Cosmic Requilting

A new exhibition by Sanford Biggers deftly remixes the patchwork of history

By Jodie Bass

Photograph of Sanford Biggers © Gioncarlo Valentine. Courtesy Speed Art Museum

Sitting down with the spry, sparkly, and multifaceted artist Sanford Biggers feels a little like catching Halley’s Comet in flight—a rare and spectacular event.

All the essential elements which formed him, akin to the ice, rock, and metallic dust that produce a comet, might not be considered exceptional on their own. Yet, both result in a powerful and resplendent force.

The youngest of three kids, Sanford grew up in the Baldwin Hills neighborhood of Los Angeles, back in the early Seventies, when the area was burgeoning. It was the preferred oasis of many Black luminaries. His house was filled with art objects and scupltures from the overseas dispatches of his seafarer uncle, McCoy Biggers. His dear cousin, John Biggers, a prolific muralist, was a magnanimous role model. Sanford often recounts the encouragement from early teachers which helped propel him along his course. His mother was also a teacher, his father a brain surgeon. It stands to reason that he thrived in academia, attending Morehouse College, Skowhegan School of Painting and Sculpture, and the School of the Art Institute of Chicago, then enriching his education with formative experiences in Japan, Italy, and Germany. Teaching is one of several languages he employs, currently as a visiting scholar at Massachusetts Institute of Technology. Painting, weaving, sculpting, and drawing are all hallmarks of his practice, as are writing, directing and performing music with the group Moon Medicin.

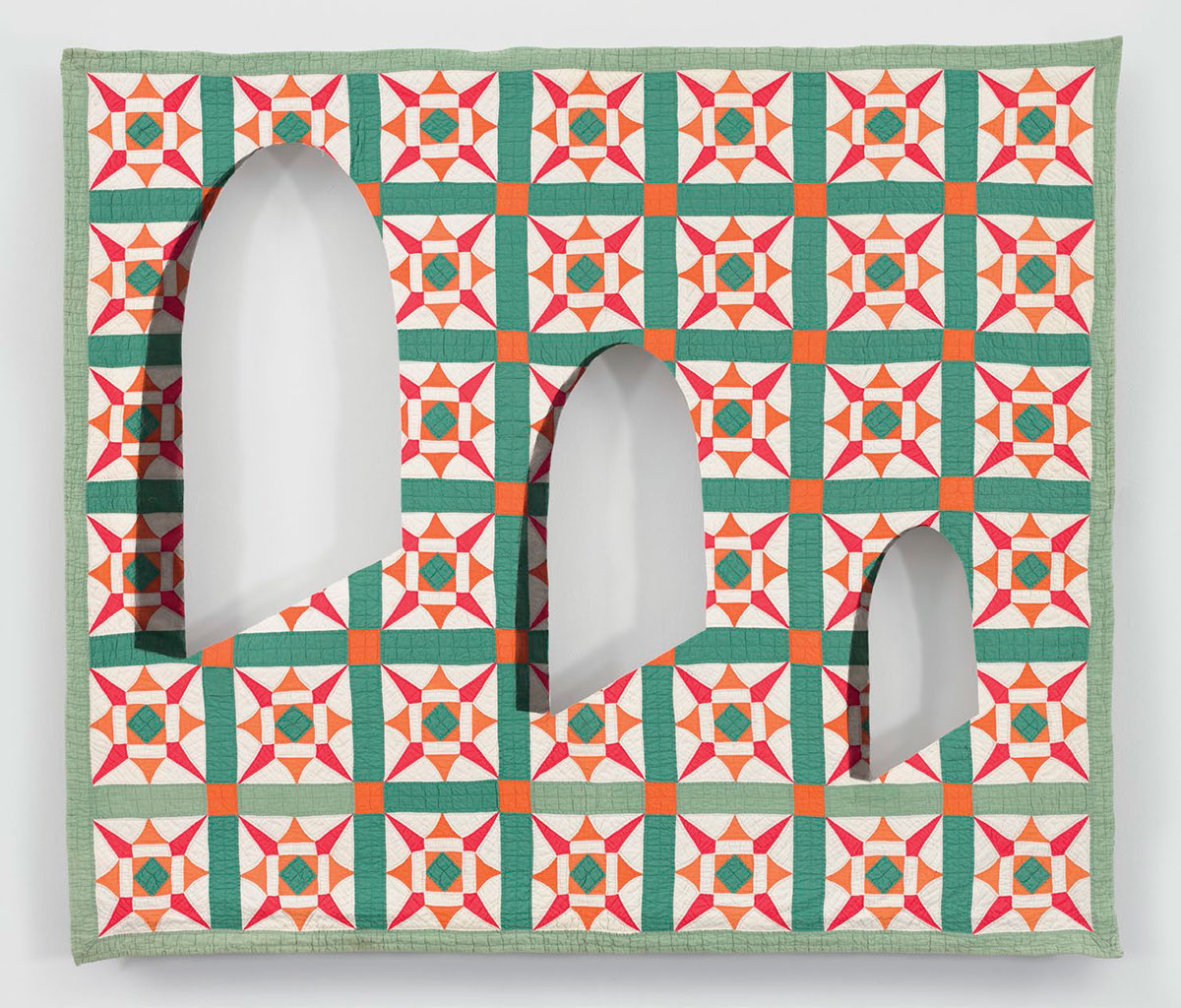

Codeswitch, at Louisville, Kentucky’s Speed Art Museum through June 26, 2022, is Sanford’s latest solo exhibition. Originally displayed at the Bronx Museum of Art, this third and slightly smaller show consists of thirty-one predominantly pre-1900 quilt-based works and two video works created over two decades of his career. The survey is a unique opportunity for visitors and artists alike to view these large-scale works hung together.

Having established an acute lexicon of symbols, deployed here in a series of quilt-based works called Codex, Sanford engages history like a shorthand. Even when communicating through salvaged and once utilitarian objects, his loose but evocative vocabulary remains nimble. Referencing difficult events from the collective past, he upends them; other times it’s enough to simply call them out. Like a chironomia, or classical gesture in painting, our deepest pathos are conjured. Societal issues are summoned, but rarely directly spoken. In other moments, with a simple and iconic arc of the finger, there is humor.

Playfulness, too, is key. Like in the current installation, hiding in one of the corners at the end of show, glistens Ooo Oui. She beckons me. From a delicate, masterfully embroidered, tiny-pieced, patchwork cotton quilt emerge dazzling sequins. A soothing hexagonal pattern subsumes triangulated edges, then becomes a Q*bert board of shimmering silver and black, and then again, a trap door, before morphing into a dark tunnel, just to keep you guessing. The piece overwhelms, an ethereal meteor shower of sensations, bordered by subtlety. By Sanford’s hand, pop references are somehow doused with the gravitas of Masonic secrecy, or a Voudou priestess’s spell.

Following the opening of Codeswitch in Louisville, Sanford shared a brief moment with me and the Oxford American to reflect on his path.

"Quilt 17 (Sugar, Pork, Bourbon)," 2013, antique quilt, assorted textiles, acrylic, and spray paint by Sanford Biggers. Courtesy the artist and Speed Art Museum

***

Jodie Bass: So my first question is: What can’t you do? Polyglot, polymath, multi-potentialed...

Sanford Biggers: I can’t sit still, creatively, that is. I hate performing and then being asked to speak, before or after it.

Musical performances?

SB: Yeah, or any performance. Frequently I am asked to do a sit-down after, and I’m like, “absolutely not.” It just doesn’t work for me. Because you have to be in a certain headspace to do a performance and to then shift that gear immediately, to analyze it for others, for entertainment, it just doesn’t work. What else? Time to sleep? I don’t sleep much.

Are you always working? How do you relax? Do you meditate?

SB: I started meditating again in the past two weeks. I used to do yoga all the time and meditate, sometimes simultaneously, sometimes separately. I stopped for a long time. I’m trying to figure out how not to work so much, but I get creatively antsy and work fuels me. When there’s no deadline or stressors, something I could probably do in twenty to thirty minutes could drag out for two hours, but it’s because I’m savoring being in that headspace.

Do you ever get tired of fighting the good fight? Are you exhausted or enthralled by all the potential details, down to each tiny knot, each stitch, the drive to capture and refract all these nuances? Do you accept fatigue as part of it?

SB: I do. It is part of it. Sometimes I feel like I just need to shut four or five of these things down and work in this one chamber for an extended amount of time and change my lifestyle and momentum to accommodate that. I have dreams of doing that. We’ll see when it happens, but I do think about it often, and I feel it’s coming sooner than later, to be honest with you. For many years I just had so much to get out.

Are you confronted with a need for self-preservation? To tease out responsibility from burden and, for your creative process, from the heaviness of history, in order to activate it?

SB: Well, I think that is part of that process. I often refer to it as frontloading my practice. Dealing with so many issues, regarding history and unrecorded histories, lesser-known histories, to put out a better perspective of the things we are taught.

Is intergenerational trauma in your parlance? Do you use the term, or does it resonate with you?

SB: It does, but in the sense that I think all humanity is going through intergenerational trauma. People often think that trauma is only felt by the victims, but I believe trauma is felt by the aggressors and the abusers as well. It’s a constant cycle. So on a psychic level, I think there is intergenerational trauma, but for all of us.

Back to that idea of “frontloading.” I wanted to be able to free myself from the burden of having to represent those ideas in perpetuity, because they’re already embedded in the work and the materials I choose, which allows me then to actually play a lot more. Like the show Codeswitch, there’s a lot of play happening there. All that heavy stuff is in there. But now it’s actually playful for me; it’s a way of rinsing the trauma off some of those ideas.

Where does your courage come from?

SB: Hmm, I think maybe being the youngest kid. My brother and sister are eight or nine years older than me and are really intelligent—academics, doctors, scientists, all that stuff. And as a kid, I had to sit at the table and listen to those conversations when I could barely pronounce the words and then find a voice—to speak with them and have an opinion. Also to break from it, I was the black sheep. I went into a totally different field than any of them.

Were your parents supportive early in your career?

SB: They didn’t know what to make of it at first. But a few things happened when I was very young: I won an art contest that sent me to Washington, D.C., to compete on a national level with other young artists. And my high school picked me to do an exhibition in the middle of the entrance of the high school. I don’t recall there being a series of art exhibitions in the lobby before, but for whatever reason, they picked me to put some oil paintings up. Those were gestures of faith that made me feel like, oh, there’s something to this and kept me moving forward. My parents started to see that too and became supportive.

Travel clearly informs you and your work. I’m wondering if taking the journey with Codeswitch from the Bronx to L.A., and now here to Louisville, has brought any particular reflections or experiences to the surface. Any noticeable differences in having your work circulate through these places? Has your own reading of your work shifted at all in the process?

SB: Every time I see this show, it shifts. I end up rediscovering the artwork. Also, in trying to retrace my steps in making some of the pieces, I’m totally confused and confounded at how I got to some of the results. I have a real desire to retrace those steps because I want to be able to do a particular thing again. It would be different, of course, but I want to set up those conditions for it to happen again.

The piece Hat & Beard, for example, took over a year to do. You can see the layers, how worked that piece is, because it took a lot of time to make sense of it all.

Seeing this show travel from place to place has been really satisfying. I have a personal connection with the Bronx Museum. Obviously, the Bronx has a relation to hip-hop, and I think there’s a lot of hip-hop in those quilts: sampling, chopping, screwing, cutting and pasting, scratching, all that’s in there.

When it went to L.A., that was a homecoming... [The California African American Museum] was where I used to take classes as a kid. One of the most influential shows that I witnessed when I was fourteen was when John Biggers, my cousin, had a solo exhibition, and my family and all our friends—the community—attended. That was one of the first times seeing an artist that I had a connection with do this. So Codeswitch was really satisfying to show there.

And showing here in Louisville, because I had a couple of experiences at the Derby in 2011 or 2012 that informed a lot of the Codex, like the seersucker and dandyism of Southern gentlemen. Fascinators and the whole fashion sense of Derby. The literal striation of looking at Churchill Downs and saying, this is Society, happening right in front of you, the good, the bad, the ugly, the inequity. But with the bourbon and sugar all on top of it. There was something poetic and strange, and sort of cruel, and I was influenced by that.

Is this the final stop for Codeswitch?

SB: It is as far as I know, but there are other shows featuring certain aspects of the quilt series.

"Ecclesiates I (KJV)," 2020, antique quilt, assorted textiles, and wood by Sanford Biggers. Courtesy the artist and Speed Art Museum

What do you think about when I say the South with a capital S? What does it mean to you and what does it mean to your work?

SB: I think red clay, I think bottle trees. I think Jim Crow, seersucker, grits, and humidity. When you get off the plane in the summer and your clothes stick to you. I think of fishing for crawfish with bacon fat, salt pork, on a string. I think of the outhouse at my grandparents’ house because it was that old. I remember where they lived didn’t even have a sidewalk when I was a kid.

Where was that?

SB: That was outside of the Third Ward in Houston. My dad’s place.

I think of civil rights, obviously. I think of cotton, of the original sin of the U.S., the whole “peculiar institution.” And how that’s really American history. It’s not African American history, it’s not white, it’s American history. It’s the backbone of everything that’s happened here.

I think about the amazing friends and moments I’ve had in various places here. Thankfully I haven’t had any extremely harrowing experiences. I’ve had worse experiences in L.A. and even abroad than I’ve had in the South. But I always have my radar on.

Do you find yourself code switching, still?

SB: I mean, I think we all do it to some degree. It’s just a natural aspect of human nature. There are a few people who probably don’t have to code switch as much as others.

I mean, it’s almost like it’s part and parcel now, right? Navigating so many different spaces...

SB: It doesn’t have to be an extreme thing. It doesn’t have to be a denial of yourself. I’m always the same person.

I almost like the switch sometimes. You can use it as a strength or as a weapon. All of us who’ve had to do some shifting to survive know that.

I’ve noticed you have an acute awareness of the temporal continuum, the lifespan of your pieces and body of work. You’ve referenced the layering of cities ancient and modern, building over and over and to later unearth and rediscover or marvel. It’s made me think of Confederate sculptures and other public emblems with less than desirable human legacies, some of which have been recently removed.

Have you ever thought of borrowing these statues for repurposing? What sort of purpose could we reassign in assembling an object graveyard like that?

SB: I would work with a repurposed monument, or memorial, for fun. I have recently been thinking about reclamation and erasure. For a project in Wisconsin at the Chazen Museum I am looking at the emancipation sculpture of Abraham Lincoln, where I sketched out a bunch of ways of recomposing it. I realized that I am more interested in inviting other artists to come and respond to the piece, however they want to. I’m asking poets, actors, dancers, visual artists, and chefs to respond, and then I will collect and share them. Because I think we all must find our own way of reconciling and making some sense of those monuments.

It’s not just the people who are negatively affected by them, but the people who supported them. They need to be in the conversation too. The conversation is the most important thing really. At the end of the day we can’t keep those monuments up, but we can’t hide them either.

I thought what was happening in Richmond, Virginia, was beautiful. Watching that sculpture change day to day, between the projection mapping, the graffiti, and the people around it, there wasn’t one final solution. Of course, it ultimately gets removed, but it still lives. The archive of all things that occurred with it is just as important as the monument itself. [In June of 2020, Richmond crowds toppled the Jefferson Davis monument. The city removed three other Confederate leaders’ statues after crowds covered some in ever-changing, artful graffiti.]

Is the confrontation of strangeness something you seek?

SB: Yes.

And on the flip side, do similarities also hold your interest? I’m thinking, for example, of A Small World. [In collaboration with Jennifer Zackin, A Small World included two parallel projections of the artists’ home movies projected in a space with shag carpeting and wood-paneled walls. Despite any assumed contrast of growing up as the artists did on the East and West Coasts, respectively, and the differences between Jewish and African American families, the juxtaposition seemed to emphasize overlap, or similarity rather than difference.]

SB: I think a lot of syncretism, as you mentioned earlier. I think of archetypes, of things that are used by every culture in some form because they serve us as humans.

Difference becomes another tone, another way of destabilizing predictability in the work. I think a lot of obstructions and challenges when I’m in the studio. By now I could have made some very uniform procedural choices in terms of making huge bodies of work that look similar, but I’m not so interested in that.

I’m actually interested more in tone: when a piece feels provocative rather than subtle and comforting, another brash and abrasive, or one might feel slick, or jagged. The best analogy I could use is if you think of a musician or a writer...you don’t want them writing the same book for ten years straight, and an album has to have some catharsis, some dips and dives. I like to think of my body of work doing the same thing. When it comes to making pieces, even within a series, I like having different tones.

And when you said “obstructions,” what did you mean?

SB: Like I won’t use this color in this piece, or I’ll limit my palette, materials, or scale in another, or I’m only going to use scissors for a different one. Prompts. Things to get the juices flowing.

While obviously not exclusive to women, quilting is considered “of women’s hands.” Was that significant for you as a starting place or an added layer? Also you’ve called yourself a “quilt listener”; will this carry on, going forward?

SB: To the gender question: I do think it was there in the beginning. As much as I would like for gender to not be an issue with the work, I’m a man using these things that presumably were made by women. What helps me reconcile that is that most of the quilts I’m working with were in the dust bin. They were going to go, so there would be no conversation. There would be nothing to say, no history, no relic. Part of the process is giving them a second, third, or fourth life, just like every scrap that’s on them. I had to think about it in a larger patchwork mentality. I often compare it to sampling; it is resurrecting an older piece of work. That’s why I often talk about transformation. I think for me to use these older works, I have to put a little skin in the game. That’s the actual handwork, the handling, the deference and reverence I pay to them. They’re power objects. I’m adding layers, and putting it back out there, hopefully to be read somewhere in the future, complicating notions of gender, time, meaning, and the way we read these pieces.

Do you think you’ll continue?

SB: Oh yeah, I thought I was going to stop this years ago, but I keep getting excited about them. There’s so much more I want to try. I play a lot in making them, which is back to one of your earlier questions. It’s meditative, a very personal and expressive way of working.

In a strange way, I feel like I show a lot of vulnerability in those pieces. My life was led and taught by multiple extremely strong women. It’s natural for me to feel like I’m sitting at the quilting table, you know what I mean? Listening. Like “boy go get that piece of thing” and “go get this” and, I’d be right there, just sitting by my mom and her friends while they’re doing their thing.

Were they quilters?

SB: No, my mom used to read all the fashion magazines and find the couture stuff that we couldn’t afford. She would go the garment district with me in tow and find all the fabrics that she liked. She’d take the patterns or even the pictures to various women in our neighborhood. There was a German woman who was an incredible seamstress. There was a black woman who had a boutique. There was a Chinese woman who had incredible jewelry. All of this was in the Leimert Park and Baldwin Hills areas of L.A.

I would go to those homes, boutiques, and garment stores and go through every step with my mom because I was the youngest. I heard the women talk. I didn’t even make the connection to my own personal history until probably five years into this, into the quilt series. And I thought, oh my God, this is all about Mom. I was a fly on the wall and I learned from those experiences.