just two seasons after Winfred passed away in March 2021. In a virtual talk organized by the Schomburg Center for Research in Black Culture, she spoke with Erin I. Kelly, who interviewed Winfred and revised his book with him, and author and curator Nicole Fleetwood. “They took him out in the woods, down a country road,” Patsy recalled. Decades after his near-lynching, Winfred had directed her and their friends Phil and Sharon McBlain along the same route. “Even though they had him in the trunk of the car, his memory is so good. He remembered every corner, every turn.”

“It put a mark on him,” Patsy said. “It put a mark on his heart and his mind that he could never forget.” Cuthbert, Georgia, is a four-hour drive west of Brunswick, the town where unarmed Ahmaud Arbery was pursued and killed in 2020 by three white men. Without the proof of a graphic video, and continued pressure by activists and the Arbery family, it is likely that no charges would have been brought against Travis and Gregory McMichael and William Bryan, all recently sentenced to life in prison for felony murder and other charges. In the Schomburg Center conversation, Patsy recalled the stark truth of rural Georgia in her childhood: “There were more people dying and they wasn’t being recorded. They would take you and lynch you and you would come up missing. And nobody knew where you was... Who are you going to tell, somebody’s done something to my brother or my husband?” She believes that Winfred’s life was spared so that he could tell his story, an eyewitness video unfolding on leather. In his depictions, Winfred painted what his face looked like in the rearview mirror on that long dark ride, the wingtips he could see on the ground from where he hung, and, unspeakably grim in Almost Me, his own body as Wingtips might have viewed it in the moments before his life was spared: shirtless, the rope belt on his pants nearly matching the one they’d tied around his neck.

Winfred Rembert had exhibited his leather paintings since the late 1990s, and as the story goes: he slipped into a meeting of the Yale Graduate Club and at the end of the proceedings, boldly stood up, introduced himself as an artist, and unrolled one of his works. He had his first solo exhibition at Adelson Galleries, in association with Peter Tillou Works of Art, in New York City in 2010; in 2015, he was honored by Just Mercy author Bryan Stevenson’s Equal Justice Initiative.

I met Winfred and Patsy in Chicago in March 2017 at a gathering for new and recent recipients of the United States Artists Fellowship, an unrestricted award of $50,000. Some of the other recipients had been Claudia Rankine, Stanley Whitney, Miranda July, Shirin Neshat, and Charles Atlas. The honorees also typically include fine artists doing transformative work in crafts-based media—quilters, potters, fiber artists. When I first saw Winfred in a banquet room full of other artists, he stood out, not so much for the way he looked as for the way he looked at everyone else. I recognized him as someone who had lived multiple other, infinitely more dangerous and complicated lives than most, visibly sussing out the people in the room for their realness, determining who to trust, and how to be. Winfred was naturally, refreshingly gregarious, but he also had learned to survive by a kind of sublimation and performance when necessary.

All Me II, one of his most haunting works, depicts dozens of uniformed men working on a chain gang. Its composition is as dizzying and disorienting as some of his cotton fields, making it almost impossible to tell where one human body ends and another begins. It is an infinite self-portrait. “You have to play a role that isn’t really you,” Rembert writes in Chasing Me to My Grave. “It’s like slavery. You have to meet all those demands and keep a sense of yourself as well. You don’t want to be identified with any of the roles you have to play, so you are all of them. It’s like all of you and everybody else around you are all tied up into one.”

Winfred and I talked a lot over those few short days. Deana Haggag, then the president and CEO of United States Artists, told me Winfred said to her that I made him feel safe. The day we met, he spoke to me about making his paintings. He told me about the prescription medication he’d begun taking to stave off the nightmares that still terrorized his sleep. He told me he’d recently started envisioning a book on his life. Picking cotton as a boy, he was lucky to have made it to school a couple days a week, never enough to stick. In prison in the ’60s he’d finally learned to read and write.

These skills came in particularly handy in 1969, when he first fell for Patsy. He had seen her going to set plants while he was out on a work crew one day. Undeterred by her reluctant parents, he wrote her devoted love letters in perfectly drawn cursive. He was enlisted to write letters on behalf of other incarcerated men—to their wives. And he started to write in an effort to free himself: “I wrote letters and dropped ’em on the ground, hoping someone would mail them from jail,” he told me. “I’d address them to Martin Luther King, Jesse Jackson. Nobody believes you are innocent. Nobody believes that a man can go through some things, and still be alive.”

Patsy and Winfred married in December 1974, after his release, and that winter began the first of a series of moves between different cities in the North with occasional visits to Georgia. When Winfred died in New Haven on March 31, 2021, Patsy, his wife of nearly forty-seven years, was by his side.

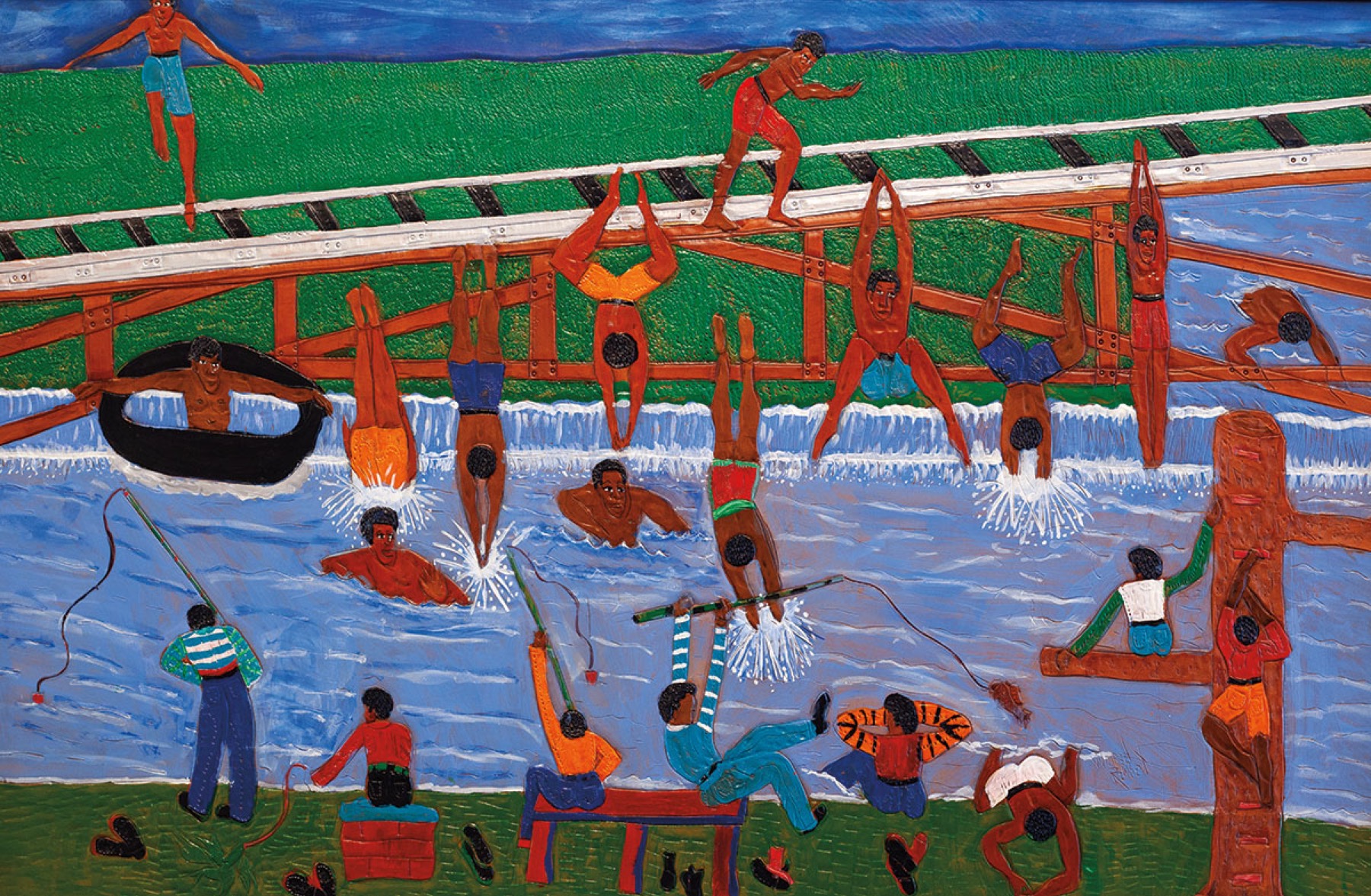

"The Curvey" 2013. Dye on carved and tooled leather. All works courtesy Fort Gansevoort, New York ©2022 Winfred Rembert / ARS NY

After the awards banquet in Chicago, there was a gathering at a small club—after-party performances by some of the artist-fellows in attendance. Most everyone was still dressed up from the awards ceremony. Winfred wore a matching oversize shirt and pants in a deep, almost purple brown, a shade particular to stylish men of a certain age. Patsy had stayed back at the hotel, but Winfred was eager to hear some music, performed by some of the honored artists and others. We sat on chairs pushed back against the walls of the club, and Winfred drank Coke and water. He told me how, back in prison days, he’d once come up on a group of men singing “My Girl” together in the yard. “That’s not the way that goes,” Winfred told them, and proceeded to show them how to sing it. At home in Connecticut, he would wander over to the liquor store and sing with whoever was gathered outside. He also sang with several other groups and at church. “When he was a deacon at that Sanctified Church, people came at him like he was a star,” Patsy remembers in Chasing Me to My Grave.

During the show I tried not to laugh at Winfred’s commentary, a little too loud, but also a little too spot-on, like taking your wise-cracking grandpa out for the evening. “He’s just making that up as he goes along, isn’t he?” Winfred said to me, of an avant-garde violinist who, to be fair, was performing an improvisational composition. After a little while of this, Winfred sighed, “What, he’s got more songs?” He perked up a little when a performance artist, a dancer, came on. “Oh no she don’t!” Winfred said, even louder, when the dancer slipped off her robe, stripped down and continued, in just pasties and her underwear. “I give him a zero, but I give her a one.” And then he raised his hand. He asked if there was time for another song. There was a set lineup, the emcee explained, but Winfred raised his hand again.

Winfred’s knuckles were still knotted from work on the chain gang and fighting in prison; he’d weathered numerous physical wounds from the attempted lynching. It was late and it had been a long day. To others in the room who didn’t know his story, it probably just looked like signs of age as he stood up, steadied himself, and walked with considerable difficulty across the room. Certainly, they didn’t know that back in the day, he’d once been asked to join the Soul Stirrers on tour. Winfred took the microphone. He proceeded to make a dedication to his son Edgar, who had died while playing football a few years earlier, at the age of thirty-seven. As he began to sing, his voice cracked a little, choked, but then smoothed on out.

Winfred said the song he would sing was “Daddy Come Home”—it’s actually “Daddy’s Home,” a song written and originally performed by the doo-wop group Shep and the Limelites. But I didn’t know any of that then. As Winfred began to sing I recognized it from the Jackson 5 and solo Jermaine Jackson covers. But mostly I just listened.

Daddy’s home, Daddy’s home to stay

It wasn’t on a Sunday (Monday and Tuesday went by)

It wasn’t on a Wednesday afternoon (all I could do was cry)

I made back to you

How I’ve waited for this moment

To be by your side

Later, I’d learn, “Daddy’s Home” had also been covered by Junior English, the Carpenters, and many more. Winfred’s lyrics that night were a slight deviation from the first known recording. Shep and the Limelites’ version was a Billboard number two, behind Ricky Nelson’s “Travelin’ Man.” That was in May 1961. Winfred would have been sixteen. Maybe he’d first heard “Daddy’s Home” in the pool room on Hamilton Avenue where he worked, or at the juke joints nearby, over at Cat Odom’s Cafe or Bubba Duke and Feet’s or Black Masterson’s place or Sadie Mule’s, or the Big Apple Tea Room, where they played Rufus Thomas, Gladys Knight, and James Brown on the jukebox, or Miss Annie Bell’s place, where a man named Poppa Screwball was the best dancer for miles around. I wondered, but didn’t ask, if it was a song he sang with the other men standing outside the liquor store on nights in New Haven and Bridgeport.

“I shouldn’t have said that about my son,” he told me after. “It made me not be able to do it right.” But the room was floored.

Patsy lit up when a question I’d typed into the chat was read to her. I still thought about Winfred’s singing after that night, and I wanted to hear more about that part of him. “He was very talented. He could have went professional in singing,” she said. “But he refused to leave home because he said he couldn’t raise his children on the road....He chose to stay at home.”

At the close of the online talk, in the last moments as most people in the audience were signing off, a photograph of Winfred suddenly popped up on the screen. I had seen it before, on his website—it’s Winfred standing in a doorway with a hat on and a warm, mischievous grin on his face, pointing at the camera, a kind of “here’s looking at you, kid.” Surely it was Patsy’s Casablanca moment. She was visibly overcome. “Honey, I see you!” she said into her camera, leaning forward as if she could touch his face. “I see you, honey, I see you!” Earlier, she had told the audience that she had never expected that Winfred would go before she did. “Yes, you’re pointing at me, I see you! Oh, I love that man. I love him so much. And you did sing me a song ... ‘[Lady], My Whole World is You.’ I should have been singing it cause my whole world is him.”