Hunting the Lonely Heart

What made Carson McCullers so different from everyone else in her sad and faraway hometown of Columbus, Georgia?

By Elizabeth McCracken

"Carson McCullers," 1940, silver gelatin print, by Louise Dahl-Wolfe. Courtesy The Columbus Museum, Georgia; The Edward Swift Shorter Bequest Fund © Center for Creative Photography, Arizona Board of Regents

Editor’s note: This essay was originally published in October/November 1996 (Issue 14). “Wrong-Headed and Irresistable,” a companion to this essay, appears here.

The books I love best I remember two ways: what happened in the world of the book, and what I was doing myself at the time: where I sat, what my daily habits were then. In 1988, when I first read The Heart Is a Lonely Hunter, I was twenty-two and in graduate school, in the first apartment of my adult life. I’d just begun to believe that I could be a writer, so I read differently, trying to figure out how the author did it. Clearly, any writer had strengths and weaknesses: if only I paid diligent attention, I could see them, and then divine the gears behind the story.

It took me three or four sentences in The Heart Is a Lonely Hunter to give up on that theory. That is, I saw, just as I’d planned, what Carson McCullers was good at: She was going to break my heart again and again. I sat in the orange armchair that had come with my apartment; I clutched my paperback, with its pulpy gray pages and ugly cover illustration. Reading, I could not see any gears at all, because the characters—these actual, living people she wrote about—obscured them. I could no more see how she did it than I could fall in love with someone and see how that person absorbed vitamin D from the sun.

Partway through the book, I had an experience I’d never had before, and have never had since. At one point, twelve-year-old Mick Kelly and her younger brother Bubber are sitting outside when Baby Wilson, a four-year-old girl whose mother is grooming her for Hollywood, walks by, dressed in pink, swinging a pink pocketbook. Bubber loves Baby, and pleads with her to let him touch her pretty outfit. He is shouldering a borrowed rifle. Baby walks on and Bubber aims his gun at her and you know he doesn’t mean to shoot her but—

I sat up in my chair. At the bottom of the right hand page, Bubber was aiming the gun at Baby. I knew what was going to happen on the other side, but the scene and characters were so real to me I somehow believed if I didn’t turn the page I could prevent it. I could save Bubber and Baby and Mick. I desperately wanted to do it.

Eventually, of course, I turned the page, and everything happened.

That’s one of the miracles of Carson McCullers: she writes characters you want to save. They are naive and blind in love; they are passionate about lost causes; they make mistake after mistake, but somehow you love them so much you want to rescue them. There are many moments in The Heart Is a Lonely Hunter that still make me gasp with worry and regret for the characters: I don’t want life to treat them so badly, because they deserve so much.

McCullers’s characters are at the mercy of their own bad decisions, it’s true, but also at the mercy of the Southern towns they live in, places that resemble her own hometown of Columbus, Georgia. The town in The Ballad of the Sad Café is described as “lonesome, sad, and like a place that is far off and estranged from all other places in the world.” Frankie Addams, the heroine of The Member of the Wedding, wanders through her town constantly and she says, at one point, “I just wish I could tear this whole town down!”

There’s no telling whether Carson McCullers herself wanted to tear down Columbus, a fairly large mill town in the middle of the deep South. These are the facts of her Columbus life: Lula Carson Smith was born here February 19, 1917, the first child of Lamar and Marguerite Smith. Her father was a watch repairman, her mother a smart and ambitious woman. Lula Carson was always the favored child, even after her younger brother and sister were born. By all accounts, her mother expected her to be a genius from the start. She grew up different from other children, but there’s no explaining why, exactly: maybe she was odd enough to be excluded by other children, or maybe she was accepted but so disdainful that she became excluded. Maybe she was too spoiled by her mother. Maybe she was gay or bisexual, and this difference shaped her life. Maybe she was a genius, and this shaped her life. Maybe she wasn’t pretty enough (being jowly even as a child and extremely tall). Maybe she was just too busy assessing the daily life of Columbus, standing aside and thinking, to ever join in. In every town on any day, there are spoiled girls, and not-quite-pretty-enough girls, and girls struggling with their sexuality, and odd girls. Maybe she was born with a certain combination of attributes that meant she was to do things all her life: watch and judge and long and write it down.

Nevertheless, she was from a nice family. She went to public school. Interested in music, she studied piano and was either extremely talented or a prodigy. She studied with Mary Tucker, wife of a lieutenant colonel stationed at Fort Benning, who became one of the important grown-ups of her life. Mrs. Tucker introduced her to Edwin Peacock, a young man who gave Carson things to read, including Story magazine. She gave up music to write. She left Columbus for New York City. Later, she would do a million things: return to Columbus sometimes; meet Reeves McCullers, marry Reeves McCullers, divorce him, and then marry him again; write several original, creepy, immortal pieces of fiction (and several things that would not quite fulfill all of those categories); meet famous people; suffer stroke after stroke, the first at twenty-four and then a more serious one at thirty and then even more; die at fifty in Nyack, New York.

But Columbus haunted her. In The Heart Is a Lonely Hunter, Mick Kelly thinks about her girlhood crush on a schoolmate named Celeste, who holds her stuffed egg in her hand and puts her thumb down into the yolk without even thinking about it. Columbus’ thumb print is all over Lula.

So when I went to Columbus, Georgia, looking for Carson McCullers, I had some idea of what to expect. First of all, it would be hot, since it was August, and it’s usually August in Carson McCullers’s world: it’s all you can do to move through your daydreams, never mind the actual wavering world. Also, I would be alone. I imagined myself trudging through the heat and peering into the shop windows.

McCullers’s characters are at the mercy of their own bad decisions, it’s true, but also at the mercy of the Southern towns they live in, places that resemble her own hometown of Columbus, Georgia.

***

Coumbus is not these days merely “the home of Fort Benning and an infinite number of strip joints, tattoo parlors, and high-end shopping opportunities like Wild Bill’s Park-N’-Pawn,” as David Remnick describes it in an August issue of The New Yorker. While it’s true that Victory Drive, which leads from Fort Benning into town, has everything a bored but unadventurous soldier might want, it is only one road. The city itself has a little of everything. It is home to five Fortune 500 companies, and a number of beautifully converted mill buildings; an historic section with restored Victorians and various architectural oddities, including a log cabin; antebellum houses; shotgun shacks in such disrepair that you can’t imagine how anyone could live in such a tiny, dismal space; identical but rehabbed shotgun shacks that look charming and compact. The downtown has been retrofitted, too, though not as deliberately or elegantly as the mill buildings along the Chattahoochee River. Like downtowns of cities in every part of the country, there is no longer anything busy or important about it. Flat, painted signs for “New York Fashions” and beauty supply shops hover on storefronts meant for grander businesses. Kresse’s department store—Mick Kelly has a dream that is more crowded than “Kresse’s store on Saturday afternoon”—has burned down, leaving only the front wall intact, blue sky in its attic windows. The Springer Opera House, built in 1871, is still standing, a handsome brick building that hosted performances by Oscar Wilde, Mr. and Mrs. Tom Thumb, Edwin Booth, and John L. Sullivan. Columbus is the hometown of Gertrude “Ma” Rainey; Dr. Pemberton, the inventor of Coca-Cola; Nunnally Johnson, who wrote or co-wrote the screenplays of (among others) The Dirty Dozen, The Three Faces of Eve (which he also directed), and The Grapes of Wrath; and Lula Carson Smith McCullers.

***

Carson McCullers is not much in evidence, officially, in Columbus. Her family house on Starke Avenue has an historical marker (similar markers flag the houses of Ma Rainey and Dr. Pemberton). The public library has two cases with first editions. Both the display case and the marker are thanks to The Friends of Carson McCullers. A tiny McCullers exhibit is temporarily up at the Columbus Museum. The week I was there a local theater group was staging The Lonely Hunting, a collection of scenes from her work. That’s it.

Unofficially, though, McCullers is still here. It is wrong-headed and irresistible to try to look at a writer’s real life and wonder what in it directly corresponds to the author’s fiction; it’s like marrying a man because he reminds you of your beloved first husband. I know this. Even so, I am ready to do it, ready to listen to stories and stare at the buildings for the four days I’m in Columbus. And to stay in the Carson McCullers mood, which is essentially this: hot, hopeful, misunderstood, and lonely.

The weather did not cooperate—it was lovely and moderate—and neither did the people. They were much too friendly, much too helpful, and frankly they would not leave me alone to sulk for a single minute. For instance, before F. Clason Kyle met me at the airport, all I knew was that he was some guy who knew something about something—maybe Columbus, maybe Carson McCullers—and that he had a car.

Clason Kyle turned out to be about the nicest man in the world, a local historian and writer, author of Images: A Pictorial History of Columbus, Georgia. He didn’t tell me that right away, he just took me to lunch at a restaurant that featured a club sandwich named “the Kyle” and claimed it was for him. “I am a local institution,” he said modestly, ordering a different sandwich off the menu. I thought he was joking.

He wasn’t. Anywhere I went with Clason—and he graciously showed me much of Columbus—we met at least a dozen people who knew him. Among other things, he’s a former staffer at the Columbus Ledger-Enquirer (police reporter, travel writer, music and drama critic, and columnist); an original and current trustee of the board of The Springer Opera House; an enthusiastic owner and renovator of historic houses. I admit, though, that the item in Clason’s resume that excited me most is that he was Columbus’ liaison to John Wayne during local filming of The Green Berets. (He even has John Wayne’s signature on a closet wall in his guest house, at an appropriately John Wayne height, prefaced by these words of wisdom: Smile, you’re on Candid Camera. The Duke had lovely handwriting. There is also a picture of Arthur Fielder learning to do the twist, and two guest beds, one with a plaque that says, Edward Albee slept here, one that makes the same claim for Truman Capote.)

***

I’m staying at Miss Weese’s Victorian Bed and Breakfast, owned and operated by Miss Weese herself, Louise Tennent Smith. Miss Weese is not a native Columbusite— she’s from Atlanta originally, and came to Columbus after living in Miami for many years. “I wanted to come back to Georgia,” she tells me, “where the rivers are the right color and nobody has an accent.”

My first night, Clason takes Miss Weese and me to dinner; for this Northern girl, it was like watching an exhibition of Southerners in their natural habitat. They gossiped about friends and then complimented their friends’ good nature; they complimented and teased each other. They try to explain to me the difference be-tween the natives of different Southern towns: it seems to hinge on how they’d say, “Hey! How you? Love your hair. How’s your mama?”

At the end of the evening, when Miss Weese and I leave Clason on the sidewalk outside his house, she rolls down her window and says, “Good night, Precious Thing.”

Clason is doing a solemn Egyptian-inspired dance as a farewell.

This doesn’t seem like the right way to start research on an article about Carson McCullers. I mean, clearly I am having too much fun.

***

The Carson McCullers I find in Columbus appears in stories and gossip; I’m not sure what will happen when her generation dies. Clason introduces me to Norman Rothschild, a school friend of McCullers from kindergarten. “Someone once told me that I was the greatest name dropper since Genesis,” Norman tells me, and here are a few of the names he drops: Edward Albee, Tennessee Williams, Truman Capote, Anaïs Nin, Christopher Isherwood, Elizabeth Bowen, Paulette Goddard (with whom he appears in a picture in his kitchen), Gore Vidal, and all the members of Beyond the Fringe. And Carson McCullers, whom he seems a little less impressed by, since she was merely a neighbor in Columbus.

When I ask how Columbus reacted upon publication of The Heart Is a Lonely Hunter, he says, “Everybody thought it was good that a local had published a book. But Nunnally Johnson had written novels, and movies. People just didn’t talk about it. Just one more thing happened in Columbus.”

They remained friends after she left town, though he says she was a difficult person. Once, when Norman visited her in France, he told her that he’d just had dinner with Gore Vidal.

“She said, ‘Don’t you ever mention that name again in my house.’ That’s the way she was. She pointed at a bookcase filled with translations of her work, and said, ‘I’m proud of this, aren’t you proud of me?’ I said, ‘Of course I am, Carson, I love ya.’

“Her best line,” he tells me, “was always, ‘Norman dear, are you happy, are you ha-a-appy? Well, what the shit’s happy?’” He laughs. “I don’t know. I’ll be eighty next month. I’m about a year or two older than Carson, and I never let anything worry me, but Carson worried about ev-erything. She was her own worst enemy.”

***

Margaret Sullivan, the founder of The Friends of Carson McCullers, remembers the first time she heard of Carson McCullers. In 1951—at the end of the decade during which The Heart Is a Lonely Hunter, The Ballad of the Sad Café, and The Member of the Wedding were all published—Ms. Sullivan was a senior in high school and heard about a Broadway play (McCulIers’s own adaptation of The Member of the Wedding) written by a Columbusite. So she asked her homeroom teacher about the author.

“Miss Lawrence pursed her lips, drew herself up with a deep breath, and replied, ‘We don’t talk about her. She’s perverted!’”

When Sullivan got home, she looked up ‘perverted’ in the dictionary and found that it said, “turned out of one’s natural course.”

“Well, frankly,” Dr. Sullivan says, “that didn’t seem such a bad thing to me. In fact, I thought, wasn’t that what education was all about anyway? To rescue us from our natural inclinations and to steer us in the ways of the best that had been thought and discovered and created over the long course of civilization?”

After that, Margaret Sullivan went on to think a lot about McCullers, writing both her master’s and doctoral dissertations on her. She got to know some of her friends, including McCullers’s analyst, Mary Mercer, and Edwin Peacock, her childhood mentor. She interviewed McCullers herself, at the end of her life, far away from their hometown. McCullers, then an invalid, was living in Nyack, New York.

Clearly, it tickles Dr. Sullivan that someone is thinking of writing about Carson McCullers. She lends me her doctoral dissertation, and shows me stacks of early photographs, some given to her by Edwin Peacock. You can always pick out Carson, she points out: “Just go through and find the kid looking gloomy.”

“Columbus didn’t treat her kindly,” says Ms. Sullivan. “It never has. Somebody said when she wrote Reflections in a Golden Eye, ‘The town went straight up.’”

I tell Dr. Sullivan about a friend of mine who’s writing a novel about a thirteen-year-old girl, and is reading McCullers for help.

“Is it a literary problem or a personal problem?” she asks. “Because either one, I think people tend to look to Carson for help. You’ve probably felt it, too, reading her: your whole life opening up.”

Later, the two of us drive to Fort Benning—beautiful and green—where Mary Tucker lived and Carson took piano lessons. Reflections in a Golden Eye, McCullers’s wonderfully perverse—in all senses of the word—second novel is set at Fort Benning, and it’s easy to imagine the particulars of the novel sneaking through the lush night. We drive down Victory Drive, with its one-stop sinning—tattoo shops, pawn shops, and “lingerie modeling” at one intersection. “The New Yorker should have seen it when,” Margaret Sullivan says. Back in Columbus, we drive up to Edwin Peacock’s garage apartment, where Peacock, Carson, and Reeves McCullers had drinking parties; now there is a human skeleton set up in the window. “Isn’t that cute,” Dr. Sullivan says. Yes, I guess, and certainly all I deserve for peeking in windows.

The same day I meet Margaret Sullivan, I chase down Carson McCullers in a car driven by Thornton Jordan, an English professor retired from Columbus State University, who offers a twice-yearly slide show on McCullers’s Columbus. I admit I get a strange thrill when he says things like, “That’s the library, where Singer checked out a mystery novel every week.” Singer is a made-up character from The Heart Is a Lonely Hunter, but there’s the library, real as dirt. And there is the site of Alex Mitchell’s fruit stand, model for Charles Parker’s fruit and candy shop in The Heart Is a Lonely Hunter. Here are the neighborhoods that Frankie Addams, the heroine ofThe Member of the Wedding, walked through on what she imagined was her last day in her old hometown. There’s the cast-iron bank that Antonapoulos urinated on (though McCullers moved it a block closer to the fruit stand); there’s the house of Sidney Spain, a neighbor who died young and possibly inspired the death of John Henry in The Member of the Wedding. Carson’s own father repaired watches, as did Mick Kelly’s and Frankie Addams’s; and John Singer, the deaf-mute center of The Heart Is a Lonely Hunter, worked as a silver engraver. We note the shops where Lamar Smith, and perhaps some of his daughter’s creations, worked.

Each one of these sites sits quiet and unmarked, and if it weren’t for Thornton Jordan I wouldn’t know what they meant. I can picture her characters walking through the town; it delights me that I now know what windows they stared through. Broadway is a long boulevard one block away from the river, plenty of room for a young girl to wander. On this ride, Carson McCullers comes clearer to me as a person than at any other moment during my visit to Columbus. Still, she’s only clear from a distance, an over-tall girl with uncombed hair, dressed in men’s clothes, slipping through doorways, haunting Broadway, visiting her father.

***

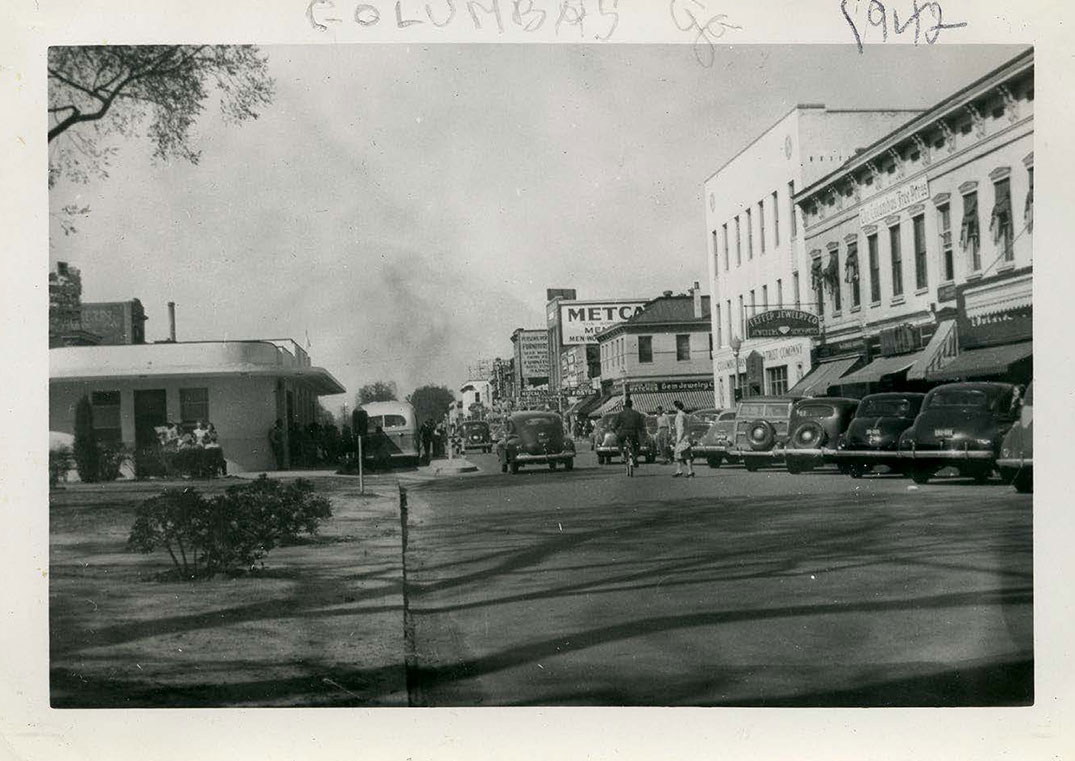

Photograph of Columbus, Georgia, 1942, silver gelatin print on Velox. Courtesy The Columbus Museum, Georgia; Gift of Janet Kelly Morgan

***

It’s hard to fill in the gaps between the stories I hear in Columbus, though I hear delightful ones. Norman Rothschild tells me that his friend Anaïs Nin told him, “Carson writes well, but I have no use for ugly women.” Daisy Tucker, who used to work at the newspaper, says that the paper’s editor called Carson “the first hippie I ever saw.” Clason Kyle remembers meeting her only once, at a tea party attended also by General Patton, who used the term “son-of-a-bitch” to Clason’s aunt (she dropped her teacup) and later shot his pearl-handled revolvers from the front porch. Clason met Carson in the pantry; she was dressed up in a tartan skirt, knee socks, possibly a tam-o’-shanter, and definitely brogans, while all the other women wore long gowns. “I should have pursued her,” he says, “but I didn’t.” Billy Winn, the sad-eyed editorial page editor at the Columbus Ledger-Enquirer, says that his mother was scandalized because she heard that when Carson fell off a horse at Fort Benning, she turned up braless. Says Winn, “Anytime someone would bring up Carson McCullers, Mother, first of all, wouldn’t know who that was, you’d have to say you were talking about Lula. Oh that girl, she would say, ‘Well,’ she would say, ‘She didn’t wear a brassiere.’ That was the end of her.”

I hear fond gossip, and unfond gossip, and even some vaguely lurid stories about the intensity of her crushes—but it doesn’t quite add up to a person. Her own work is about the spaces in between gossip, how people’s internal goings-on explain their scandalous behavior. There’s plenty of action in her novels—shootings, a twelve-year-old girl going off with a soldier and then attacking him in his motel room, lawsuits, fistfights, weddings, deaths, and misguided sex. Still, none of that action is what her work is really about. In The Ballad of the Sad Café, you can feel the force of gossip all around: Miss Amelia, one of the main characters, a six-foot tall, cross-eyed bootlegger, exists in two ways: the original version, and a six-foot, cross-eyed shadow composed of town rumors.

Perhaps this is true of anyone, and constructing a person out of stories is foolish: it is, after all, what happens to John Singer, the center of The Heart Is a Lonely Hunter. People talk about him constantly, and come to their own conclusions:

The Jews said he was a Jew. The merchants along the main street claimed he had received a large legacy and was a very rich man. It was whispered in one browbeaten textile union that the mute was an organizer for the C.I.O. A lone Turk who had roamed into the town years ago and who languished with his family behind the little store where they sold linens claimed passionately to his wife that the mute was Turkish. . . .

The rich thought that he was rich and the poor considered him a poor man like themselves. And as there was no way to disprove these rumors, they grew marvelous and very real. Each man described the mute as he wished him to be.

I have always loved Carson McCullers, but over my few days in Columbus I fall in love with her, no doubt because she’s further away than ever.

***

Though I talked to lovely people who remembered her, who think about her, who have even studied her—Carson McCullers isn’t here. Billy Winn puts it this way: “She’s a ghost. I think of her as a ghost.” I’ve heard about men like Billy Winn before—newspaper men who are, deep down, poets. I’ve come to his office to get some background on Columbus; it’s the same building where McCullers herself worked one summer, briefly, a dreamy girl in a beret. Billy Winn tells me he’s not sure why I’ve come to him, considering that his paper (in a review of the playThe Lonely Hunting) had misspelled her name a dozen times the day before.

With enormous regret, Billy Winn tells me that he doesn’t think too many people know who Carson is anymore. “It’s very spooky. She’s a non-person. Unless you meet someone who knew her as a young girl or later, or if you talk to an English teacher. But most people know very little about her. I can’t account for it, except to tell you that it’s so.”

He gives me some local history. “Columbus is an extraordinarily isolated place. I don’t know if you remember that line—‘a sad, faraway place’—from The Ballad of the Sad Café. That’s sort of, I think, how she viewed Columbus, and I think that’s a fairly accurate picture of it, especially when she was a girl growing up. We weren’t even on the interstate highway system here till, I think it was, 1978. So it was tremendously isolated, geographically, psychically, psychologically, socially, any way you want to talk about it.”

He seems frustrated and pessimistic about the absence of McCullers in town. “I grew up in a house in which the operating mystique was rooted in about 1840. Seriously. And I think that people who grew up after me, you know, made it finally to the 1940s or something. But it’s like Columbus is a city poised to leap into the 1960s. Maybe they don’t like Carson because she’s modern in some way that they don’t approve of.”

As I leave, he says, “One more thing about Columbus. I don’t know if this is any help to you or not, but there’s a certain hollowness here of soul. There’s not enough stuff at the center. In a sense, she was a displaced person in this society.”

***

It’s enough to make me feel guilty for rather enjoying Columbus, as though I’ve met the parents of a friend who I know had an unhappy childhood, only to tell her, “Actually, I thought they seemed rather nice.”

Real parents, especially mothers, play a small role in McCullers’s novels; they are mostly absent, and servants or strangers do the mothering. It’s the towns themselves that hover and judge and offer nutrition, in the form of cafés, and entertainment, in the form of under-construction houses.

These towns are bad parents, and Columbus itself was puzzled by its daughter, whether it was going straight up after Reflections in a Golden Eye, or was merely worried, as Sullivan says it was, after The Heart Is a Lonely Hunter. Latimer Watson, in the Columbus Enquirer in 1942, wrote, “Columbus, even if it doesn’t always understand her, is proud of Carson and would like to know her better.”

Wouldn’t it kill you to hear your mama say that?

McCullers is a tragic figure. She led a short life—she died in 1967, making next year the eightieth anniversary of her birth and the thirtieth of her death—but even so she apparently outlived the depth of her gifts. She was always ill, but particularly after her thirtieth birthday.

She wrote all her great work in her twenties. Almost nobody has heard of Clock Without Hands, her last novel, or The Square Root of Wonderful, her second play, and it’s probably a good thing: they’re not so awfully bad, but they are nowhere near the better-known stuff.

Columbus is not a tragic place, as far as I can tell—it charms me, though it’s no doubt as impossible to understand a town by looking at its neighborhoods for several days as it is to understand a writer by looking at her hometown.

***

McCullers wrote about gossip, and lonely towns in the South, but mostly she wrote about unrequited love. In The Heart Is a Lonely Hunter, four characters fall in love, in their own ways, with John Singer, a deaf-mute, who himself loves the dreamy, slow Antonapoulos, who, in turn, loves food and drink and “a certain solitary pleasure.” Berenice, in The Member of the Wedding, says that she’s never before heard of someone who, like Frankie, is in love with a whole wedding. (We can assume that Frankie’s brother and his bride are in love with each other, but they are never onstage.) In The Ballad of the Sad Café, Marvin Macy loves Miss Amelia, who loves Cousin Lymon, who loves Marvin Macy.

She writes, in Ballad:

First of all, love is a joint experience between two persons—but the fact that it is a joint experience does not mean that it is a similar experience to the two people involved. There are the lover and the beloved, but these two come from different countries. . . .

It is for this reason that most of us would rather love than be loved. Almost everyone wants to be the lover. And the curt truth is that, in a deep secret way, the state of being beloved is intolerable to many. The beloved fears and hates the lover, and with the best of reasons. For the lover is forever trying to strip bare his beloved. The lover craves any possible relation with the beloved, even if this experience can cause him only pain.

Everywhere in McCullers’s work, there are lovers gazing upon their beloveds, wondering and hopeful and desperate and disappointed and still, somehow, hopeful. And the reason her work means so much is that nobody, not one of us, is any better, or any worse.

Not me, that’s for sure. I have always loved Carson McCullers, but over my few days in Columbus I fall in love with her, no doubt because she’s further away than ever. Even the biographies I read don’t bring her any closer. I begin to believe that if only I had a chance to talk to her—the yellow-haired scatterbrain from a local newspaperman’s memoirs, the over-tall sloppy girl on the streets of Columbus, the prodigy, the stroke-ridden invalid—surely, at any time, if we’d met we’d become good friends. Like Clason, I would’ve gone into that pantry, but I would stay: we’d discuss Ulysses. I’d tell her she was better than that old Nunnally Johnson, that terrible Gore Vidal. We would’ve understood each other.

I don’t quite meet her in Columbus; I stalk her, looking with fascination at places she’s been. When Clason shows me the splendid interior of The Springer Opera House and says, “I’m sure Carson was here at some point during her childhood,” I think, Really, and look at the seats with added interest, wondering whether I could by some trick find her seat and sit in it, and conjure her a little closer. This doesn’t seem healthy. I can see her walking like one of her characters down Broadway, past the bank, into the black neighborhoods and back again; I can imagine her stopping and staring into Alex Mitchell’s fruit stand. I can myself stand outside the Columbus Ledger-Enquirer building and look up (my back to the river, because I have been told her office faced it) and imagine her looking dreamily out.

I can believe this all I want, but nothing I do will make Carson—always at a distance in my picturing of her, her thoughts on something else—lift her gaze to look at me.

I could never be a biographer: any biographer is an unrequited lover. In fiction, you can make your characters love you; at least, you can believe that they would love you, because God, you love them. An actual person is more difficult. Of course none of this does any good; love is futile, inevitable, improving, the worst of fates, the best. It will give you hope, then kill you. Any Carson McCullers’s character can tell you that.