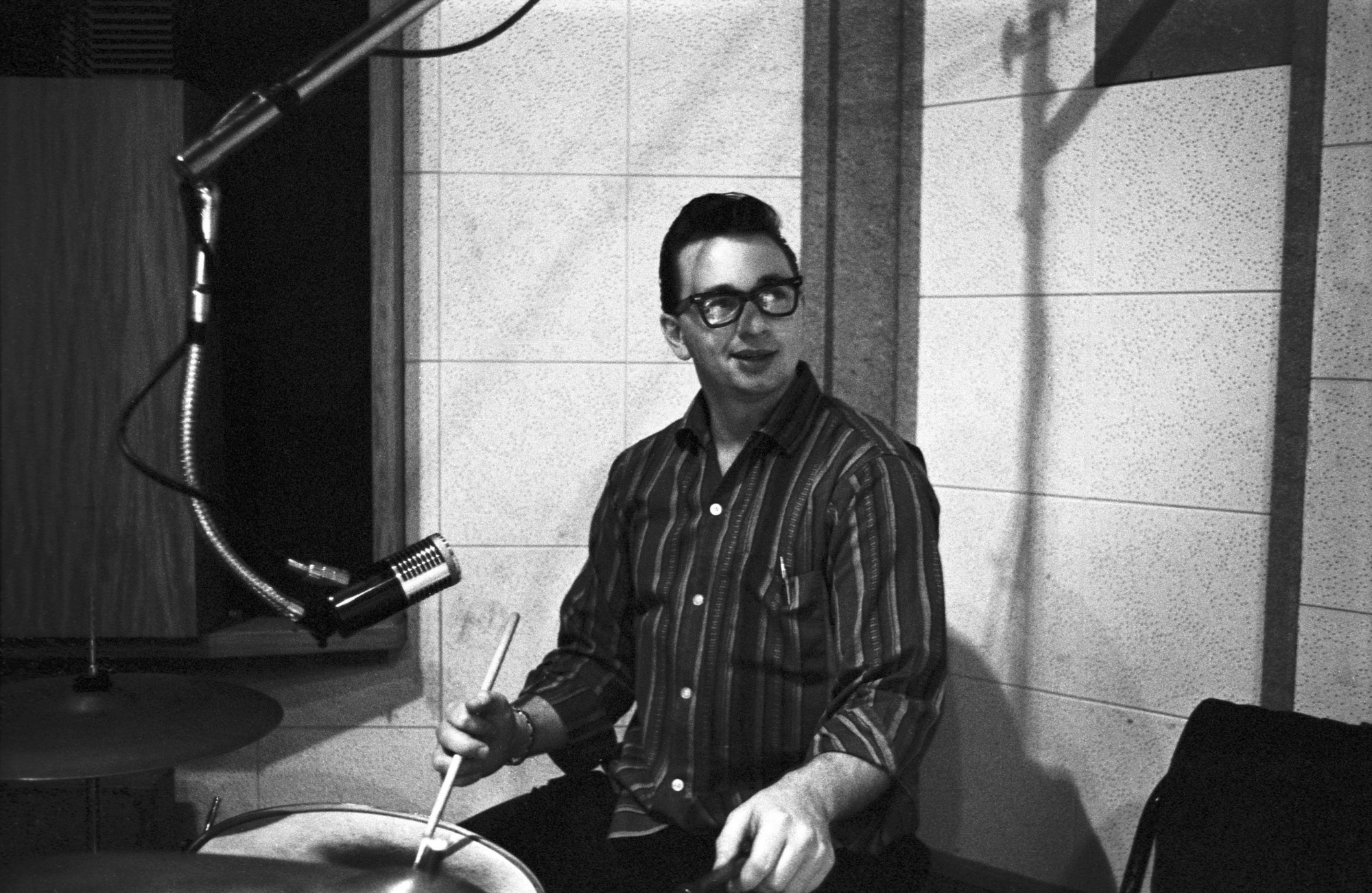

Photograph by Sid O’Berry. Courtesy the Grand Ole Opry Archives

Silent Heartbeat

Buddy Harman and the quiet revolution of country drumming

By John Lingan

When Delta families gathered on humid Sundays in white-painted, wood-floor churches to sing the gospel by ear and rest their weary planters’ bodies, they didn’t bring percussion. When cowboys in mud-flecked boots built fires in the shadow of the Rockies and shared high-lonesome musical lore, they carried guitars and harmonicas, not sticks and mallets. Among the Appalachian Scots-Irish, one cardinal instrument—the banjo—belied an African origin, but its drum was purely a resonator; mountain music was strings or vocals only. And even though rhythm was central to breakdowns and fleet soloing, the instrumental thinness was purposeful. Back to its earliest forms, before a genre called “country” had even emerged from the primordial ooze, it was keening and skeletal, not beat-driven.

Country musicians’ skepticism, even antagonism, to drums persisted well into the twentieth century. But today, country and rock have been so thoroughly absorbed and reflected into each other that it’s impossible to tell which is a subgenre of the other, and drums are now as fundamental as electric guitar or pedal steel. Before World War II, this was music for barn dances, and by the mid-Sixties, it was built for expensive hi-fis and rock clubs. For such an inherently conservative tradition, that’s a veritable revolution.

It happened in a relatively few years, and not noisily. Drums snuck into country music. None of its parent genres—gospel, western, or hillbilly—relied on percussion beyond maybe a church tambourine. But when those varied roots entwined in Nashville around the late Thirties, they became the playthings of record producers with hit-making on their minds. And for this new omni-genre to leap and snap like “pop,” it needed drums. That’s what distinguished the reigning swing bands of the day and, within a few years, the hottest Southern-inflected r&b groups and Chicago electric guitarists. Whether in jazz, gospel, or country blues, drums were the addition that made regional folkways into cultural phenomena. The bigger the beat, the more easily adopted by a national audience in the U.S. But the delicate components of country music at that time, including close harmonies and acoustic instrumentation, ensured that drums would only play a supporting role. Even in this new commercial country, there could be no equivalent to Benny Goodman’s 1937 “Sing, Sing, Sing,” in which Gene Krupa invented the drum-showcase chart hit, even though a decade earlier Krupa had recorded a few sides accompanying blackface yodeler Emmett Miller.

Instead, drums were used as texture, first just a snare played lightly with brushes. Take an archetypal 1950s waltzing crawler, Jim Reeves’s “He’ll Have to Go.” It’s the kind of airy, romantic Nashville cheese that Reeves reveled in and humbly diminished as “lazy man’s music.” You might have to lean forward to catch the metronomic, cotton-soft snare pattern keeping time beneath the piano, guitar, vibraphone, and backing vocals. But without it, this pillowy arrangement would float away. That unstraying drum part gives a basic shape and speed to an overly prettified, quite simple ballad. It adds a steady heartbeat to a recording that’s otherwise all smooth edges.

It’s such a simple performance, you might not think the session required a drummer per se—any studio hand with good rhythm could do. But that snare credit belonged to Buddy Harman. And “He’ll Have to Go” isn’t even high on the list of Harman’s most ubiquitous or successful sessions, just as Jim Reeves barely rates among the veritable deities that Harman recorded for and with.

Before “He’ll Have to Go,” which went to number two pop and number one country, Harman had already drummed on a handful of epochal rock & roll records, including some by the Everly Brothers and Elvis, though he was just embarking on a country-industry career that would soon match any Nashville Cat’s. Along with a small brotherhood of fellow Music Row percussionists, he reared country drumming from its infancy into adulthood. No one recorded or did more on the instrument than Buddy Harman during the time when the instrument became crucial. He never played a solo or sang a chorus, but Harman was one of the genre’s transformational figures.

Unbelievably, his mother played drums, a rarity now and a near-scandal for 1928, when Buddy was born in Nashville. His youngest memories include a house littered with percussion instruments thanks to his parents’ husband-and-wife music duo. But his own interest didn’t arise until after the band ended and Mrs. Harman had sold it all.

He was the perfect early adolescent age when “Sing, Sing, Sing” mania arrived. Buddy worked as a movie theater usher to afford a set of white-pearl Slingerland Radio Kings, Krupa’s kit, which he bought for seventy-five dollars and paid off in three-dollar monthly installments. He listened to Benny Goodman and Buddy Rich on 78s to hear his new heroes, he took private lessons, played in the school band and the marching band. As often as he could, he went to gigs in town just to watch other drummers and steal tricks. The instrument consumed him. He joined the Navy at eighteen just so he could get G.I. Bill funding for music school. It was 1946, a merciful time to enlist, and by 1949 he was enrolled at Chicago’s Roy Knapp School of Percussion.

At that point Buddy’s taste and career prospects rested on dance bands—swing bands. The best-known name in country drumming then was Smokey Dacus, late of Bob Wills’s Texas Playboys, and Dacus, too, had come out of the pop-jazz world. But instead of a life on the bus and the bandstand, Harman was blessed to return home and find local touring and recording work with singer Carl Smith, an eventual member of the Country Music Hall of Fame who was one of the first Nashville stars to bring drums into his band. That attracted the attention of Chet Atkins and Owen Bradley, dual architects of the ascendant Nashville Sound, who put the vibraphones and lounge piano in honky-tonk songs.

Atkins was an instrumental and technical savant, a pioneering electric guitarist with flawless technique who also established multitracking as a standard recording practice. Bradley, for his part, was a protégé to legendary broadcaster and producer Paul Cohen and a onetime employee at Cohen’s Castle Recording Studios, the first commercial venture of its kind in Music City. Bradley was also an executive for Decca Records’ Nashville division.

In other words, these were men of resources and their creative ambitions reflected that. The defining element of Nashville Sound country is that it feels expensive: the strings, the gauzy choral groups, the depth and richness, the dependable brilliance of every musician involved. It’s a luxury brand item. That’s not reflective of country’s roots, of course, but Nashville Sound producers were unique for not worrying if a few of those roots were lost altogether. It wasn’t like Bradley or Atkins lacked respect for tradition, they were just young creative minds with access to a postwar deluge of new technology and new money. And for all its success, the Nashville Sound was controversial for certain stakeholders in a subculture that fetishizes purity. There have always been people who think country should only have fiddles, not violins. But Nashville is where a sweaty mess of regional influences became known as “country music,” sellable item, in the first place, and Atkins and Bradley were the engineers who designed the factory.

When they first called in Buddy, he had already played on “Bye Bye Love” and “Rockin’ Around the Christmas Tree,” bouncy pop tunes with a pronounced swing. Atkins produced “He’ll Have to Go” and other Jim Reeves masterpieces. But in 1960, Decca signed a young Virginia native named Patsy Cline, and Owen Bradley was suddenly gifted a voice worthy of his broadest talents. Patsy’s Decca sessions with Bradley include many of her enduring and popular tracks, including “Always,” “I Fall to Pieces,” and “Sweet Dreams,” and Harman played on all of them.

Remember that there was no template for drumming on country records by this point, especially not in a studio like the one that Bradley infamously built in a customized Quonset hut, with state-of-the-art mics and precision track separation to ensure perfect clarity and detail on every instrument. Harman was used to really pounding his drums on those rock & roll sessions with Elvis, but these twangy ones required the opposite: He had to play like his kit was made of lace. Sometimes, he remembered later, he made the kit disappear and simply impersonated it: “Instead of playing drums, they had a mike in front of my face. I was going chhh, chhh, chhh.” More often, he’d add a hint of backbeat with a little rim-click on top of his snare brushing, as on Patsy’s “She’s Got You.”

With Patsy Cline, Buddy Harman had such a freakishly, multifacetedly talented client that he got to play everything for her: light shuffles, torch songs, bluesy rave-ups, orchestral pop, hardcore country, and a few dozen future American standards and karaoke stand-bys. And she appreciated him: Harman told a twenty-first-century interviewer that Patsy liked a lot of drums, perhaps because of her own early affinity for swing groups and Elvis. The music he recorded with her, especially the tear-stained songs that defined her legacy after she died in a 1963 plane crash at age thirty, is cherished Americana, remarkable for its mystique and control. She elevated her material like no one else in the genre or elsewhere, and Bradley’s arrangements were wide open and full of space, with each instrument free-floating and unhurried, an elegant backdrop that honored her voice like the diamond it was. Hearing those songs, even now, is like a glimpse through a camera obscura—simple and otherworldly at once, a down-home and unpretentious songbook lavished with the utmost care and talent.

“Crazy” was about as far from “rootsy” as a country song could be in 1961. Only its lyrics bear a resemblance to Hank Williams; musically, it’s a web of jazz changes with a rollercoaster vocal melody, arranged like a lush cabaret performance. Not long before this, Harman contributed the classic snapping drum track to the Everlys’ “Cathy’s Clown,” and in 1964 he created the immortal beat behind Roy Orbison’s “Oh, Pretty Woman,” another rock staple. But “Crazy” is in its own category, with its own still-vexing atmosphere. Harman’s drumming is just as indelible here as in his louder performances. To play such a gentle, unobtrusive pattern, confident that it will carry music of this slow power and weight, is a form of musical genius. It reveals an expert, empathetic listener.

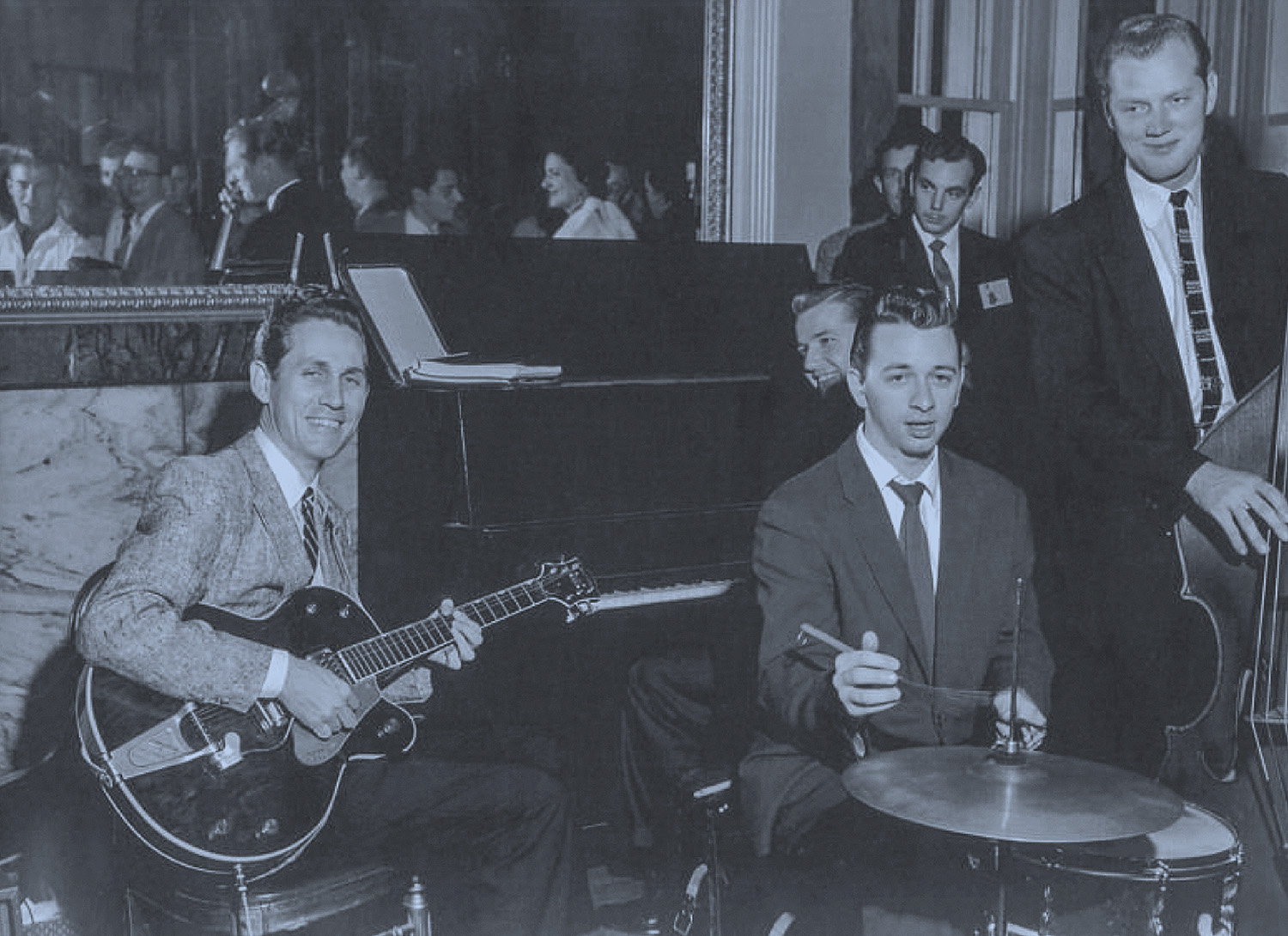

Promotional photograph of the Tunesmiths

“Cathy’s Clown” and “Oh, Pretty Woman” showed that Harman was becoming, in his words, “a little bit braver” behind the kit. But the Nashville producers, “they wanted it straight-ahead. A lot more limited.” In country, the drums were mere underlining. Virtuosic singers and string players still provided every necessary emotional shade or instrumental achievement in this music; drums just kept everything running on the same track, whether with an energetic train beat or the fragile, heavy sway of a heartbreak ballad.

That wasn’t a small assignment, especially not in the world that Atkins and Bradley built in the 1960s, when Buddy Harman was their first-call drummer. He was the most in-demand percussionist of the unofficially named Nashville A-Team, the rotating house band for the label studios on Music Row, and played an estimated eighteen thousand sessions for George Jones, Johnny Cash, Tammy Wynette, Roger Miller, Ray Price, Loretta Lynn, and just about every other major country star through the 1970s. Harman kept as busy as anyone in town, often playing four sessions a day for years.

A studio musician lives while the red light is on. Everything in their lives and their style is oriented toward doing exactly the right thing when the engineer points the finger through the console glass. And personal expression isn’t a high priority when a national corporation is paying by the hour. Your job is to do your job—well and quickly, then move on to the next one as soon as possible. Even though the A-Team was a shifting combination of the same players, the band had different guises when they played behind different singers. They knew how to switch from being “the Possum’s band” to “Loretta’s band,” and they knew how each of them sounded best. Harman was a master of country drumming’s very limited technical repertoire, and that was plenty. His brushwork in “Ring of Fire” is sprightly and springy, while his part on “Stand By Your Man” is far more dramatic, with greater dynamic range and even a deep bass drum.

That latter hit came in 1968, by which time the Nashville Sound was running headlong into contemporary fashion. “Stand By Your Man” was produced and co-written by Billy Sherrill, who would soon become the hottest producer in Music City. He borrowed the Nashville Sound’s most pop-friendly excesses (namely the strings) and added a little muscle. His signature works, like Charlie Rich’s 1973 Behind Closed Doors, or George Jones’s The Grand Tour from 1974, had the requisite Nashville stateliness but reflected the fact that viable country was now coming out of Bakersfield, L.A., even Austin. Harman, Jerry Carrigan, and Kenny Buttrey played regularly on Sherrill productions, and even sometimes used two sticks.

Even as players like Harman, Carrigan, and Buttrey revolutionized country behind the scenes, Nashville gatekeepers still denied the drums a part in the music’s public image. Back in 1935, Bob Wills was already a celebrity bandleader when he invited Smokey Dacus on board, and apparently the drummer was mystified: “What in the hell do you want with a drummer in a fiddle band?” he asked, and Wills replied, “I want to take your kind of music and my kind of music and put them together and make it swing.”

Western swing became its own phenomenon and Wills reigned as the Texas country king for decades, but his innovation—just one snare!—wasn’t welcomed by the ultra-conservative Nashville mainstream. In 1944, Wills was finally invited to the Grand Ole Opry but was told to put his drummer behind a curtain onstage—and even more hilariously, to not even mention the instrument on the air. When he gleefully defied both orders during his performance, the Texas Playboys were never asked back to country’s most hallowed stage.

It wasn’t only Wills, though. Drums were held behind the Opry curtain for decades, including when Buddy Harman became a regular performer in 1954. It wasn’t until 1974, when the Opry moved to its extravagant new Opryland venue, that a full drum set was allowed on stage and visible to all, and Buddy Harman was the most routine presence behind it every week for decades longer.

The Nashville drummers that emerged in Harman’s wake were used to playing a full kit from the start of their careers. Long gone were the days of single snares or literal whispers in the studio; Eddie Bayers Jr. and John “JR” Robinson had real backbeats and multiple crash cymbals. They made country sound appropriate for drum-heavy 1980s radio and the booming Opryland stage.

Country music is tradition but Nashville is commerce, and commerce eats tradition every time. By 2000, when Buddy Harman was seventy-two, he and other old-timers had become too old-fashioned for the Opry band. He survived the crossover of country and rock because he lived that crossover himself, but how can any 1950s beatmaker hope to survive in the age of “Man! I Feel Like a Woman”? Pop once meant a swinging snare pattern; now it meant drum programming and amplification. Garth Brooks and Faith Hill weren’t going to reach the back walls of arenas with brushes.

Photograph of Chet Atkins, Floyd Cramer, and Bob Moore. Courtesy Buddy Harman Jr.

Country strings are tremendously expressive; twang is a guitarist’s approximation of human speech. Bends and microtones on a pedal steel are like a trumpet growling from behind a plunger mute—an evocation of spoken drawls. Even in string bands and drum-free bluegrass combos, the mandolin and upright bass can approximate a backbeat well enough that the music is truly propulsive.

Actual drums are granted no such range. They deepen a country song’s charm but rarely define it. If a producer needs arena-sized volume, a Nashville drummer needs to supply that. Buddy Harman’s Opry exit wasn’t surprising—it was inevitable in a community that always follows the market. The surprise was his longevity during a time of huge Nashville change. His career is both vast and simple, almost a series of Zen koans: how to spend decades mastering restraint? To play so much music so unhurriedly, so consistently? To sublimate your own ego for the strict needs of your genre, especially after idolizing Buddy Rich and Gene Krupa?

For all his laid-back playing, Harman was a machine. “I worked around the clock,” he told an interviewer in 2003. “I came home one night and asked my wife, ‘Where are the kids?’ She said, ‘They grew up and left home.’” In his 2008 New York Times obituary, his daughter said he was playing drums in his sleep in his final days. He had a smile on his face and his hands were moving, an image that reminds me of John Coltrane supposedly practicing fingerings on a broom handle while grocery shopping, keeping a ceaseless silent connection to the muse.

Harman’s role was simpler, his revolution was tectonic. He slowly opened the music’s sound and intensity without ever threatening to distract from the stars on the track. He smuggled percussion into the country charts, then kept it there, almost in hiding, until his influence spread so far he could finally lead his peers out of literal anonymity. Buddy Harman entered country music as a novelty and when he left, drums were a necessity. He gave this music a heartbeat it didn’t know it needed.