Pigskin

By Kristen Arnett

Illustration by Michelle Garcia

The blue Honda swerved onto the curb, almost clipping the women with its front bumper. They’d been walking hand-in-hand on the sidewalk, and the sudden intrusion of the car felt like an unwelcome guest butting in on a private conversation. Bailey screamed and dropped her bag. Gina swore at the driver, who sped off down the street, nearly rear-ending a silver Mercedes attempting its fourth try into a parallel spot.

The car had a domino’s sign haphazardly attached to its roof that flopped over when it turned the corner at the end of the block. Then it was gone, out of sight. All that remained was the lingering stench of burnt rubber.

“Hope the crappy pizza is worth it,” Gina said. “All that drama for something that costs less than twenty bucks.”

“That scared the shit out of me.” Bailey pressed a palm to her chest. Her fingernails were painted bright green. They matched the jeans she was wearing; radioactive neon, tight ones that cut off well above the ankle. Gina had made fun of her when she’d picked her up for their date. You look like a string bean, she’d said, and Bailey rolled her eyes and said, Don’t you mean the Jolly Green Giant? Bailey was taller than Gina by several inches and liked to rub it in.

“It’s okay.” Gina was practical. The car had almost hit them, sure, but it hadn’t. The crisis had been averted. They could go about their evening, no problem.

Bailey rubbed at her face, smearing her lipstick. It was a nervous tic. “That was so scary! Why aren’t you scared?”

“We’re fine,” Gina said, because she always talked about them as a couple and not individual people. Bailey could sometimes be dramatic about things. She jumped at loud noises and cried over sappy humane society commercials, but Gina didn’t really care. It was part of what she loved about her girlfriend. Nothing was ever boring, and her girlfriend was sweet. She took Bailey’s hand again, and they continued walking. They were headed to a pop-up pizza place in downtown Orlando. The slices had things on them like ghost peppers and pickled red onions. Gina wasn’t convinced the food would be any good, but she said she’d try it once, for Bailey, who didn’t eat meat. They could never find a restaurant they both liked. Downtown was full of high-rise buildings, mostly banks, but there were still a few eateries to choose from that they hadn’t tried yet.

“I could’ve had a heart attack.” Bailey struggled with the strap on her purse, which was more of a satchel, overloaded with things she never needed but claimed she might someday use: a mini umbrella, a travel toothbrush, some incense, a pack of playing cards. Gina took the bag from her and slung it over her own shoulder. Bailey was always complaining about back pain, and the oversized bag really wasn’t helping matters.

“You’re thirty-three years old. You’re not gonna have a heart attack just because some asshole jumped the curb."

"Women in their thirties have heart attacks all the time. The statistics are crazy.”

Gina knew that Bailey had no idea what she was talking about. Whenever she used the word “statistics” in an argument, it meant that she had seen a headline once about it and never actually clicked the link. They’d been together for a year and a half, but to Gina it felt like a lot longer. Longer in a nice way, like they’d crawled into each other’s heads and gone through the brains’ filing cabinets that stored their wants and needs. The image made perfect sense to Gina, who was a branch manager for a chain of office supply stores.

They stepped down into the street for a moment to avoid a large, mucky puddle, then passed it and hopped back up onto the sidewalk again. Buildings loomed over them, large and gray and mirrored. It was a very Orlando thing, Gina thought, to be surrounded by banks and big businesses and find a tiny restaurant shoved in between, like discovering a sentimental birthday card hiding inside an outdated and oversized encyclopedia. Gina adjusted the strap of the bag on her shoulder. It was beginning to cut into her skin.

“Your hair looks cute that way,” Bailey said. “You should wear it like that more often.”

“What way?” Gina asked, genuinely confused. She was wearing her hair the same way she always had: It was dark and short, slightly graying, and parted severely to the side. Before Bailey could answer, a piece of metal fell from the sky and struck her directly on the head.

For Gina, the rest of the afternoon was a blur; a smear of almost-moments that felt like glancing out the window of a moving car. The ambulance ride to the hospital, the paperwork and the relentless questions—none of it stayed, except the moment when the chunk of metal hit her girlfriend’s skull. Hard hitting soft, like a fist into a baseball glove, but deeper. It was a sound that Gina had never heard before. She hoped she’d never hear it again.

But she did hear it. Usually when she was lying in bed, in that twilight space of half-awake before the night took her. The thump would come then, that awful sound, and she’d sit up and look at her bedroom ceiling, as if she might spot the hole where a lump of metal had come falling through. But there was nothing. Just her, the lonely room, the bed, her stuttering breath. Bailey did not come to her in dreams. Not the girlfriend of before and not the nightmare version she’d feared would appear—a bloodied one, the body she’d seen crumpled on the sidewalk. It had been weeks, but Gina still felt like she was standing back on that curb, headed for pizza, reaching for her girlfriend’s hand.

Bailey’s bag was sitting in Gina’s living room. She’d placed it on the dining table when she’d finally made it home from the hospital. Bailey’s parents had shown up after a few hours. They lived in Micanopy, near Gainesville, and it had taken a little while to track them down. Gina had found their numbers in Bailey’s cell phone. It was easy enough to unlock since Bailey used the same code for everything because she was so forgetful, 4443, the street number of the house she grew up in. Gina had looked for mom and dad in the contacts and had finally found them listed under their given names. The Jensens weren’t exactly close with their daughter, and they had no idea who Gina was, even though Bailey had said she’d told them about the relationship after their very first date.

I knew we were going to get married, Bailey said, laughing and sipping from a lukewarm bottle of beer. I told them I’d found my future ex-wife.

Mrs. Jensen had a face like a startled bird. Her husband looked similar. They didn’t bear much resemblance to Bailey, who had white-blond hair and brown eyes she rimmed with heavy black eyeliner, but Gina supposed some of that was the fact that Bailey always dressed like she was in an aerobics video from the 1980s. Dyed hair the texture of cotton candy, hues skewing either blond or bright red, clothing in wild prints and colors, an intense amount of vibrant makeup. In contrast, Gina thought Bailey’s parents looked like they’d been dipped in khaki paint. All beige. All neutral. Nothing vibrant and exciting. Even their voices had sounded dim, as if they were speaking to her using vocal cords that held nothing but white noise.

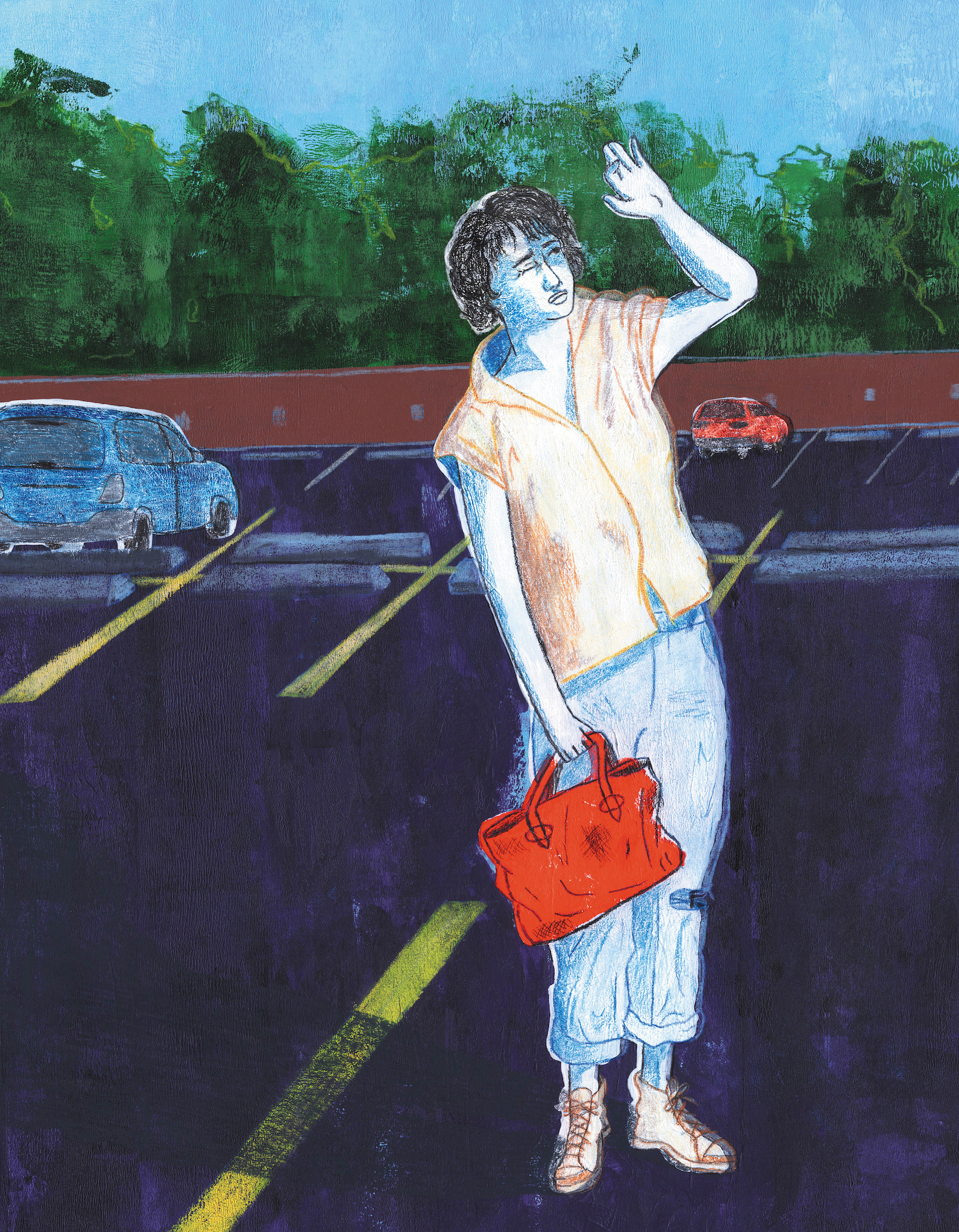

The Jensens hadn’t known who she was, that was one bad thing. But then the hospital staff told her that it had to be “family only,” meaning not Gina, who was no longer welcome. So, she’d walked out of the hospital and stood shell-shocked in the middle of the parking lot, staring blankly out into the early morning’s melon-pink sunrise. Stood and stared until a car honked at her, woke her from her stupor, and she stumbled to a grassy patch beneath a tree and wept. She hadn’t realized she still had Bailey’s bag until she’d called a car and finally made it back home.

Home was her own apartment, five miles away from Bailey’s apartment, because they’d both valued their privacy and wanted separate space. Recently Gina had regretted that decision. She’d wanted to bring up moving in together, kept meaning to do exactly that, but had put it off. They were happy. She hadn’t wanted to wreck it.

But everything was irretrievably wrecked. Was Bailey dead? Basically. She had permanent brain damage; a ventilator was the only thing keeping her alive. Where had the metal come from? When she’d asked a nurse about it, they’d procured a form. It said that the recovered item—which had been collected by an EMT at the scene—was a broken chunk of a metal bracket. But falling from over twenty floors up, it was considered a deadly weapon.

Weapon? Gina asked the nurse, and the nurse had leaned in close, as if they were conspirators. The Jensens could file a civil suit against the building manager.

They’d win millions, guaranteed, the nurse stated, nodding importantly. She had what appeared to be a chocolate stain on the front of her scrubs, which were pink with a rainbow teddy bear print. For a few weeks, Gina came on her lunch break to see her girlfriend, whose eyelids were taped closed with gauze and translucent medical tape. There was a bandage obscuring the top of her head, with a little fountain of bleached hair poking through the wrap. Gina thought Bailey would have loathed the room, which was sterile and plain and white, but when Gina brought a bouquet from Publix, Mrs. Jensen told her that Bailey was allergic and it might complicate things.

Gina wasn’t sure what things flowers might complicate, since her girlfriend had never shown any allergy symptoms in her presence. In fact, she’d kept fresh bunches in every room of her apartment, buying them weekly from a vendor down her street. It felt pointless to argue over it, though, since Bailey would never know the flowers were there, so Gina merely took the bouquet home and placed it on the dining table, next to Bailey’s bag. Gina had been in the process of throwing out the now-dead flowers when she’d gotten the call from Mrs. Jensen telling her that Bailey had “passed on.”

Passed on, as if her girlfriend had been asked if she’d like some dessert and replied, no thanks, I’m full. The image prompted a kind of hysteria in Gina, and there were a few tense moments in which she worried she might burst into laughter, but she pinched the skin of her inner arm and managed to ask about the service. Mrs. Jensen said there wouldn’t be one.

“But how will I see her?” Gina asked, which wasn’t the right question. Bailey would never be seen again. Mrs. Jensen acted as if Gina hadn’t spoken and continued talking in that same monotone. After a few more awkward pleasantries, the phone call ended. There Gina sat with her dead bouquet and the bag that wasn’t hers.

She tossed the flowers into the trash and went to the bathroom to splash some water on her face.

“Get a haircut,” she told her pale reflection. It seemed important that she do that, get the haircut, because the last thing Bailey had said was that Gina’s hair suited her. It had grown out a lot in those several weeks. In its current unkempt state, strands kept falling down into her eyes and the back was curling over her collar. She drove to the closest haircutting place, which was a barbershop located in a strip mall next to a combination Pizza Hut and Taco Bell. She’d never gotten a haircut there before. She usually got them from her friend Ruth, who styled Gina’s hair in the middle of her living room while they drank white wine and watched old episodes of Laverne & Shirley. She hadn’t called Ruth to ask about a haircut because she didn’t want to be asked about Bailey. The thought of sitting there while her friend carefully trimmed her hair and asked her how she was holding up felt like too much to bear.

The barbershop was a sports-themed place that catered to men. Instead of regular waiting room chairs, a small, uncomfortable-looking set of bleachers had been pushed up against the front wall. All of the employees were women. They wore black-and-white-striped jerseys. Gina sat on the front row of the metal bleachers and set her keys down beside her. They made an awful clanking sound so she picked them back up again and rested them awkwardly in her lap.

“Do you need help?” asked the woman with the only empty barber chair. I need something, Gina thought, but she was unable to articulate exactly what that something was, so instead of answering she followed the woman back to her station.

The seat was shaped like a normal stylist’s chair, but the fabric felt weird and kind of pebbly under her hands, so Gina commented on it.

“It’s made to feel like a football.” The woman’s name tag read Cindy and there was a baseball dotting the “i.” She flipped the bright red haircutting cape over Gina’s shoulders and tucked it in snugly before spraying down the back of her head. “You know, pigskin.”

“Sure,” Gina replied, though she wasn’t sure she’d ever touched a football in her life. It seemed crazy to think that she hadn’t. She was going to be thirty-six that year, and it would be very weird for her to have gone her entire life never touching a football. Maybe she’d thrown one in school? But that didn’t seem right, either. She had two younger sisters and neither of them were athletic. Her dad had left her mother when Gina was only eight years old, and he’d never watched football. Only golf, which had bored Gina, so she’d left the room whenever it was on the TV. Had Bailey liked golf? Or football? Any sports?

“I’m going to be thirty-six,” she announced, and burst into tears.

“Oh, honey, that’s not so old.” Cindy rifled through her drawers and produced a blue microfiber rag that she handed to Gina to use as a handkerchief. “I’m gonna be fifty-three this year and that still feels young to me.”

The rag smelled strongly of Tide detergent, a homey scent that comforted Gina. She told Cindy that she wanted the exact same haircut, only shorter, and while the woman snipped and trimmed, Gina stared at her own pallid reflection and thought about the fact that Bailey would never have a haircut or a birthday again. No lemon cake with sparklers, no multicolored streamers cluttering her apartment for the entire month of June, sagging over the bathroom doorway and catching on Gina’s shoulders when she got up in the middle of the night to pee.

“How’s that, sweetheart? Better?” Cindy asked. Gina smiled and nodded, though she hadn’t even looked at her hair. She paid in cash and left a very big tip, sure that the woman would go home and tell her family all about the weird lesbian who’d cried all over her red cape. It was the kind of story Bailey would have come home with, Gina thought. Bailey had worked in a convenience store. She had a lot of regulars who acted like she was their therapist.

They think you wanna hear their entire life story, she’d complained, her head pillowed in Gina’s lap while they watched a terrible made-for-TV movie. I swear, I should put a psychiatrist’s couch by the Big Gulp machine and charge money.

Gina got in her car and examined her hair in the rearview mirror. There was a cowlick sticking up in the back that she didn’t remember having before. She sat there paralyzed with fear, worried that she’d gotten a different haircut than the one she actually wanted, accidentally obliterating her last memory with Bailey.

Someone knocked on her window and Gina jumped. It was Cindy. She was holding up a cell phone.

“This yours?” she asked, waggling it back and forth. “Your phone?”

“No,” Gina said. She pointed to her own lying face-down on the passenger seat.

“Okay, sweetheart.” She tapped a bright pink acrylic fingernail against the glass. Three staccato clicks. “Thirty-six is gonna be a good year for you.”

Gina nodded. Cindy waved goodbye and followed a tall, lanky man in a gray business suit back inside the barbershop. When Gina got home, she tossed her keys onto the dining table next to Bailey’s bag. There was a part near the front clasp that was nearly worn through. It was a faux leather bag that Bailey had gotten at Target before they’d started dating, and she refused to replace it even though it looked beat to hell and back. Those were the words Gina had often used to describe it, beat to hell and back, as if it had somehow lived through an apocalypse. She’d gotten Bailey a nice new one as a surprise, bright yellow leather with rose gold clasps, but Bailey never used it.

I like what I like, and I don’t like that, Bailey said when Gina had asked why it sat untouched in Bailey’s bedroom closet.

You like bright colors, Gina argued. You love that clowny stuff.

That’s not all I like, she replied tersely, and Gina hadn’t bothered asking again. She told herself she’d think of a better gift in the future.

But there was no future, just the same beat-up shitty purse. No more girlfriend. Gina poked the bag with her finger and it barely budged, so she jabbed it a little harder. It folded in on itself, crumpling like a jack-o’-lantern that had started rotting from the inside out.

“I hate you,” she said, and she wasn’t sure if she was referring to the bag, to Bailey, or to herself. She punched at it and it slid off the side of the table, hitting the floor with an unimpressive splat. It reminded her of the piece of metal thwacking her girlfriend’s head, that awful thunk, and she wished she could undo everything, every single part of the past month. She got down on her hands and knees to pick up the things that had spilled from the bag’s open top.

Strange how a purse could hold so much detritus of a life, Gina thought. There were several lipsticks in mint-green tubes: coral, flamingo pink, sunset orange. A fistful of linty pennies. Bailey’s wallet, a tacky Velcro thing with a bejeweled palm tree embroidered on the front. Dozens of graying CVS receipts. Those were only the things that had spilled out; the bag held much, much more. She opened it and peered inside, staring down at the mix of trash and valuables. Her phone buzzed on the table overhead. When she got up from the floor to answer, Bailey’s mother was on the other end of the line. “I’m sitting in my daughter’s apartment, and I don’t know what to do.”

After that, there was nothing but measured breathing, in and out. It didn’t sound hysterical or panicked. It was quiet. Peaceful. It reminded her of those meditation recordings her girlfriend used to play on YouTube. Gina, who felt like a ball of knotted muscles, began to relax. She breathed along with the woman, heart rate slowing, slower, until her eyes closed and she realized she was on the verge of sleep.

“Can you come over?”

That woke her up. “To Bailey’s apartment?”

“Yes.” Another long pause, more breathing. “I need help.” Gina looked at the bag, refilled again, sitting limply on the table. Bailey’s driver’s license was still inside it, along with most of her important paperwork, including her Social Security card. Bailey had carried that stuff around with her everywhere, always nervous she’d lose it if it wasn’t on her body. She was the kind of person who worried about having her Social Security card stolen but used the same log-in password for every single website, including her online bank account. They were so different from each other in that regard, Gina thought, but it was what had made their relationship so refreshing. She never knew exactly what her girlfriend might do next. “Okay,” Gina said. “I can bring you Bailey’s purse.”

“Thank you,” Bailey’s mother said, and hung up the phone. Gina put on a clean shirt because she realized that the one she was wearing had ketchup on the front and she couldn’t remember the last time she’d had any. Was it with Bailey? She wasn’t sure. She wasn’t sure about anything anymore. She picked up her car keys and Bailey’s bag and locked the door behind her.

***

Bailey’s mother’s name was Linda. Gina remembered it on the drive over, caught inside another memory. They’d been eating frozen yogurt in the park near Gina’s apartment, watching a young girl with yellow barrettes in her hair run wildly around the fountain. She was dipping her fingers into the clear blue water every few seconds, laughing, while her mother yelled something about staying clean, that there could be parasites.

Sounds like Linda, Bailey had said, shaking her head. My mom thinks every drop of water in Florida has got amoebas. She’d put gummies in her frozen yogurt and was having a hard time chewing them. She kept complaining about how they hurt her jaw. Gina asked why she’d chosen gummies when there were so many other toppings, better ones to match the flavor of the yogurt, and Bailey said that it tasted fine to her. She’d never finished that yogurt. Gina had thrown it away for her, a cup of soupy vanilla cream swimming with gloopy gummy bears.

Linda answered the apartment door wearing what looked like the same beige outfit that Gina had seen her in at the hospital. It looked clean, she thought, and was neatly pressed, and her hair was the same beige nothing color. Dishwater blond, Gina thought, the term popping into her head out of nowhere. It wasn’t a term she’d known before she’d started dating Bailey.

“Oh, thank God,” Linda said. She was holding a silver mug with a golden unicorn horn sprouting from the front. Bailey’s name was etched on the side in pink glitter.

“I bought that for her,” Gina said, pointing at the mug, and Linda looked at it as if she’d forgotten she was holding it.

“Do you want some coffee?” she asked, and Gina said sure, even though she didn’t really like coffee. She figured it would be better to hold something than not have anything to do with her hands. She walked inside and tried to breathe through her mouth. She hadn’t considered the fact that the apartment would smell like her dead girlfriend. Back when Bailey had been alive, Gina hadn’t thought her girlfriend smelled like anything. But now that Gina was in her apartment, surrounded by her things, she realized that Bailey had smelled like herself.

“Smells like King’s Hawaiian rolls,” Gina muttered, and wiped her eyes discreetly with the corner of her sleeve. She didn’t want to cry in front of Bailey’s mother.

Linda handed her a purple mug of steaming black coffee without asking if she took cream or sugar. They sat down together in the living room on Bailey’s pale pink leather sectional sofa. The knit throw, a blue and green thing resembling sea kelp, that usually draped over the back of the couch was bunched up in a wad on the glass-topped coffee table. Linda hunched in on herself for a moment, cradling the hot mug in her lap. Then she appeared to catch herself and sat up straight again, hair swinging back behind her shoulders.

“I spilled some coffee on it,” Linda said, nodding at the blanket. “I felt bad, but then I remembered... No one’s going to use it anymore.”

“Right.” Gina had placed Bailey’s purse between them on the couch. It bulged there, sitting upright like a pregnant pug.

“Now I have to go through everything. Choose what to keep, what to get rid of. But there’s so much.” Linda gestured with the mug, and some of her coffee slopped out onto the leather. She grabbed for the bunched-up blanket to wipe up the mess. She told Gina the blanket had once belonged to Bailey’s grandmother.

“That’s nice,” Gina replied, because she didn’t know what else to say.

“Yes.” Linda sat and stared at her mug. Gina hadn’t seen her take a single sip.

After an interminable length of silence, Gina cleared her throat.“Do you want to open Bailey’s bag?”

“Why?” Linda asked. “Is there a letter?”

“A letter? No, there’s not a letter.” Gina was confused by the questions. She shifted and set the mug down. She was not going to drink the coffee; it had been foolish to agree to a cup. “I just thought you might need her ID or her credit cards. So you can work out how to cancel things. Stuff like that.”

“Oh.” Linda set her mug down, too, and sat back with a sigh. “I thought maybe she’d have a journal, like she did when she was growing up, but I haven’t found anything.”

“Bailey didn’t journal.” Gina had never seen her girlfriend write anything, not even a grocery list. Once she’d scribbled down an account number on the back of a receipt and it had looked like she’d written the numbers using the wrong hand.

Linda looked at her like she was crazy. “Sure she did, ever since she was little. Six years old and she had a typewriter and reams of paper in her room, her dresser stuffed full of stories and poems and music lyrics. Spiral notebooks full of dreams she’d written down.”

“I didn’t know that,” Gina said. They’d never talked about books or writing. Gina realized she’d never once asked Bailey about her dreams. Bailey had asked Gina about hers, though. They’d woken at sunrise the morning after Gina had slept over for the first time, the light crawling salmon-pink up the far wall of the bedroom, uncovering framed art and shelves and potted plants that Gina had never seen before. Bailey had leaned over and pushed her lips against Gina’s ear.

You were kicking me all night. Fun dreams?

But Gina had been having a nightmare about her mother. She’d been yelling at her in the dream, and then she’d punched her mother in the face. There had been a spill of blood, some dripping between her knuckles. Gina hadn’t spoken to her mother in years. The dream had rattled her badly. But she and Bailey hadn’t been dating that long, and she didn’t want to scare her away, so she’d lied.

I never dream, Gina had said, and Bailey had gotten up to get ready for her shift.

“Okay, let’s take a look.” Linda set the bag on her lap and opened it. There was a collection of plastic pens, somewithout caps. A watch with a broken band. Bookmarks from the local library with the hours of operation printed on the back. And there at the very bottom was a teal notebook covered in spangly silver stars, pages warped from the pressure of a pen. Gina stared at it, incredulous.

“I knew she’d have it somewhere. Just assumed she’d stash it under the bed or in her desk, like she used to.” Linda flipped it open to the middle and Gina wanted to snatch it from her. But she just sat with her hands in her lap and watched Bailey’s mother flip through the pages. At certain points, she smiled. Sometimes she frowned. Once, she laughed, and flipped the book around to show Gina a fairly impressive drawing of a bullfrog with TOADALLY AWESOME written beneath it in scrawling cursive. Cursive! Gina had never even seen Bailey write anything in cursive except her signature.

“You never really know your child.” Linda set the notebook face-down in her lap and grabbed for Gina’s hands. Gina felt heat flood her fingers. She hadn’t realized she was cold, freezing. She wished she was holding the mug again, just for the warmth, but Linda wasn’t letting go.

“Do you have kids?” Linda asked. “Any babies of your own?”

Gina shook her head. Linda pressed her hands, sandwiching Gina’s between them.

“It’s like...when you have them, when they’re tiny babies, it’s like they’re sent from above. You learn everything about them. You just know...all of it. And then they grow up, and you lose it. It’s not fair.”

Gina looked around the room, taking everything in. One last look. There was the wicker basket they’d bought at a roadside stall when they drove out to Oviedo to look at horses one lazy Saturday. Multicolored Tupperware bins that housed a wealth of Publix grocery bags Bailey never remembered to recycle. A watercolor painting of a cheetah running across a field of tall grass that they’d found at a yard sale priced for eight dollars. Bailey had haggled with a man in paint-stained coveralls for fifteen minutes, finally getting the price down to a dollar seventy-five. When they’d left with it, stuffed in the back seat of Gina’s car, Bailey admitted she’d have paid double for it, even triple the original amount. When Gina asked why she’d bothered haggling for it, Bailey said, Sometimes it feels good to see what you’re capable of, you know?

“It’s just nice to have something. A little piece of who she was, so I can know her.” Linda got up from the couch and took their mugs into the kitchen. She left the notebook behind on the couch. Gina realized she could take it. Stuff it in the back pocket of her jeans and make a run for it.

She got up and looked at the painting of the cheetah. It wasn’t good art, though the frame was nice. Gina had said that to Bailey once they’d gotten it home, told her the work looked amateurish. The strokes were clumpy and hesitant. The animal’s face looked more like a mongoose than a cat. But there was something about the colors of it. All that bright, vivid light.

“Can I have this painting?” Gina asked Linda, who’d returned with two fresh cups of coffee neither of them would drink.

“You don’t want that,” Linda said. “It’s so ugly and cheap. I don’t know why Bailey even owned it.

“You don’t know us,” Gina said, and she really meant it. “You don’t know us at all.” She took the painting down from the wall and left with it.